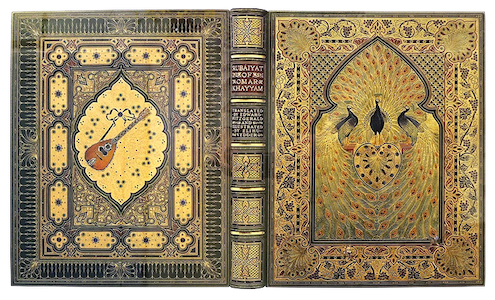

Treasure bindings

As early as the sixth century European monks would bind their most prized illuminated manuscripts in wooden boards decorated with jewels and precious metals. Many of these bindings were later looted for their valuable gold and stones. Treasure bindings saw a small renaissance in the early twentieth century. The British bindery Sangorski & Sutcliffe, known for ornate and expensive work, bound a copy of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám in tooled leather covered in three peacocks made of over one thousand jewels set in gold. Known as the “Great Omar,” the book is at the bottom of the ocean—it went down on the Titanic. The bookbinders created two other versions, one of which was destroyed in World War II; the other is housed in the British Library.

Bamboo and lacquer

Thai palm-leaf manuscripts were often covered in intricately carved bamboo or sometimes ivory boards. Bamboo covers were frequently lacquered in red or black to protect the book and also to provide a surface for further decoration. Some lacquered covers were inlaid with mother-of-pearl or embellished with gold leaf or gold paint; others had leaves or flowers carved into the lacquer. Bound manuscripts were then often wrapped in cloth wrappers or pouches to protect the covers.

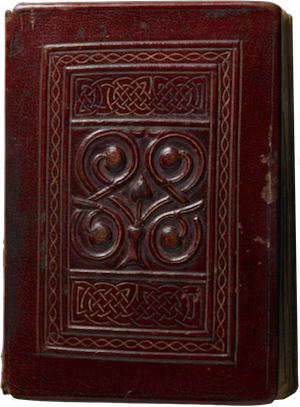

Leather

Most books in medieval Europe were bound in leather. The oldest intact (still in its original binding) European book is the early eighth-century St. Cuthbert Gospel, a manuscript of the Gospel of John that was buried with Saint Cuthbert and rediscovered when his remains were moved in the twelfth century. Its cover is made of ornately tooled red leather over wooden boards. Less valuable or common books would sometimes be bound in parchment or vellum, or even used scraps, and usually left undecorated. The parchment either covered wooden boards or was folded on itself to create what’s known as a limp binding.

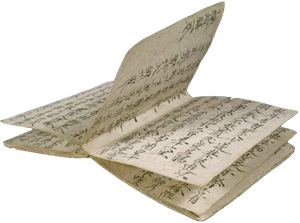

Butterfly bindings

A butterfly binding is one of the most common traditional Chinese binding techniques: sheets of paper are folded in half and pasted together at the folded edge to form a spine. Butterfly bindings allowed for better portability than scrolls and also had more room for text. This style traces back to the tenth century—butterfly books have been found at the archaeological site of the Silk Road town Dunhuang—and was used for both manuscripts and printed books. Printed butterfly books left the sheets blank on one side, so that a two-page spread of printed leaves alternated with one of blank leaves. Because the sheets were printed and then folded for binding, a single wood block could be used to print both pages at once.

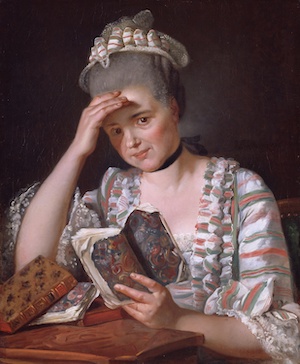

Paper

In the eighteenth century many books were sold in paper wrappers or in paper-covered boards—temporary bindings that book buyers could replace with whatever style of bindings they wished (booksellers and binderies offered a range at different price points). But binding was expensive, and many people never re-bound the books they purchased. Jacques-Louis David’s 1769 painting Madame François Buron shows Buron reading a book bound in the marbled paper of a temporary wrapper. Inexpensive ephemeral literature bound in paper—such as British chapbooks, the French bibliothèque bleue, and American dime novels—are different from the books bound in paper wrappers, because their bindings were intended to be permanent.

Cloth

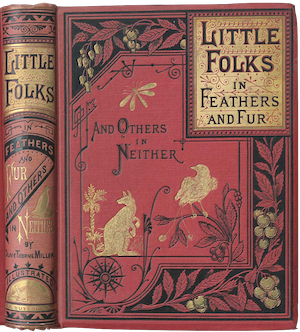

While some manuscript books were bound in cloth, in Western book manufacturing cloth bindings became much more common in the era of printed books, especially during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as book publishing grew. Publishers wanted to sell their books in permanent bindings but also wanted a cheaper method and material than leather. They opted for cloth case bindings, where the binding is made separately from the printed book and then attached. Usually cloth bindings covered boards made of wood or thick paperboard; the earliest examples were plain cloth with a leather or paper label. In the 1830s binderies developed techniques to emboss cloth covers with gold decoration, although initially the ornament tended to be limited to a gilt title on the book’s spine.

Publisher’s bindings

Before the 1840s most of the decorations on publisher’s book covers were generic—a title might be surrounded by gilded laurel, which didn’t tell a buyer anything in particular about the book. As illustrated books became increasingly common, book manufacturers began embossing their covers with adaptations from the book’s interior illustrations, creating covers that were unique to each title and that served to advertise its contents. Over the next fifty years, manufacturers began to add color lithograph insets to book covers and use colored inks to create increasingly ornate designs, getting closer and closer to something like the modern designed book cover. In this period book buyers were still sometimes offered a choice of binding, paying a premium for tooled leather or full-gilt cloth over plain cloth. A reader could buy an 1856 edition of Frances Percival’s Sweet Home bound in cloth for a dollar but would have to pay an extra $0.25 or $0.75 for gilt cloth or leather, respectively. In the early twentieth century highly decorated cloth covers were increasingly replaced with printed paper dust jackets that covered a plain cloth binding, much like today’s hardcover books.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.