Originally published by Yale University Press in 2024 as part of its Why I Write series, What Nails It, a collection of essays, will be published in paperback next month. On Tuesday, August 12, Greil Marcus joins Donovan Hohn at Clio’s Books in Oakland, California, for a conversation titled “Oceanic Feelings with Lapham’s Quarterly.” Tickets are available here.

I write for fun. I write for play. I write for the play of words. I write to discover what I want to say and how to say it—and the nerve to say it.

The key word for me here is not fun, play—but discover. I live for those moments when something appears on the page as if of its own volition—as if I had nothing to do with what is now looking me in the face.

In 1965, Bob Dylan described his song “Like a Rolling Stone” as “twenty pages of vomit,” boiled down to a point of hatred—well, he said later, maybe ten pages—but much later, almost fifty years later, he described it very differently. “It’s like a ghost is writing a song like that,” he said, talking to Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times. “It gives you the song and then it goes away, it goes away. You don’t know what it means. Except the ghost picked me to write the song.”

That’s an evocative, romantic account of what anyone who engages in any sort of creative activity experiences at any time. For a lot of people, that sense of an evanescent gift, the genie granting you a wish even if you never asked for it—that sense of visitation—is what it’s all for: a moment of inexplicable clarity. “When you put the music with words and things together, the songs just make themselves,” the 1950s New Orleans rock and roll pianist and singer Huey “Piano” Smith once said. He wrote Frankie Ford’s “Sea Cruise,” he wrote “Don’t You Just Know It,” but he’s best remembered for “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie-Woogie Flu.” (A follow-up, “Tu-Ber-Cu-Lucas and the Sinus Blues,” was not so hot.) But Smith went on: “After you listen on it,” he said of putting things together, “it says something of its own self that you hadn’t planned.” Talking about stand-up comedy, Richard Belzer said the same thing. “The greatest thing for me,” he said, “is when I make the audience laugh in a moment that could only happen that night with that audience.” When Dylan recorded “Like a Rolling Stone,” live in the studio with a six-piece band, over two days and twenty-four takes—twenty-four stabs, false starts, breakdowns—only twice did they make it all the way through the four-verse, six-minute song, and the second time was all trip, stumble, and fall. That’s what Richard Belzer was talking about, that single moment when what you’re writing, painting, singing, telling, speaks in its own voice, which is and isn’t yours: “Sometimes I laugh with the audience because I’m hearing the joke the same time they are.”

That feeling of No, I didn’t think that, I didn’t write that, where did that come from?—and I mean that literally, absolutely having no memory of creating, composing, fashioning, what is there staring at you, saying, All right, here it is, what are you going to make of this?—I remember the first time it happened.

It was 1973. I had dropped out of graduate school at Berkeley after finishing my course work and barely passing my orals—I sat for three hours outside the room where I’d met with three professors, going through every stage of grief, denial, disbelief, fury, and finally not caring. Then I was offered the chance to teach the American Studies Honors Seminar—a two-semester, year-long course for sophomores, with one teacher each from History, English, and my department, Political Science. I was preening over the prestige: no graduate student had ever taught it. I had taken the seminar over 1964 and 1965, with Michael Rogin from Political Science and Larzer Ziff from English. It was a revelation; it introduced me to the terrain, and the conversation, that for good or ill would lie behind what I would end up doing for the rest of my life. It was that classroom engagement, when an atmosphere is conjured up where anything can be said and anything can be understood, where any idea or any argument opens up instantly and naturally into another, until finally the whole class finds itself at the top of a pyramid, dizzy with the notion that now, with the day’s class over, you have to find a way down, which is a version of that out-of-nowhere sentence showing up on a page and asking you if you can take the next step, or fail it, fail the dare it’s throwing at you, abandon it as if it was never there at all.

That’s a translation of how the class actually worked. In the evening a number of us would gather in the seminar room, which was on an upper floor of the great main library, and which was also a library in itself, the books the class was made of—Perry Miller’s biography of Jonathan Edwards, a battered but intact original edition of John Adams’ Discourses on Davila. We’d stay, reading and talking, long after the library was locked up for the night, and at one or two in the morning climb out of a window on a rope, one by one. It fell to the last person out to show up the next morning when the library opened and pull up the rope.

Through most of graduate school I’d been writing for Rolling Stone, then Creem. Starting in 1968, I’d been sending record reviews to Rolling Stone; they were printing them. It was a professional operation, at least compared to the so-called underground newspapers of the time. I was shocked after the first review ran to find a check for $12.50 in the mail a week later. A few months after that I met someone who worked for the paper—that’s what it was called then, a fold-over newsprint tabloid—and started complaining about the record review section: it was all writing about lyrics, nobody was writing about music, nobody was writing about how anything felt, how anything moved, how anything moved you. A few days later I got a call from the editor, Jann Wenner, whom I’d met when we were both freshmen at Cal, though this was five years later and we hadn’t seen each other since. “This is Jann,” he said, as if we’d been talking that day before and he was just picking up the conversation where it had left off. “If you think the records section is so terrible, why don’t you edit it?” So I did, for six months, until after the murderous Rolling Stones show at Altamont at the tail end of 1969, the most violent day of my life, when I was burned out. I recruited the late Ed Ward to replace me, and I kept writing, until I was fired six months later. I went on to the much scruffier and much more try-anything Creem magazine, from Detroit—Rolling Stone in 1968 and 1969 was very try-anything, because there were no rules, except that we were making our own, and Creem wasn’t making any rules at all.

Then in 1972 I left graduate school. I’d always assumed I’d become a professor. I had such great professors at Berkeley—along with Michael Rogin and Larzer Ziff, John Schaar and Norman Jacobson. They were inspiring figures. They were devoted to students. They looked you in the eye. They let you know that they believed you had something to contribute, in a class, in a paper, even to the field, the discipline, the discourse, the conversation that had been going on for centuries, and you felt called to try to live up to that. But as a teacher myself, I wasn’t. I had no patience, and a teacher without patience is not a teacher. Instead of “Tell us what you mean” when a student said something that seemed wrong, I heard “How could you say that?” coming out of my mouth. When I thought everyone was missing the point I’d pontificate for five minutes and shut everyone up for the rest of the class. When I taught again, after nearly thirty years of never stepping inside a classroom, I was ready to learn that if there was a point that absolutely needed to be made, an idea that simply had to be addressed, even a fact that needed to be stated, if I could keep quiet for five minutes, someone in the class would find their way there. I found out that the ideal class would be one in which I didn’t say a word—once, at Princeton, it actually happened.

But at Berkeley I came home from every class angry and in despair. I had wonderful students, three of whom are close friends to this day. But I was cheating them out of their own education. I’d had enough bad teachers not to want to become one. I realized I couldn’t spend the rest of my life doing something I didn’t like and wasn’t good at. At that point the other thing I knew how to do was write. So now, after four years as a journalist, I was trying to write a book.

It was a book that came straight out of that 1964–65 American Studies seminar, when I was nineteen, Michael Rogin was twenty-seven, and Larzer Ziff was thirty-seven. Out of that, and out of living my life to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, rediscovering Little Richard and Elvis Presley, discovering Robert Johnson. Now, for what would in 1975 be called Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock and Roll Music, I was writing about Sly and the Family Stone, within the frame of the black folklore figure Stagger Lee—the bad man, the man of impulse and appetite, a walking advertisement for freedom and revenge, style and death, living life without limits, someone who’d kill someone else over a hat. A real person, as it turned out, one “Stag” Lee Shelton, who in 1895 in St. Louis shot Billy Lyons in an argument over a Stetson hat in Bill Curtis’ saloon—now it’s an office building. Years later I was taken there; I took twigs from a bush in the landscaping.

Right off, maybe the next night, someone composed the street ballad “Stagolee and Billy.” Within days it was traveling up and down the Mississippi. Within a decade or two, with the real facts behind the song forgotten or never known—never mattering: who cared where a song came from when the story it told was so good everyone wanted to claim it?—people would tell you they remembered Stagger Lee, heard about him, knew someone who knew him, in Chicago, Memphis, New Orleans, even New York. Lloyd Price, from Kenner, Louisiana, now home of the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, remembered growing up and watching local pimps and gangsters with their colored zoot suits and Cadillacs: to young boys like him “they were all Stagger Lees.” Stationed in Korea, he staged a play based on the old ballad. When he took his version of the song to the top of the charts in 1958, “Stagger Lee” was stomping through every town in the country; the whole nation sang the song.

Lee Shelton would have heard it himself, in dozens of versions, over the next decade after Billy Lyons was buried and into the decade after that, in and out of prison, until he died there in 1912. But as a song it was also a legend, a myth that from its start traveled through the next century and beyond, as music, in novels, in movies, by 2008 even a porn film, starring Sasha Gray and directed by one Benny Profane.

But all that history was written later. With no facts at hand, even after months of searching, it was the myth I was writing about. I was trying to imagine who Stagger Lee would be, how he would act, how the world would open up before him or close around him. He was a hero. He played out his string. Then it snapped back around his neck. I started with a declarative sentence.

After that, some uncanny cadence took over the words. As if in a trance, the words were making their own rhythm:

Stagger Lee is a free man, because he takes chances and scoffs at the consequences. Others gather to fawn over him, until he shatters in a grimy celebration of needles, juice, and noise. Finally he is alone in a slow bacchanal, where his buddies, in a parody of friendship, devote themselves to a study of the precise moment of betrayal.

What came down, I think, what appeared, were those words “slow bacchanal.” That was the prize, that was the treasure. I just had to figure out what to do with it, find out what it wanted, what images it was making, what the story was that was hidden in the two words.

So that’s why I write: to reach the state where that can happen, and then to see if I can still find my way in and out of that cave. But of course there’s more to it than that—or anyway another version of the same story.

Writing is not only an odd craft, a keeping company with ghosts giving you songs and visitations giving you words. People may say, to other people or themselves, that they want to become a writer, as if it’s a status or a profession where you get a degree and then you’re a writer. Writers write. They can’t help it. They can’t not. At some point defeated, without readers, or without a subject, without something that calls out to be put into the world, without riding on the belief that nothing exactly the same has been in the world before, they might give up. Then they aren’t writers. People sometimes ask writers if they’re going to retire. You don’t retire from writing any more than you retire from breathing. Perhaps at a certain point you can’t do it anymore. For some people what stops them from writing is whatever it is that stops them from breathing. For ten months in 2022 that was how I lived; for ten months I didn’t write a word that went into the world. I couldn’t believe how easy it was.

Writing is rooted in memory: in some alchemy of responses, particular to everyone, with no one’s translation of life the same. My writing is rooted in a doubled memory. It’s a memory of an actual incident, but inside that memory is a false memory, an attempt to remember something that can’t be found.

I was ten in 1955. My family had just moved into a new house in Menlo Park, now famous as the site of the headquarters of Facebook, then famous for nothing. People might tell you it was named for the town in New Jersey where Thomas Edison invented the phonograph. In our house, in a library room where you could squirrel yourself off from everyone else, there was a big tube radio console, and I’d play with the radio at night, trying to pull in the drifting AM signals from stations across the country, from Salt Lake City, Cincinnati, even dance bands from hotels in New Jersey, as if that made some kind of loop back to where I was. One night, a few lines came out. “When American GIs left Korea,” the radio said, “they also left behind countless fatherless babies. Once, everyone talked about this. Now, nobody cares.”

Those words bothered me at the time, but I put them out of my mind. Or so I thought. For the next twenty years, that radio incident would reappear—crashing into whatever I was thinking like an invisible meteorite. As I got older, I realized this was an echo of something other than what the words on the radio actually described—I knew it was an echo of an absent memory, a phantom memory of my own father, whose name was Greil Gerstley, who was lost in a typhoon in the Pacific when his destroyer went down. Those were all of the facts present at the time, and for so long after: no date, no details, no story. I was born Greil Gerstley, but when those words came out of the radio, I wasn’t Greil Gerstley anymore. And although those words made me an echo chamber for the memory they called up, I had nothing to remember: the memory that was called up was silent and blank.

Still, we all have memories of things we didn’t experience: cultural memories that have taken up residence in our minds, built houses, filled them with furniture and appliances, and commanded that we live in them. I never saw Ty Cobb or Babe Ruth play, but they were as real to me growing up as President Eisenhower: I was raised with tales of their hero sagas, even the story of a great-aunt who supposedly slept with Babe Ruth, even with the fact that, when I was a baseball history-mad ten-year-old, Ty Cobb himself lived in Menlo Park. (Afraid he might spike me, I never knocked on his door; I did send him a postcard for an autograph, which he sent back with a signature so fresh-looking it could have been made in 1911, when, my baseball Hall of Fame book said he hit .420. Many years later, I found that his door was open: friends of mine were at his house all the time, asking for the old-timer stories he was happy to tell. What I wouldn’t give now to have had a little more nerve in 1955!)

These sorts of memories, these cultural memories, come to us from all sources, but especially from movies. There is that blank memory, but what explained it to me, as if it lay behind it, was one particular movie: David Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

The famous opening of this 1986 picture seems to parody the American fantasy of home, peace, quiet, and appliances—that is, the all-but-trademarked American dream. But what’s most interesting about what’s happening on the screen is that it may have no satiric meaning at all.

The title sequence has shown a blue velvet curtain, swaying slightly from some silent breeze, casting back to the black-and-white velvet or satin backgrounds of the opening credits for 1940s B pictures. The theme music is ominous, alluring, at first suggesting Hitchcock’s Vertigo, then a quiet setting where predictability has replaced suspense, then horns cutting off all hints of a happy ending. Bobby Vinton sings “Blue Velvet,” his soupy number one hit from 1963—but with the sound hovering over slats of a white picket fence with red roses at their feet, the song no longer sounds soupy, or for that matter twenty-three years in the past. It sounds clean and timeless, just as the white of the fence and the red of the roses, shot from below, so that you look up at them as if at a flag, are so vivid you can barely see the objects for the colors. For an instant, the viewer is both visually and morally blinded by the intensity of the familiar; defenses are stripped away.

In slow motion, a fireman on a fire engine moving down a well-kept middle-class street waves at you, a warm smile on his moon face. Another picket fence, now with blazing yellow tulips. Children cross a street in an orderly manner as a middle-aged crossing guard holds up her stop sign. There is a house with a white picket fence and a middle-aged man watering the lawn. Inside the house a middle-aged woman sits on a sofa; there’s a Pierrot doll on the lamp behind her. She’s drinking coffee and watching an old-fashioned television, a small screen in a blond wooden box with legs, a set from the 1950s, when a TV was sold as a piece of furniture, in this case an object reflecting values of taste and modesty, and also modest enough that the man in the yard might have made the box himself. A crime picture is on. The hand of a man carrying a gun crosses the screen.

Outside, the man watering the lawn seems to sway with Bobby Vinton. The camera shows the faucet where the garden hose is attached leaking spray. The hose catches on a branch. The sound of water coming from the hose and the faucet rises to a rumble that seems to be coming out of the ground. Every predictable gesture is about to shatter from the pressure the predictable is meant to hide. The man clutches his neck and falls to the ground. A dog rushes up, plants its forefeet on the groin of the prone man, and drinks from the spray. The rumble grows stronger. The camera goes down to the ground, beneath the grass, to reveal a charnel house, the secret world, where armies of hideous beetles, symbols of human depravity, of men and women as creatures of absolute appetite, an appetite that banishes all conscience, appear to rise up and march out of the ground to take over the world like the ants in Them! Then the hero finds an ear in a field, and the detective story that will take up the rest of the movie begins.

But it’s the pastoral that stays in the mind, not the nightmare bugs and things-are-not-as-they-seem. Rather, Lynch’s portrayal of things-as-they-ought-to-be feels too elegant to gainsay. It feels whole, not like a cheat. As an obvious contrivance it carries its own reality, because as a mock-up it fixes the real street. For its moment, it feels like a step out of the theater and into an idea of real life. Watching the movie for a second or third time, you can see that the slightly stiff framing and timing of the fireman, the children, the crossing guard, the too-bright images of fences and flowers, are a matter not of making the familiar strange but of getting at how familiar the familiar actually is.

The shots don’t play like a dream, and they don’t play like the beginning of an exciting new story. They play like memory, and they stay in the mind like a common memory laying itself over whatever personal memories a person watching might bring to the images—because what the sequence seems to be showing is a proof that the notion of personal memory is false. The details of the sequence could perhaps be excavated to match specific details of David Lynch’s own boyhood, but what is striking about these quiet, burningly intense images is that nothing in them is specific to anyone. They are specific—overwhelmingly specific—only as images of the United States.

Anyone’s memory is composed of both personal and common memories, and they are not separable. Memories of incidents that seem to have actually happened, once, in a particular time, to you, are colored, shaped, even determined, which is to say fixed in your memory, by the affinities your personal memories have to common memories: common memories as they are presented in textbooks and television programs, comic strips and movies, slang and clothes, all the rituals of everyday life as they are performed in one country as opposed to the way they are performed somewhere else.

The images that open Blue Velvet are images of things anyone watching a movie made in the U.S.A. can be presumed to have seen before, in actual experience or in TV shows or for that matter other movies, to have remembered as if they waved back at the fireman or picked up the hose—as if whatever it is that makes the image significant was determined by the person remembering it, and no one else. But this is not true—and you can take it farther. If personal memory is false, what happens when you try to construct a memory of something that, in fact, you do not remember, but should—that you desperately want to remember?

I think I always knew that the words about the Korean orphans, left behind and forgotten in the United States, lay behind what I ended up doing with my life: rewriting the past, pursuing an obsession with secret histories, with stories untold—with what, to me, were deep, fraternal connections between people who never met or even heard of each other. Such people—as in my second book, from 1989—as the dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck in Zurich in 1916, the essayist Guy Debord in Paris in 1954, and the punk singer Johnny Rotten in London in 1976. Once, a person interviewing me about that book, the poet Lorenzo Buj, asked me about some lines I’d written there: “Lost children seek their fathers, and fathers seek their lost children, but nobody really looks like anybody else. So all, fixed on the wrong faces, pass each other by.” He asked me if I was one of those sons or fathers. I told him that what he was quoting was one of those things any writer stumbles on, that I found those lines and kept them because they made sense of what I was trying to set out at that point in the book, with no personal motive—and that it was only later, rereading that passage, that I realized it was made up of the most autobiographical or confessional words in the book. I thought I was solving a problem on the page. I have a strong sense of privacy; in this case I didn’t want to reveal myself to myself, but instead I revealed myself to anyone who chose to read what I had written. “We think we know what we’re doing,” the Brains sang in “Money Changes Everything” in 1978. They finished the line: “We don’t pull the strings.”

One can of course remember what one hasn’t experienced. Older people tell children, This is what he was like, this is the song he loved, this is how he laughed, how he walked, the team he rooted for. You absorb that; you meet the person who in fact you will never meet, and so that person, never present, becomes part of your memory.

But in my case, none of that was true.

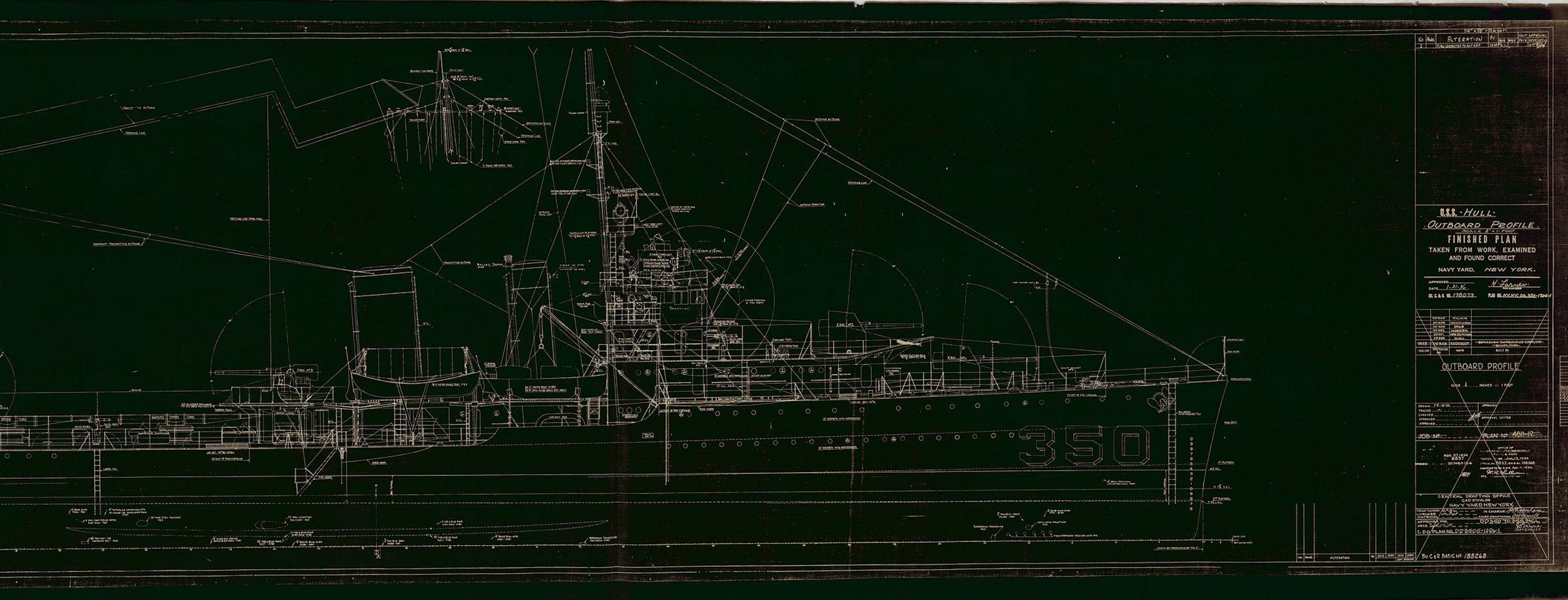

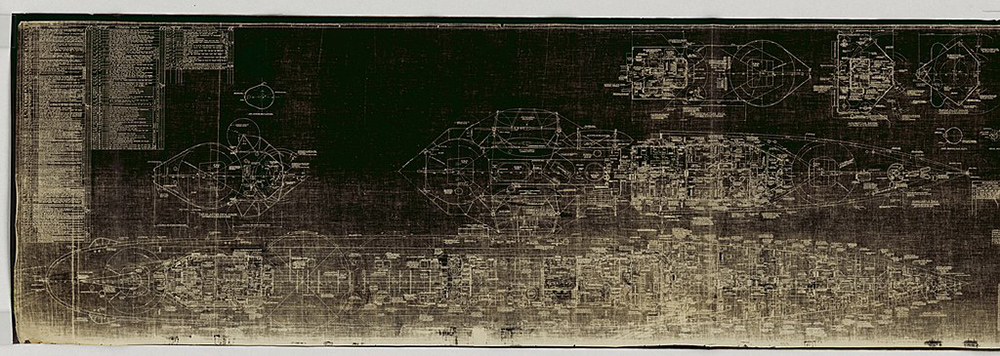

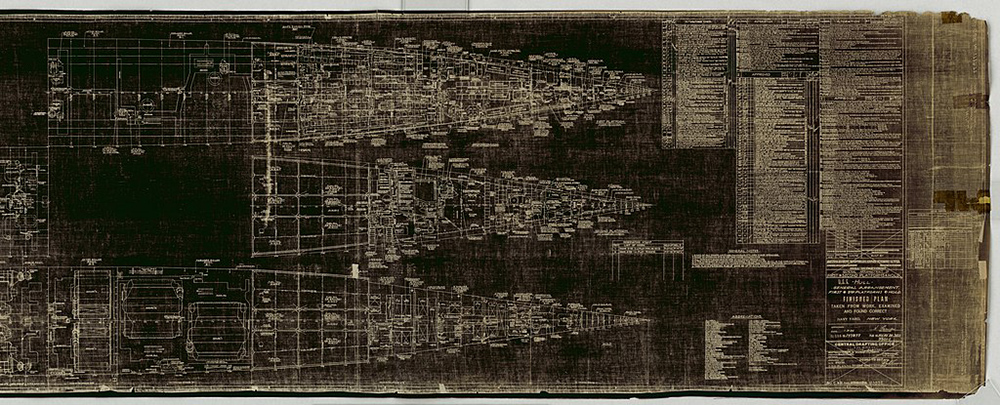

I was born six months and a day after my father was killed in the Second World War: legally, born an orphan. I know that now, but growing up, I never had a date to hold on to, to build from. My mother, born Eleanore Hyman, was from San Francisco; Greil Gerstley, in 1944, at twenty-four, executive officer on the destroyer the Hull, second in command, was from Philadelphia. They hadn’t known each other long when they married in San Francisco on September 7. My mother went with my father to Seattle, where the Hull shipped out.

I was left with the name, which became, for me, a talisman and a mystery. In 1948 my mother remarried to Gerald Marcus, a San Francisco lawyer who grew up in San Jose, and he adopted me, and my name was changed. I don’t remember myself as Greil Gerstley, but Greil was an inescapable name—I always had to explain it, but I really had nothing to tell. The story of the Hull was not told in my family. There were no pictures of my father Greil Gerstley in my house. When I visited my Philadelphia family, there were pictures, but I felt furtive, unfaithful, criminal, when I looked at them. No one ever offered me a picture of my own to keep. There were memories—I was visiting my grandfather and my father’s older brother and sister. There were letters my father wrote to other family members: in one he described how Bing Crosby’s recording of “Blues in the Night” was the only thing that got him through the day. There was even a professionally shot home movie, showing my father in his dress Navy uniform—in the way he looked, in the casual, commanding way he wore his dress Navy cap, so much a match, now, for John F. Kennedy that the footage is hard to look at—but none of that was shared with me. It must have been that to tell the story of who my father was, what he had done, what happened to him and to so many others, would have been too much for a small boy to take on—or that to tell me such things would be, somehow, a breach of faith with my new father, or with my mother, in her new life.

The situation never changed. When I grew older, the habit of not speaking about the past became a kind of prison. I didn’t know how to break out of it. I didn’t ask, and nobody told. My own daughters might ask my mother what it was like to have been married to someone else; I never could. Like many children, I sometimes fantasized that I was not the child of my parents—but in my case, it was at least half true. Or more than half true.

Though I always knew I had a different father than my brothers and my sister, if my father had lived my mother would never have lived the life I came from; none of my siblings would have been born. When, at first, I asked about my father, she would say she didn’t remember. Their time together had been so short, she said. The letters he wrote her from the Hull—he was in charge of censoring mail, which meant he could say what he pleased—were thrown out. He might have told her that, one night, preparing a navigation chart, he named a star after her, but if he did she never told me.

My mother gave her wedding book to her mother—and when, sometime in the mid-1950s, my grandmother took it out and paged through it with me, she told me never to tell my mother she had shown it to me.

So in times of childhood or teenage unhappiness, the fantasy that I might have lived a different life, been a different person with a different name, was more a fact than a fantasy. But it was the kind of fact that, when you try to hold on to it, slips through your fingers like water.

I developed my obsession with the past. I read the history books in the Landmark Books series, from The First Men in the World by Anne Terry White in 1953 to The Witchcraft of Salem Village by Shirley Jackson in 1956 and on from there. They were hardback books; they probably cost about $1.50. I’d read one in a day and then I’d read it again. I used the cultivated mystery of my own past as a spur to reconstructing events as they happened, and as they didn’t—as they might have. This is always the route I’ve traveled, whether writing about Elvis Presley or Bill Clinton, Bob Dylan or Huey Long, about the life Robert Johnson might have lived if he hadn’t been murdered in Mississippi in 1938, the life the Houston blues singer Geeshie Wiley could have lived if she hadn’t disappeared not long after she made records in 1930, about John Wayne in Rio Bravo or Frank Sinatra in The Manchurian Candidate. Events as they happened, and as they didn’t; when in 1964, at nineteen, during the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, when it seemed free everyone was reading Camus’ The Rebel, somebody handed me a copy, the 1956 Vintage paperback edition, and I was instantly transfixed.

I was staring at the cover. I tried to stare into it, My own unintelligible sense of history, never put into words, never fixed in an image, was staring back at me. A black-and-white drawing by the children’s book illustrator Leo Lionni—black and gray, really—showed a crumpled newspaper blowing in the wind. There were unreadable headlines and stories in different languages and alphabets smeared on the single front page.

“If, finally, the conquerors succeed in molding the world according to their laws, it will not prove that quantity is king, but that this world is hell,” Camus wrote in that book: “In this hell, the place of art will coincide with that of vanquished rebellions, a blind and empty hope in the pit of despair. Ernst Dwinger in his Siberian Diary mentions a German lieutenant—for years a prisoner in a camp where cold and hunger were almost unbearable—who constructed himself a silent piano with wooden keys. In the most abject misery, perpetually surrounded by a ragged mob, he composed a strange music that was audible to him alone. And for those of us who have been thrown into hell, mysterious melodies and the torturing images of a vanished beauty will always bring us, in the midst of crime and folly, the echo of that harmonious insurrection which bears witness, throughout the centuries, to the greatness of humanity.” Except for that story, the picture on the cover stayed with me with more force and poetry than any sentences or ideas from the book itself. That drawing was history to me, it was language, it was real life as it happens. A paper flying down the street with headlines of rebellions and refusals and battles and defeats, blowing out of reach. You can see someone chasing the sheet down the street, as if it were the last bit of written evidence of the story of its times, full of sound and fury, gone with the wind, all the assassinations, massacres, failed social experiments, poetic negations, all the raised and dashed hopes of the century that left only these illegible traces in the world, which is, somehow, not nothing. “Shahid watched his lover across the bookshop, a spacious place on two floors with the stock displayed on huge tables; in the past bookstores had always been so dingy,” Hanif Kureishi wrote in his novel The Black Album. “Seeing the piles of new volumes Shahid wanted to snatch them up, not knowing how he’d survived without them. Deedee bought Lipstick Traces, and he followed her to the till, awaiting the bookmark and bag.”

I never expected my untold story to actually appear, as real life—to challenge, as real life, the fantasy that has always been the foundation for whatever it is I write.

But the story did appear. About thirty years ago, my father called to say there was a documentary on the Hull on the Weather Channel. My wife was out; I watched it alone. When she came back, I said, “I just saw my father die.” He wasn’t in the film; survivors from the Hull spoke over stock footage and still photos of the typhoon that killed more than four hundred men from their ship and four hundred from the two other ships that went down in the same storm. You saw their Navy photos, as they were in 1944; you saw them now, laughing, stoic, crying, speaking of the men who made it into the open sea with life jackets, and who, when they were found, had nothing of themselves left below the waist—countless men eaten by sharks. It was the greatest disaster in the history of the U.S. Navy.

A few years after that, a writer named Bruce Henderson got in touch with me. He was looking for information about Greil Gerstley for a book on the Hull. Was I perhaps named for him by a friend? Was I a distant relative? Was there anything I could tell him?

The story he told, based on interviews he had conducted with survivors and people in the orbit of the ship, was terrible. The Hull had been at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but not damaged. Its captain then—the man who trained my father—was respected and trusted. In Seattle, he was replaced by a martinet from Annapolis, a man so vain and incompetent, so impatient with advice from experienced officers, and so sure of his own right way, that when the Hull set out for the South Pacific, twenty men went AWOL, certain that to ship with this man was a death sentence.

With the typhoon looming, Admiral William Halsey—“Bull” Halsey—ordered the fleet to sail into it: “To see what they’re made of.” My grandfather Isaac Gerstley once saw Halsey in a restaurant. He went up to him. “You killed my son,” he said.

With the ship trapped in a trough, with waves on each side a hundred feet high, the captain determined to power the engines to full throttle and smash his way out, while his officers tried to tell him that, in a trough, you cut the engines and wait. The captain panicked. He issued contradictory orders, rescinded them, issued them again. Other officers, who survived to tell the story to Bruce Henderson, begged my father—who was trusted as the captain was not, admired as the captain was reviled—to seize the ship: to place the captain under arrest, take command, and save the ship, in other words to lead a mutiny. There was no mutiny, but Herman Wouk was also in the typhoon, and heard the stories: The Caine Mutiny was based on what happened on the Hull, and what might have happened.

My father refused. In the history of the Navy there had never been a mutiny, he said. He knew, he said, that if he didn’t take command he and everyone else would probably die, and if he did, and they lived, “That son of a bitch will have us all hung.”

The ship was pitching at angles of seventy degrees. My father was thrown against machinery, breaking ribs, bones in his back, and the bones of one hand. A sailor got a splint on his hand. The ship pitched over ninety degrees—and after that the only direction it could go was down. With the ship flooding, my father was pulled from a hatch into the open sea. One survivor says he said to a sailor who approached him, “Don’t try to help me, I won’t make it.” Another remembers him asking for help, and the men near him knowing he had no chance.

As it happens, long after the war, when enough time had passed for those who had been part of it to talk about it, the survivors of the Hull began to hold reunions. In December 2006, in Las Vegas, they held what they determined would be their last, and my older daughter went. She looked like Greil Gerstley, as I don’t; my mother, in a rare unguarded moment, was the first to see it. The people in Las Vegas saw it.

They told her stories, some of them as awful as the one Bruce Henderson told: that when the original captain of the Hull was told, by one of the survivors, that if he had still been the captain, the ship would never have gone down, he shot himself.

Now I know these facts, or I have heard, second and third hand, these stories. I have a story I can tell. I’m telling it now. If it had been told to me when I was a child, I might have, in a true sense, remembered it as if I had been there, with the same instantly recallable immediacy with which I can recite the exploits of Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth. But these facts, severed from the family history that could have given them flesh, and still made spectral by the family life I actually lived, are, really, no more mine than the images that open Blue Velvet.

I can make sense of them, or hold them in my mind, only as scenes from movies—the likes of The Cruel Sea, Victory at Sea, the documentaries The World at War or Why We Fight—or from the Hull movie that, someday, someone might make. But if any such movie were made, the story I have, as a personal story, would be even less mine than it is now—and the truth is that it isn’t mine at all. It is a contrivance—it is a story that I might remember, but don’t. What might have been a personal story dissolves into the public domain of a greater story, of the War, of heroism and stupidity, arrogance and decency, and hundreds of thousands of the dead—and in that sense, whatever personal memory might be found there, the common memory rightly takes away.

What is left one might call neurosis, or fixation, or even a haunting—and it can be used. I’ve used it all my life, more or less consciously, less consciously as I’ve gotten older, as a form of energy, as an impetus, as a way of looking at the world: why I write. For a long time, I thought it was that simple: a nice, organized mise en scène I could use as I chose. But one night in 2023, thinking about all this, trying to fall asleep, instead of trying to remember state capitals or the A to Z streets in Minneapolis, I began to go over words from the titles and part titles of my books, and it all stared back at me like the open mouth of a nightmare killer in a horror movie:

mystery

america

stranded

desert island

secret

history

dead

obsession

dustbin

fascist

invisible

republic

death

love

liberty

disappearance

forgetting

under the red white and blue

patriotism

myth

Those words, many of them, arrived unbidden, just like the phrases that come down out of nowhere, appearing in front of me, daring me to say I wrote them when I know I didn’t. The words invisible and republic made up a book title: the publishers in the U.S. and the UK didn’t like my original title, so I wrote out a list of twenty in ten minutes and told them to choose whatever they liked. They both chose Invisible Republic.

There was no thought involved at all—only that ghost Bob Dylan talked about, a trickster ghost. What I write for. Fun. Play. Discover.

Play that Brains song again.

This article has been excerpted from Greil Marcus’ What Nails It, published by Yale University Press, 2024. Run with permission from Yale University Press, all rights reserved.