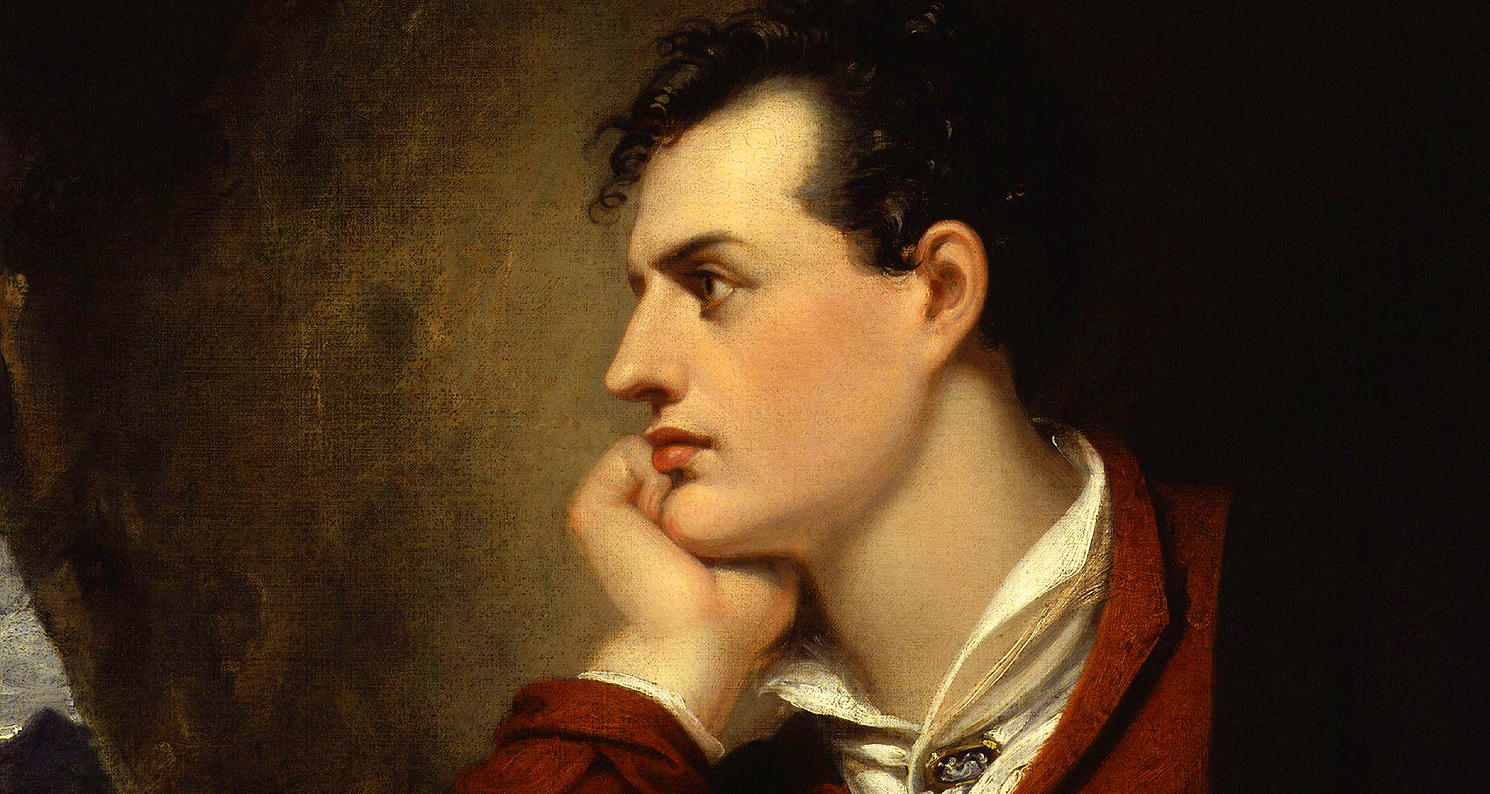

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, by Richard Westall, date unknown. National Portrait Gallery.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

On the evening of April 5, 1815, Mount Tambora, in the Indonesian archipelago, lost its head. So furious was the volcanic eruption that the top third of the 4,300-meter mountain disappeared. More than 10,000 people were incinerated, while an additional 30,000 across the world perished from the crop failures, famine, and disease that resulted from extreme weather triggered by the explosion. Volcanic ash blotted out much of the sun for more than a year, seeding wild rumors that the sun was dying. In Europe and North America, there were snowfalls in June, dry fogs, streaky sunsets, and unseasonal storms. The average global temperature dropped by a whole degree. The climate changed overnight.

Unexpectedly, however, this catastrophe spurred two remarkable works of apocalyptic literature in distant Europe. As we mark their bicentenary, these works can be viewed as forerunners to the literature of climate change.

The more famous of the two is Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein, the mesmerizing and moving story of a hubristic scientist, Victor Frankenstein, who creates a yellow-skinned and watery-eyed monster in his laboratory—and then loses control of it. It has become the classic cautionary tale against what Shelley’s vainglorious scientist upholds as “the unquestioned belief that the products of science and technology are an unqualified blessing for mankind.” The other is the lesser known but equally haunting poem “Darkness,” by the romantic poet George Gordon Byron. It imagines the horrific end days of human life on an earth that has become “a lump of death—a chaos of hard clay.” These two works share a unique kinship: not only were they goaded into being by the gloomy Tambora weather, but they were conceived in the same month, July 1816, and in the same place—on the shores of a storm-lashed Lake Geneva, where Byron and the Shelleys had rented neighboring villas.

The story of how Frankenstein was born has passed into literary legend. The year 1816 was known by the clammy epithet of the Year Without a Summer; thunderstorms and what Mary described as “an almost perpetual rain” kept them indoors. The group of friends—which included Byron’s personal physician Dr. John Polidori and Claire Clairmont, Mary’s eighteen-year-old stepsister, who was madly in love with Byron and pregnant with his child—decided to pass the time by inventing ghost stories. Eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley came up with Frankenstein, whose opening page, shivery with icy winds, manifests a deep longing for a place where “the sun is forever visible.”

The roots of Byron’s poem, which was composed first, are darker and far more twisted. Byron wrote this poem at the most degraded point in his life. If “Darkness” is infused with a cold and wolfish spirit untouched by kindliness, it is because it reflects not merely the strange weather outside but also the despairing inner weather of the poet’s soul. In four years, he had gone from being the cynosure of the bon ton—when a wave of “Byromania” had swept England after the 1812 publication of the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage—to a social and moral pariah.

In April 1816, the twenty-eight-year-old poet had left England in disgrace, and though he did not know it then, he would never see his country again. Nor would he again see his infant daughter, Ada. The future math genius was the result of a single year of marriage to Anabella Milbanke. Shocking cruelty on Byron’s part—he had repeatedly attempted to rape her days before and after the birth of Ada—and a sexual relationship with his half-sister Augusta (an amour fou he flaunted in his wife’s face) wrecked their union. Rumors of his affairs with young men were rife. Drunk, divorced, and in debt, his grand library of books auctioned off, and even his birds and squirrel seized, Lord Byron left England garlanded with an unholy trinity of scandal: sodomy, incest, and marital cruelty.

Traveling in a lumbering coach designed to replicate one owned by Napoleon Bonaparte, Byron went to Waterloo to pay his respects at “this place of skulls, / The grave of France,” the shrine of his fallen hero. What Napoleon had achieved in politics and warfare, the critics had said, Byron had achieved with his stirring and unorthodox verse. And therein lay another wound. Napoleon—whom Byron and his romantic confreres had cheered on as a dynamic antidote to the moribund British monarchy (“A King who can’t—and a Prince Wales who don’t / Patriots who shan’t—Ministers who won’t”)—had betrayed them with his bloodlust and megalomania. But even so, his defeat in 1815 had come as a grievous blow to them. On many a brandy-and-laudanum-fueled evening, an unhinged Byron had been caught impersonating the emperor. Napoleon was in exile now, and so was he. He had become a parodic version of the shunned Byronic hero, and like the brooding Childe Harold, was “sore sick at heart.”

At Geneva, he rented the luxurious lakeside Villa Diodati, next to a more modest one rented by Percy and Mary Shelley. The Shelleys had planned to go to Italy, but Claire Clairmont, who was pursuing Byron, had heard he would be in Geneva and was determined to be there as well. The two poets met outside their hotel, with the club-footed Byron, who had returned from a boating trip, limping up the pebbly beach to meet Shelley, who was out on his morning stroll. Despite their notoriety, both men were shy and awkward, but immediately warmed to each other. Soon inseparable, they spent the next three months discussing poetry, sharing long wine-laden meals, and boating on the lake. Meeting Percy Bysshe Shelley every day was something Byron dearly looked forward to, and their Geneva holiday marks one of the great and most productive literary friendships in history.

One July afternoon, when Byron was alone, he noted that the day was so peculiarly overcast that “the fowls went to roost at noon, and the candles were lighted as at midnight.” Unnerved but inspired, his anguish came pouring out. Written in cascading blank verse, “Darkness” would be his most pessimistic poem. The opening stave echoes the widespread fears that the earth was moving toward an everlasting night:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Terrified of being doused by darkness, people everywhere searched for heat and light. Byron, like everyone else in Europe, was completely unaware that a volcanic eruption in Asia was the cause of the thunderstorms and tenebrous skies. As a result of this ignorance, he wrote what must be some of the most grimly ironic lines in the history of poetry:

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain’d;

In this inglorious new world, the order of nature is overturned. Using fearful imagery plucked straight from the Book of Revelation, he describes predators that have become “tame and tremulous,” while “hissing, but stingless” vipers are slain for food. As the “pang of famine fed upon all entrails,” even dogs have begun to attack their masters. The earth has shrunk into a “seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless” lump, and sailor-less ships are “rotting on the sea”—a potent image of paralysis no doubt taken from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Even more arresting is the scientific precision of the lines:

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir’d before

In spite of these apocalyptic conditions, two men survive. Is there hope, then? Byron is no mood for redemption or happy endings. His two survivors are sworn enemies. In a grotesque climax reminiscent of ancient sacrifice, they come face-to-face at an altar where, over dying embers, they beheld

Each other’s aspects—saw, and shriek’d, and died—

Even of their mutual hideousness they died

Humanity’s last survivors, whose faces mirror each other’s bestiality, have self-destructed out of self-loathing—an emotion Byron was all too familiar with even if he unfailingly cast himself in the role of victim. What makes this poem remarkable is that it is both intimate and cosmic, as much a self-scourging as a lament on a loveless universe threatened by what seemed like an existential crisis. Europe, ravaged by decades of Napoleonic wars, was now being battered by nature. Germans were reduced to eating sawdust bread, and famine refugees were streaming out of Ireland and Wales. As cattle died and wheat, oat, and potato harvests failed, food riots broke out everywhere. Nor could people understand the lurid twilights and abnormally cold weather. Street-corner prophets predicted all manner of doom.

All this anguish pours into the poem, a floe of black ice, which ends on a note of absolute desolation:

Darkness had no need

Of aid from them—She was the Universe.

Explore Disaster, the Spring 2016 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.