Storage jar, Italian, c. 1500. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1946.

In 1524 Pope Clement VII ordered a test of an antidote oil created by surgeon Gregorio Caravita. A test subject took a dose of poison in front of a small crowd of invited personages. In both of the antidote’s two trials, apothecaries provided the poison—a good quantity of a deadly aconite called napellus in the first test, arsenic in the second. Although a pharmacist was present, the papal physician, Paolo Giovio, oversaw the trial. Pope Clement commanded that the antidote be tried on “condemned bodies, faithfully and diligently, for the benefit of the public.”

The use of condemned criminals as medical test subjects was new. We are lucky to have a firsthand account of the test of Caravita’s oil from the point of view of the testers: the pamphlet put out in Pope Clement’s name and written by Giovio, the pharmacist Tomasso Bigliotti, and the senator Pietro Borghese. This document, which they called a Testimonium (testimony) of the “true and admirable virtues” of the oil, allowed the testers to shape the narrative as they saw fit.

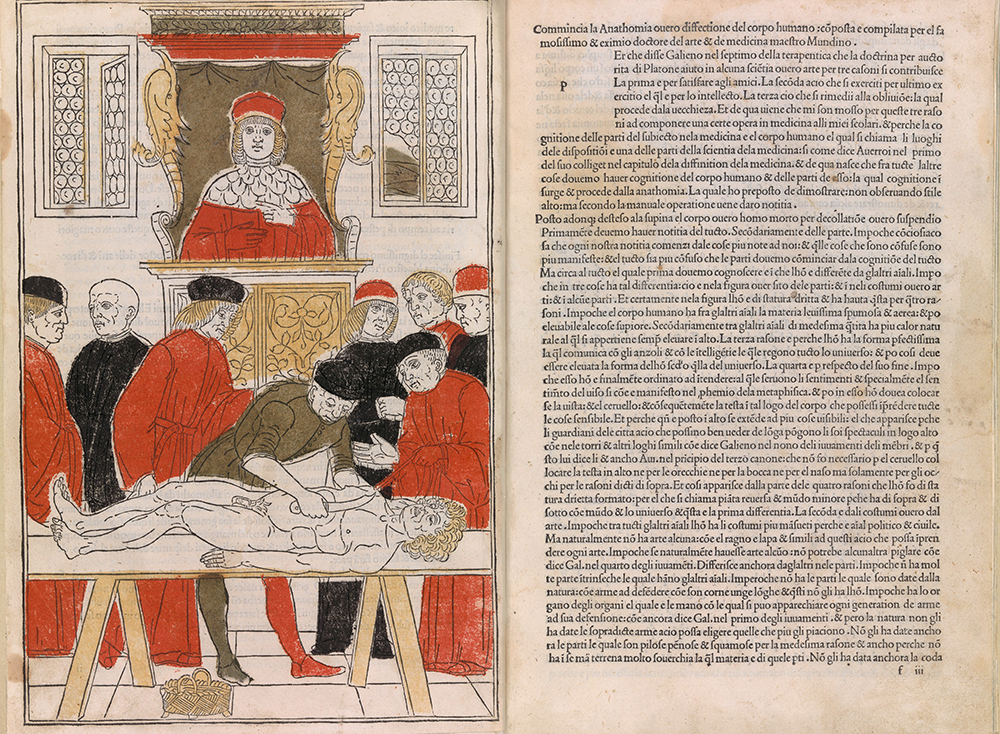

In 1502 Alessandro Benedetti (d. 1512), a humanist physician in Verona, published the first major Renaissance treatise on anatomy. It began with a full-throated defense of human dissection, especially for its potential to “help the living.” Benedetti went to some lengths to portray public dissection as an acceptable practice, both religiously and culturally. He noted first that “pontifical regulations” had long permitted the dissection of cadavers: “otherwise it would be regarded as most execrable and abominable or irreligious.” Benedetti thus emphasized the church’s endorsement of human dissection. At the same time, he clearly realized the practice was not as unproblematic as he claimed, as he also noted that “ritual purifications of the physicians’ souls take place” following dissections, in which they “propitiate their offense with prayers.” After alleviating all potential religious concerns, Benedetti explained why cultural discomfort was also unnecessary. He assured the reader that physicians used only cadavers of “unknown and ignoble” criminals “from distant regions” who had no family nearby. Their corpses thus could be used “without injury to neighbors and relatives.” With these careful measures in place, he implied, dissection was entirely unproblematic.

Benedetti left his readers with the sense that in the eyes of both medical and religious authorities, the handling of condemned criminals before death was less fraught than anatomizing the dead body. Criminals facing execution, he claimed, “have sometimes asked to be handed over to the colleges of physicians rather than to be killed by the hand of the public executioner,” with the understanding that they would be dissected afterward. He added, “cadavers of this kind cannot be obtained except by papal consent.” He made no other comment on the subject, leaving the impression that this unusual situation was not particularly problematic for the physician involved, as long as proper consent was obtained. Benedetti’s statement raises two tantalizing possibilities: first, that physicians sometimes had a direct hand in the death of criminals slated for dissection, and second, that popes would have known about—indeed, approved—these instances.

Whether or not such executions ever occurred is unclear, although there is a hint from later decades. Sometime in the 1540s or 1550s, the esteemed anatomist Gabriele Falloppio (1523–1562) described a test he had conducted on a condemned criminal granted to him by Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici. Duke Cosimo gave him the convict with the understanding that Falloppio could kill the man as he wished and dissect the body afterward. Falloppio decided to experiment with fatal doses of opium, a substance often described as a poison in the scholarly literature.

The prisoner survived the first test and asked for the dose to be doubled on the second attempt, on the assumption that he would go free if he survived, which he did not. Falloppio made no mention of papal sanction, but he also gave no indication that the event was unusual or untoward. This kind of private execution was almost certainly a rare practice, and this particular instance occurred long after the trial of Caravita’s oil—but if executing a prisoner via private experimentation was possible, the leap to experimenting with antidotes was not far.

By the time of Clement VII’s papacy, the Roman medical college was conducting an ever-increasing number of dissections, with full papal sanction. Anatomical practices also helped alert Pope Clement to the dire threat of poison. From the early sixteenth century, autopsies were conducted regularly on deceased popes, especially those who expired in circumstances that smacked of poisoning. One such case occurred at the death of Pope Leo X, who died suddenly, following a brief illness, on December 1, 1521. As reported by the pontiff’s master of ceremonies, Paride de Grassi, “the pope’s body was opened, and his heart and spleen were found to be corroded and the spleen similarly partially cauterized, which the surgeons and physicians viewed with amazement.” The assembled medical experts declared “for certain” that the pope had been poisoned. The pontiff’s cupbearer was arrested and examined but found innocent, and the case ended inconclusively.

This event took place only two years before Clement assumed the pontificate, and Leo was Clement’s first cousin and close friend, both from the powerful Medici family of Florence. Partisans of Leo’s immediate successor, the Dutch pope Adrian VI, similarly raised concerns about poison when he died only a year into his controversy-ridden papacy. Adrian’s body showed no suspicious signs, but the concerns about poison certainly would have reached Clement’s ears.

Poison was in the air in 1520s Rome, both figuratively and literally. Plague, the disease most connected to poison, struck the city in 1522, in the first summer of Pope Adrian VI’s pontificate. By early September, plague was raging in all quarters of Rome, and Pope Adrian’s curia were counseling him to leave the city. The pope refused. By December, finally, the brunt of the epidemic had passed and the city slowly began to recover. In August 1523 Paolo Giovio wrote with relief that “Rome triumphs without plague,” although he had not been in the city during the main epidemic. Nevertheless, plague continued to trouble Rome during Clement’s pontificate. The nobleman and author Baldassare Castiglione noted in July 1524 that the plague was “much diminished, but not extinct.” If Giovio’s population estimates from 1516–1517 are correct, the total population of Rome decreased by over thirty thousand in a decade, from approximately 85,000 to 53,897. In August 1524 Pope Clement VII had every motivation to view a poison trial as a measure that made both medical and political sense.

Published only a few days after the poison trials took place, the Testimonium was a slim pamphlet of just four pages. The pamphlet’s title described the trial of Caravita’s oil as an experiment conducted by “eminent men” at “the pope’s command,” and the document opened with a greeting “to all good mortals” from the three signatories: the Roman senator Pietro Borghese, the physician Paolo Giovio, and the pharmacist Tomasso Bigliotti.

The authors asserted that “it was reasonable and useful to everyone [for us] to have tested the virtues of the marvelous oil that Master Gregorio Caravita of Bologna created.” They also noted that Caravita had used the oil in “that time under Pope Adrian VI when Rome was devastated by a most terrible pestilence” and had “cured all sorts of men infected with pestilential disease in the hospital of S. Giovanni Laterano,” one of Rome’s smaller hospitals. By putting plague in the background, the authors both reminded their readers of the city’s misery under Clement’s predecessor and created a public justification for testing whether the antidote worked against poison. Pope Clement, indeed, specifically commanded that the test be conducted on “condemned bodies, for the public good.” Whatever Clement’s own fears of poison, the test of Caravita’s oil was depicted as a public benefit.

The two criminals chosen for the initial test were Corsican mercenaries named Gianfrancesco and Ambrogio. Corsicans, a minority population in Rome, were widely considered to be particularly violent and scurrilous, and mercenary soldiers doubly so. The two men had been convicted and sentenced in the court of the magistrates, although their specific crimes were not listed, and had been handed over to the executioner to be beheaded with an axe. The prisoner used for the second test, a Mantuan named Antonio, had been sentenced to death for murder.

None of these test subjects was likely to cause an uproar: all of them came from outside of Rome, the regular procedure of trial and conviction in the criminal courts had been followed, and all appeared deserving of punishment. These men would have been excellent candidates for a public dissection, had their death sentences occurred in winter. The authors of the Testimonium similarly indicated that they hewed scrupulously to religious conventions in the course of the trial. Accompanying the terrified convicts, they noted, was “a crowd of pious men,” who “by custom urged them to ask for forgiveness of their sins and said numerous prayers on their behalf.” These men were members of the Confraternity of San Giovanni Decollato (St. John the Decapitated), an organization that took charge of guiding condemned prisoners in Rome to a good, pious death. If they died in the right way with God, accepting their sentence and asking forgiveness for their crimes, executed criminals had the possibility of getting time off from purgatory—or even skipping purgatory altogether and going directly to heaven. Their presence was customary at all executions and once again signified that the proper procedure was being followed.

Not only did the criminals receive the expected religious ministrations, the pamphlet suggests, they also experienced a just punishment. Giovio and his colleagues instructed Caravita to anoint only one of the criminals (Gianfrancesco) with the marvelous oil, while the other (Ambrogio) was left to die “without any remedy.” They depicted Gianfrancesco as pious and repentant, ready to face his fate. Ambrogio, in contrast, was portrayed as sullen and rude, and he refused to cooperate with the testers. This unsubtle distinction between the “pious” and the “nefarious” criminal calls to mind the story of the two thieves crucified alongside Jesus, one penitent, the other unrepentant. The good and bad thieves were a familiar motif in Renaissance literature and art—including the images held up to condemned criminals by confraternities like San Giovanni Decollato, for whom the good thief represented the certainty of redemption. The contrast between Gianfrancesco and Ambrogio thus contained an unsubtle message: Gianfrancesco was worthy of being saved—spiritually but also, in this case, physically—while Ambrogio deserved his agonizing death.

Yet Gianfrancesco did not completely escape retribution for his misdeeds after he survived the poison trial. As punishment for his crimes, Pope Clement relegated him to the slave galleys. Antonio, the condemned criminal who survived the second poison trial, received a similar punishment: “The pope saved his life, yet banished him to perpetual rowing as a penalty for murder.” The two criminals who survived the poison had a special status that made Pope Clement hesitant to condemn them to death a second time. Yet they still had to atone for their crimes.

Giovio and his coauthors went to some lengths to emphasize that the trial of Caravita’s oil produced a valid and meaningful medical outcome. They described exactly how they sourced the poisonous aconite from the Apennine mountains, reduced it to a powder, and made it into sweet marzipan cakes. When the villainous Ambrogio refused to eat his marzipan, Caravita gave him an additional dose of the napellus mixed into an egg combined with sugar, “in order to subject both [criminals] to the same experiment.” Ambrogio was thus explicitly used as what we might now call a control subject. The authors also carefully detailed the effects of the poison—Gianfrancesco and Ambrogio were stricken by pains of the heart, paleness, nausea, and vomiting, while Antonio experienced great pain and became numb and cold. This gruesome detailing of symptoms provided evidence that the poison had worked, amplifying the recovery.

Reprinted with permission from The Poison Trials: Wonder Drugs, Experiment, and the Battle for Authority in Renaissance Science by Alisha Rankin, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2021 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.