Indian group, c. 1860. Photograph by Mathew Brady Studio. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Frederick Hill Meserve Collection.

Like Europeans who ventured into Indian country, Indians who traveled to cities often did so warily. Hostile populations, both Indian and white, might render their journeys perilous, especially in times of war. After the Oneida chief Shickellamy died in 1748, his son John (Tachnechdorus) served as the Iroquois representative in the Susquehanna Valley dealing with Pennsylvania. But the French and Indian War in the mid-1750s shattered earlier patterns of coexistence; now war parties ravaged the frontier and the Pennsylvania government offered bounties on the scalps of Indian men, women, and children. Traveling between the Susquehanna and Philadelphia, John Shickellamy was cursed and insulted by “fearful ignorant people” who told him, “to his face, that they had a good mind to scalp him.” Animosities toward Indians during the American Revolution were so charged that Governor Patrick Henry of Virginia had to order militia companies to protect Cherokee delegates on their way to Williamsburg from “a design of assassinating those chiefs,” and several groups of backcountry settlers planned to murder a Delaware delegation on its way to Philadelphia in 1779. And in the midst of war with the western tribes in 1792, the United States government assigned officers to help get Iroquois delegates safely through the Susquehanna Valley settlements. As if escalating interethnic hostilities did not pose danger enough, travelers on the roads near Philadelphia also faced the threat of highway robbers.

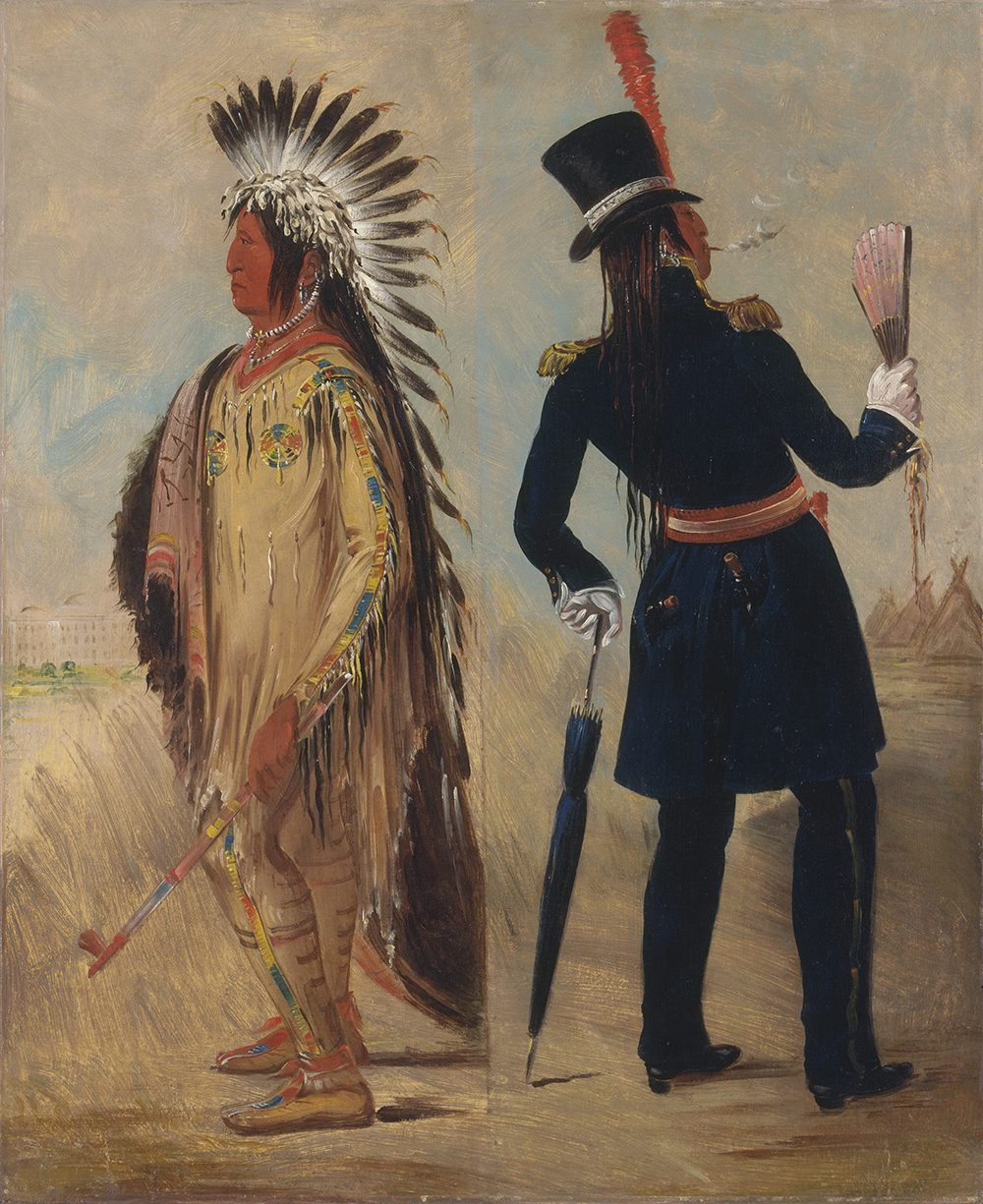

During the early years of the Republic, the federal government regularly assisted Indian delegations by making travel arrangements, providing water transportation and horses, and furnishing certificates, supplies, and escorts for the journey. It also paid daily stipends, covered the costs of their laundry and “entertainment” in the city, and in some cases bought them seats on the stagecoach between Philadelphia and New York. Sometimes military escorts met delegates as they approached town, and Indians entered to salutes of musket or cannon fire and warm words from civic dignitaries. Governor James Hamilton welcomed Cayuga messengers to Philadelphia in early spring 1762 by metaphorically wiping away “the ice and snow which have hurt and bruised your legs and feet in so long a journey.”

It cannot have been easy for Indian people to make their way through throngs of curious onlookers, no matter how warm the welcome. After all, city dwellers read and heard reports of Indian raids on the frontiers, some citizens who had lost loved ones no doubt harbored hatreds, and old fears and cries for vengeance might rise up at any time.

First-time Indian visitors surely experienced a degree of culture shock during their first days in town. Europeans built different kinds of buildings with new styles of architecture around different structures of space and with different concepts of land use. Often laid out in grid form, and characterized by squares instead of circles, cities were visible manifestations of an alien culture and way of life for Indian people. In addition to adjusting to the physical urban landscape, Indians entered a new sensory environment. They heard and smelled the city as well as saw it. The hubbub of crowded streets would have bombarded their senses with a cacophony of noises: iron-rimmed cartwheels rattling on cobblestones, market traders hawking their wares, mechanical clanking from mills, church bells tolling. Although we cannot assume that Native Americans responded to sights, sounds, and smells in the same ways that colonial Americans did (or that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century people responded to them as we would), they surely would have turned up their noses at the noxious smells that emanated from tanneries, tallow chandlers, privies, and sewers, and at the odors generated by large numbers of humans and animals in confined spaces.

The Mohegan preacher Samson Occom, in London in 1766 raising money for the future Dartmouth College, left a famous account of his first Sunday evening in the city, where he “saw such confusion as I never dreamt of—there was some at churches singing and preaching, in the streets some cursing, swearing, and damning one another, others was hollowing, whistling, talking, giggling, and laughing, and coaches and footmen passing and repassing, crossing and cross-crossing, and the poor beggars praying, crying, and begging upon their knees.” Indian people in American cities presumably experienced less assault on their senses than did Occom amid the chaos and cacophony of the imperial capital, but consider John Adams’ entry in his diary in March 1759:

Who can study in Boston streets? I am unable to observe the various objects that I meet with sufficient precision. My eyes are so diverted with chimney sweeps, carriers of wood, merchants, ladies, priests, carts, horses, oxen, coaches, market men and women, soldiers, sailors, and my ears with the rattle gabble of them all that I can’t think long enough in the street upon any one thing to start and pursue a thought. I can’t raise my mind above this mob crowd of men, women, beasts, and carriages to think steadily. My attention is solicited every moment by some new object of sight, or some new sound. A coach, cart, a lady, or a priest may at any time, by breaking a couplet, disconcert a whole page of excellent thoughts.

City talk would also have taken them aback. William Penn said that Indians “speak little, but fervently and with elegancy.” Mi’kmaq people in Nova Scotia ostensibly told the French missionary Chrestien Le Clercq in the 1670s that “Indians never interrupt the one who is speaking, and they condemn, with reason, those dialogues and those indiscreet and irregular conversations where each one of the company wishes to give his ideas without having the patience to listen to those of the others.” For this reason, the missionary added, “they compare us to ducks and geese, which cry out, say they, and which talk all together like the French.” Even John Adams, who was not known for holding his own tongue, noted that New Yorkers “talk very loud, very fast and altogether.” A Scottish visitor in the 1790s said that the Indians he met “never speak in a hasty or rapid manner, but in a soft, musical, and harmonious voice.” In addition to the noise and loud talk, Indian people must have been taken aback by the profanity; as Warren Johnson, brother to the British superintendent of Indian affairs, observed, “There is no oath in the Indian language.”

Yet Indians who came to busy cities may have been less surprised than some other visitors by the babel of languages they heard. Native America was crowded by multiple language families and hundreds of languages long before Europeans arrived and added their languages to the mix. By the time of the Revolution, for instance, Indians in upstate New York were accustomed to hearing not only Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora spoken, but also English, French, High Dutch, and Low Dutch. What language city residents spoke may have troubled Indian visitors less than how they spoke. Indians may have been discomfited by loud and aggressive talk, but they were not always ignorant of its content. The Mohawk chief Hendrick said: “There are some of our people who have large open ears and talk a little broken English and Dutch, so that they sometimes hear what is said by the Christian settlers near them.”

From “The Chiefs Now in This City”: Indians and the Urban Frontier in Early America by Colin G. Calloway. Copyright © 2021 by Colin G. Calloway and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.