Woodcut of a woman seated on a obstetrical chair giving birth aided by a midwife, c. 1513. Wellcome Collection.

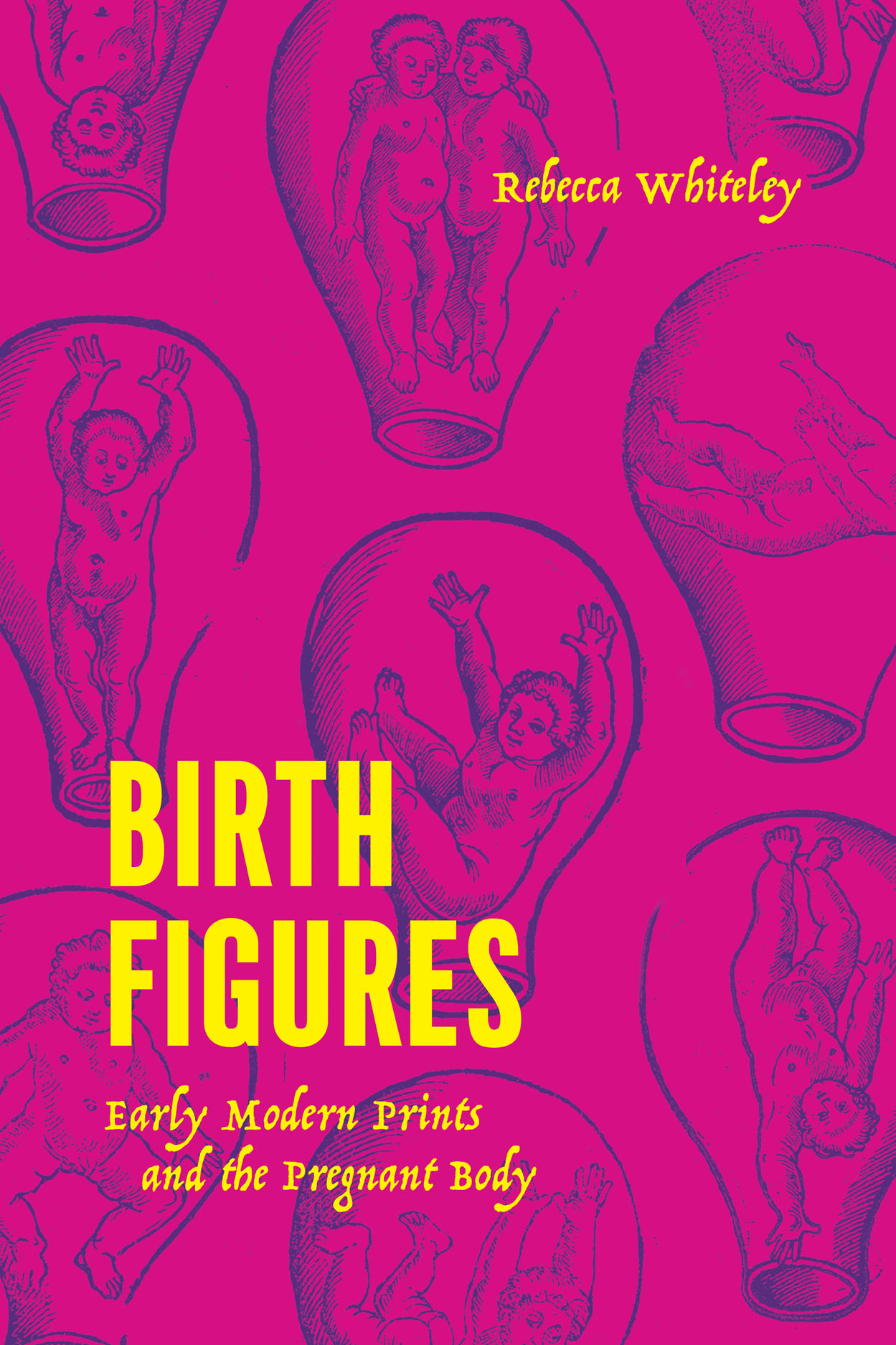

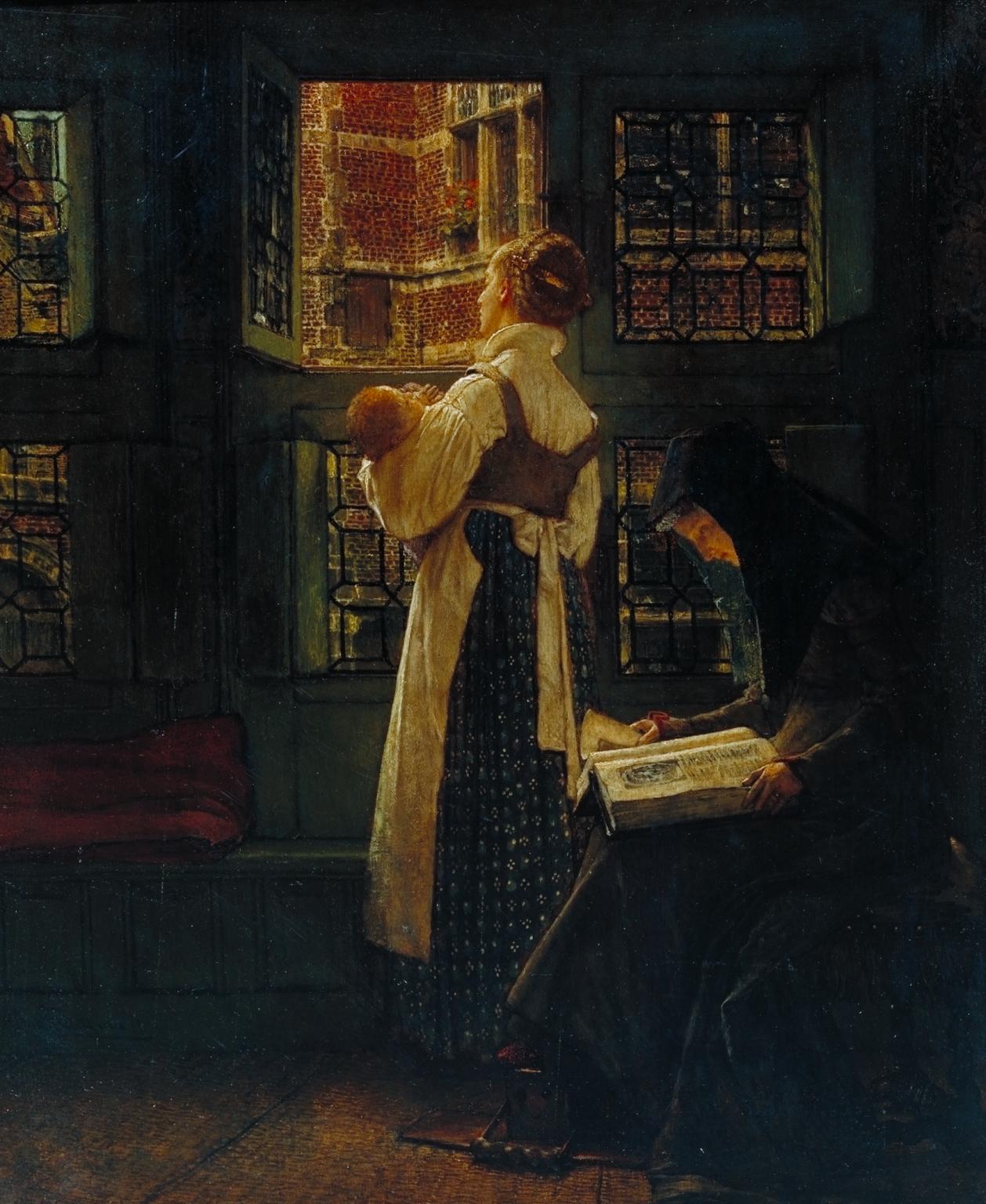

We will begin with a seventeenth-century lying-in chamber in a reasonably wealthy household. We know certain likely features of such a room: that it would be dark and warm, with the windows shuttered and a fire burning. We know it would be filled with women—relatives and neighbors—and well provisioned with linens, medicines, and various foods and drinks for the mother and her gossips. In it, the woman would labor on her feet, on a chair, on her bed, or on the special mattress set up near the fire for the delivery itself. Usually such a room would be presided over by a midwife: a respected local woman with authority derived from experience and practice. She would bring with her certain key items: scissors, a needle and thread, possibly a small knife or a hook, perhaps a special birthing stool or chair.

In such a room, we might also find books, printed or handwritten. Books owned by the laboring woman, or brought by the midwife or one of the other attendants. Books that contained prayers or medical recipes, books that taught the skills of midwifery, and ones that contained birth figures. Little infants, floating and twirling in their wombs, exposed as curious hands opened covers and flicked through pages. These little illustrations proliferated from the mid-sixteenth century and became an increasingly core part of the visual culture of early modern childbirth. They may have been studied in private, pored over by midwives and lay women as well as physicians and surgeons. They may have been shared and discussed in groups of colleagues, families, and gatherings of women. They may have been torn from books and displayed, touched, kissed, even eaten. Print was everywhere and touched everyone’s lives in early modern England and was an inherently physical, interactive medium. Printed images were used and interpreted in multiple ways, manipulated both intellectually and physically. That birth figures had some role in how women experienced and understood pregnancy and childbirth is certain.

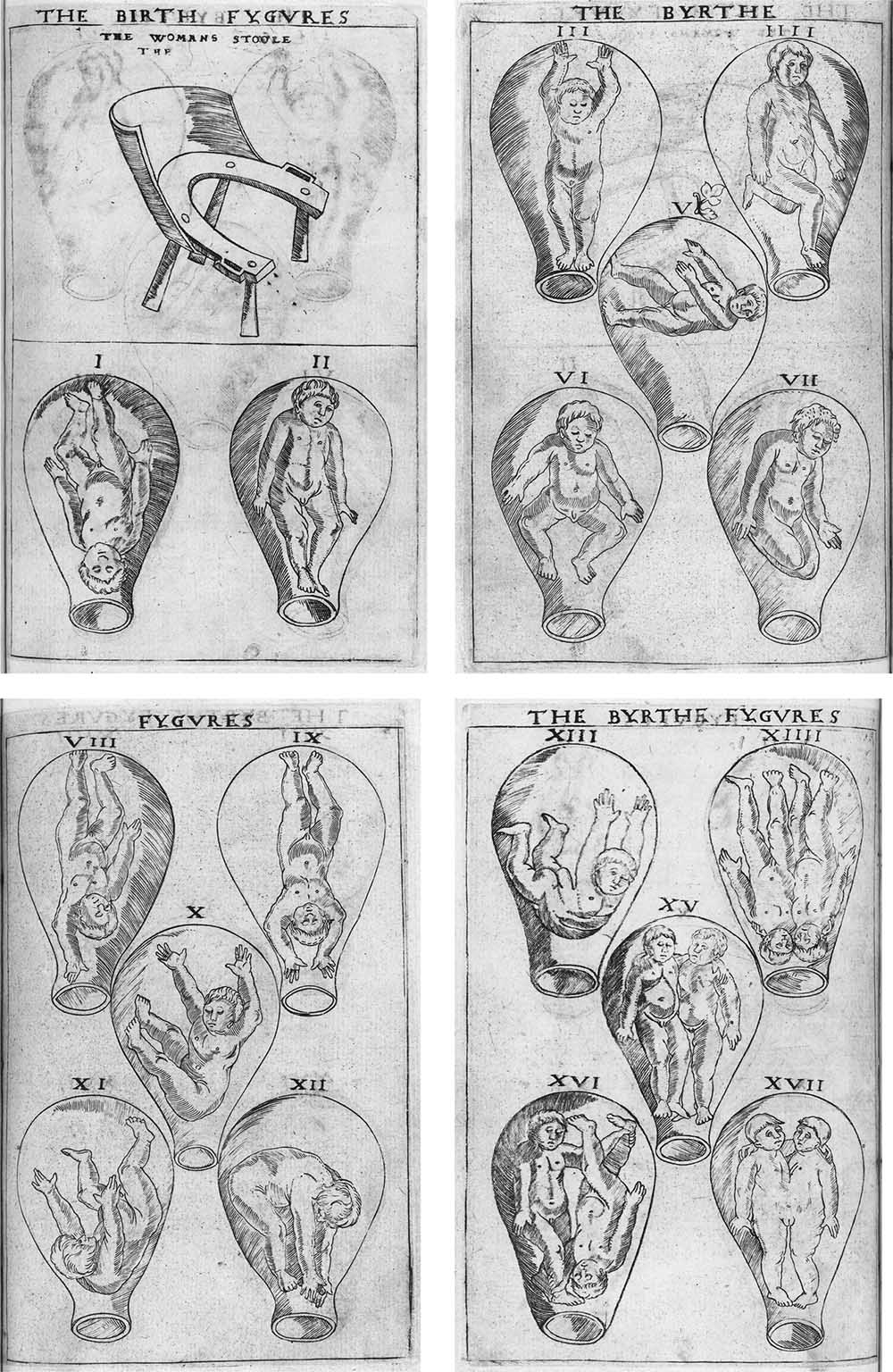

The first printed birth figures in England were produced in 1540, in an English translation of Eucharius Rösslin’s manual of 1513 by Richard Jonas. Retranslated only five years later by Thomas Raynalde, this second translation saw a further twelve editions, the last of which was published in 1654. Rösslin’s Roszengarten birth figures were woodcuts produced by Martin Caldenbach and interspersed with the text. In The Byrth of Mankynde, the illustrations were adapted and collected together into a set of engraved plates. The English copies employ the same simple balloon-shaped and transparent wombs as the German originals, given form by curved hatched lines. The figures are reasonably close copies, though the English versions have a slightly dour look. They grapple both with new subject matter and a new printmaking technique. If, indeed, they were made in England, these plates would be some of the first engravings made in the country. Clearly, the artist still relied on the representational styles of the woodcut, not taking advantage of the fineness of the engraved line or its capacity for crosshatching and stippling to create tone, and thus producing rather sparse images. Yet they would have been wondrous to their first English viewers, offering an unprecedented peek at the mysterious unborn child, using a technique still so new as to hold an aura of mystery and wonder.

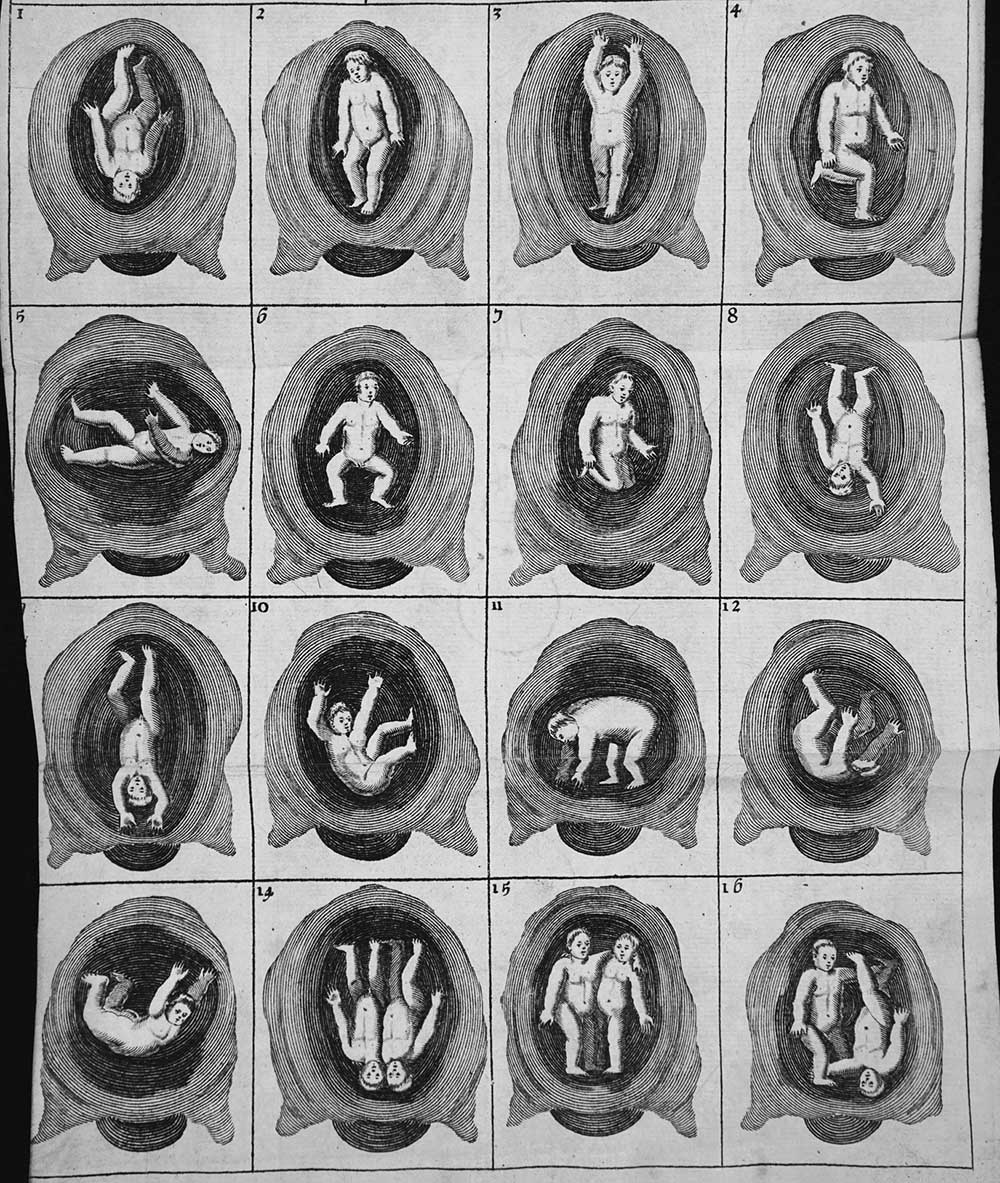

For the rest of the sixteenth-century in England, these figures in The Byrth of Mankynde dominated the visual culture of midwifery, but in the early seventeenth century another set began to ascend. Jakob Rüff published his midwifery manual in both German and Latin editions in 1554 in Switzerland, though like Rösslin’s, his book rapidly spread around Europe. Rüff’s manual wasn’t translated into English until 1637, where it had only limited success as The Expert Midwife. But the birth figures produced for him by Jos Murer have a different story. Like Caldenbach’s figures for Rösslin, these images are small woodcuts interspersed with the text. But unlike Rösslin’s fetuses, here the fetuses are given an anatomical framing: the ovaries and umbilical cord are shown, and instead of being see-through, these uteri have been cut open and the uterine wall and membranes fanned out around the fetus. The fetuses themselves are round-bellied and healthy-looking infants with expressions that vary from smiling, to serious, to suffering. Something about these figures clearly caught the early modern imagination and they were copied and reprinted in numerous books. They first appeared in an English text in 1612, in the English translation of Jacques Guillemeau’s midwifery manual. They appeared in at least a further six titles, including Rüff’s, many of which went through multiple editions.

One final set of birth figures circulated in England before 1672— a single sheet that seems to have originated in William Sermon’s medical and midwifery book The Ladies Companion (1671) and was copied in the third (1676) and subsequent editions of James Cooke’s Mellificium Chirurgiae. These images were clearly influenced by Rüff’s birth figures both in the fetal presentations and in the way the womb seems to have been cut open and folded back. However, the vortex-like concentric lines employed to describe the womb distinguish these from the more direct copies.

Despite their ubiquity, birth figures have received little scholarly attention, and even less that is not openly dismissive. In order to properly assess the significance of birth figures in early modern culture, several historic assumptions must be reassessed. Older schools of medical history have tended to denigrate birth figures as anatomically inaccurate and representationally naïve. Conversely, some feminist histories of midwifery have dismissed them as part of an elite male and medical culture that had no bearing on women’s midwifery practice. Academic Wendy Arons has even argued that the images and text of midwifery manuals, where they were seen by women, may have degraded their practice.

So on the one hand we have the masculine, teleological histories of obstetrical progress that valorized medical discovery over patient care and credited, overtly or tacitly, the male medical rhetoric of female inferiority. On the other we have feminist histories of midwifery, which tended to present female practice in an idealized light, as forming a harmonious and empowering female community of effective but completely nontextual and nonmasculine practice. These early feminist histories were an absolutely necessary antidote to earlier, overtly misogynist medical histories, but they have left us with a dichotomy in thinking about “manmidwifery” that historian Lisa Forman Cody has aptly described as “medical glory versus gory misogyny.” However, in more recent decades, scholarship has come to recognize not only the difficulties and problems of both men’s and women’s midwifery practice, but also the ways in which they influenced and integrated with each other.

Midwifery in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England should be understood as diverse, changing, and working along spectra, rather than strict divisions. Women with no formal medical training still delivered the vast majority of women, but surgeons and physicians were increasingly present in the lying-in chamber, called in during emergencies, or simply monitoring the progress of wealthier women’s labors. Male medical practitioners learned skills from midwives, and midwives gained medical and anatomical training from men. Family businesses often included male surgeons and women midwives working in tandem. Later textual vitriol against women midwives by male authors has left us with a feeling that men and women must always have been at war over midwifery. But it is most likely that, in most cases, occasional differences and struggles for authority and credit were balanced by pragmatic relationships of respect and collaboration.

This model extends to midwifery manuals: while largely written by men and derived from medieval gynecological manuscripts, they were also increasingly influenced by contemporary knowledge gleaned from midwives. Moreover, it is clear that book learning became an increasingly desirable attribute for women midwives, as they incorporated some learned medical knowledge in order to improve their practice and their social standing. Historian Monica Green has argued that in the medieval period, gynecological and obstetrical texts were largely made for and by men, and while women were in charge of delivering babies, “midwifery” as a profession was not widely recognized. What we see happen slowly, from the late-medieval to the modern period, is the engulfing of childbirth by medicine. This does not mean, however, that male medical obstetrics destroyed female midwifery. Rather, the role of the woman midwife arose alongside and tied to that of the male surgeon and physician, as a marginalized, limited, oft-denigrated medical profession. Books written by men were, therefore, crucial to midwifery as it was practiced by women in the early modern period.

In England, it is important to note, the male doctor never actually displaced the woman midwife, nor did the medical establishment wish to do away with women’s practice. They simply wished to control it by taking it into the fold of medicine and defining its remit, and midwifery manuals played their part in this. We must understand midwifery manuals, therefore, not along gender lines, as representations of masculine medicine, but as influenced and used by both men and women, though they contributed to a medical culture in which men held much of the power. Yet scholars have tended to cast doubt on the extent to which women midwives actually read midwifery manuals, citing not only the divide between learned medical and empirical knowledge, but also low literacy rates among early modern women. It is worth, therefore, looking in more detail at the evidence for and against female readerships for midwifery manuals.

While it is true that women were on the whole less likely than men to be literate and to be book owners, literacy rates rose steadily for both genders from the sixteenth century onward. Scholar Adrian Wilson, moreover, has shown that literacy rates were particularly high among midwives, and that most midwives, even those operating in poor and rural areas, could read by the mid-seventeenth century. Evidence from the books themselves suggests that women were reading them. Many texts addressed themselves to women readers, and particularly to women midwives. Some, such as Jonas’ translation of Rösslin, also attempted to discourage certain types of male reader—namely, the uneducated and the young. There was a general feeling that the knowledge contained in midwifery manuals belonged, to a certain extent, to women, though it was of course mediated and controlled by learned men. Moreover, the sheer number of midwifery texts available in the seventeenth century means that women must have regularly encountered them. Considering that best-sellers such as Nicholas Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives went through at least twenty editions between 1651 and 1777, and that single books in this period often had multiple owners and were used over long periods of time, it seems likely that midwifery manuals were a source of body knowledge that spanned many spheres of society, male and female, rich and poor, lettered and unlettered.

There is, moreover, direct evidence of at least some women readers in the form of inscriptions. Given that women were less likely to own the books they read, and to be able to write in them even if they did, the existence of these inscriptions by women readers indicates a much larger number who owned and read but did not mark, or who read or even heard without owning. Some inscriptions seem to defy the silencing of women readers, as in one manual, described by William Sherman, inscribed “Elizabeth Hunt her Booke not his.” Other women owners were more circumspect. In a 1682 copy of James Wolveridge’s The English Midwife Enlarged, held at the Huntington Library, the owner, Mary Hillyer, wrote:

Mary Hillyer her book

god give her grace ther

unto look not to look but

to understand larn [learning] is beter

then house or land

July ye 2 1790

Another inscription, in a 1662 edition of W.M.’s The Queens Closet Opened, a recipe book including remedies for problems associated with pregnancy, birth, and nursing, held at the Wellcome Library, reads, “Mary Busby/ no Great Physitian.” In different ways, these women use inscriptions to situate their own identities as readers. With humility they acknowledge their distance from the masculine world of learned medicine, but at the same time they shape their position as women who access both masculine medical knowledge and traditional feminine knowledge.

Evidence from the manuals themselves indicates that over this period it became increasingly important for midwives to be familiar with the literature. By offering works that combined and condensed the wider literature on midwifery, many authors both emphasized the necessity of such knowledge and made it attainable for midwives who might afford one manual but would never amass a large and multilingual medical library. Jane Sharp, in her manual of 1671 for instance, promised that she was “at Great Cost in Translations for all Books, either French, Dutch, or Italian of this kind. All which I offer with my own Experience.”

We can, unfortunately, put no great stress on the fact that Jane Sharp herself was a woman author and reader of midwifery manuals, as the jury is still out on whether she was a real person or a pseudonym for a male author. I cannot, however, agree with historian Katharine Phelps Walsh that the lack of a strong personal narrative of experience (as later women authors Sarah Stone and Elizabeth Nihell would provide) indicates that the book was not written by a woman. Indeed, were a woman to write a manual in this period, it would be a logical decision to acquire authority by adopting the style and form of writing developed by men, who had little direct experience of childbirth. Indeed, it is only after male authors had begun to place emphasis on their empirical experiences of childbirth that women writers too began to recount their experiences in published texts. Moreover, even if Sharp is a pseudonym, it is worth noting that a man felt his book would gain legitimacy by being authored by a woman. That this would have been a plausible and profitable lie suggests that women midwives did engage with textual culture, even if they left few traces of it.

Even for those women who could not read, the midwifery manual was likely still an accessible text. Then, as now, a song or a story, an expression or a piece of news, could migrate promiscuously between these three vehicles of transmission as it circulated around the country, throughout society and over time.” The ubiquity of reading aloud, as well as retelling things read, meant that everyone was engaging with print culture in some way. It is easy to see how this textual knowledge would have fitted into existing communities of women who shared recipes and advice, watched each other’s conduct, and regularly assessed, and recommended or denounced, medical practitioners. Other readers, as has been widely noted, sought out midwifery manuals not as medical textbooks but as sex manuals, or as erotica.

Adapted with permission from Birth Figures: Early Modern Prints and the Pregnant Body by Rebecca Whiteley, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2023 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.