All quotations from the Odyssey are taken from Emily Wilson’s 2017 translation.

The Odyssey, if you strip away enough allegory and myth, might serve as a travel guide for the Aegean Sea: which islands to avoid if you hate escape rooms, which cruises to skip if you always forget to pack earplugs, where to get that beef that angers the gods. But how does Odysseus’ trek across the wine-dark sea map onto an actual map of the Mediterranean?

Homer fans have been trying to figure this out—and squabbling over their findings—for as long as the Odyssey has been in the canon. And for just as long other people have been calling efforts to map the Odyssey a complete waste of time. If no one can agree on its physical geography, Odysseus’ imaginary journey is easy to retrace.

In which we take a step back to relate Odysseus’ journey

The Odyssey ostensibly tells the story of Odysseus’ ten-year journey home from war, but much of the poem concerns his absence: his wife Penelope’s clever attempts to stave off aggressive suitors and their son Telemachus’ search for his lost father.

Most of Odysseus’ wanderings are related to us after the fact. When we meet Odysseus, he has been living with the nymph Calypso for seven years on her island, Ogygia. With a little help from the gods, he escapes and travels to Scheria, where the Phaeacians welcome him and invite him to a banquet. There he tells his story.

After fighting in the Trojan War, the conflict at the heart of the Iliad, Odysseus leaves the burning city of Troy to travel back to his home, Ithaca. His fleet of twelve ships is almost immediately blown off course. He and his men end up at Ismarus, where they attack the Cicones, destroy the town, and kidnap the Cicones’ wives. The Cicones kill seventy-six of Odysseus’ men. The remainder get back on course but not for long: at Malea, they are pushed away from Cythera and caught up in storms for ten days. Next they reach the land of the Lotus-eaters, where some of Odysseus’ men succumb to the temptation of eating the addictive flowers; he must force them back to the ship. They travel to the Island of the Cyclopes, where Odysseus fights and blinds Polyphemus, one of Poseidon’s sons. From there they go to Aeolia, a floating island, where King Aeolus gifts Odysseus the bag of winds. After leaving Aeolia they nearly reach Ithaca, only to be blown off course once again when Odysseus’ men open the bag. They row for seven days until they reach Lamos, where the Laestrygonians kill and eat most of Odysseus’ men. Only Odysseus’ ship escapes and travels to Aeaea, where the goddess Circe turns his crew to swine. Odysseus, protected by Hermes, stays a year with Circe, who finally tells him to seek out the prophet Tiresias. Unfortunately, Tiresias is dead, so Odysseus must gain entry to the Underworld, which he finds in the land of the Cimmerians. He speaks to Achilles, Agammemnon, Ajax, and eventually Tiresias, who tells him how to return to Ithaca. Heeding Circe’s warning that they should avoid listening to the Sirens, Odysseus has his men, returned to human form, block their ears with wax and tie him to the mast of the ship, so that he might hear the strange sounds of the Sirens but remain unable to succumb to their magic. From there they navigate a narrow strait between rocky Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis, arriving at the land of Helios. Odysseus tells his men not to eat the cattle they come across, but they do not listen and are punished by Zeus. Only Odysseus survives, floating to Calypso’s island, where he remains trapped for the next seven years. After the gods help him escape Calypso and he tells his story at the banquet, the Phaeacians take Odysseus back to Ithaca. And while the story does not end there, our maps of it do.

In which we debate whether mapping the Odyssey is possible or advisable

In 140 bc, about six hundred years after the Odyssey’s composition, the Greek scholar Polybius wrote in his Histories that he could not agree with Eratosthenes’ quip that “you will find the scene of the wanderings of Odysseus when you find the cobbler who sewed up the bag of the winds.” Neither Polybius nor Eratosthenes knew of a cobbler outside the world of epic poetry capable of sewing a bag that could contain the power of the wind, but for Polybius and for many others who came after him, the Odyssey was a true story with some fantastical elements thrown in for color, not the reverse.

Polybius noted that Homer’s descriptions of fishing near Scylla corresponded directly with Sicilian fishing practices in Polybius’ time. Homer therefore must have imagined Scylla in a real location, and that location must be off the coast of Sicily.

For every Polybius working to read geographic detail in the text of an epic, there is at least one Eratosthenes denouncing the whole endeavor. In the 1980s, in a review of a book on the mapping of Homer’s Odyssey, the classicist Peter V. Jones remarked, “With books on this subject one heaves a sigh of relief to find decent spelling and the pages in the right order.”

In which many individuals try to geolocate Odysseus’ journey

Geographers of the Odyssey often built on the work of their predecessors. In his 7 bc Geographia, Strabo took his cues from Polybius, agreeing that the Odyssey was not a myth and that Homer clearly left clues placing the Odyssey’s setting near Sicily. The famed geographer and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy included longitude and latitude for some of the places in the Odyssey in his own Geographia, an atlas, gazetteer, and treatise on cartography he wrote around 150. He included Lotophagitis (the land of the Lotus-eaters), Circaeum Promontorium (Aeaea, Circe’s realm), Sirenusae Insulae (the island of the Sirens), Scylaeum Promontorium (Scylla) as if they were any other town or geographical feature. Although Ptolemy did not draw any charts of these locations, maps created from his calculations in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries place Lotophagitis in Africa, Circaeum Promontorium near Terracina, Sirenusae Insulae off Campagna, and Scylaeum Promontorium in the Strait of Messina. It is very difficult to transpose Ptolemy’s longitude and latitude figures into our modern conventions. His calculation of longitude begins at a different zero degree than ours, and he used an incorrect circumference of the Earth that distorted his projections and produced longitudinal distances generally one and a half times greater than they should be.

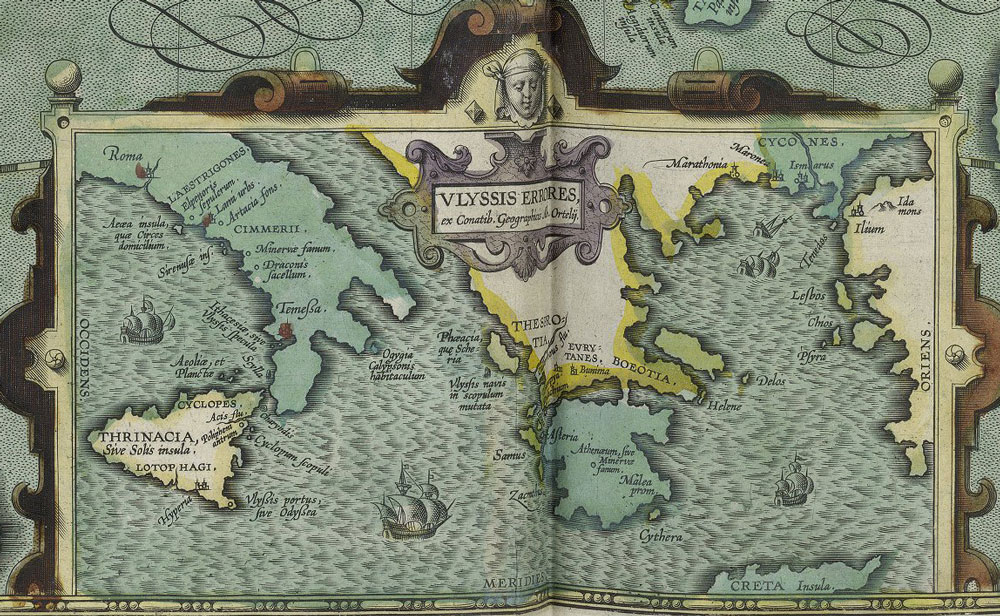

In 1597 the cartographer Abraham Ortelius became the first person to draw a map of Odysseus’ travels. Like many Homeric geographers, Ortelius identifies Scheria, home of the Phaeacians, with Corcyra (now known as Corfu) because of a passage from Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War claiming the Phaeacians were the previous inhabitants of that island. While widely accepted, this identification of Scheria with Corcyra creates a problem. Homer clearly places Calypso’s island west of Scheria, but there is no island in the Ionian Sea west of Corcyra. Ortelius, following in the footsteps of Pliny, mapped a nonexistent island off southern Italy and called it the home of Calypso. The imaginary island appeared on maps through the mid-nineteenth century, and individuals continued to search for it into the twentieth. (Perhaps it had sunk into the sea?)

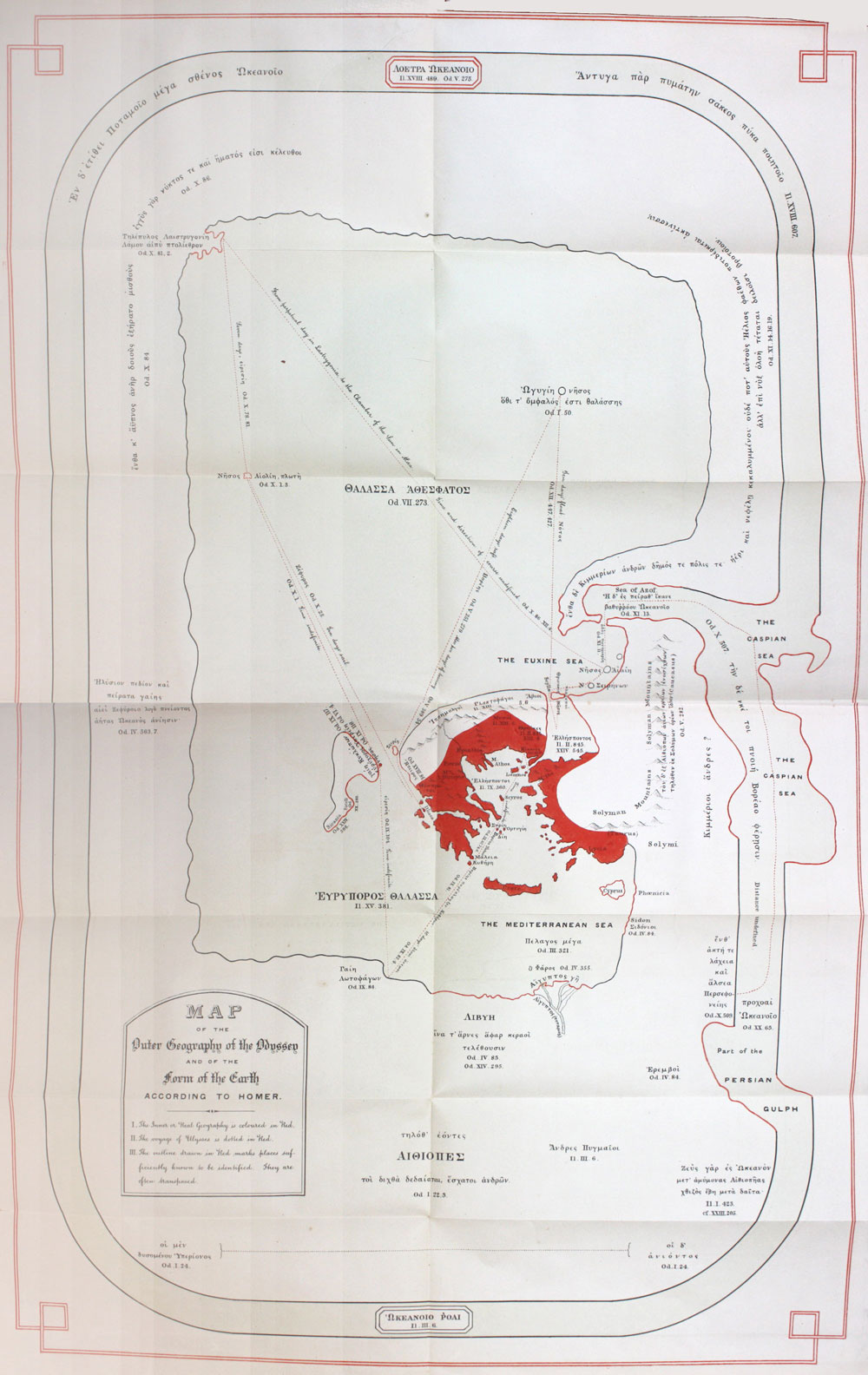

Future British prime minister William E. Gladstone saw Homer’s world as a combination of actual and imagined geography. In volume three of his Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, he included a “Map of the World According to Homer” where a fictional landscape that includes places both real and imagined surrounds the geography of the Aegean Sea. Writing in 1858, Gladstone seems to side with Eratosthenes when he cautions, “Do not let us engage in the vain attempt to construct the geography of the Odyssey upon the basis of the actual distribution of the earth’s surface. Such a process can lead to no satisfactory result.” But Gladstone still found some value in locating Homer’s geographic and topographic references in the real world whenever possible; in doing so, he explained, we understand the extent and nature of Homer’s worldview, the physical reach of his knowledge. While Homer describes territories that are easily recognizable as Greek isles with geographic accuracy, according to Gladstone many other recognizable geographic features—the southern coast of Italy, the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf—are fragmentary, transposed, or (often) both. Gladstone argues that these fragmentary and transposed locations, described without precise features or travel times, were likely known to Homer only indirectly, so he could rearrange them to suit his whims. Gladstone also identified parts of Homer’s world that could never be found on a map of the Earth: the transcendent (the Underworld), as well as the merely mythical (Odysseus’ journey from the land of the Lotus-eaters to Scheria, inclusive).

Later in the nineteenth century, the novelist and translator Samuel Butler relied primarily on topography to map Odysseus’ world, identifying specific locales from descriptions of forests, mountains, and coasts. Based on a close reading of the language and themes of the Odyssey, Butler concluded that “Homer” was a young, headstrong, unmarried woman from Sicily, specifically the region in and around Trapani on its west coast, and that area should be considered Ithaca. His cartographic reconstructions formed a significant part of his evidence for this argument; the descriptions of Ithaca were too specific to point to anything other than Trapani, he insisted, and the author’s familiarity with the region suggested that she lived there. He believed that Scheria was based on Trapani and its environs as well, specifically because of Book Thirteen, “in which passage Neptune turns the Phaeacian ship into a rock at the entrance of the Scherian harbor, I felt sure that an actual feature was being drawn from, and made a note that no place, however much it might lie between two harbors, would do for Scheria, unless at the end of one of them there was a small half sunken rock.” He searched for this sunken rock and other specific features (a nearby mountain, a town jutting out into the sea) and found them at Trapani. Based on those discoveries he insisted that the bulk of Odysseus’ journey took place in and around Sicily. This theory opens up some issues for Butler. If the Cyclopes live on Mt. Erice, the mountain visible from Trapani, and Trapani is Ithaca, then why did Odysseus not recognize how close he was to home when he fought Polyphemus? How did Odysseus travel from Scheria to Ithaca if they are both Trapani? Butler seems to have believed that much of the geographical information in the poem was simply artistic license, which allows him to ignore some details while relying on others as definitive evidence, a useful tactic in case-building that has appealed to argumentative humans throughout history.

Victor Bérard also made use of topography as evidence for his interpretation of Homeric geography. Bérard, a French diplomat and politician, took a voyage around the Mediterranean in 1912, following in Odysseus’ footsteps, taking photographs and gathering information. In 1933 his posthumously published book of photographs from the journey, Dans le sillage d’Ulysse (In the Wake of Odysseus) drew direct parallels between the world of the Odyssey and the world of the twentieth century. His map of Odysseus’ travels, published in his four-volume work Les navigations d’Ulysse (The Navigations of Odysseus) (1927–29), placed Calypso’s cave on an island near Gibraltar, his own particular innovation in the field of Odyssey geography. Gibraltar is certainly west of Corcyra. Bérard’s work spread widely in France and beyond, especially in schoolbooks; it formed the basis of the map published in the popular 1959 textbook Atlas of the Classical World, edited by A.A.M. Van Der Heyden and H.H. Scullard.

In which we ask the question, “But where is Ithaca, anyway?”

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

—C.F. Cavafy, “Ithaka”

The geographical descriptions in the Odyssey are never as detailed or as specific as a cartographer might like. Odysseus himself describes Ithaca’s geography and topography only briefly, saying

My fame extends to heaven, but I live

in Ithaca, where shaking forest hides

Mount Neriton. Close by are other islands:

Dulichium, and wooded Zacynthus

and Same. All the others face the dawn;

my Ithaca is set apart, most distant,

facing the dark. It is a rugged land,

but good at raising children; to my eyes

no country could be sweeter.

So Ithaca is one of a group of four islands, with smaller islands nearby, but it faces west while the others face east. (What does it mean for an island to face a direction?) It has forests and at least one mountain, and it is a good place for raising children. That isn’t much to go on.

But it is enough for some. From antiquity onward many have assumed that Homer’s Ithaca was the island Ithaca (sometimes called Ithaki or Ithaka) in the Ionian Sea. Some disagreed, pointing out discrepancies between Homer’s descriptions and the reality of the island. Others wanted to find proof to support this long-held supposition. In 1868 the famous amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann conducted some minor excavations of what he claimed to be Odysseus’ palace on the isthmus Aetos, on Ithaca. In the few urns he uncovered Schliemann claimed to have found Odysseus’ and Penelope’s ashes, or at the very least those of their children. Schliemann, more famous for his later excavations of Troy at Hisarlik, said that he immediately recognized Ithaca from Homer’s descriptions. He was following growing scholarly consensus about the location of Odysseus’ Ithaca.

In 1920, Frank Brewster insisted that the passages describing Ithaca place the Homeric islands off the west coast of Greece. Brewster therefore identifies these with the Ionian Islands, and places Ithaca on the island of Ithaca, because it is, as Homer describes it, the least suitable of the four islands for chariot racing. Brewster points out that many have disagreed with this conclusion, however, with some contending that another of the islands more closely resembles Homer’s description of Ithaca and others insisting that the Ionian Islands are not Homer’s islands at all. The latter objection developed in part because one of the so-called islands, Leucas, may actually be a peninsula instead. On one side only a shallow marsh or lagoon separates Leucas from the mainland, not the deep water required for naval navigation.

What is an island, anyway? Does it need only be land surrounded by water, or does it have to be water that can be crossed only by boat or by swimming for the land to be truly “surrounded”? How deep was the water around Leucas in the time of Homer? Is it even possible to rely on topography and geographic descriptions to find locations subject to thousands of years of coastal erosion and human tampering? What is it about this story that makes people so eager to locate the exploits of gods, nymphs, and sea monsters in the real world?

In which we examine the potential value of locating sea monsters in your backyard

Unlike Middle Earth or the Hundred Acre Wood, which are arrayed in detailed maps at the beginning of the books that built them, the Homeric world—which wasn’t even constructed out of ink in the first place—does not come with its own pictorial guide. Because no one drew us a fictional landscape and told us it was the site of Odysseus’ voyage, we are left to hope, imagine, assert that his world is also ours. We can demand that Cyclopes and sirens coexist with the geographic specificity of Sicily and Corcyra. Attempts to map the Odyssey seem different from other attempts to locate the sites of famous myths and legends. Atlantis was the site of a wondrous civilization, Troy the landscape for an epic battle; finding them in the real world would mean discovering rich sources of evidence about past cultures. El Dorado’s location seems to have been coveted mainly for the lost city’s purported riches, Bimini for its rumored fountain of youth. But what do we gain by knowing where Helios kept his cows? Or which rocky, uninhabitable cave a kidnapping nymph called home?

In the ancient world, imaginative reconstructions of Homeric and other mythic geographies went beyond mere exercises in intellectual curiosity. Communities wrote themselves into the Homeric world by claiming that their city’s founder had made his way home, like Odysseus, from the Trojan War. Virgil’s Aeneid, in which Aeneas travels from Troy to Italy to sire the people who will one day be the Romans, is the most famous of these. As the scholar Irad Malkin argues in his book The Returns of Odysseus, there was political value in connecting one’s community to such lofty origins.

The desire to feel connected to the story and to bring it into the world we inhabit remains. Homer enthusiasts can even trace Odysseus’ journey on a cruise ship. In 2009, Columbia University’s alumni association held a Journey of Odysseus cruise, which took passengers from Istanbul to Athens, via a loop of the Mediterranean, stopping at several important sites from the poem, including the supposed locations of Calypso’s cave (Valetta); the Phlegraean field where Odysseus battled Polyphemus (Pompeii); Lamos, where the Laestrygonians ate Odysseus’ men (Trapani); and Scylla and Charybdis (Taormina, on the Strait of Messina). Part entertainment, part education, the tour included guided reading of the poem and lectures from experts in the field.

Created for a course on Greek and Roman mythology in 2000, the classicist Peter T. Struck’s online interactive map of Odyssean geography is intended to give his students a general sense of Odysseus’ journey, while recognizing the uncertainty that accompanies any attempt to definitively map Homer’s locations. Struck provided his own interpretation while asking students to read the Odyssey for geographic clues and develop their own. Many of the locations Struck provides are broadly agreed upon (Troy, Ismarus), but he also locates quite a bit of the poem’s action in the western Mediterranean. Struck’s map is one of the few to chart Odysseus’ almost successful return to Ithaca, thwarted by the bag of winds, and he very clearly shows Odysseus traveling in circles.