Portrait of a woman, by Jacob Byerly, c. 1855. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

In an 1846 story by the American dime novelist Edward Judson, a wealthy bachelor named Harry enters a Boston daguerreotype studio and finds himself enchanted by a photograph on the wall. The image is of a young woman, smiling while tears stream down her cheeks. There is something striking about her improbable expression; Judson informs us it has the “power of utterance.” No wonder that Harry is instantly entranced. He begs the daguerreotypist to sell her image.

You may laugh at me, and call it a boyish freak to love at first sight, but I love this girl, yes, I love, and will not rest till I have found her out, and if pure, devoted, unselfish love will win her, I will marry her.

Such a conjugal plan, formed on the basis of a photograph, may not have struck Judson’s readers as entirely advisable. But it would not have appeared particularly unusual. Writers, journalists, and their audiences were captivated by the potential of the daguerreotype—an early form of photography that involved exposing a silver-plated sheet to a camera lens and mercury vapors—to kindle romantic affection. That one might encounter a stranger’s portrait and fall instantly in love was not, as it might appear today, the far-fetched plot of an outlandish romance. It was a familiar scenario, driven by the expectant fantasies and exalted fears that a new technology can sometimes inspire.

In stories like “In Love with a Daguerreotype” (1859) and “The Twin Daguerreotypes” (1855), a glance at a woman’s portrait throws her male viewer into such frenetic delight, he either hides her image under his pillow for months or travels thousands of miles cross-country to reach her home. The trope was so common that Harper’s spoofed the emerging genre in an 1855 satire in which two daguerreotypes fall in love. The article sardonically notes that such a love affair “is scarcely to be wondered at,” considering its occurrence is “very frequent among the class of human species.” By human species, the caustic Harper’s writer more accurately meant fictional species. There is little evidence, from wedding announcements to newspaper articles, that couples regularly met from a stray glance at each other’s daguerreotypes. And yet in penny press romances, it appeared a generation of young people were leaping into lightning-fast engagements, entranced by a few silvery inches of a stranger’s face.

The American daguerreotype craze began on April 20, 1839, when the inventor Samuel F.B. Morse traveled to Paris and wrote a glowing letter to his brother about the new technology pioneered by the French artist Louis Daguerre. In Morse’s letter, later published in the New York Observer, he praised the daguerreotype as “one of the most beautiful discoveries of the age,” capable of rendering “perfect representations of the human countenance.” Months later, Morse and other American scientists began experimenting with Daguerre’s invention. By 1853, between 13,000 and 17,000 individuals offered daguerreotype services in America. Because daguerreotypes weren’t as costly as paintings, which involved multiple sittings and hours of labor, images became newly accessible to the middle class. For the first time, the people represented in pictures weren’t exclusively rich and royal, which meant it was newly realistic, and possibly even in reach, to covet the subjects of such images.

You might encounter unknown faces in studios, homes, pockets, or even carelessly dropped on the street. But even as daguerreotypes became common objects, they retained an intensely intimate association. Daguerreotypes were typically exchanged between loved ones; family members carried miniatures in lockets, friends exchanged images as tokens of affection, new couples framed pictures in wedding attire. Although the images occasionally served a more commercial purpose—to attract patrons, daguerreotypists occasionally displayed client portraits, and some shops sold images of famous authors, politicians, generals, and actors—if you saw a portrait in a locket or a frame, it was likely because they were special to you. Perhaps a stranger’s daguerreotype evoked a feeling of transgressive familiarity, a sense of witnessing someone from an improperly close distance.

Unlike paintings, which were understood to present a certain bias, daguerreotypes were treated as factual records. Victorians were surprised by their minute detail; as one writer for the Gentleman’s Magazine marveled in 1839, daguerreotypes captured everything from “the humidity caused by the rain,” to “the inscription on a shop sign.”

Scientists predicted daguerreotypes would eventually be used to keep medical records, inspect insects’ anatomy, or even be sold as miniature novels read via microscope. Writers treated daguerreotypes with similar deference. When Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote that she would “daguerreotype” Uncle Tom, she meant she would offer a specific and frank description of his physical appearance. Indeed, the alluring picture that Harry encounters in the daguerreotype studio, the narrator informs us, is “exceedingly true and lifelike.” And yet, along with its air of scientific precision, the process of creating a daguerreotype was also thought to have a mystical ability to reveal a person’s true nature. As literary historian Susan S. Williams notes in Confounding Images: Photography and Portraiture in Antebellum American Fiction, “writers imagined that the ‘light of Heaven’ could search out daguerreotype subjects in moments of private weakness and reveal truths that were repressed or hidden in more carefully fashioned public poses.”

When Harry looks at the daguerreotype, he isn’t simply drawn to an unfamiliar woman’s impressive looks. The narrator assures us that she isn’t, by standards of the day, a quintessential beauty; her curly hair is unkempt, her eyebrows too thick, her black silk dress pilling and torn. But Harry believes something essential about this woman—her temperament, her interior world—is made legible through her expression. “Her character has been written by her maker upon her countenance!” he exclaims. Harry’s conviction would become something of a prevailing thesis in the many daguerreotype stories that followed: sight was not a superficial sense, but one with the power to reveal a stranger’s secret core.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, most accounts were skeptical, if not downright pessimistic, about any passion born from a swift encounter. “Term not that Love which rises at first sight, / That unrefin’d, gross, ocular desire,” counseled a typical poem published in Philadelphia’s Port Folio in 1805. The erotically naïve bumpkin who falls for the first beautiful woman he sees propelled many comic plots. In “Love at First Sight; or the Fish Out of Water” (1838), a recent college graduate named Paul Pimpernel becomes infatuated with a woman he spots on an afternoon walk. But he soon discovers his beloved is not quite “so frank, so gentle” when he discovers her “late” husband is very much alive. Paul is thus taught the importance of a conventionally protracted courtship.

But by mid-century, Victorians had begun to legitimize love at first sight. In stories published from 1843 to 1858, a split-second of sight compels a young Bostonian to follow a beautiful woman to New York, a smitten suitor to track down a woman he spots from the window of a moving train, and a wealthy lawyer on a forest romp to propose to a farmer’s daughter with “soft” blue eyes. Each of these stories ends in unquestionable victory when the woman seen from afar turns out to be gentle, decent, and virtuous. Perhaps there is good sense in looking, as one 1850 story suggests, “with a spirit-like token of kindliest recognition, not wanton or passionate, but pure as the gaze of an angel through starry haloes.”

Some writers took this idea to its extreme, arguing that sight wasn’t only an appropriate way to choose one’s life partner, but preferable to a period of extensive rumination. “There is no love but love at first sight,” the conservative British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli wrote in his 1837 novel Henrietta Temple. “All other is the illegitimate result of observation, of compromise, of expediency.” Indeed, in Henrietta Temple, an “expedient” and financially pragmatic engagement proves disastrous and is quickly undone when the novel’s hero stumbles upon a woman he sees and loves effortlessly. In Disraeli’s narrative, love is incapable of developing through time, observation, or exertion. “Miserable man whose love rises by degrees upon the frigid morning of his mind,” he writes.

What forces, exactly, had conspired to transform an “unrefin’d, ocular desire,” into the “gaze of an angel through starry haloes”? By the mid-nineteenth century, a new romantic ideal had emerged: the love match, a marriage in which spouses not only raised a family and managed a household together, but adored each other. The Victorian era was one of the first in which partnerships were not exclusively determined by parents and arranged primarily for mutual economic and social benefit. Marriage was transformed, as historian Stephanie Coontz writes in Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage, into “the pivotal experience in people’s lives,” as well as “the principle focus of their emotions, obligations, and satisfactions.”

In place of traditional marital goals, like protecting family property and forming strategic alliances, this new ideal emphasized the pure and rarified motive of romance. And what could be more romantic—based entirely on the tender passions, rather than worldly ambitions—than falling in love at first sight? When Harry learns his beloved is a poor seamstress, he doesn’t think twice: “I care not for that; were she a kitchen maid, and as pure, true, warm-hearted and good, as I know she must be from the angelic expression here depicted, I would as soon take her to my heart as if she were a crowned queen of Europe.”

As an expression of love at first sight, daguerreotype romances offered a particular advantage; they made encountering a stranger a less unwieldy experience. As journalist and historian Kathryn Hughes writes in Victorians Undone: Tales of Flesh in the Age of Decorum, the nineteenth century saw an exodus from sparse rural towns to swarming cities, where urban dwellers were inundated by inescapable smells, sounds, and sights. To protect oneself from the onslaught of corporeal chaos, the Victorian approach was to avoid thinking or writing about the many bodies one came across in daily life. As Hughes writes, “If flesh and blood registered in Victorian life stories at all, it was in the broadest, airiest generalities.” The daguerreotype made it possible to experience a stranger’s features in such broad and airy strokes—without confronting smelly pits, stale breath, squeaky voices. By boiling down the senses to a manageable confrontation, the daguerreotype came close to the ideal of love at first sight, as described in one 1850 story, “pure as the gaze of an angel.”

But perhaps stories of love at first sight contained a kernel of that old, familiar pragmatism, simply recast for a new generation. In his 1886 essay, “Falling in Love,” Canadian scientist Grant Allen encouraged men not to be ashamed of that “divinest and deepest of human intuitions, love at first sight,” because it offered “the latest, highest, and most involved exemplification, in the human race, of that almost universal selective process which Mr. Darwin has enabled us to recognize.” Should men ignore their eyesight and marry an “ugly” and “hysterical” heiress (“almost by necessity the one last feeble and flickering relic of a moribund stock”), Allen predicted she’d deliver sickly, unhappy children. Better, Allen concluded, to marry the sprightly farmer’s daughter, even if she happens to be penniless.

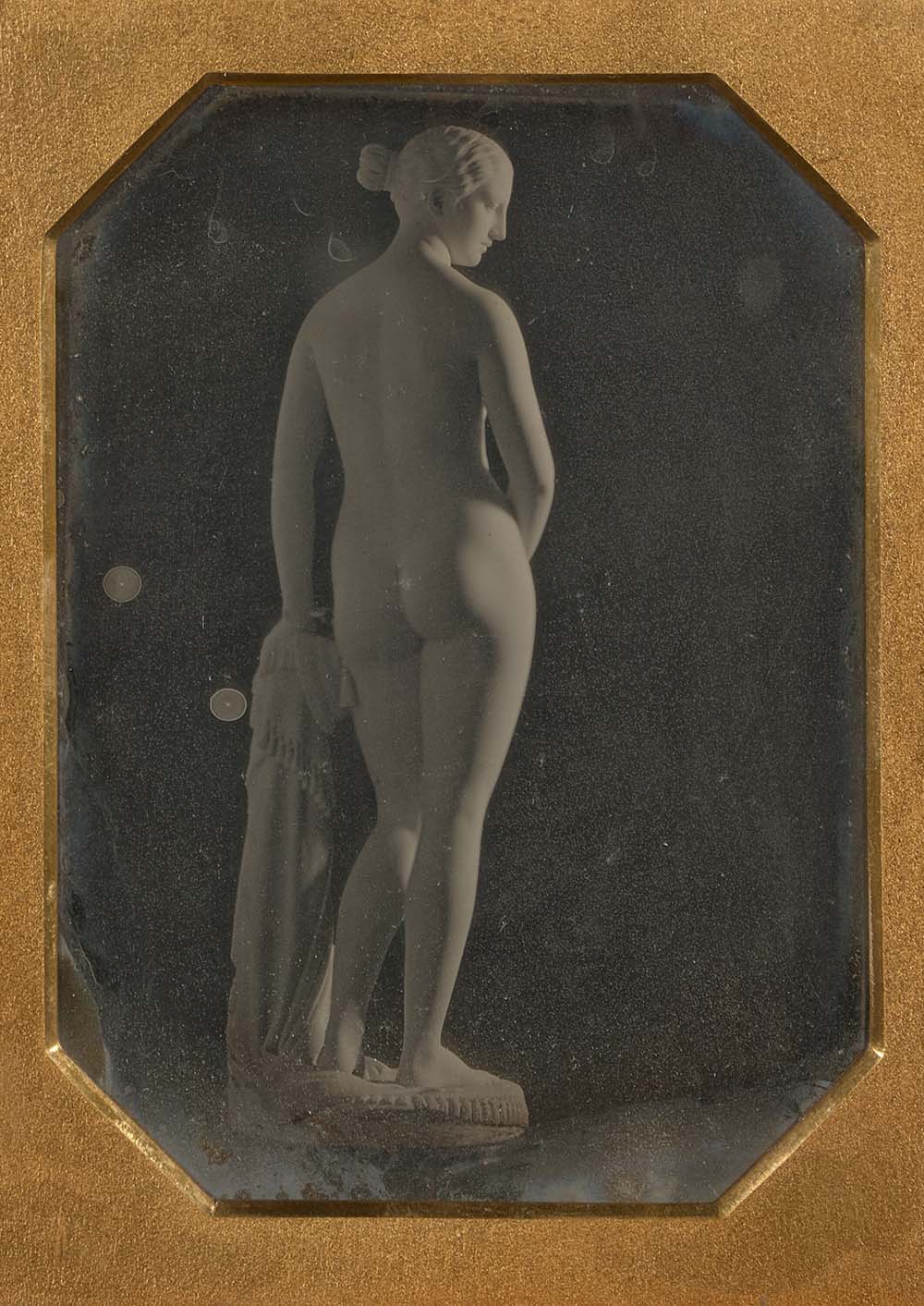

In a sense, Allen’s advice mimicked an ancient form of matchmaking: exchanging commissioned portraits. It was common practice for royals, from the Han dynasty to the Tudor kings, to solicit sketches and paintings of eligible women for romantic consideration. If a woman was deemed unattractive (or simply refused portraiture, as Giovanna of Aragon famously did when Henry VII presumptuously sent his artists to Naples to obtain her likeness), she’d be eliminated from a pool of wifely applicants. While it may have been an added benefit for a king to be attracted to his wife, this assessment of images had little to do with Victorian ideals of love, ardor, and passion. The point was to filter out women who wouldn’t conceive good-looking heirs.

Just as portraits of women through history were given to powerful men for their scrutiny, and Allen’s advice was made specifically to men, in Victorian romances that “gaze of angel” almost always belonged to a man. It was fictional men who produced, circulated, bought, and fell in love with daguerreotypes, often without the knowledge of their female subjects. When Harry stumbles into a studio, he happens upon the striking image because a penniless woman named Fannie has been forced into an uncomfortable bargain: she has allowed the daguerreotypist to display her image on the wall in exchange for a free photograph. She ponders “the propriety of permitting her likeness to remain where all the world might gaze upon it,” but ultimately, “her love for her brother,” a naval officer whom she plans to send her portrait, “conquered all other feelings.” In other stories, photographs of women are seen because of extenuating circumstances; an image sent to a friend is inadvertently misplaced, a sibling reveals a portrait to an acquaintance, a photograph is dropped in a bustling street.

There was often an odd split in daguerreotype romances between a women’s likeness, which might circulate freely in the world, and a woman herself, who was often carefully ensconced at home. In the popular 1846 story “The Daguerreotype Miniature or, Life in the Empire City” a young bachelor, Arthur Warden, falls in love with the daguerreotype of the beautiful Rose Warrington, and carries the image with him through a series of urban escapades that include running away from a pair of bloodthirsty thieves. Although her likeness accompanies Arthur on his adventures, Arthur encounters the real Rose only in snug domestic settings: carefully tucked away in a carriage or in her father’s home.

Interestingly, the popular story was reissued over ten years later under the new title “Rose Warrington; or the Daguerreotype Miniature.” The text wasn’t altered, but printed on the front cover of the new edition was a somewhat incongruous drawing, in which Rose holds a two-inch portrait of Arthur, her hand fixed to her heart. Below, a caption explaining the picture reads, “Rose Warrington contemplating the daguerreotype of Arthur Warden.” The actual story featured no such scene; Rose never looked at, let alone lusted after, Arthur’s image. But the choice to feature this new cover and title does seem to hint at the growing desire from a largely female reading public to participate in an emerging romantic fantasy.

In many ways, love at first sight was an epistemological fantasy about finding a foolproof way to comprehend someone’s character. The rise of the compassionate marriage had made choosing a mate the purview of a potentially gullible young person, instead of adults and guardians, which led to much vociferous anxiety about how to pick the right partner. Should one undergo a series of courtship rituals and careful deliberation? Or seek something more shadowy, illusive, and instinctual—an electric, instant attraction?

It’s not surprising that women craved access to romantic knowledge that could protect them from making a poor choice; after all, marriage was a particularly important and perilous endeavor for women. In the nineteenth century, new values of motherhood and domesticity encouraged women—particularly if they were white, Protestant, and upper- or middle-class—to make the home a center of spiritual, moral, and civic fulfillment. Not only was there growing cultural pressure on women to find fulfillment in family life, but women had little legal recourse if their marriages didn’t work. Women couldn’t vote, own property, make wills, sign contracts, or initiate divorce. While some states began reforming divorce laws in the mid-nineteenth century, a woman looking to end her marriage faced a challenge that ranged from arduous to impossible.

Even in states with more modern divorce laws, judges often ruled against women, even in cases of extreme abuse. In New York City, for example, a judge refused a divorce in 1861 to a woman whose husband had beaten her unconscious, arguing that “one or two acts of cruel treatment” didn’t merit breaking the “sacred tie” between husband and wife. No wonder women were intrigued by the fantasy of daguerreotypes, a new technology seen at once as scientifically precise and imbued with a mystical ability to reveal truth, and to offer a privileged insight into a man’s character.

But who, exactly, created these fantasies in the first place? The mind behind Harry, Edward Judson, better known by his pen name, Ned Buntline, was a naval officer, magazine editor, novelist, and temperance advocate who also happened to be an infamous drunk (often lecturing under the influence) and outspoken supporter of the jingoistic Know Nothing party known for harassing Catholics and immigrants.

Judson’s romantic life was equally elaborate and confounding. At seventeen, he married Severina Marin, whom he met in Havana. After she died, he married the nineteen-year-old New Yorker Annie Abigail Bennett, who shortly after divorced him for infidelity. The pace picked up from there: he next married his publisher’s widow, Lovanche L. Swart; abandoned Swart while at a hotel in Boston for the Jewish actress Ione Judah; split from Judah and returned to Swart; married Anna Fuller, unbeknownst to Swart; left Swart and Fuller for Catherine Myers; moved with Myers to a cabin in the Adirondacks called Eagle Nest, which happened to be to the gravesite of Eva Gardiner, another ex-wife who had died during childbirth; and finally reconciled with Fuller, who he lived with until his death. Perhaps the difference between Judson’s prolific affairs and the tidy marriage plots he dreamed up in penny-press fiction reflects a reason so many Victorians were enchanted by daguerreotype romances. The more marriage proved to be a risky endeavor in life, particularly for women, the more readers devoured stories that imagined an omniscient and infallible form of courtship.

In the late nineteenth century, a new romantic plotline would appear, inspired by another emerging technology: the telegraph. In Ella Cheever Thayer’s 1879 novel Wired Love: A Romance of Dots and Dashes, two operators begin a virtual flirtation. After exchanging dozens of messages, one emphatically declares, “I hope sometime we may clasp hands bodily as we do now spiritually, on the wire—for we do, don’t we?” Once again, an industrial advance had roused writers to envision a changed courtship; only now it was one’s words, not one’s body, that assumed the power to reveal a “spiritual” connection. Perhaps falling for a spectral mind on the page sounds opposite to desiring a pretty face. But each were fantasies of purity, of a romance filtered of fleeting affection and self-interested motivation. In a sense, the central dream remained the same: that technology might remove the pollution, odiousness, and clutter of life from love.