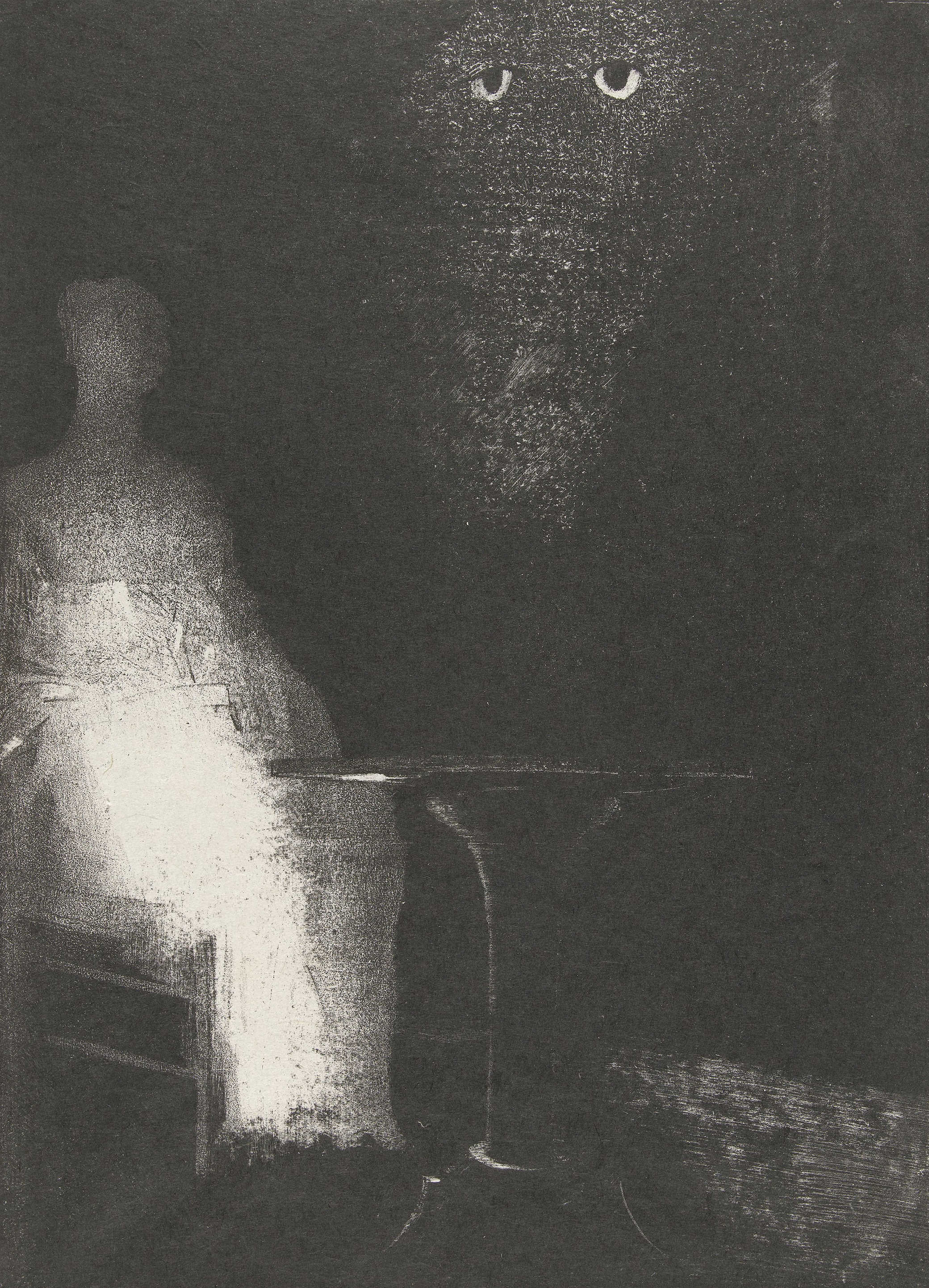

I Watch from Above in the Vague Form of a Human Figure, by Odilon Redon, 1896. Rijksmuseum.

In 1965 the San Francisco band the Warlocks needed a new name after learning another band was already using theirs. Their guitarist, Jerry Garcia, the legend goes, opened the 1955 edition of The Funk and Wagnalls New Practical Standard Dictionary, Britannica World Language Edition to a random page and launched his finger at an entry. He landed on “The Grateful Dead,” and what came next, as they say, is history.

What came before is also history. What was this preexisting “Grateful Dead” that had already earned an entry in the dictionary?

The term that Garcia landed on referred to a specific genre of folklore. The structure of a “grateful dead” tale is easy to follow, best captured in a story Cicero recounts in On Divination, first published in 44 bc. The poet Simonides, Cicero writes, “once saw the dead body of some unknown man lying exposed and buried it. Later, when he had it in mind to go onboard a ship, he was warned in a vision by the person he had buried not to do so and that if he did he would perish in a shipwreck. Therefore he turned back and all the others who sailed were lost.”

A more fleshed-out version of the story appears in the late thirteenth-century romance Richars li biaus (Richard the Handsome), which tells the story of the eponymous wandering knight. Setting off through a foreign land in pursuit of glory, Richars wastes so much of his father’s money that he can’t enter a tournament for the hand of a maiden. A benefactor gives him a horse, attendants, and some gold to compete, but en route he spends part of his money giving a great feast at a city in Austria. At the feast he is astonished to discover a corpse suspended from the beams and is told that the dead man owed the lord of the house a great sum of money. Richars gives away everything he has, including his armor, to pay the debt and bury the man. With no means to compete in the tournament, he wanders hopelessly. He then meets a mysterious White Knight who provides Richars with a new set of armor and a better horse. Richars wins the tournament, and then offers the White Knight either the hand of the maiden or the property won. The White Knight refuses both, reveals himself to be the ghost of the indebted man, and disappears.

The plot element was well known to nineteenth-century folklorists, but the stories featuring this arc weren’t examined together until the folklorist Gordon Hall Gerould published his 1908 book The Grateful Dead: The History of a Folk Story. Gerould found evidence of the Grateful Dead story in folklore and myth from Siberia to Spain and from Iceland to Armenia. The narrative is so old and widespread that it was almost impossible to divine its origins—yet until Gerould’s book, no one had thought to bring them together for study. “The combination of narrative themes is so frequent a phenomenon in folk and formal literature,” he wrote at the time, “that one almost forgets to wonder at it.”

The Grateful Dead, at its essence, is nothing more than this: a traveler comes across a corpse, unburied, and endeavors to give it a proper burial. Some time later, the traveler meets a stranger who offers a form of aid, and who subsequently is revealed to be the ghost of the dead man. Cicero’s story offers its most essential elements, but in most versions of the story the reason the body hasn’t been buried in the first place is due to the deceased having unpaid debts. There is a story out of Lithuania in which a king pays his last fortune to bury a dead man and in doing so is forced to become a merchant, traveling the seas to regain his wealth. He rescues a princess and marries her. The princess’ father doesn’t approve, of course, and sends a messenger to take the couple on a voyage; at sea, the messenger throws the former king overboard, but he’s saved by a man in a boat who reveals himself to be the dead man. In the Irish folktale “Beauty of the World,” it is a king’s son who discovers a church where four men are arguing over a body. The dead man owed two of the men five pounds, and they refuse to release it to the man’s sons unless they pay; they don’t have the money, so it is the king’s son who pays the debt. Subsequently, a red-haired stranger appears and, through a series of trickster-like machinations, helps the king’s son win the hand of a woman before revealing himself to be the ghost of the dead man. In one Norwegian variant, an executed man has been frozen in a block of ice on display outside the tavern for villagers to spit on; the young man who frees and buries the corpse later meets a helper who similarly repays his generosity.

Burial is such a fundamental rite that, even for a folktale, it’s shocking to suggest it might be denied simply for unpaid debts. But the Grateful Dead story, repurposed so many times across cultures and time periods, is rarely set in the land where it is told. Instead, the Grateful Dead always live somewhere else. The tale seems to announce that it is a narrative born not in reality but in fear of what might happen elsewhere, across borders during a disaster or period of decay.

Stories that involve the Grateful Dead motif often send the protagonist on a journey or quest that will lead them to a new and unusual place, where normal customs are not observed. As with cannibalism, refusing burial simply for unpaid debts is seen as abhorrent and against basic human decency, which is why it’s projected onto a foreign land; the story can remind the reader how much superior one’s own culture is. There’s something barbaric about this practice, in the sense of the literal definition of “barbarians” as the uncultured, uncivilized foreigners just beyond the borders.

Herodotus, for example, writes that during the reign of Asychis in the tenth century bc, “an Egyptian could get a loan by declaring his father’s corpse as security. Appended to this law was the stipulation that the creditor could assume possession of the whole grave site of the debtor as well, and added to this, a penalty was imposed also upon anyone who pledged this kind of security but who was unwilling to pay his debt, that when he died, he would have no grave in the burial place of his ancestors nor any other grave; and his descendants could not be buried either.” Herodotus’ report has never been substantiated by modern scholarship, but it would fit a pattern of treating non-Greeks as subtly barbarous, unsympathetic to the high importance the Greeks gave to burial. (The first ghost that Odysseus encounters in the underworld is his crewmember Elpenor, who died on Circe’s island and was never buried: “Do not go on and leave me there unburied, abandoned, without tears of lamentation,” he tells Odysseus, “or you will make the gods enraged at you.”) It’s highly ironic to accuse the Egyptians, of all people, of indifference toward the corpse, but the insinuation that they would forgo this basic rite in favor of commerce would signal to Herodotus’ audience that they were superior to this barbaric race.

In a Jewish version of the Grateful Dead story, a young man is in Istanbul, on his way to Jerusalem, when he finds the corpse of a Jewish man hanging from the gallows. Making inquiries, he learns that the man was accused of being a thief and of having stolen from the sultan, and further, that the sultan has commanded the body be left there until the Jews of the city repay the sum the condemned man supposedly stole. He will also eventually be saved and rewarded by this hanged man’s spirit, but the collective-punishment element here is a reminder of how such stories could be used to build a communal identity, and how a shared obligation to bury the dead could further reinforce that.

The story of the Grateful Dead endured for so long, through so many different cultures, because it involves two central aspects of human culture: burial rites and debt. It reminds us that we are indebted to the dead, and that through burial, the dead become indebted to us. Not just the dead of our own families; we are reminded of an obligation that goes beyond just taking care of our own. Above all, that reciprocal relationship trumps the world of financial debt. It is a story about higher- and lower-order obligations, one that reminds us which comes first.

Or does it? As capitalism took hold in Europe, calculations as to what we owed the dead and what we owed the market began to change. By the Middle Ages, it seems, this concept of refusing burial for debt had become much less foreign. In England, in the years leading up to the Reformation, the clergy had embraced a practice known as mortuaries: payments made by grieving families to the priest who performed a loved one’s last rites. Initially this practice had been voluntary, a token gift of gratitude or thanks, but as corruption seeped into the Church, mortuaries became customary and then obligatory, with the result being that a priest might refuse last rites without payment.

Complicated economies were developing everywhere around burial. In France those in debt could be excommunicated, and if they died still in arrears they could be denied burial in consecrated ground. Historian Tyler Lange’s book Excommunication for Debt in Late Medieval France: The Business of Salvation tracks the rise and fall of this practice, noting that it accelerated in the fourteenth century and had declined by the seventeenth. Lange describes how toward the end of Lent each year, there was a flurry of excommunications and absolutions of debtors—the excommunications as their creditors demanded their due, and their absolutions as they repaid those debts or the creditors prevailed on them the importance of charity.

While this practice would seem completely antithetical to basic tenets of Christian charity, Lange suggests that, for medieval France, excommunication for debt “could in fact be seen to fulfill the pastoral and Christian imperative to encourage charity and concord within Christ’s body.” Like blood circulates through a body, credit needed to circulate through the community in order for it to function effectively—such exchange of debt and credit brought the community together, bound people in ties that went beyond family or strict self-interest, and encouraged the further circulation of goods and services. Excommunication for debt, Lange suggests, urged debtors to pay back their loans and reenter the economic community; for creditors, forgiving debts that couldn’t be repaid became a matter not just of financial charity but of saving someone’s immortal soul.

The traveler paying the dead man’s debts, then, is not performing a basic act of mercy so much as restoring the dead man’s credit back into circulation. The message of Richars li biaus is that the knight’s profligate spending is not entirely immoral: by immoderately spending his last coin on the dead man’s burial, he not only returns the dead back into the fold of common humanity but earns substantial returns on his initial investment. If the failure to pay one’s debts excommunicates one to the outside of society, then the largesse of the young man brings the dead man back in, allowing him—like his unpaid capital—to recirculate in the community and the economy once more. Rather than prioritizing burial rites over financial obligations, perhaps, these stories function rather to bring them together, to create an equivalence between one’s physical body and one’s financial body.

The malleability of the Grateful Dead story allows it, paradoxically, to both condemn a culture that allows the dead to go unburied for debt while also encouraging such an exchange, one in which the dead and the living invest in each other across a seemingly impassable divide.

But even something so malleable has a shelf life. The folklorist Heidi Anne Heiner, in her 2015 introduction to a new edition of The Grateful Dead: The History of a Folk Story, notes that in the century since Gerould’s book was first published, the Grateful Dead story itself has fallen from popular consciousness, known now only to folklorists and hippies. It has not, as have so many other folktales, been made into a children’s animated film, nor otherwise been reintroduced into pop culture through contemporary narratives.

Part of the problem with the Grateful Dead cycle is that there’s no single, easily recognized story that everyone knows, no central character like Cinderella or the Frog Prince. Instead, it appears as a plot element (and sometimes only a minor plot element) in hundreds of stories, many of whose popularity has generally waned.

One of the few modern cinematic usages to bear vestiges of the Grateful Dead theme can be found in 2002’s The Ring (and the original 1998 Japanese film, Ringu), where Naomi Watts’ Rachel Keller finally learns that the spirit haunting her and her son is an abused child named Samara who was denied a proper burial. After discovering Samara’s corpse and laying her to rest, Keller believes she’s free of the ghost. Only, as the film’s final twist reveals, this act of charity is insufficient, since Samara is pure evil. The modern dead, it seems, aren’t indebted, nor are they feeling all that grateful.

Heiner suggests that some of the folk cycle’s core elements have metamorphosed into another story, the “Vanishing Hitchhiker,” after which Jan Harold Brunvand named his classic 1981 book on urban legends. In the Vanishing Hitchhiker story, a traveler stops to pick up someone on a desolate stretch of road; as long as the driver behaves cordially, at some point the hitchhiker will disappear. The driver will later learn of a tragedy in that spot on the road, and the suggestion that the hitchhiker was a ghost. If you’re scared of or hostile toward the ghostly hitchhiker, it may curse you; conversely, if you’re respectful, it may offer you aid or advice down the road. Which is why, Heiner suggests, it’s a natural evolution of the Grateful Dead story.

But what’s missing from this variation is gratitude for the act of burial itself: the ride is the only favor offered the dead. The original premise of the Grateful Dead story, that a corpse would lay unburied for unpaid debts, seems so anachronistic and odd, that the entire cycle seems to have receded, something from the past that has no place in our contemporary society.

But perhaps this story will bear new meaning for us soon enough. For decades, modern societies have worked to remove the unpleasant from sight, to whisk away dead bodies so we don’t have to look at them. It has been a long time since we have corpses rotting in the streets for lack of burial. But in a new and terrifying landscape, where bodies are stacked in refrigerator trucks outside of hospitals and stashed away in nursing home storage closets, we again need to be reminded of what it means to care for a stranger’s body and to see that it receives a proper burial.

Such stark and unsettling images only reinforce a more discomfiting truth, that even before this current pandemic, the need for such mercies was everywhere around us. A search on GoFundMe for “funeral expenses” reveals, as of this writing, 1,335,875 different campaigns (and climbing), all raising money to bury loved ones or retire the debt incurred in funeral costs. The need for a stranger to cover expenses to bury the dead has become so frequent a phenomenon that one almost forgets to wonder at it.