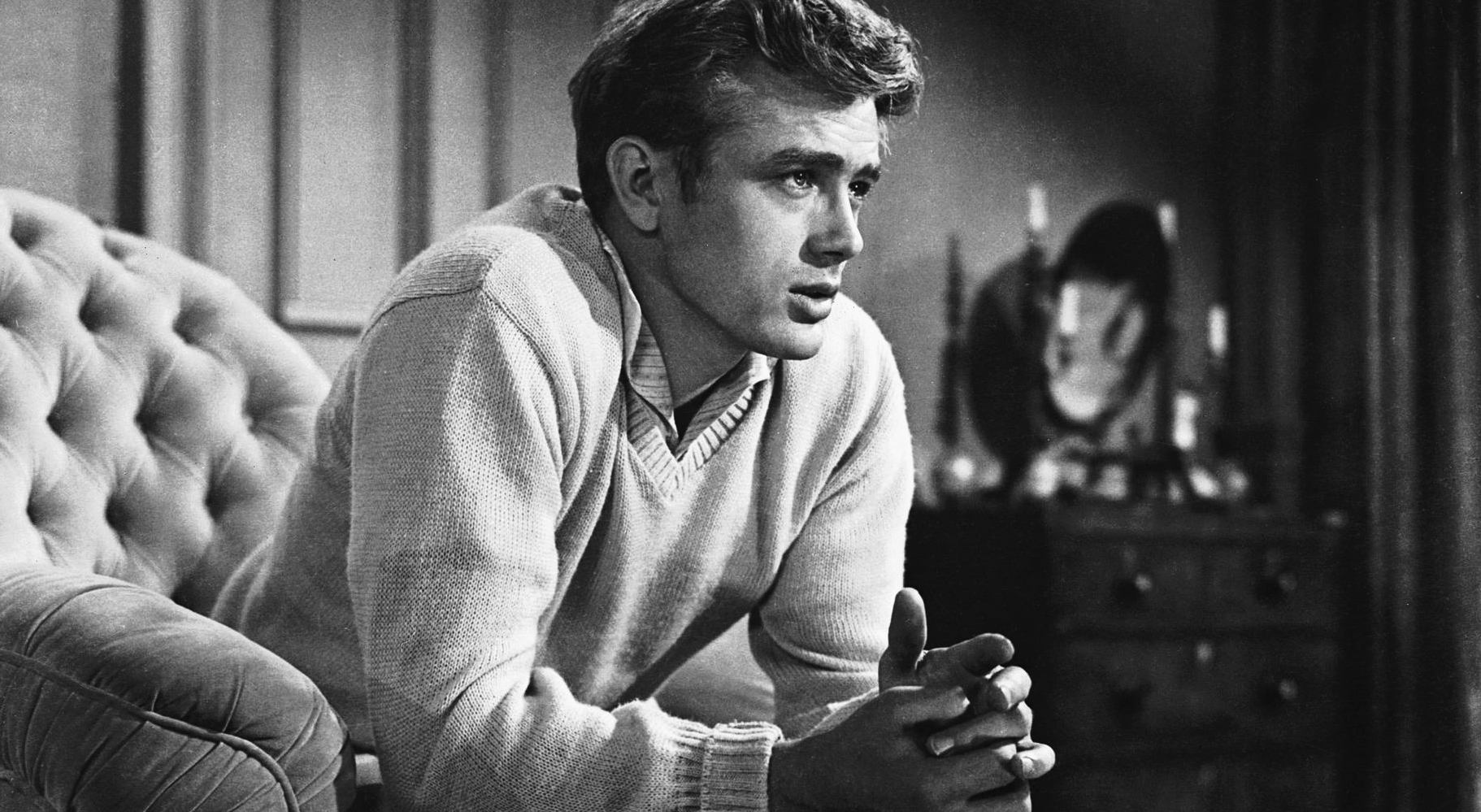

James Dean in East of Eden, his first major movie, 1955. It was the only film starring James Dean that would be released in his lifetime.

Everyone thinks they know the tragic story of James Dean: he died young and violently, he embodied the ennui and angst of the postwar generation, and his image lives on as a hollow signifier of youthful rebellion. But most don’t understand how the timing of his death, and the very specific timing of his films, turned a tragic death into a cultural crater—one that would be widened and exploited by the publishing industry.

In the early 1950s, Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando tore through Hollywood, establishing themselves as “angry young men” who refused to hew to a classic understanding of Hollywood acting or behavior. They were astounding onscreen: both had a visceral, emotive magnetism. Critics loved them, execs were confused by them, and girls went nuts for them. Part of it was palpable sex, especially Brando’s, but it was also the vulnerability. These young men were just as sensitive as every teen girl dreamed their boyfriend would be. Brando and Clift raged against structural limitations, mostly to do with class, that may or may not have been relatable to most teenage girls, but it was the way these men crumbled, and the hope that the love of a good woman could put them back together, that animated so much female (and unspoken male) desire.

With his rebellious image, James Dean is often grouped with Clift and Brando, but he was seven years younger than Brando and eleven years younger than Clift, and his childhood during the war years would always distance him. Clift and Brando were in their late teens and early twenties during the Second World War; neither served, but it was a defining experience in a way it could never be for Dean. It was this sense of “missing out” that structured Dean’s image and performances. He didn’t have a war—so what did he have? People called that unspeakable lack “rebelliousness,” but it was always something more: which is precisely why his image, even flattened out by endless movie posters, endures.

In the beginning, though, Dean was just a bit of a punk kid. He lost his mother at a young age, and spent his late adolescent and teen years bouncing between his aunt and uncle’s home in Indiana and his relocated father’s home in California. He was always smart and quick on his feet; he was the captain of the Oratory Club and seemed to inspire the sort of love that teachers have for wounded, brilliant children. But he was also somewhat aimless: he enrolled in a smattering of classes, tried to join a fraternity, and eventually made his way to New York, where he started taking classes at the Actor’s Studio. A string of bit parts, some relatively risqué stage work, and Dean found himself cast in Elia Kazan’s loose adaptation of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, in which two brothers vie for the farm and the love of the same woman.

When Dean returned to Los Angeles, he had the chip on his shoulder that young people who’ve lived in New York for less than a year seem to accumulate. He slouched around the Warner Brothers lot and wrote frantic letters to a would-be girlfriend. Mostly he thought of Brando and Clift, making no secret of his desire to emulate them, periodically signing his name James [Brando Clift] Dean. He wanted act like them, sure, but more importantly, he wanted to be like them. He loved fast cars and motorcycles, he wore blue jeans and white t-shirts, jumping between petulance and utter sincerity in interviews.

East of Eden was a hit, and the comparisons to Brando were immediate. But Dean began shooting Rebel Without a Cause just one week after the release ofEden in March of 1955, and after wrapping Rebel, he moved almost immediately on to Giant, this time alongside Rock Hudson and Elizabeth Taylor. The publicity machine was churning out content—gossip columnist Hedda Hopper thought he was wonderful—but Dean was still relatively unproven. He was a handsome and compelling presence on screen, but still just one of dozens of would-be teen idols still being tested by the Hollywood star machine.

And then the crash happened, Rebel Without a Cause hit theaters less than a month later, and seemingly overnight, the Dean image became mythic.

The details of Dean’s death have been narrativized at length, but the short version goes something like this: Warner Brothers had banned him from racing while he was shooting Giant, so as soon as the film wrapped, he took his newly-purchased Porsche 550 Spyder and his mechanic Rolf Wutherich on the road, with intentions to compete in the Salinas Road Race. Traveling between 75 and 100 miles per hour, the Porsche collided head first with a Ford Coupe at 5:30p.m. on September 30, killing twenty-four year old Dean and leaving Wutherich in serious condition.

The death was a shock and a tragedy, but it wasn’t front page news. At this point, Dean had only appeared in one film, East of Eden. But Warners also understood that they could use Dean’s death, and the uncanny similarities to his character’s actions in Rebel Without a Cause, to turn a teen movie into a bona fide hit. By the time Rebel opened in late October, the fan magazines were flush with content, all promising unique revelations concerning the “real” Dean, his love life, his childhood, and his “death drive.”

And so the cycle began: the more information the magazines provided about Dean, the more the audiences demanded. It’s a cycle that should be familiar to anyone who watched the O.J. Simpson trial or the coverage of the death of Anna Nicole Smith: pique a reader’s appetite correctly, and soon that appetite will be voracious.

Rebel Without a Cause would go on to gross nearly five million at the box office, the fifth highest of the year, and a true coup for a low-budget teen film. Since Rebel attracted fans for months, some for nearly ten viewings, Warner Brothers held onto the now-completed Giant, releasing it one year and one week after Dean’s death. His Giant character was markedly different than the teenager he played in Rebel—he looked older and acted surlier, his heart was somehow colder, less savable. But no matter: here were two hundred sellable minutes of Dean, and no amount of aging make-up and sneering could mask his unceasing devotion to the married Elizabeth Taylor, the love of his life.

With these two movies, Warner Brothers exercised immaculate timing and made millions, but their exploitation paled in comparison to the work of the fan magazines which were on the brink of crisis in mid-1950s. With the slow dissolution of the studio system following the Paramount Decrees of 1948, which broke the monopoly that studios had on owning theatres, the magazines gradually lost two of the gears that had made the gossip industry run: expensive advertising buys and a steady stream of totally free studio-generated publicity and star access, including ready-made features, glamour shots, and an unending supply of young, would-be stars to fill the magazine’s pages.

Previously, the magazines would never deign to cover something as unglamorous as a teen or television star; by 1957, they were covering both, especially when that teen was handsome (Ricky Nelson), sexy (Elvis), or roundly palatable (Dick Clark)

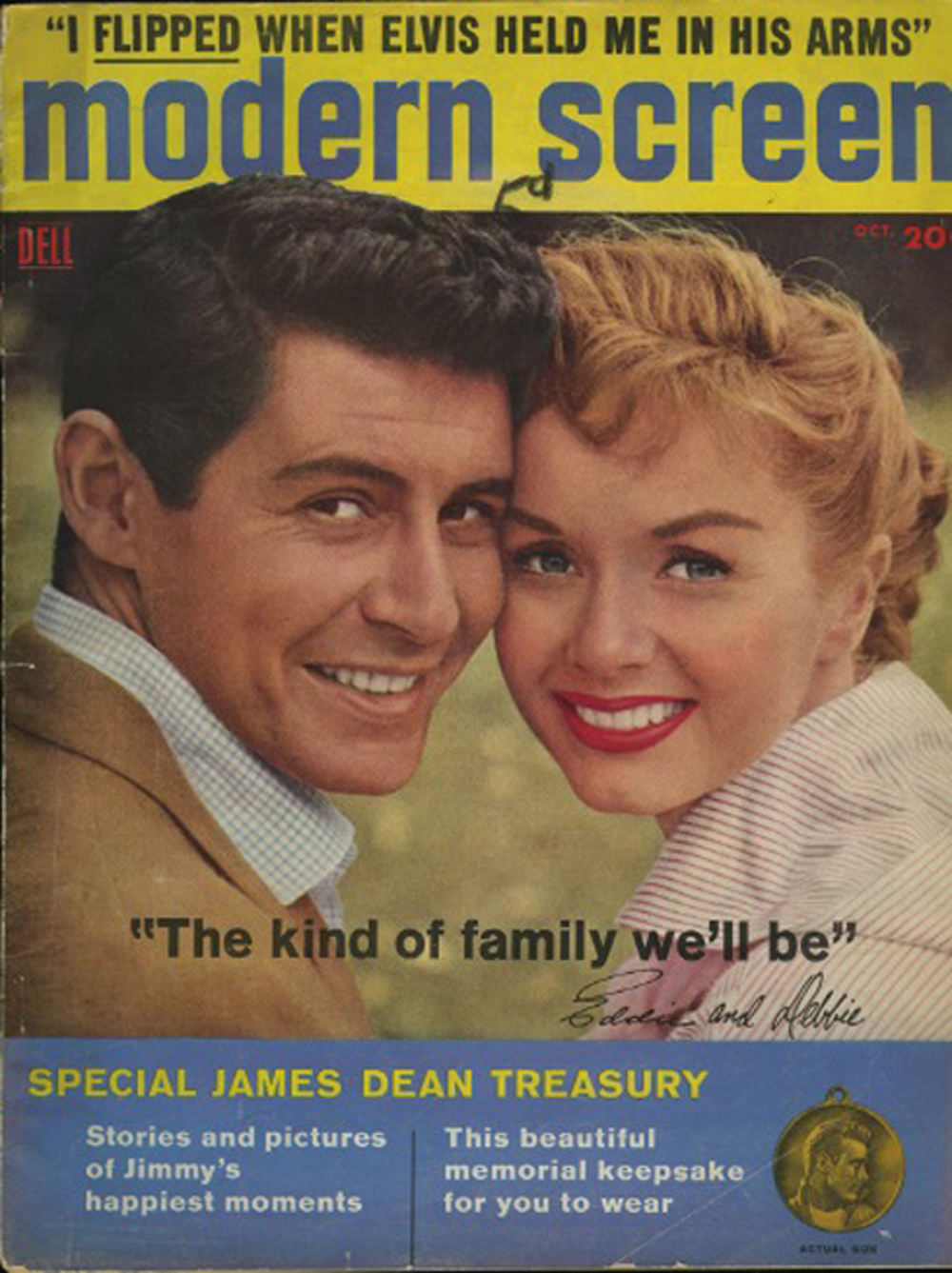

The fan magazine of 1955 had to appeal to the expanding teen market while also maintaining its solid, working- and middle-class, middle-aged readership. They needed to keep the ladies who’d wanted to read advice columns by Claudette Colbert, not learn about some sloppy teenagers. Without James Dean coverage, however, magazines like Photoplay and Modern Screen risked losing the next generation of gossip consumers and their advertising dollars.

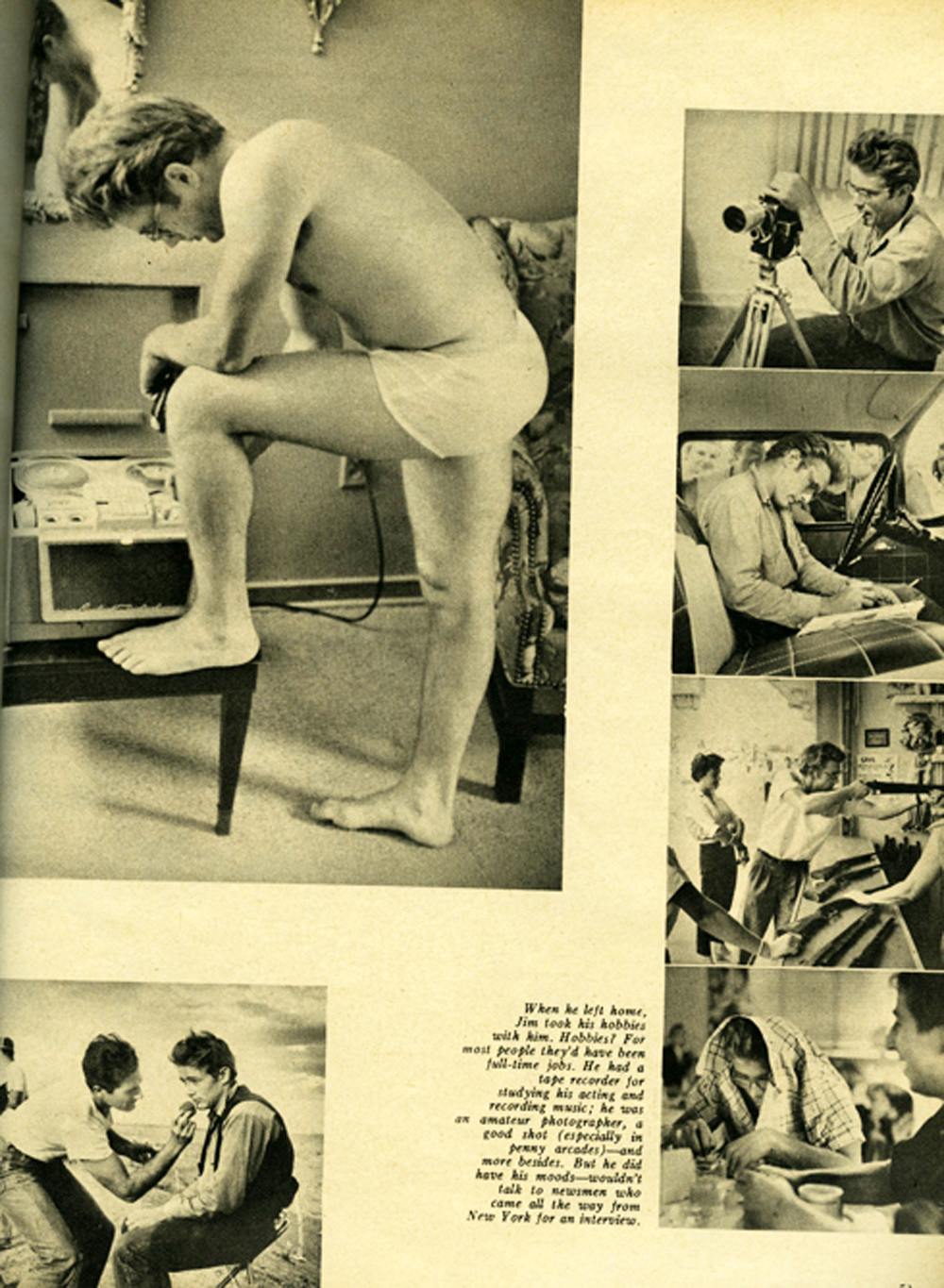

Thus the December 1955 issue of Modern Screen, whose cover promises the details of the chaste wedding of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, but devotes a ten-page spread to Dean’s “Appointment with Death,” an essay by a gossip columnist Mike Connolly that declared “This Was My Friend Jimmy Dean,” and a photo spread that included a shot of Dean in his underwear.

Ten months later, little had changed. The October 1956 cover features a smiling Fisher and Reynolds (“The kind of family we’ll be”) while a panel on the bottom highlights “stories and pictures of Jimmy’s happiest moments” and “this beautiful memorial keepsake for you to wear.”

But the fan magazines had nothing on the one-shots. These single-issue magazines, each focused on one subject, weren’t new at the time of Dean’s death, but they had been growing steadily since the war, covering everyone from Elvis to Billy Graham. Some were a mere penny, others topped out at a thirty-five cents, and the vast majority emerged from well-established publishing companies, such as Fawcett Publications, which was responsible for more than a quarter of the two-hundred one-shots released at the time. One-shots endure today; look at the grocery market check-out aisle and you’ll see special editions of People, Time, even the semi-defunct LIFE, devoted to Kate Middleton or One Direction.

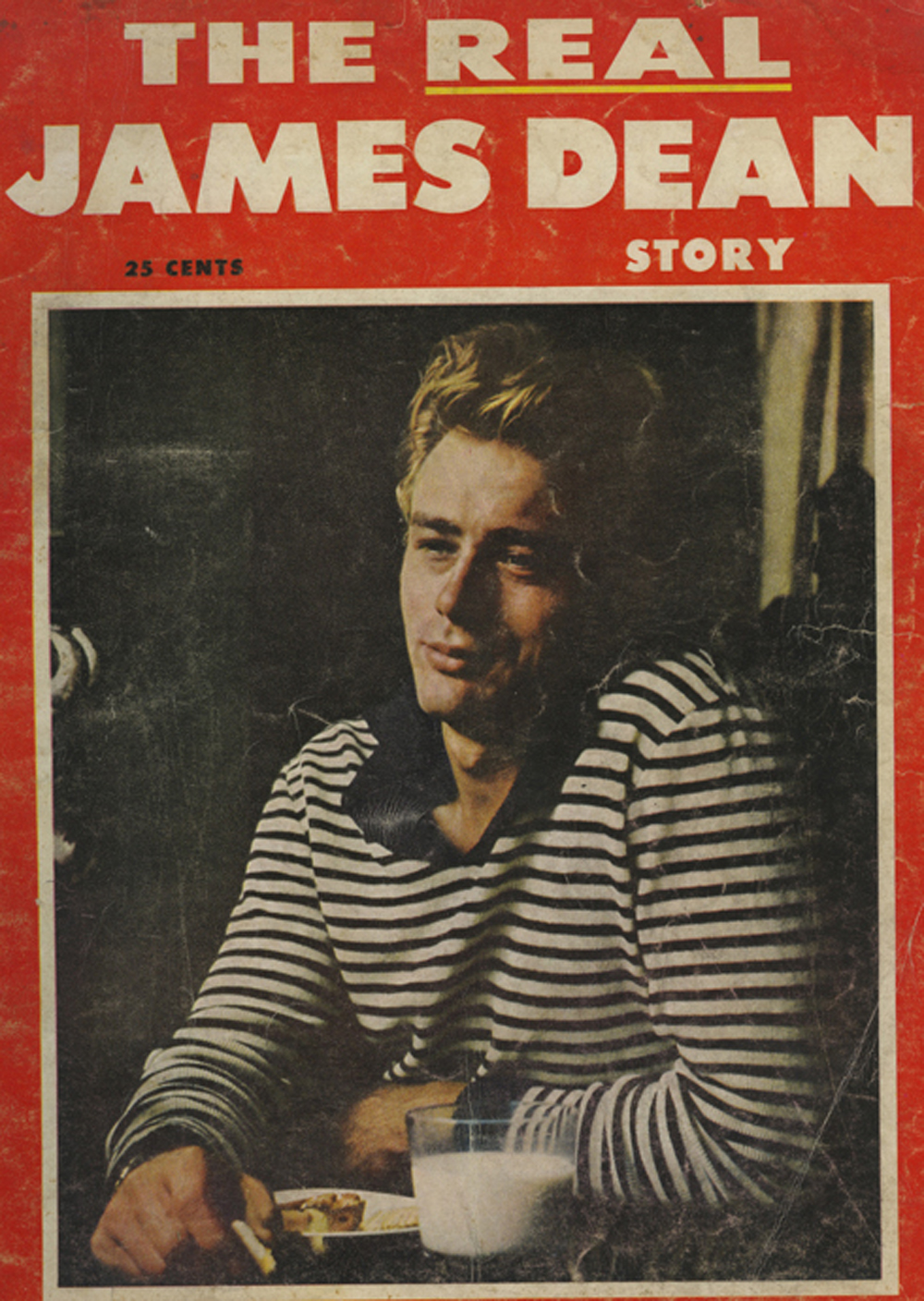

The Real James Dean Story is a one-shot that has the frank, underlined promise of an understanding of Dean, unlike anything you’d previously devoured. Open the first page, and you’re sold: Dean, his shirt unbuttoned, and a table of contents that promises an essay from co-star Sal Mineo, four pages on “The Women in His Life,” and the promise that “Jimmy Dean is Not Dead.” It’s a memorial of relatively high quality, the inside print is vivid and crisp, and they’ve paid for Hedda Hopper’s services, which might not have been as worth as much as they had been in, say, 1945, but remained a mark of legitimacy.Jimmy Dean Returns, however, was something else.

It sold for thirty-five cents more, but the quality is noticeably lower: the paper is pulpier, the photo prints grainer, and the cover is garish in a way that visually connects it to the tabloid and scandal magazines of the time. The premise, however, is perfection: Jimmy Dean returns! But only through the detailed memories of a young girl who supposedly met and loved Dean when she was eighteen years old, and who he warned about his impending death and possible return.

Fan magazines and gossip columnists could generate dozens of stories about a star, even when the life is wholly uneventful: Debbie Reynolds proved as much, as did Doris Day. But those stories are steady filler: nothing lost, nothing gained. If Dean was lightning in a bottle, his death shattered that bottle, and suddenly, everyone was desperate to touch and understand a remnant of him. Teenagers, especially, wanted to map their own ineffable melancholy, their desire to save and be saved, onto Dean. The magazines and one-shots, with their elaborate, purple-prosed renderings of his life, death, and afterlife, provided that opportunity. Each magazine was the same but slightly different; its purchase promised a familiar comfort and a whisper of titillation: what if helived?

The Dean image, and the publishing industry that sprang up around it, was never really about rebellion. It was about sex—unspoken and romantic. Take this fan’s assessment, from a 1956 issue of Coronet:

I hate all the boys compared to Jimmy. I keep looking for him in other boys. He was intelligent and smart. He spoke so softly. I don’t know, he was just perfect, like in his pictures. He wasn’t too tall or too short. He didn’t talk like a hep cat. When you were with Jimmy you knew he was listening to you when he spoke. He was conscious you were there.

It’s remarkably similar to the way teenage girls have talked and continue to talk about a certain type of film idol, ones with beautiful faces and sensitive dispositions—David Cassidy, Davy Jones, Michael Jackson, Ricky Martin, River Phoenix, Johnny Depp Leonardo DiCaprio, Zac Efron, Justin Bieber—who only desire to listen and be listened to in return. It’s still sex, sublimated and sold as poetry.

Which is precisely why young, sexually uninitiated teens like them: sex is terrifying. Brando, who seemed to sweat sex, was terrifying. But Dean offered a means of channeling sexual energy into something far less threatening. Because many, even most, tween girls, whether in 1950 or today, don’t want to actuallyhave sex so much as think about it, and by “think about it” I mean “think about the way he’ll look at you.” The beautiful, often androgynous stars, even closeted stars never forced the issue; they just wanted to hold your hand.

But Dean wasn’t just a poet and a loner in need of love—he was dead. No matter how much you loved him, he would never grow older, never talk about sex, never betray you. The sheer limitedness of his image was part of the charm. Dean died before he was ever truly sexual or menacing, before his persona was even fully formed. And so the vague outlines of his image, frozen in time, will forever bend to accommodate the way yearning but timid teenagers want, and so desperately need, to imagine him.