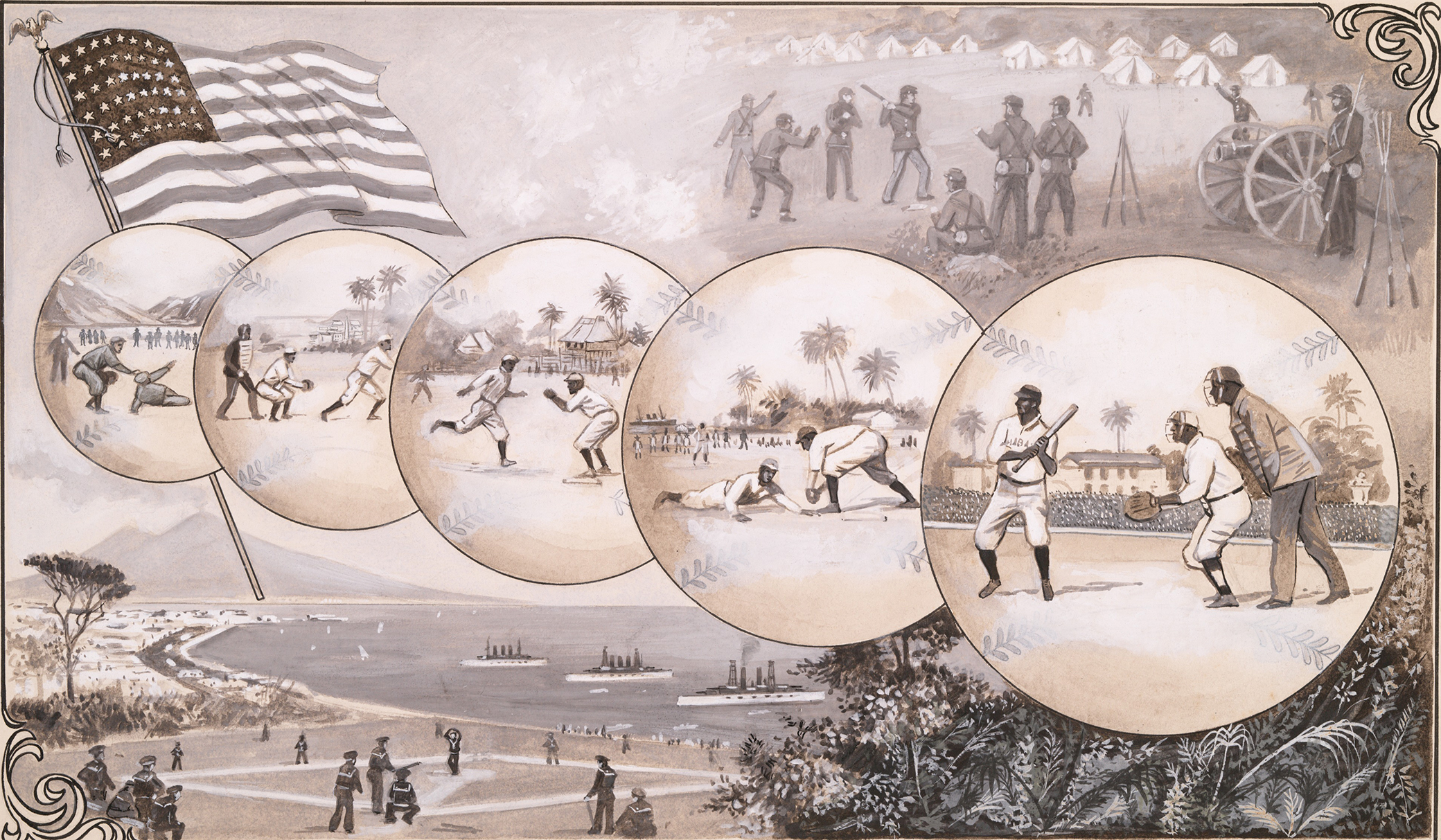

Baseball Follows the Flag. The New York Public Library, A.G. Spalding Baseball Collection.

The role of the Civil War in spreading baseball across the nation, far beyond the northeastern states where the game began, is the first example of baseball’s complicated relationship with America’s iconic image of itself. Union soldiers from the Middle West, many of whom had never been exposed to baseball before serving in the army, learned the game from their contact, during the prolonged waiting times in encampments between battles, with soldiers from the Northeast who already played and understood the prematurely named national pastime. Some Union officers actually sent reports to their superiors recommending that baseball be promoted in encampments in order to keep the minds of soldiers off the war. Baseball equipment was a problem. The standard “ball” was a walnut wrapped with yarn until a piece of horsehide would fit around it tightly. Branches of oak trees were cut down and carved into bats. Special baseball gloves did not yet exist. After the war, surviving Union soldiers brought baseball back to their communities and taught it to their children, laying the basis for the national game as an ordinary person’s recreation as well as a professional sport. In the decade after the Civil War, baseball in the North spread from “the region of the Manhattanese” to the northern plains states, where the summer playing season was short and the first snowflakes might appear as early as September.

The Civil War also spread the game to the South, but southerners learned how to play in prison camps—not only if they were imprisoned in the North, but from Union soldiers imprisoned within the Confederacy. Treatment of prisoners in camps became more brutal after 1863, when all prisoner exchanges were suspended by the Union because the Confederate Army treated captured black soldiers not as prisoners of war but as the property of their former masters—even if the master was unknown or nonexistent. After President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the Union Army stepped up recruitment of black soldiers. From the Confederacy’s viewpoint, all black soldiers were former slaves—whether or not they had actually lived in the South or been slaves under pre–Civil War laws. A black soldier captured by the Confederate Army had almost no chance of coming home alive. In the days when exchanges were still possible, however, baseball games were played in both northern and southern prison camps.

It is one of the ironies of baseball history that the game truly became America’s “national pastime” only after a war in which more than 620,000 soldiers died. The unfinished business of that war—America’s resistance to racial equality in the North and South—meant that baseball would develop, on both a semiprofessional and a professional basis—as a largely segregated national pastime. This development was not inevitable—not, at least, until the end of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. There were a few nineteenth-century blacks—their names unknown to almost everyone today except scholars of baseball—who played for professional teams in the first two decades after the Civil War. Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker caught for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the then–major league American Association in the early 1880s, and his brother Welday also played a few games in the outfield for the team. Fleet Walker attracted the racial animus—actually, “hatred” is the correct word—of Adrian “Cap” Anson, an enormously influential figure in the history of baseball who played twenty-seven seasons at first base, mainly for the Chicago White Stockings (who eventually became the Cubs, not the White Sox). Born in Marshalltown, Iowa, Anson became the first player to reach three thousand hits—and he was also an ardent segregationist. Anson, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1939, refused to play against a team with a black man on the field. In 1884, according to various scholars, the Chicago team asked for assurances that Fleet Walker would not be on the field at an exhibition game with Toledo.

This evolved into the infamous “gentlemen’s agreement” that prevented blacks from playing in the major leagues until 1947. Some gentlemen. In the official exhibition on Anson in Cooperstown, former Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen described Anson thus: “Sturdy, blunt, and honest…the captain who was always kicking at decisions, the symbol of all that was strong and good in baseball.” This is indeed a description worthy of inclusion in the Baseball Hall of Shame. Anson wasn’t the only villain in the so-called gentlemen’s agreement. Many of Walker’s own teammates shunned him. According to one baseball historian, Toledo pitcher Tony Mullane would “intentionally throw the ball in the dirt, trying to injure his own battery mate.”

In the decades after the institutionalization of segregation in professional baseball, blacks could and did watch white baseball—usually from separate blocs of seats—and whites could and did watch black baseball. But the playing field itself never offered the possibility of equality, any more than a great many trains, hotels, and restaurants did. Whatever patriotic associations were fostered by and embedded in baseball, turning a blind eye to segregation was part of the deal. In his essay “My Baseball Years,” Philip Roth writes about his own feelings of patriotism when he attended minor league games in Newark during the Second World War.

It would have seemed to me an emotional thrill forsaken if, before the Newark Bears took on the hated enemy from across the marshes, the Jersey City Giants, we hadn’t first to rise to our feet (my father, my brother, and I—along with our inimical countrymen, the city’s Germans, Irish, Poles, and, out in the Africa of the bleachers, Newark’s Negroes) to celebrate the America that had given to this unharmonious mob a game so grand and beautiful.

The Africa of the bleachers. Much has been written about the importance of baseball in the Americanization of immigrants and their children from the early 1900s through the Second World War. Not least among the factors contributing to Americanization was the fact that by the time Roth was a young fan, the sons of first-generation immigrants had established themselves as stars of the game. Among the most prominent were Lou Gehrig, whose background as the son of German immigrants helped make an enthusiastic fan out of my grandmother; Hank Greenberg, born on the Lower East Side to Romanian Jewish immigrants; and Joe DiMaggio, the eighth of nine children born to Sicilian immigrant parents. But black Americans, whose families had been in the United States for hundreds of years, were relegated not only to the Africa of the bleachers in professional parks but to the Africa of the Negro Leagues. It is not an exaggeration to say that the desegregation of baseball in 1947 was as much a part of the unfinished business of the Civil War as the desegregation of the military was in 1948. But it had taken another war and another eighty-plus years to move both baseball and the military toward some semblance of justice—another demonstration of why baseball’s identification with American values matters and why those values continue to demand close scrutiny. Yet who could have imagined in 1941 that an unknown Jack Roosevelt Robinson, who was assigned to a segregated Army unit (there were no others, of course) and narrowly survived an attempt to court-martial him for refusing to move to the back of a military bus, would break the color barrier in baseball only two years after the war’s end. Baseball desegregated, with difficulty and dissension, not because it was the right thing to do (although some exceptional men, like Bill Veeck and Branch Rickey, recognized that it was) but because MLB needed the talent of great black players. Desegregation was based on baseball’s pragmatic needs, not idealism. But that is not an indictment of the game. One can only wish that the nation’s finest educational institutions and most successful businesses had come to the same realization as early as 1947.

In no historical period had baseball’s connection with American identity been more complicated than during the Second World War. More than five hundred major league players served in the military. They included many stars of the game—DiMaggio, Greenberg, Ralph Kiner, Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Bob Feller, to name only a few. All returned home, resumed their careers, and eventually wound up in the Hall of Fame, but devotees of statistics still love to figure out how much better the lifetime records would have been had the athletes not lost several prime playing years to war.

Baseball was played by the troops wherever fields could be carved out adjacent to military encampments. There is even an iconic photograph—reminiscent of a Civil War prison lithograph depicting a ball game—showing marines in the Solomon Islands studying their position on the map while also poring over baseball scores. The photo was published in the Marine Corps’ Guadalcanal Gazette.

Japan as an enemy, however, posed something of a problem for the baseball establishment, which included the sporting press. The nation that attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor had embraced baseball since the 1870s. The game was imported by the American missionary Horace Wilson, who taught at an institution of higher education that is now Tokyo University. Baseball became so popular, and so respected, in Japan that the game received a Japanese name—yakyu. All other sports that trace their origins to foreign countries—such as football, soccer, tennis, basketball, and golf—are known only by their foreign names in Japan.

In 1934 a team of American all-stars, headed by Babe Ruth, toured Japan to enormous popular acclaim and competed with the Nippon all-stars. Jimmie Foxx, the second American player to hit more than five hundred home runs (after Ruth), was also on the tour, and he captured the camaraderie and excitement in eight-millimeter, black-and-white film, now digitized and stored in the Hall of Fame. Japan—the only nation in Asia or Europe to fall in love with the American national pastime—was now our mortal enemy. What did this mean about the sanctified American values supposedly embodied by baseball? As one historian of the military and baseball puts it, “If baseball embodied those values that made America great, such as fair play, hustle, and teamwork, did Japan’s love of the game mean that the Japanese exhibited these qualities as well?”

Just eleven days after Pearl Harbor, J.G. Taylor Spink, editor of the Sporting News, addressed the issue in an editorial. Baseball, he explained (in a burst of venom that did not do justice to Horace Wilson or his nineteenth-century Japanese students) was not a recent phenomenon in Japan.

It dates back some 70 years, not so long after our American Civil War. It was introduced by American missionaries, who wanted to wean their boy pupils away from such native sports as the stupid Japanese wrestling, fencing with crude broadswords, and jiu-jitsu. Having a natural catlike agility, the Japanese took naturally to the diamond pastime. They became first-class fielders and made some progress in pitching, but because of their smallness of stature, they remained feeble hitters. In their games with visiting American teams, it was always a sore spot with this cocky race that their batsmen were so outclasssed by the stronger, more powerful American sluggers. For, despite the brusqueness and braggadocio of the militarists, Japanese cockiness hid a natural inferiority complex.

Spink concluded that Japan was never truly “converted” to baseball, despite its enormous popularity before the war. “They may have acquired a little skill at the game,” he told his readers, “but the soul of our National Game never touched them. No nation which has had as intimate contact with baseball as the Japanese could have committed the vicious, infamous deed of the early morning of December 7, 1941, if the spirit of the game had ever penetrated their yellow hides.”

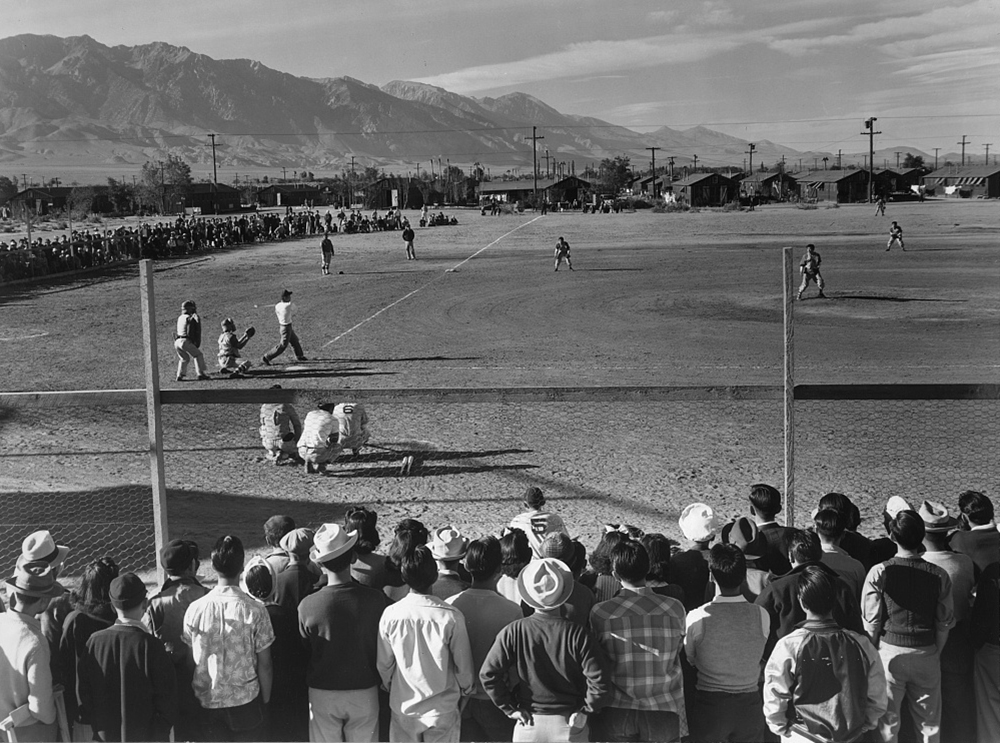

Take that, you slant-eyes! Yes, the Japanese, with their feline agility, might have learned how to turn a nifty double play, but they could never really comprehend or partake of the goodness and purity of America’s game. Spink’s rationale certainly did embody the American values that led to the imprisonment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during the war. It is to be hoped that when Ichiro Suzuki becomes the first Japanese-born and Japanese-bred player elevated to the baseball Hall of Fame, a copy of this editorial will be prominently displayed in the exhibit dedicated to him.

Excerpted from Why Baseball Matters by Susan Jacoby. Copyright © 2018 by Susan Jacoby. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.