Unfinished Sketch of Lady Haden, by James McNeill Whistler, 1895. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

In 2014 data-mining whiz Adrianne Wadewitz embarked on a rock-climbing trip in California that proved fatal. Tributes to Wadewitz—a sharp, bespectacled, piano-playing redhead—soon followed in Buzzfeed, the New York Times, and other publications. The scholar and self-described digital humanist was known for creating Wikipedia articles about women like Mary Wollstonecraft and for organizing edit-a-thons to seek more gender parity on the online encyclopedia, whose volunteer editors have long been disproportionately male. She recruited veterans and newcomers to add personal details, footnotes, and accomplishments to biographical entries of women. Among her nearly fifty thousand edits was a change to a plot point from an eighteenth-century novella. A Wikipedian had described a sex scene as consensual, depicting a heroine who “succumbs to her desires.” Wadewitz edited the page and called it “rape.”

Our current moment of worldwide reckoning, in which women are demanding justice for sexual harassment across every industry, sometimes regards female outspokenness as something new. But what about the centuries of women who came before us, intellectuals and makers and civil rights crusaders and resistors far more complicated than we can even imagine, who were written out of history?

The year of Wadewitz’s death, writer Amanda Hess criticized the New York Times for ignoring women in its obituary pages. When a lesser-known woman has been memorialized in the paper in the years since, it ricochets across social media. Frances Gabe, inventor of the self-cleaning house? Sheila Michaels, who popularized the honorific Ms.? Naomi Parker Fraley, the “real Rosie the Riveter”? The past century has, through retiring obituary writer Margalit Fox’s stories, given us many remarkable women, even if they aren’t remembered at the same rate as their male counterparts.

Cue “Overlooked,” a project launched in spring 2018 to give dead women their retroactive due at the Times—featuring one entry by Hess. Among the first-time obituary subjects are novelist Charlotte Brontë and Bollywood legend Madhubala.

As the national conversation on race and gender escalated, the Times’ new digital editor Amisha Padnani says, “It all kind of had me thinking: as a woman, and as a woman of color, what can I do to help diversify our pages?” She had been researching Mary Ewing Outerbridge, who brought tennis to America in 1874, and couldn’t find an archived obituary. It wasn’t the only time an obit was absent from the archives. “My list just got longer,” Padnani says. She eventually penned an overdue obituary for Outerbridge.

“I can’t say why a news editor decided it wasn’t important enough to do an obituary on Sylvia Plath back in the day,” Padnani says. “I know now we would absolutely do one, and we wouldn’t even question it.”

Unearthing female history—from culinary to architectural to literary—has become quite the undertaking for contemporary women on the internet.

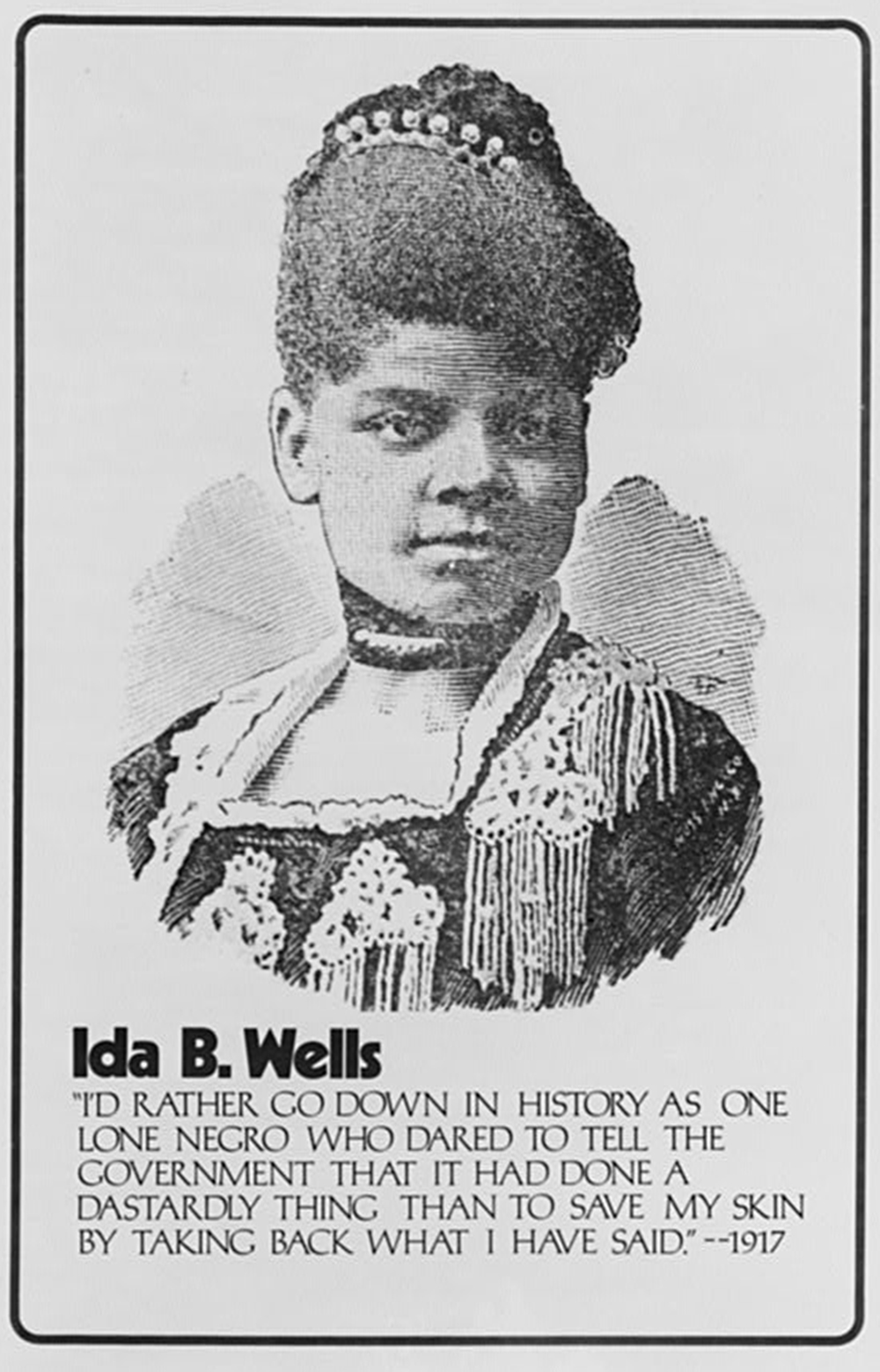

On the Facebook page for lifestyle brand Refinery 29, a sketch of Cynisca of Sparta, the first woman to win the Olympics in 392 (and be barred from the ceremony), has drawn likes, hearts, and a few wows. Another post featured Ida B. Wells, the American civil rights activist, suffragist, and journalist whose reporting on lynching in southern states gained international attention. The first female-authored feminist manifesto, according to another post, was written by Marie-Madeleine Jodi during the French Revolution. It envisioned a female-led legislature and court system.

Behind these posts is the New School’s Gina Walker, a professor of women’s studies who directs The New Historia, a project that seeks to recirculate the lives of forgotten women. The digital repository is designed for an audience programmed to think in 140 characters.

Witnessing these women online, their stories packaged for modern audiences, is still a novelty. University-level women’s studies courses are only forty years old, and the standard American education curriculum still misrepresents or underrepresents women’s contributions. “It’s this larger perspective within which everything, including #MeToo, wants to be seen,” Walker says. “Until women understand and acknowledge how little they know about being female, I think it’s just going to perpetuate the way we’ve been in the world for millennia.”

You need not turn back centuries to track the erasure of women in public memory. It works cyclically, in spans of decades or years.

There is a living former editor of The Paris Review, Brigid Hughes, who until recently was erased from her job. A female writer, A.N. Devers, wrote a Twitter thread outing the magazine for wiping all traces of Hughes, who after her firing started her own magazine, A Public Space. In The Paris Review’s spring 2018 issue, Devers tweeted, Hughes has been reinstated on the print masthead with her proper title: editor.

Twitter often hosts search parties for history. A recent thread by Candace Jean Anderson ignited a widespread hunt to track down the sole woman in a grainy old photo of dozens of male scientists at an international conference. That woman, thousands of retweets later, was revealed to be Sheila D. Minor, who was able to confirm the guess herself. The seek-and-find is now documented on her Wikipedia page.

Only a few weeks after Hughes’ role at The Paris Review was exhumed, she appeared in a New York Times obituary for another female writer, as if this entire episode sprung from a case study on rescuing erased women. Hughes had brought Bette Howland back into public memory after finding her memoir, W-3, on the $1 cart outside a New York bookshop.

“I was really taken with her voice and was surprised that she was a writer I hadn’t heard of before,” Hughes says. She searched for more of her writing, yet the internet provided few leads. “It was one of those instances where the less you could find of her work, the more you were compelled to look.”

After finding an obituary for a family member that mentioned Howland’s son Jacob, the Brooklyn-based editor tracked him down. In the Oklahoma basement of Jacob Howland sat boxes of unpublished stories and remnants of a forty-year correspondence between Howland and Saul Bellow. In the November 2015 issue of A Public Space, Hughes published Howland’s portfolio alongside work of other overlooked artists from around the world, alive and deceased. “This issue built itself around a weft of discovery,” Hughes wrote in her opening letter, “of artists who have been lost to a kind of erasure, intended or inflicted; and works that do not stack on obvious shelves.”

The issue contains a 1968 postcard from Bellow, sent from Canterbury Cathedral to Chicago: “There are always some who have to be dug out.” Nearly two decades later, a 1984 letter from Howland, printed in the December 2017 issue, speaks of “chances” in work and life. On writing, “You get second chances, it’s never too late. (Stop the presses! I thought of a better word! Almost the right one!) This is incredibly lucky.” Life is a different matter. “In life we get quite a few chances, too; but can’t always correct the galleys.”

In the 1970s, Alice Walker discovered the work of the late Zora Neale Hurston. The young writer’s search eventually led her to Hurston’s unmarked grave and a trove of writing. Though Hurston was prolific—she became the most widely published black woman author in 1930s Harlem—her work had been forgotten. What eventually became Looking for Zora was published in 1979, six years before Walker published The Color Purple. Walker’s pursuit brought Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, originally published in 1937, back into view after being out of print for years.

In 1970 female journalists at Newsweek filed a lawsuit against their bosses for sex discrimination. Amazon released a TV adaptation of the Newsweek story a couple years ago, but it was canceled after one season by a male executive who’s since been fired because of sexual harassment accusations. “Horribly meta,” one Washington Post headline read.

“Must history have losers?” wrote n+1’s Dayna Tortorici on today’s watershed moment where men only now are being removed from power for systemic abuse. “The record suggests yes. Redistribution is a tricky business.” More power for one person means less for another, and gender is only one denominator. Less power for one group means less space in the New York Times, poor reviews, or vanishing bodies entirely.

Since 2014, journalist and critic Karina Longworth, based in Los Angeles, has been making a podcast about forgotten histories of Hollywood’s first century called You Must Remember This.

Longworth’s recent series, “Dead Blondes,” resurfaces famous starlets who were often sexually exploited before fading into obscurity (Dorothy Stratten, Jayne Mansfield) or reframes widely beloved sex symbols (Marilyn Monroe, Grace Kelly) in a less reductive portrait of their lives and work. “Their lives were so much richer and so much more detailed than we ever think about,” Longworth says.

“There’s this very visceral sense of ‘It could be you,’” says Julia Carpenter, who started a newsletter on women in history called “A Woman to Know” in 2015. “It could be you who is totally forgotten.” In it she shared historical images, brief biographies, and reading material about the person of the day. Issues covered Virginia Hall, the first female special ops agent in World War II; Zenobia, a warrior queen; and Octavia St. Laurent, a Manhattan drag queen who died of cancer in 2009.

Though the newsletter is no longer active, Carpenter says she “can’t slow down” the rate at which she tweets and writes. “It’s this worry, this pressing fear that it was not that long ago that you didn’t matter.”

In “Overlooked,” the Times does not take responsibility for writing women out of history or acknowledge the deeply ingrained culture that enabled it, as Ann Friedman and Aminatou Sow noted in their podcast Call Your Girlfriend. But some journalists’ self-examination and redistribution of power is slowly changing norms.

At the Times, obits editor Padnani is working to better track women’s deaths. She relies on traditional sources such as regional and international newspapers along with Wikipedia, Legacy.com, and foreign reporters “with eyes and ears in far-flung parts of the world.” Her ask is simple: “Let us know if someone on your beat dies.”

“It’s just that we don’t hear about as many women dying,” Padnani says, citing a higher number of submissions for male subjects. “And that’s why we’re trying to seek out other ways to learn about them.”

In my first reporting job in the Midwest, I loved writing obituaries, combing through Sunday newspapers to find a subject for a longer tribute. I enjoyed writing profiles of living women too, including a 2016 piece on Koryne Horbal, former UN ambassador for women, cofounder of the Minnesota DFL feminist caucus, and recipient of the fourth-highest number of votes in the 1980 presidential election. Maybe you’ve heard of her? I hadn’t.

I learned about Koryne while eavesdropping at a Guthrie Theater play. A woman seated behind me was talking about a recent interview with feminist activist Gloria Steinem in Lenny Letter, a newsletter for women that discusses anything from reproductive rights to Sheryl Crow. “I read that interview!” I chimed in, an eager recent graduate. She sized me up. “Oh really? I wouldn’t expect someone your age to even know Gloria. I drive her to a friend’s home when she visits Minnesota.”

You drive her to a friend’s home when she visits Minnesota? I needed more information.

Turns out Steinem had been there to visit Koryne, whom I eventually tracked down, interviewed, and profiled a year before she died. I can’t forget this email from a male editor, who meant completely well: “Natalie, excellent profile of Koryne Horbal! I thought everyone had completely forgotten about her.”