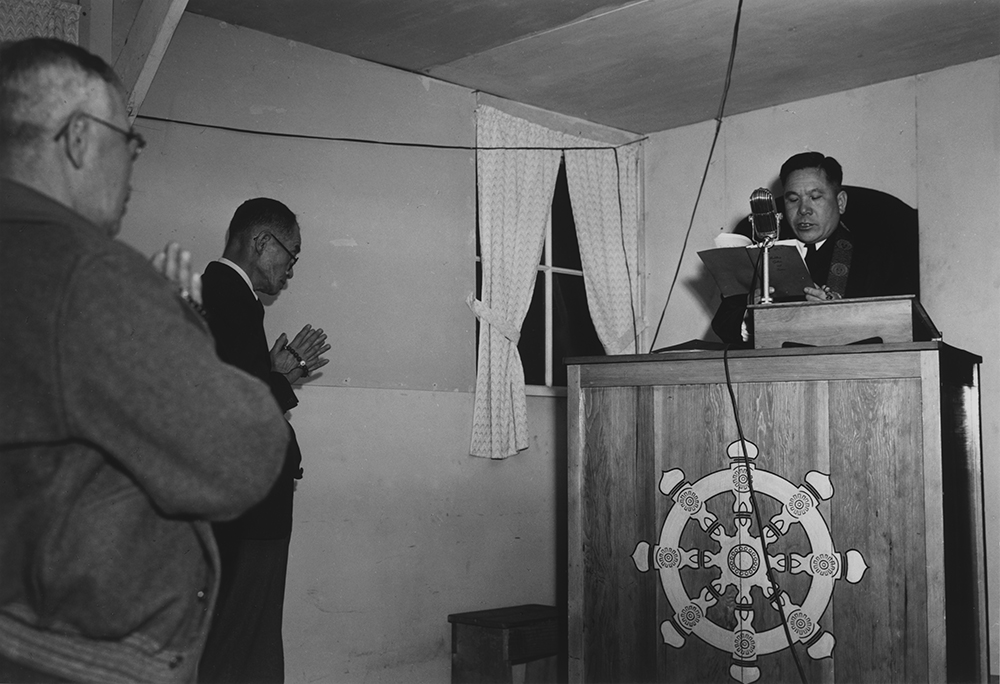

People leaving a Buddhist church in winter at Manzanar Relocation Center, California, 1943. Photograph by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Despite being targeted by government authorities, most Buddhists did not allow fear to diminish their faith behind barbed-wire fences during World War II. In the high-security camps run by the U.S. Army and the Department of Justice, the incarcerated Buddhist priests were predominantly issei men who had migrated from Japan for the explicit purpose of bringing the Buddhist religion to the Americas. These priests’ outlook, values, and practices were unlikely to waver. They believed that Buddhism had something to offer the American religious landscape.

Imprisonment became an opportunity to discover freedom—a liberation that the Buddha himself attained only after embarking on a spiritual journey filled with many obstacles and hardships. That journey began when he let go of his comfortable life as a prince in the royal palace of the Shakya clan into which he was born, an acknowledgment that unease and suffering were not only part of being alive, but essential to discovering one’s own nature and the world’s.

In Buddhism, the practice of delving into the depths of this world so as to transcend it is sometimes symbolized by the image of a beautiful lotus flower emerging out of muddy waters. The lotus flower represents enlightenment and in sculptural traditions is the seat upon which the Buddha is centered. Muddy water represents delusion and greed, or anything that hinders enlightenment and causes suffering. While some traditions of Buddhism center on the need to transcend the muddy water to attain a state of enlightenment, most Japanese Buddhist traditions emphasize that for the lotus flower to exist, the nutrients from the muddy waters are essential. It is a metaphor that emphasizes how the karmic obstacles of this world are interconnected with liberation and enlightenment.

For the interned Buddhist priests, incarceration often served as muddy water.

At Camp McCoy in Wisconsin, Bishop Kyokujō Kubokawa of the Jōdo sect—a priest who had been arrested in Hawai‘i in his Buddhist robes—officiated at the first Buddha birthday ceremony. With these robes, he had arrived in the internment camp as the only priest with the appropriate attire to officiate at such an auspicious occasion. One priest wrote that he had only a single pair of underwear, a pair of pants he’d been unable to wash, and a belt made of rope. To the disheveled men, Bishop Kubokawa delivered his sermon. “Your participation in those filthy clothes can be likened to the Buddha’s teaching of the lotus blooming in the mud,” he said. In these muddiest of waters, the men found ways to embrace all manner of karmic hindrances to realize the lotus mind of freedom, wisdom, and compassion. At another Buddha’s birthday celebration in Fort Lincoln Internment Camp (North Dakota), Rev. Bunyū Fujimura from the Salinas Buddhist Temple noted how the group managed to improvise without the normal items typically employed on the auspicious day:

We did not, of course, have a single religious implement to use for Buddhist services. We did not have a tanjobutsu [Baby Buddha statue], butsu-gu [Buddhist ritual tools], flowers, incense, or any of the implements used in Hanamatsuri [Buddha’s birthday] celebration. Fortunately, we were with many people who were clever with their hands. Arthur Yamabe “borrowed” a carrot from the kitchen and carved a splendid image of the Buddha.

The ritual to mark the birth of the religion would normally have involved the ceremonial pouring of sweet tea on a statue of the newborn Buddha. Without such items, the Buddhist priests imaginatively re-created the ritual for themselves collecting rationed sugar from other internees, stirring the sugar into coffee to concoct an American approximation of the traditional sweet tea, and pouring it over the carved carrot Buddha. Making do was, of course, part of the Buddhist tradition. Throughout Buddhist teachings, there are examples of people using whatever ingredients they could assemble.

Carrots were available. Rev. Rien Takahashi also used one to carve a Buddha for the founder’s birthday ceremony several days later at Camp McCoy, where many Buddhist priests from the Hawaiian Islands were initially incarcerated. In that camp, run by the army from March to May 1942, priests surrounded the carrot Buddha with “a cherry blossom flower arrangement” crafted by a Nishi Hongwanji priest using beet-dyed toilet paper, while a Jōdo sect priest officiated the intersectarian birthday ceremony at an altar created by transforming bread wrapping paper and labels from canned goods.

Describing the arrival of 415 Japanese at Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, on February 9, 1942, the Bismarck Tribune reported that “the little yellow men scrambled out of the coaches twenty-five at a time, were put in guarded trucks, and rushed out to the internment camp.”

In that same month at Fort Lincoln, one of the interned Japanese died of a heart attack. In a display of grief rare among Japanese men, his fellow internees “wept openly” at the funeral. Camp rules permitted only two persons to accompany the body out of the barbed-wire compound to Bismarck’s crematorium. Rev. Issei Matsuura, of the Guadalupe Buddhist Temple, volunteered to go. The town’s mortician later recalled his reaction to hearing the priest recite Buddhist sutras at the crematorium:

“What religion is this? This was my first Japanese funeral.” Responding to the mortician’s curiosity, Rev. Matsuura soon became engrossed in a conversation with him and an armed guard about salvation in Buddhist teachings, and the teaching that beings, including prisoners and guards, were all ultimately Buddhas. The men shook hands at the edge of the barbed-wire fence and expressed hope that they might meet again. Such moments were rare, and they stood out for Buddhists in their difficult circumstances.

On one of the many transfers between camps, on July 27, 1942, 148 Japanese were moved from Fort Lincoln to the Lordsburg Internment Camp in New Mexico. After disembarking at the Ulmoris Siding train station, the men were marched two miles through the desert to the camp. Two of the elderly men, Toshiro Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were in poor health and could not keep up with the main group. Along the road to the camp, Private First Class Clarence A. Burleson shot and killed them. According to the official government inquiry that followed, Burleson shot them because they had made a “break and started running” toward the reservation boundary. The other internees strongly doubted that account. Kobata had been quite frail due to long-term tuberculosis, and Isomura had suffered a spinal injury that made it difficult for him to walk, let alone run. The army refused to allow Japanese doctors in the group to perform autopsies.

The authorities also refused to allow a Buddhist funeral for the two men. In protest, the Buddhists in the camp refused orders to assemble at 4 pm the day after the shooting, stating that they would “pay their respects in their own barracks.” After the Japanese complained to the Spanish consul, who was an international monitor charged with overseeing the treatment of Japanese internees, the army permitted a small funeral, limited to forty people, three weeks later. Among those who planned the belated funeral were seven Buddhist priests. Rev. Tana, in his diary entry from the day, wrote about the service:

For flowers, we collected the artificial flowers that people all over the camp had made. Here in the middle of the desert, there are no live flowers except sagebrush. So, we took the wonderfully colored paper flowers, incense, and candles to offer to the two deceased men who have no proper gravestone. Given that we were able to gather in front of their corpses, it would be a shame not to perform a funeral service on behalf of the entire camp. We let everyone know about our funeral plans and we recited the Shōshinge. It was literally a funeral in the midst of the wild.

Priests continued their Buddhist practice by making do in a variety of ways. The Sōtō Zen priest Kōetsu Morita, from Hawai‘i’s Waiahole Tōmonji Temple, maintained a regular Zen meditation practice from 5 am to 6 am and from 9 pm to 10 pm—just before the military’s morning wake-up call and just after lights were ordered out. He used his prison-issued blanket as a zafu (meditation cushion), while he meditated and chanted sutras silently. Even some of the younger and not particularly religious men noticed this and one of them offered to make a statue. Rev. Morita recalled that one of them “went to the boiler room, carrying the steel pieces which he had picked up at the dump. There he forged those pieces into five or six chisels. At the time, I doubted a mere mason could carve a statue of a Buddha. Not long after, he brought over a piece of wood and began to carve steadily in the center of the barrack. In a few days, it began to take the shape of a standing Buddha with a halo.” The statue ended up as a beautiful, eleven-headed Kannon bodhisattva. Morita was so pleased that he invited the eight Sōtō Zen priests in the camp to hold a dedication ceremony for the new statue. He wanted to involve the younger men and thank them for their efforts, so he “purchased thirty bottles of beer at ten cents apiece, which made the young men very happy. They were also moved by the chanting of sutras, which they had not heard in many years since leaving Japan.”

Rev. Seytsū Takahashi, who was interned at Camp Livingston, adapted his Buddhist practices of meditation and sutra copying to the camp in the swamps of Louisiana. In a letter he sent to the caretaker of his temple in Los Angeles, Takahashi noted his sense of connection to others in Buddhist history who had transmitted the religion while overcoming various obstacles. He wrote:

I have thought that this lengthy internment life has been provided to me by Heaven and the Buddhas as an opportunity for years or months of Buddhist practice. I return to the quiet and supreme life of walking alongside Kōbō Daishi. As if trying to practice meditation under the moonlit pine, I have been viewing the guard’s searchlights as the Buddha’s sacred light and have been practicing Kōmyō meditation together with [Kōbō Daishi]. Making the heart-moon [mind-enlightenment] appear, longing after the form of Shakyamuni Buddha, and copying sutras each day has brought delight in the deep Dharmic teachings, which is happiness beyond measure. Further, I have come to appreciate the extreme efforts of those who brought the Buddha Dharma from India to China, and from China to Japan. I am indebted to the connection I had to the place where our founder practiced in Tosa Domain’s Murotosaki and I vow as my own practice because of this karmic connection, to recite the Buddha’s and bodhisattvas’s mantra 2 million times. I wish only to live in this great vow. I believe it is possible to achieve world peace through this practice that benefits oneself as well as others. Further, I pray for the safety and peace of mind and long life of all of the Daishi (Shingon) followers living here in America.

Takahashi recorded in his memoir how he used the extreme heat of the Louisiana summer to immerse himself more deeply in Buddhism, especially in classic teachings about employing karmic hindrances to attain liberation. In his first attempts at the traditional practice of shakyō (Buddhist sutra copying), he had found the task impossible. The swampy heat inside the barracks caused his sweat to drip onto the paper as he tried to copy Buddhist scriptures using the traditional calligraphic style. Using a handkerchief to lock his elbows into a position that prevented the sweat from dropping onto the paper, Takahashi managed to perfect the writing of the sacred script despite the awkward posture.

The copying of a Buddhist sutra in swampy Louisiana was yet another example of Buddhists practicing their faith in a moment of dislocation. In the movement of the Buddhist tradition from one cultural environment to another, this act of reiterating the teachings of the Buddha, however hostile the situation, was a way to maintain one’s traditions and simultaneously to inscribe one’s faith onto a new landscape.

Excerpted from American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War by Duncan Ryūken Williams, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.