cora gooseberry, freeman bungaree, queen of sydney & botany brass breastplate. Mitchell Library, Sydney, Australia.

It is tempting to think that the closest that one can get to the deceased is in the company of their possessions. For Cora Gooseberry such a notion is false and true in turn. Cora was an Eora woman. Eora is a term for over thirty clans of Aboriginal people who resided in the coastal Sydney region. She was the widow of Bungaree, who is often said to be the first person to be called an Australian in print.

R251B, a crescent-shaped brass breastplate said to have been worn by Cora, doesn’t weigh much as I examine it at the Mitchell Library in Sydney. The engraving on the breastplate’s front may be mocking how Aboriginal Australians engaged settlers. But I wonder whether the engraving provides some evidence of a sense of status adopted by Cora. It records in capital letters: cora gooseberry, freeman bungaree [her husband’s name], queen of sydney & botany.

Then there is R252, another object attributed to Cora, described as a “rum mug,” in bronze with a handle. It was a colonial idea that the Aboriginal Australians in Sydney of these years were addicted to drink.

R252 was collected in the nineteenth century by the book collector David Scott Mitchell, whose name now graces this library. Without citing any evidence, Mitchell told his assistant that the mug was larger at the top than at the bottom because “it had been enlarged by a marlinespike for her so that it would hold more rum.” Yet might this roughly formed mug show how Cora carried on finding her path within the port of what is now Sydney? Rum was itself a currency in colonial New South Wales. If so, the colonial trope of alcohol addiction needs to be forcibly rejected.

According to a Sydney newspaper of the 1840s, Cora was the “sister as far as regality goes of Queen Pomare” of Tahiti. This is in keeping with the use of a royal signifier—queen—in the breastplate too. Pomare IV of Tahiti intentionally deployed an image of herself as a queen, woman, and mother in the Anglo-French tussle over her fabled home. Yet there is a difference between Pomare IV and Cora. For Sydney was a city founded by a mass influx of white settlers, where Aboriginal Australians were wiped off the land. Indigenous peoples didn’t consolidate royal lines in Australia akin to those in Tahiti, Tonga, or elsewhere in the Pacific. If so, is the attribution of queenship to Cora simply an indicator of colonial rhetoric once again, like the use of the stereotype of alcohol addiction?

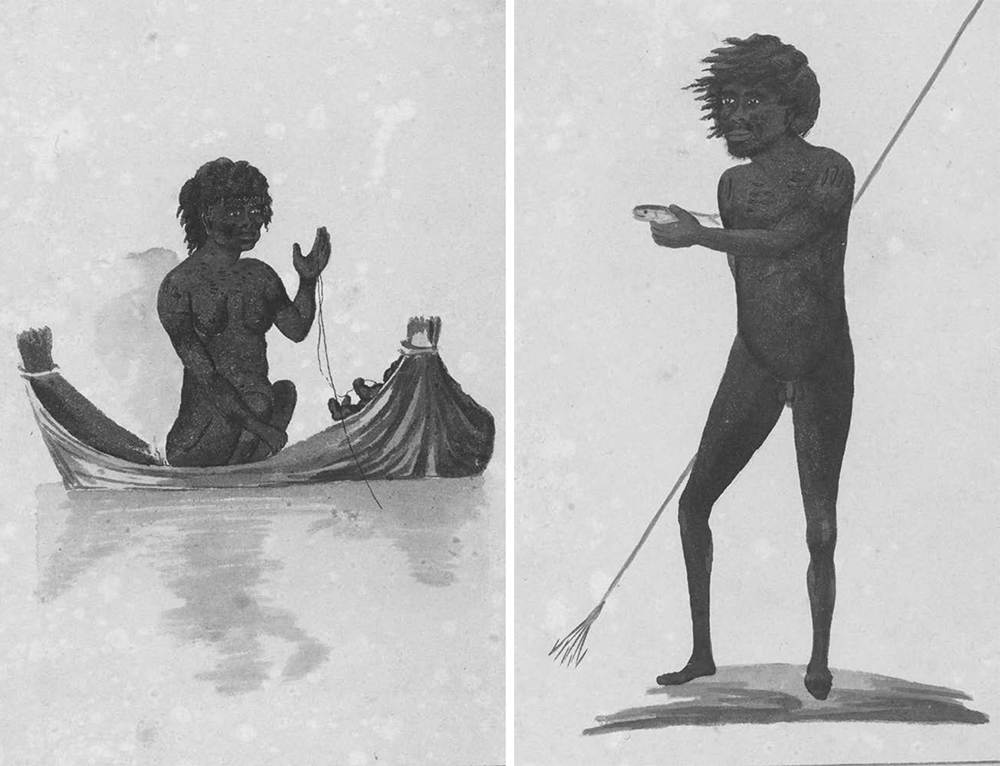

Both of Cora’s remaining breastplates are engraved with fish, and this may not be an accident. A set of watercolors attributed to George Charles Jenner—the nephew of Edward Jenner, the pioneer of smallpox vaccination—and thought to be from the early nineteenth century show Aboriginal Australians in portrait.

An Aboriginal Australian man waits, looking down into the water with his spear, as if in expectation of a fish. In another image, an Aboriginal man passes a fish on to someone outside the image. A woman sits in a canoe with her child and a line. Women’s involvement in fishing led at times to British men portraying them as sexually unattractive. George Worgan, a surgeon on the First Fleet, noted that Aboriginal women smelt of “stinking fish oil.” He wrote that they coated their bodies with the oil and this oil mixed with the soot which collected on their skins, because of the fires they kept on their canoes while on the water. Bearing out the sexual culture of settlement, he carried on: “From all these personal graces & embellishments, every inclination for an affair of gallantry, as well as every idea of fond endearing intercourse…is banished.”

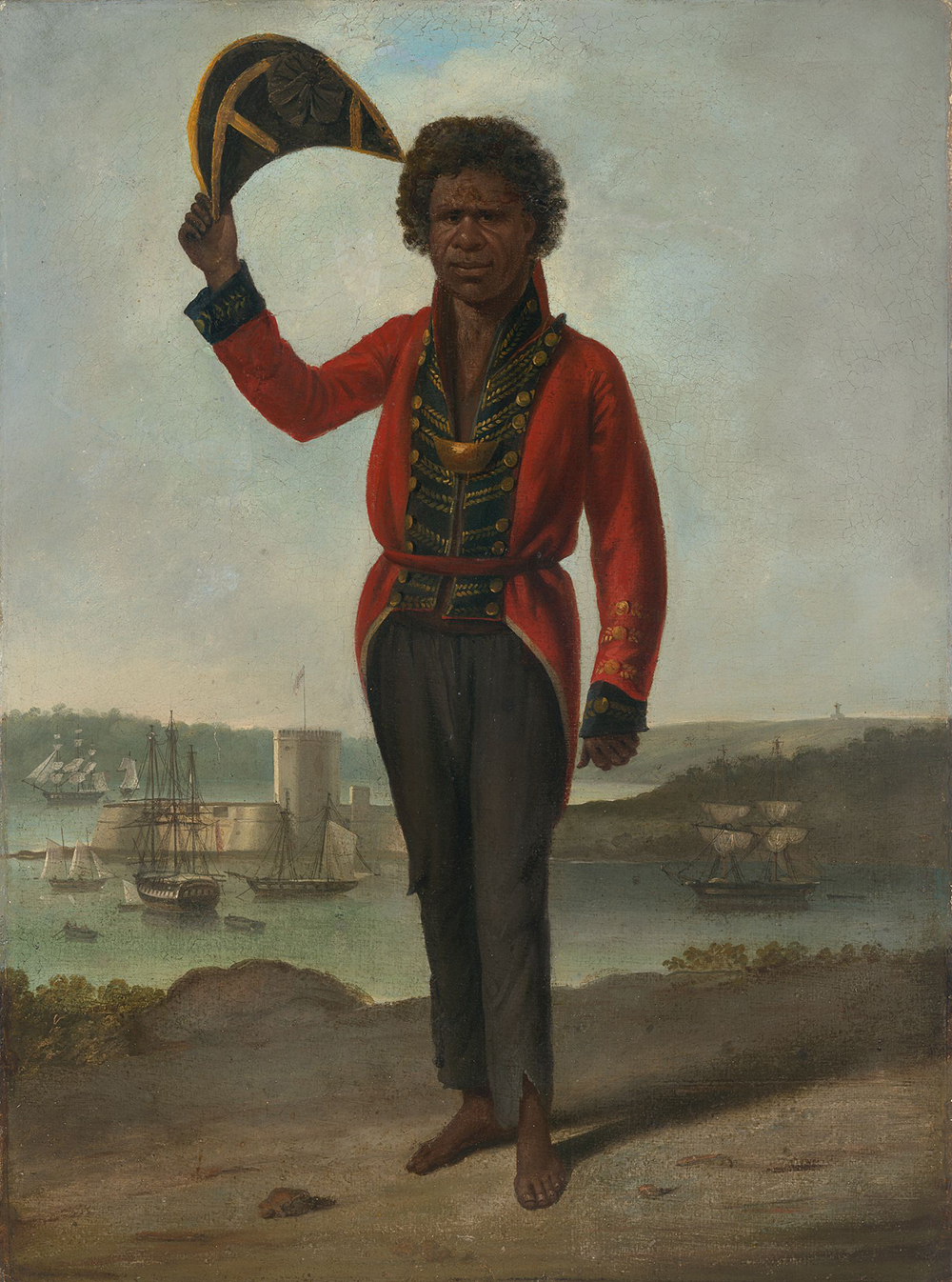

Cora’s husband, Bungaree, overshadowed her in the British vision. He had several wives. He circumnavigated Australia with the explorer Matthew Flinders, in the voyage that established the contours of the great island in 1801–3. The image that defines Bungaree’s reputation among the eighteen or more that remain of him is the oil painting produced by Augustus Earle.

It shows Bungaree in a chiefly pose. He is greeting the viewer and dressed as a general. He stands before Sydney harbor with three British warships and a vessel which may belong to the French expedition of Jules Dumont d’Urville. He wears a scarlet jacket. Bungaree was gifted military and naval gear that was no longer needed by the colonists. Lachlan Macquarie, the reforming governor of Sydney, gave him an outfit on the day before he left for London in 1822. In Macquarie’s words: “I gave him an old suit of general’s uniforms to dress him out as a chief.” The coat was presented in the midst of a “plentiful feast with grog,” and Macquarie asked his successor as governor to provide Bungaree with a “fishing boat with a net.” The conferral of the uniform coincided with the resettlement of Bungaree and his “tribe” in a farm on George’s Head. This gift giving and settlement was a reformist project consistent with Macquarie’s autocratic attempt to reorganize the colony.

The belittling of chiefly authority was obvious by the time a later version of this image appeared. An image from a collection titled Views in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (1830) shows Bungaree next to a woman: “The accompanying likeness represents him in the act of taking off his hat and bowing to the strangers landing, with one of his wives in company smoking her pipe.” The ships have now been replaced with bottles that glisten in a very dark blue. The houses in the background indicate the expansion of Sydney, and yet Bungaree and the woman with him, perhaps one of his wives, are detached from that project. The cut-and-paste style of representation which characterized British views of Aboriginal Australians had separated the genders. This new representation brought Bungaree to the foreground, and there is also a stronger view of racial difference in this image.

In Earle’s image a breastplate hangs around Bungaree’s neck, which reads bungaree, chief of the broken bay tribe 1815. Governor Macquarie initiated the tradition of presenting breastplates to Aboriginal Australians, drawing perhaps from his experience in America. Bungaree may have been the first recipient. After Bungaree’s death, his assertions of headship were retold in a racialized mockery of his alleged kingship. When he died, a broadside parodied the title which had appeared on the breastplate: aboriginal majesty king bongarie, supreme chief of the sydney tribe. Another described him as the “revered antipodal Majesty.” In 1857, in an age of anthropometric measurement, his skull was reportedly received at the Australian Museum, though no trace of it remains. In 1852 Cora was found dead of natural causes at the Sydney Arms Hotel on Castlereagh Street, having reached the age of seventy-five. Bell’s Life in Sydney, in publishing her obituary, noted that she “was the last descendant of the Sydney tribe of Aborigines; and her kingdom now is consequently not worth a gooseberry.”

In the cases of both Cora and Bungaree, the British adopted characteristic vocabulary for the time in order to reorganize Aboriginal Australians in line with reformist imperial programs of gift-giving and schooling. Aboriginal Australians were alternatively humored as monarchs, chiefs, and republicans. All these authorized liberal and humanitarian intervention as much as settlement. Settled family relations with ordered gender norms were critical to the project of civilization which Macquarie and his aides had in mind. This means that there were intimate dimensions to the transformation afoot as colonial vocabulary dominated indigenous peoples. In writing to London on the “character and general habits of the natives of this country,” Macquarie wrote of how Aboriginal Australian lives were wasted in wandering through woods, in small tribes of between twenty and fifty, acquiring subsistence from possums, kangaroos, grub worms, and “such animals and fish as the country and coasts afford.” He enclosed a letter from William Shelley, who presided briefly over the Native School connected to the Native Conference.

Shelley laid out the links between schooling and race and gender. The problem with raising indigenous peoples to Englishness was that “they were generally despised, especially by English females.” In advocating classes for boys and girls in separate apartments, in a school under his care, Shelley wrote:

No European woman would marry a native, unless some abandoned profligate. The same may be said of native women received for a time among Europeans. A solitary individual, either woman or man, educated from infancy, even well, among Europeans, would in general, when they grew up, be rejected by the other sex of Europeans, and must go into the bush for a companion.

The implication of Shelley’s argument is that “native” men needed to marry “native” women inasmuch as Europeans would marry Europeans. His school would serve the purpose of training such a corps.

With colonial norms imposed in this way, masculinity was Bungaree’s passport. It allowed him to become visible to Europeans and to come to the foreground of British representations of Aboriginal Australians. He first sailed with Flinders in 1799 on a survey voyage to Hervey Bay, north of present-day Brisbane, in a sloop named Norfolk, made out of the pinewood of Norfolk Island. In addition to later circumnavigating Australia with Flinders, he also sailed with Philip Parker King, son of the former lieutenant governor of Norfolk Island, to northwestern Australia in 1817. It is significant to note his entry into the large corpus of texts connected with Flinders’ work: “Bong-ree, a native of the northside of Broken Bay, who had been noted for his good disposition and open and manly conduct.”

In meeting indigenous peoples at Moreton Bay, while on the Norfolk, Bungaree wished to serve as emissary for Flinders. He opted to go ashore naked and unarmed, just as Aboriginal Australians appeared onshore. When with Flinders, Bungaree sought to fish as an Aboriginal male would around the coast of Sydney, by using his spear, without using the hooks and lines with which women would fish. On one occasion in a side-by-side show, three large fish were fired at by Flinders and speared at by Bungaree. But neither brought the catch up. On another occasion, Bungaree gave a spear and throwing stick to local people and showed them how to use them at Pumicestone River. Bungaree also presented himself as a naked emissary and also a spear thrower in the course of his circumnavigation of Australia and later while accompanying King.

Flinders was especially curious about how the people near the head of Pumicestone River fished and noted that their method was completely new to Bungaree, indicating perhaps Bungaree’s interest in their fishing, too:

Whichever of the party sees a fish, by some dextrous maneuver, gets at the back of it, and spreads out his scoop net: others prevent its escaping on either side, and in one or other of their nets the fish is almost infallibly caught. With these nets they saw them run sometimes up to their middle in water; and, to judge from the event, they seemed to be successful, as they generally soon made a fire near the beach, and sat down by it; no doubt, to regale with their fish, which was thus no sooner out of the water than it was on the fire.

From these observations about fishing Flinders built up a theory of cultural and racial difference. European notions of difference were overlaid on Aboriginal ones. Where nets rather than spears were used, Flinders argued that people would form associations with each other. Because nets provided a more certain means of procuring fish, their users would settle more regularly. Spears, on the other hand, explained the violence of Sydney: “An inhabitant of Port Jackson is seldom seen, even in the populous town of Sydney, without his spear, his throwing-stick, and his club…It is even the instrument with which he corrects his wife in the last extreme.”

Bungaree’s value could only be tolerated, then, if he conformed to the British class-driven type of masculinity which was often equated with gentlemanly warfare in the age of revolutions; Aboriginal senses of gender had to be subservient to this greater colonial identity and its polite civility.

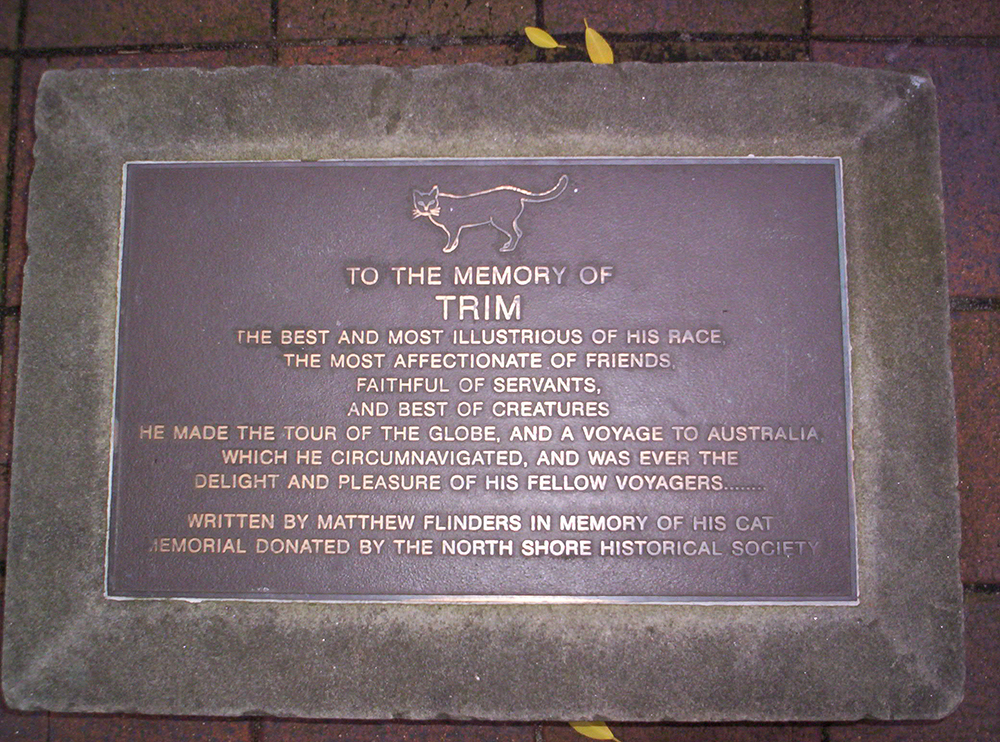

Outside the Mitchell Library stands a statue of Matthew Flinders, and it looks, in what would have seemed to British colonizers as proud and youthful manliness, at the street named after Governor Macquarie. It was dedicated in 1925 in return for the deposition of Flinders’ papers in the library. Bungaree does not figure here, nor of course Cora or Matora, another of Bungaree’s wives. Yet Flinders has recently been given another companion. It is Flinders’ favored cat Trim. Trim the cat is an Australian celebrity. Even the library’s café is named after him. Unveiled here in 1996, the plump Trim stands on his four legs behind Flinders and looks up to the right from beneath one of the outer faces of the library’s stained-glass windows. One of two plaques devoted to him reads:

trim. matthew finders’ intrepid cat who circumnavigated australia with his master 1801–3 and thereafter shared his exile on the island of mauritius where he met his untimely death.

It is partly as a result of a tribute penned by Flinders, while in captivity in Mauritius under Governor Decaen, that his cat has been raised to this pedestal. Flinders’ tribute bears the marks of someone with too much time on his hands, and is ironic and overly affected in turn. Trim appears as an astronomer and practical seaman and is said to be a cat of Indian origin. Flinders proposes that Trim is related to a cat who entered Noah’s Ark. Trim is also said to have formed a special relationship with Bungaree: “If he had occasion to drink, he mewed to Bongaree and leaped up to the water cask.”

The rise of Flinders as hero, together with his cat, corresponds to the displacement of indigenous peoples like Bungaree and Cora from historical memory.

Reprinted with permission from Waves Across the South: A New History of Revolution and Empire by Sujit Sivasundaram, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2020 by Sujit Sivasundaram. All rights reserved.