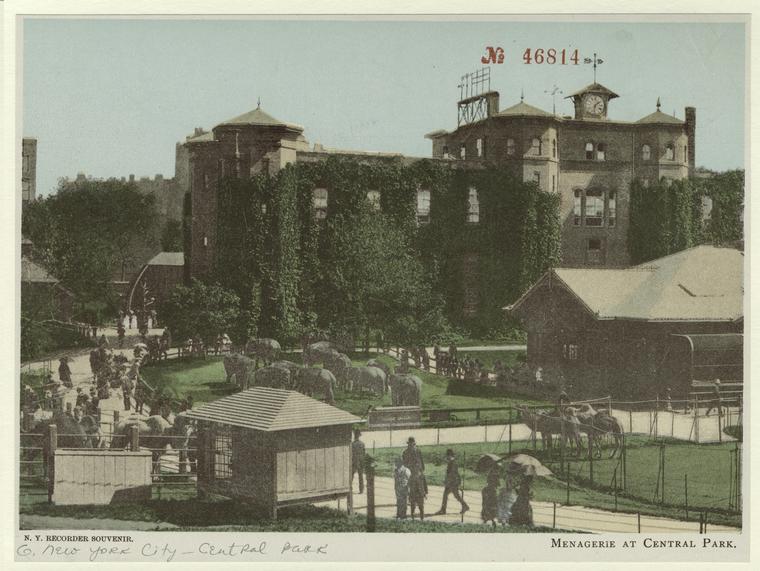

“Menagerie at Central Park.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1900–1909.

• The artificial nature of Frederick Law Olmsted: “Everything in Central Park is man-made; the same is true of most of Olmsted’s designs. They are not imitations of nature so much as idealizations, like the landscape paintings of the Hudson River School. Each Olmsted creation was the product of painstaking sleight of hand, requiring enormous amounts of labor and expense. In his notes on Central Park, Olmsted called for thinning forests, creating artificially winding and uneven paths, and clearing away ‘indifferent plants,’ ugly rocks, and inconvenient hillocks and depressions—all in order to ‘induce the formation…of natural landscape scenery.’ He complained to his superintendents when his parks appeared ‘too gardenlike’ and constantly demanded that they ‘be made more natural.’” (The Atlantic)

• Reshaping our understanding of landscape through balloon flight. (Public Domain Review)

• Inventing the American history play: “A notorious 1849 riot in New York pitted supporters of a distinguished British actor’s production of ‘Macbeth’ against a working-class American actor’s turn in the role—it was billed, in a contemporary pamphlet, as a clash of ‘the aristocracy against the people.’ A century later, Arthur Miller defended ‘Death of a Salesman’ with an essay in the Times, arguing that ‘the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were’ for Shakespeare. Within a few years, Joseph Papp began presenting Shakespeare’s plays in New York as a free, democratic birthright for all Americans.” (The New Yorker Page Turner)

• The Olympics: better in space? (Nautilus)

• The many and varied uses of electricity: “Electricity was about sex as well. In one popular demonstration, a young woman stood on a stool holding the chain from an electrical machine. As long as no one touched her all was fine, but when a gentleman was challenged to give her a kiss the sparks flew. Then there was medical entrepreneur James Graham’s Celestial Bed. In 1781, based at his Temple of Hymen on fashionable Pall Mall in London, Graham charged wealthy childless clients £50 a night to have sex in the electrified dome and forged a link between electricity, sex and fertility that would persist throughout the Victorian era.” (Aeon)

• The annotations of T.S. Eliot, by T.S. Eliot. (London Review of Books)