The Girl by the Window, by Edvard Munch, 1893. The Art Institute of Chicago, Searle Family Trust and Goldabelle McComb Finn endowments; Charles H. and Mary F.S. Worcester Collection.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.

Why study classic novels? An oft-repeated justification has been that reading literary fiction is a means of self-improvement that yields a more empathetic person, one who can relate to those unlike themselves. From its eighteenth-century debut, the literary form that came to be known as the novel was hailed—and sometimes castigated—for bringing into view the lives of the marginalized and lowly or the ordinary and obscure. Arguing for literature as a catalyst for personal growth has led some well-intentioned scholars of eighteenth-century and Romantic-era literature to invest their critical energies disproportionately in the segments of the Western literary legacy that promote democratic values as well as ideas such as the equality of persons. Certainly, humanitarian fiction—including Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740) and Clarissa (1747–48)—and “novelistic autobiographies”—such as Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative (1789)—reached a wide audience and altered popular understanding of what types of stories could be told. While a number of critics have questioned this approach by arguing that novel-induced empathy rarely translates into real-world altruistic action, they leave intact the undergirding premise that the lowly and marginalized are the rightful objects of empathy.

As the eighteenth century waned, the legal system was a target of complaint not only from those who had never enjoyed its shielding in the first place but also from members of society accustomed to protection by the law and dismayed by the prospect of its loss. Channeling these complaints, and downplaying or neglecting the problems identified by humanitarian fiction, a variety of conservative novels were composed to support the polar-opposite ideological objective: safeguarding an establishment whose legal perquisites were threatened, and sometimes felled, as those of lower status made their way up the rungs of the social ladder. Although conservative authors held complex and sometimes self-contradictory political views, they shared interests in defending the preeminence of the civil rights of the privileged and in advocating legal reforms designed to protect traditional social hierarchy.

If “liberalism itself is a fiction of harm” (as literary scholar Sandra Macpherson puts it), these authors fashioned fictions that used the rhetoric of liberalism to conservative advantage, presenting readers with the plight of impoverished or abandoned descendants of distinguished families brought low by the legal system. They cast the privileged as society’s most vulnerable. Although scholars today tend to associate appeals to sympathy with liberatory discourse of the period (such as the writings of protofeminist and Black Atlantic authors), conservative authors made their own claims on readers’ sympathy, intuitively understanding “this disposition of mankind, to go along with all the passions of the rich and powerful,” as Adam Smith stated in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). As did their humanitarian counterparts, these authors turned to the novel as a demotic discursive form to amplify their agenda and reach a popular audience beyond like-minded elites.

Humanitarian and conservative novels share at least two prominent elements. First, both categories of novel cast protagonists as victims of undeserved persecution and explicitly express antipathy toward the legal system. Yet humanitarian fictions such as William Godwin’s Caleb Williams (originally published in 1794) suggest that the institutions that shape social environments—rather than the individual people within them—are terminally damaged, casting aspersions on marriage, government, and the legal system. Conservative novels, by contrast, assert that such failed institutions can be rehabilitated and restored: devoted guardians step in to repair the damage wrought by cruel or absent fathers; kindly aristocrats rescue women from abusive husbands; ethical judges provide counterexamples to self-serving, corrupt magistrates; and laws preserve peace and order when properly enforced.

Second, both types of fiction foreground interactions among different classes that often relate to legal disputes. Some 1790s and early 1800s Jacobin fictions such as Mary Wollstonecraft’s The Wrongs of Woman; or, Maria (1798) model interclass sympathetic affinity, as when privileged Maria, on entering the asylum to which she has been lawfully relegated by her husband, is befriended by impoverished Jemima. In conservative novels, however, characters of lower status are commended for maintaining their place; these characters show loyalty to their betters and dedicate themselves complacently to physical and emotional toil. Subordinates who violate this norm—duplicitous servants and rebellious slaves—are reviled. Lawyers and judicial authorities who aspire to improve their station and seek to marry into landed families are cast as malevolent usurpers.

While conservatism is associated with the powers that be, or the establishment, writers who held conservative views frequently employed an accusatory rhetoric of unjust deprivation and loss resembling that voiced by their humanitarian counterparts. Because claims involving legal standing and status were (and are) construed as more affecting and morally compelling when victimhood is invoked, it is essential to understand the narrative mechanisms by which particular legal claims were cast as especially poignant and deserving of redress during a foundational historical era.

Although sometimes derided in its day as mere entertainment, popular literature such as the novel supplements the historical record. Court records and legal treatises do not record certain pivotal but private interactions, such as consultations between lawyers and indigent clients. To a greater degree than other literary forms, novels render visible legal communication that would otherwise remain invisible to the general public and demonstrate how such encounters can bolster or diminish a person’s sense of belonging in the legal sphere. As legal historians have shown, even as lawyers took significantly more prominent roles in criminal trials near the end of the long eighteenth century, other legal vistas were extended in realms far afield from the public spectacle of criminal trials—for example, the behind-the-scenes business of conveyancing, a branch of law that particularly interested wealthy and aristocratic clients.

Because the privileged were willing to use any means necessary to retain their power, they exerted their influence wherever they could. When legal institutions fail them, the powerful resort to entirely extralegal settings—where their influence remains intact—to challenge or renegotiate undesirable legal outcomes: private asylums, rural cottages, smuggler’s outposts, and hidden repositories in plantation mansions.

The standard history of the eighteenth-century novel casts it as a dismantler of traditional hierarchies and associates it with the emergence of the liberal subject. This understanding of the novel’s legal and political reach has encompassed the emerging discourse of human rights: a number of critical studies posit the novel’s implicit endorsement of human dignity even in the absence of actual legal agency. By bringing to light the interiority of its subjects, so the logic goes, the novel as a literary form created pressure for institutions to validate this worth through the conferral of legal roles and access hitherto withheld.

It can be difficult to distinguish conservative novels from humanitarian novels based on register of language alone because conservative novels are not composed in the haughty, formal, inaccessible register of legal treatises from the period—and this is a feature, not a bug, for the purposes of the conservative novel’s mission. Conservative and humanitarian novels alike castigate the opaque language of law and the corruption and arrogance of legal professionals. In my reading, the conservative novel, with its demotic articulation of challenging legal concepts, operated as a Trojan horse: conservative novels were presented to readers as mere entertainment but in fact harbored nostalgic fantasies of a continuation of rigid social hierarchy. Middle-class readers were pressed into the position of hoping that a privileged scion would regain his family’s estate or feeling indignation on behalf of an aristocrat compelled to face plaintiffs in court instead of settling matters through combat.

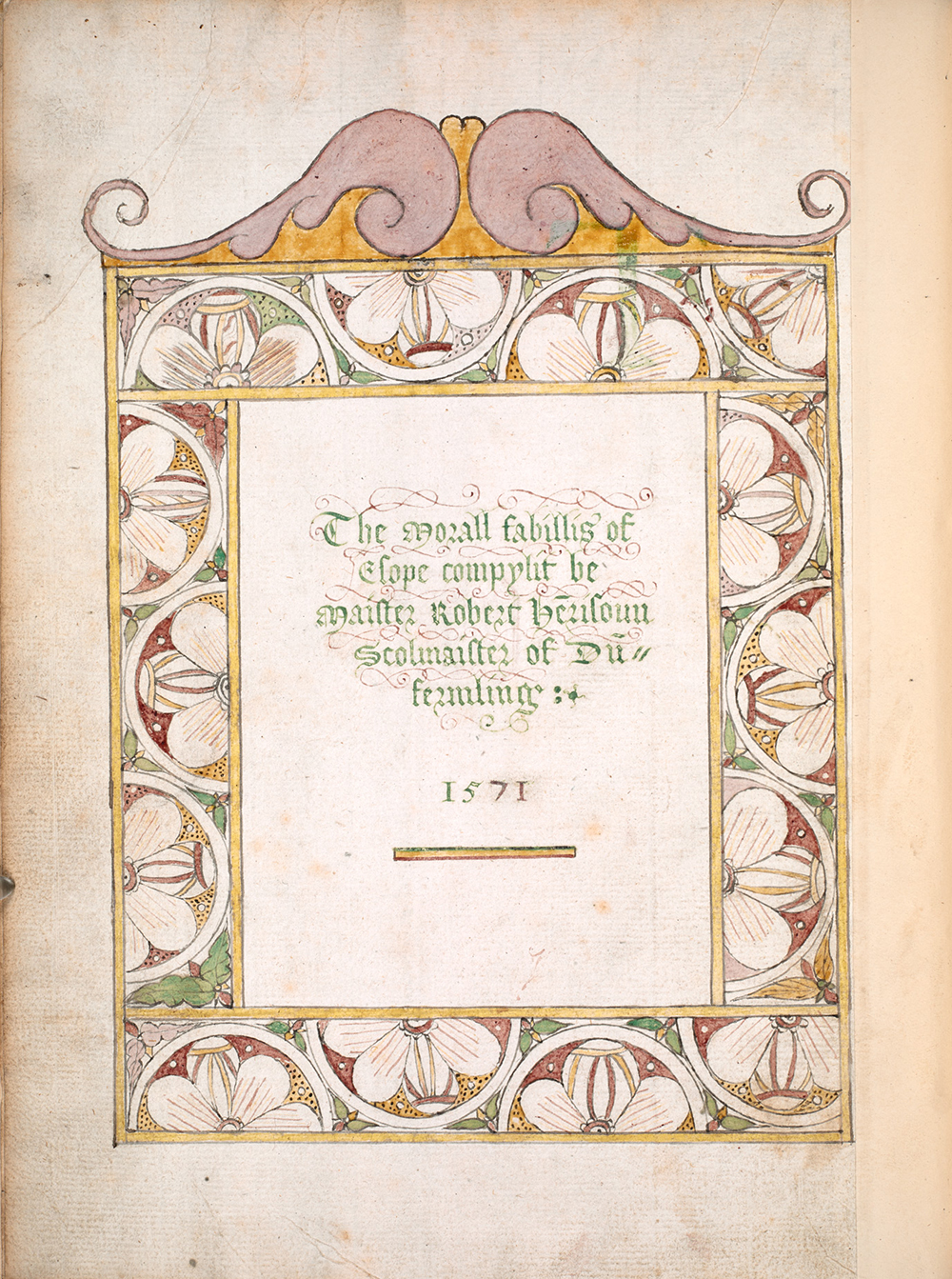

Despite their efforts to preserve the status quo, some of the most provocative—and, at times, unintentionally forward-thinking—visions of the expansion of legal agency can be found in the unlikely vehicle of the conservative novel. Some conservative novels unwittingly aided certain humanitarian causes, albeit in an incrementalist manner: in portraying legal institutions as mishandling cases involving the privileged, the novels of Tobias Smollett and Charlotte Smith supported the carving out of exceptions that fortified and expanded the rights of certain groups—such as women of the gentry or wealthy Jewish immigrants—whose marginality in some aspects was tempered by privilege in others. More audaciously, the works of Walter Scott and proslavery novelists reveal that in order to disparage marginalized figures as unsuited for key roles—impoverished folk as legal clients, animals as plaintiffs, slaves as witnesses—conservative novelists needed to entertain the prospect of such eventualities in the first place. In novels prior to 1750, by comparison, the primary legal role allocated to underclass characters had typically been that of a defendant contesting criminal charges. In another point of contrast, depictions of animals in legal roles in late medieval texts are typically composed as allegorical. Scottish poet Robert Henryson’s Morall Fabillis (Moral Fables, c. 1480s) features a sheep that loses a lawsuit to a dog, owing to a corrupt ruling by a wolf judge, and must submit to being shorn; the sheep is explicitly identified as a symbol of poor commoners: “This selie scheip may present the figure / Of pure commounis.” Centuries later, in the Walter Scott novel Redgauntlet, by contrast, a farmer’s guest’s brief but potent suggestion—that livestock might object to being sentenced to bodily harm—is at once playful and reflective of contemporaneous debates over animal rights. In the course of implementing their literary strategy intended to safeguard privilege, conservative novelists inadvertently envisioned a more radical legal ecosystem than even their most progressive contemporaries could conceive.

In conservative novels of centuries past, I see a prototypical version of an additive approach to identity: just as intersectional theorists see qualities such as indigeneity and poverty compounding each other to exacerbate an individual’s exposure to the regulatory force of law, eighteenth-century and Romantic-era conservative novelists figured certain traits associated with disadvantage—such as female gender and downward mobility—as attributes that offset advantage (such as noble heritage or wealthy connections). Privileged protagonists could thus be cast credibly as dispossessed victims.

To understand how aggrieved victimhood became a primary index of legal merit in the popular imaginary of the West, we need a different history of the novel.

Excerpted from Defending Privilege: Rights, Status, and Legal Peril in the British Novel by Nicole Mansfield Wright. Copyright © 2020 Johns Hopkins University Press, the publisher. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.