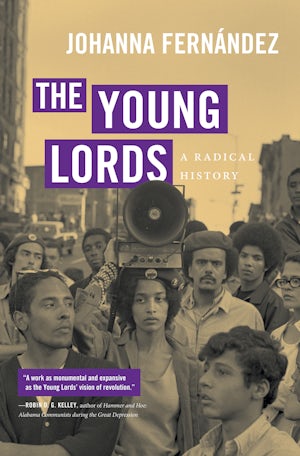

Puerto Ricans demonstrate for civil rights at City Hall in Manhattan, 1967. Photograph by Al Ravenna. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Identified as a distinct condition in the first decade of the twentieth century, childhood lead poisoning, more serious and potentially fatal than its counterpart among adults, is usually acquired through contact with objects that contain lead. Lead is a neurotoxin whose damage to the brain is irreversible. The more acute cases of lead poisoning can cause mild or severe mental incapacity, persistent vomiting, epilepsy, kidney disorders, and in its most extreme case a swelling of the brain that usually leads to death. In the 1960s scientists already believed that between 10 and 25 percent of children living in the slums of Eastern and idwestern cities had absorbed dangerous quantities of lead.

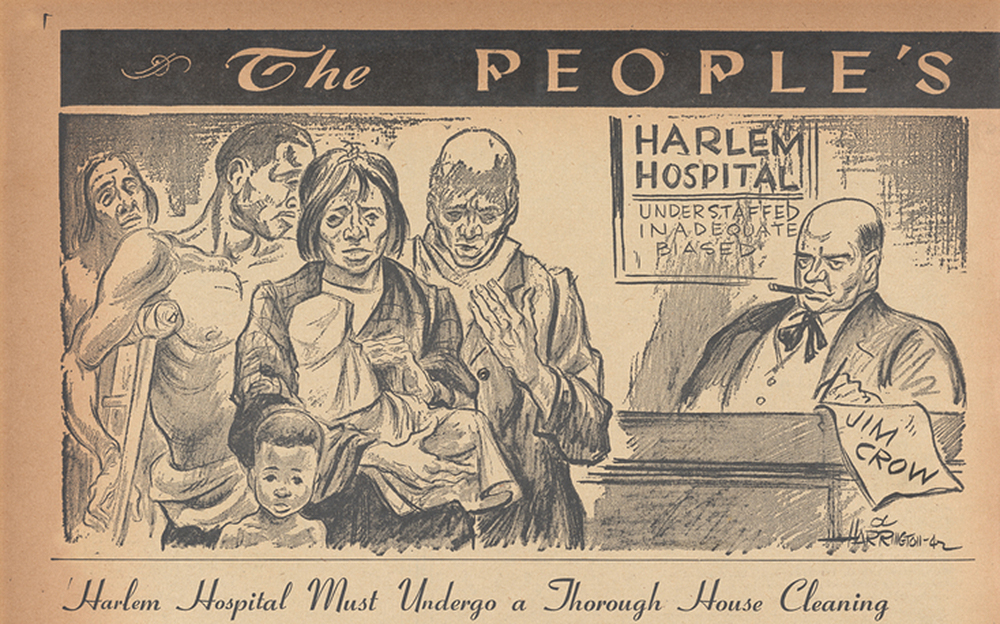

Although lead-based paint was discontinued in the 1940s, the failure of municipal governments to enforce housing codes—requiring landlords to remove old coats of lead-based paint from apartment walls—contributed to the crisis. In 1960s New York 43,000 “old law” housing tenements, deemed “unfit for human habitation” in 1901, continued to house predominantly black American, Puerto Rican, and Chinese tenants. The threat of lead contamination among children in these tenements was ubiquitous. In fact, public health advocates and government officials were aware of what came to be known as the “lead belt.” According to a memorandum prepared for Mayor John V. Lindsay by his special assistant Wenner H. Kramansky, activists were not exaggerating when they denounced the housing crisis in East Harlem and the Bronx as deadly. The memorandum explained that New York’s “lead belt begins in Jamaica East, skips Jamaica West, runs through Brownsville, Bushwick, Bedford Stuyvesant, Red Hook, Gowanus, Fort Greene, Williamsburg-Greenpoint and becomes thicker and heavier in Lower East Side, skips Yorkville and is anchored in Riverside, East Harlem, Central Harlem, Mott Haven, Morrisania, and Tremont.”

In November 1968 New York City’s health department announced that six hundred cases of childhood lead poisoning had been recorded in a period of ten months, three of which had resulted in fatalities. By September 1969 several other children had died of the same cause. And while only six hundred cases were recorded in New York in each of the years between 1966 and 1969, public health reports estimated that between 25,000 and 35,000 children were actually afflicted with the disease each year.

One of the most consequential campaigns run by the Young Lords Organization (YLO), a radical social activist group led predominantly by poor and working-class Puerto Rican youth, involved tackling the long-standing crisis of childhood lead poisoning. Their focus on this issue was propelled by a nearly fatal case of lead poisoning treated at Metropolitan Hospital in East Harlem in September 1969. After falling into a coma due to advanced levels of lead in his bloodstream, two-year-old Gregory Franklin emerged from the hospital with permanent and severe brain damage. His case illustrated the social and economic dimensions of the epidemic. According to media interviews with the Franklin family, before Gregory’s hospitalization, his parents had waged a fruitless eighteen-month battle with their landlord to repair the flaking and falling paint of their apartment walls. After Gregory’s sister also tested positive for lead, it was suspected that a great number of children in their tenement were in danger, especially since the Harlem building had close to one hundred outstanding violations. The young boy’s tragedy was the latest in a string of cases of plumbism, or lead poisoning, among children in the city.

Before the Young Lords launched their Lead Offensive, other groups attempted to bring attention to the issue. In the late 1960s, concerned activists, community groups, and politicians initiated a series of local efforts to pressure New York’s government offices to implement preventive programs that had already been adopted in Chicago and Baltimore. The Citizens Committee to End Lead Poisoning, for example, was founded in August 1968. It was launched at a community meeting in Brooklyn following the death of a child at King’s Hospital. The committee’s housing organizer and leading member, Paul Du Brul, led efforts to lobby local government and to educate communities most at risk.

In the aftermath of Gregory Franklin’s death, city councilman Carter Burden, along with Du Brul and others, held a press conference at the Franklin family’s home at which he proposed “an apartment-by-apartment testing program to be conducted by the Neighborhood Youth Corps.” In response to an incident of lead poisoning in the Bronx earlier that year, Representative Edward Koch also wrote a series of letters to Mayor Lindsay informing him that even Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago—notorious for his unscrupulous political practices—had a more advanced lead poisoning prevention program than existed in New York.

With the November 1969 election fast approaching, the Young Lords got to work. They approached the new Lead Offensive both strategically and practically. They knew that Bio-Rad Laboratories was donating prepackaged lead-screening kits to the city. For the Young Lords, “half the battle lay in obtaining [these] chemical kits” to test the children of East Harlem. In a series of letters and phone calls to the Department of Health, the Lords requested the kits. The department equivocated, but its administrators made promises about the possibility of their future use.

The YLO held a series of meetings in September and October 1969 in East Harlem and at Metropolitan Hospital on the crisis of lead poisoning. They framed the problem in terms of racial, environmental, and housing justice. For several weeks they distributed leaflets and informed residents of their impending door-to-door testing campaign in collaboration with Metropolitan’s residents in training from New York Medical College. One of their flyers read, “We are operating our own lead poisoning detection program with students from New York Medical College, beginning Tuesday November 25, on 112th Street. The Young Lords and medical personnel will knock on your door Tuesday and ask to test your children for lead poison. Do not turn them away. Help save your children.”

The Young Lords, of course, did not have the kits. But they had a dramatic plan to achieve their end. With the expectation that creative disruption would garner media attention and with moral authority in their sails, the Young Lords and their medical allies decided to take their grievance to the Department of Health.

A rumor that the Department of Health had refused to accept the forty thousand kits donated by Bio-Rad Laboratories fueled the Young Lords’ thinking. And community activists viewed the alleged decision of the department as proof of the callousness and opportunism of its officers. In October, at the height of the mayoral election, partly in response to the Gregory Franklin fatality, the department issued a press release announcing a crash lead-testing drive but had not established a concrete plan to obtain or use the tests. According to the Young Lords, the kits were either being allowed to languish unused or were never claimed, despite the growing numbers of lead poison victims in the city. Village Voice journalist Jack Newfield corroborated their version of the story; the Department of Health admitted the error to him after the department’s October press release came out.

On November 24, the day before their door-to-door testing was to begin, the Young Lords conducted a sit-in at the office of Dr. David Harris, the deputy commissioner of the Department of Health. Approximately thirty Young Lords participated, alongside a number of nurses, hospital workers, and medical students, including Gene Straus, Metropolitan Hospital’s chief medical resident. The Young Lords pointedly asked the department if it would be as inactive about testing if the racial composition of the children of Harlem and East Harlem was not black American and Puerto Rican. In a more conciliatory tone, Straus proposed that the department had the opportunity to aid people like those gathered at that meeting, who were already investigating the problem at the neighborhood level. The group asked for two hundred lead-testing kits and successfully persuaded the department to release them that same day.

By the next day, the Young Lords and their nonmedical volunteers had been trained and were conducting door-to-door screenings for signs of lead poisoning among children. These home visits represented a form of itinerant, grassroots organizing that brought the Young Lords campaign to a greater number of people than had visited their office or joined them at demonstrations. The painstaking door-to-door testing, which the Young Lords performed alongside health professionals, afforded the group a measure of moral authority and helped establish their reputation as dedicated young radicals.

As the Young Lords and their team sat around in the homes of residents of East Harlem waiting for young children to urinate—a requirement of the lead poisoning test—the organization saw firsthand the health concerns of stay-at-home moms and grandmothers. Their visits underscored the centrality of sterilization, domestic violence, the stresses of childcare on mothers, and depression, among other issues.

In the spring and summer of 1970 the women of the Young Lords would begin to develop a position paper on the oppression of women of color that analyzed the social and political roots of these issues. These home visits and conversations with mothers about their own complex experiences would also help bring into the open the organization’s internal crisis of male chauvinism.

The Young Lords made their way through the neighborhood, tenement by tenement. They used press conferences and press releases to publicize their findings. On one average day in December, the YLO tested nearly sixty children and discovered that 30 percent of them were positive. Because doctors and medical technicians were present at the door-to-door visits in East Harlem, their findings were credible, exposed bureaucratic inaction, and magnified the Health Department’s negligence. Newfield noted in the Village Voice that the Young Lords were “do[ing] the city’s work in the barrio,” an indication that the group’s activism was being noticed. With news reports that one-third of children living in slums were potentially infected with lead, the department was forced to either disprove the Young Lords’ findings or propose a program for treatment and prevention.

On December 21 a New York Times headline read, city held callous on lead poisoning, and on December 26, criticism rising over lead poison. The president of the American Public Health Association, Dr. Paul B. Cornely, in New York from Washington, DC, publicly criticized the New York City Department of Health for refusing the tests and charged that the race of the predominantly black and Puerto Rican victims played a role in the way the city handled its lead poisoning crisis. Under pressure, the Department of Health later issued a statement explaining that the plans to use the forty thousand tests had been suspended because the Bio-Rad test did not accurately detect the amount of lead in the bloodstream and because it was difficult to collect urine samples from children between the ages of one and three, who have the highest incidence of lead poisoning.

The YLO Lead Offensive, however, succeeded in forcing institutional change. In an interview many years later, one of Mayor Lindsay’s close advisers, Barry Gottehrer, recalled that “the Young Lords were one of a kind. They were serious; they could not be persuaded to stop their muckraking for anti-poverty money.”

In January 1970 the Department of Health established a more exacting lead clause in the city’s housing code and launched the Emergency Repair Program, a subsidiary of the Housing Development Administration, to remove lead paint from tenement walls. The new rule provided that if landlords failed to respond within five days to court orders to remove reported lead hazards from their buildings, the emergency team would make the repairs and bill the landlord for the job. Moreover, the Health Department created an office, the Bureau of Lead Poisoning Control, whose sole responsibility was to launch programs in the city to combat lead poisoning. During the first half of 1970, the city tested more than five times the number of children it had tested in all of 1969. There was also an attempt to promote more aggressively the model of community-based healthcare that the Young Lords advanced.

In 1974 the American Journal of Public Health credited Young Lords activism for the anti-lead-poisoning reform achieved in New York during the early 1970s. According to the journal, the politicization of lead poisoning was key to the passage of meaningful reform.

From The Young Lords: A Radical History by Johanna Fernández. Copyright © 2020 by Johanna Fernández. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.