Wallpaper, c. 1875. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Collection, gift of Harvey Smith.

They began with a wildflower boycott. Elizabeth Britton, cofounder of the New York Botanical Garden and a renowned expert on mosses and ferns, created the Wild Flower Preservation Society in 1901 in hopes of protecting her botanizing sites just outside Manhattan. She modeled the WFPS after the extremely successful Audubon movement, which coalesced when a group of wealthy Boston women pledged to boycott hats decorated with bird feathers. Like feathers, wildflowers were fashionable Victorian accessories, adorning hats as well as dining room tables. An 1887 magazine article described an elaborate centerpiece made of native wildflowers: a pyramid of jack-in-the-pulpits, violets, and red maple twigs with a border of skunk-cabbage leaves. Citing the success of the Audubon societies, early WFPS members argued that if wealthy women refused to purchase wildflowers from pushcart vendors, it would put an end to wildflower harvesting in the countryside, thereby protecting the “victims of the massacre exposed for sale in our city streets.”

Like many women’s clubs, the WFPS aimed to define moral sensibilities during a time when women’s roles in society were highly contested. In addition to boycotting, wildflower advocates argued, women could reform their own behavior in the countryside. “Let us for a moment consider the cruel waste that is going on in the region of Colorado Springs,” WFPS member Mary Perle Anderson wrote. “On certain days in the week special trains run ‘flower trips’ which are largely patronized by tourists. They recklessly pull up and tear up the flowers, and return with great armfuls and basketfuls, and in their ungoverned enthusiasm, they often deck the cars and festoon the engine with them!” This ungoverned enthusiasm, Perle and other WFPS members contended, was leading to local declines in Christmas greens, ferns, laurels, dogwoods, mayflowers, and other delicate and interesting species. “Weddings, by the way,” Elizabeth Britton wrote in the New York Times, “are a new menace to our native plants.”

The WFPS initially aimed to influence the behavior of Anglo-Saxon women, but as the society expanded, it moved toward policing the behavior of so-called new immigrants to the United States—especially children. A 1904 article in Plant World decried the “hordes” that trampled wildflowers in the Hudson Valley, arguing that “fresh air and other charitable societies have unconsciously aided in this destructive work.” Increasingly, the WFPS strove to assimilate immigrant children through education. It was through schools, Jean Broadhurst wrote in Plant World, that women “reach, control, and elevate the masses brought into our country daily.” Local chapters developed and distributed educational pamphlets, lantern slides, and children’s books, and presented plays and pageants, shaping a generation’s relationship to nature.

The WFPS expanded rapidly during World War I, establishing chapters in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and Washington, DC. During the 1920s, the WFPS increasingly focused on a new threat to wildflowers: automobilists. Between 1908 and 1925, the cost of a Ford Model T plummeted from $850 to less than $300. With it, the number of Americans who owned cars increased from fewer than five hundred thousand to more than eight million. Road expansion became one of the main concerns of wilderness preservationists, who argued that the government should preserve large expanses of roadless lands. While wilderness preservationists worried that automobiles would destroy opportunities for peaceful recreation, WFPS members worried that they would destroy native plant species. Automobiles made the countryside outside of the city—and the private country estates of urban naturalists—available to many. Native plants, Elizabeth Britton maintained, had “found a powerful new enemy in the automobile.” John Harshberger, a University of Pennsylvania ecologist and coiner of the term “ethnobotany,” argued in 1923 that automobiles threatened plants and animals with extinction because they could “reach the previously almost inaccessible parts of the world.”

Soon Wild Flower Preservation Society members were split over whether to focus their efforts on immigrants or on automobilists. The schism ended only when Percy Ricker engineered a hostile takeover. Since before World War I, Elizabeth Britton had cultivated a decentralized society in which local chapters handled their own finances, planned their own events, and focused on their local regions. The membership comprised mostly women, with a few male botanists holding leadership roles by invitation. In 1924 U.S. Department of Agriculture botanist Percy Ricker, president of the Washington, DC, chapter, began conspiring to take over the WFPS from Britton, arguing that automobiles had made wildflower preservation a national issue that needed to be addressed by a centralized national organization. Further, Ricker claimed that, under the leadership of women, wildflower preservation had become a “sentimental” subject and that “professional botanists”—meaning male botanists—had become “disgusted with the overzealous efforts of individuals and organizations wishing to forbid all flower picking.”

Unlike some sciences, botany had been considered a suitable study for women as early as the nineteenth century. Of members listed in the first directory of American botanists, approximately 11 percent were women; by 1890 women made up almost half of the Torrey Botanical Society. Along with the professionalization of science at the turn of the century came the anxiety that, as an 1887 article in Science put it, botany was not “a manly study”—that it was “merely one of the ornamental branches, suitable enough for young ladies and effeminate youths, but not adapted for able-bodied and vigorous-brained young men.” Indeed, the view that botany was feminine, and thereby less reasoned, helps explain the efforts of male ecologists to standardize their fieldwork. Historian Robert Kohler maintains that early ecologists imported quantitative and experimental methods from laboratory sciences such as physiology in order to distinguish themselves from “amateur naturalists.” Kohler attributes ecologists’ professional anxieties to the material constraints of working outdoors, arguing that, unlike laboratories, where access was restricted to experts, the field could be accessed by anyone, including tourists. But in distinguishing between laboratory and landscape, Kohler does not consider how the language of “amateurism” was gendered. The field could be accessed by anyone, including women. Often the link was explicit, as in this quote from botanist Willard Clute in 1908:

Too long concerned with leisurely jaunts about the country in search of “specimens” and the pulling of flowers to pieces in order to “analyze” them, botany has come to be viewed by many with a sort of amused contempt which has found expression in the quip that “botany, like croquet, is a fitting pursuit for elderly ladies and ministers.” The boy who elects botany, or the man who teaches it, is regarded by the community as having a feminine streak somewhere in his makeup, no matter what other good qualities he may possess.

By deriding the work of female WFPS leaders as “sentimental,” Ricker sought to redefine wildflower preservation as a masculine endeavor. In doing so, he channeled a broader postwar campaign to characterize women’s professional and suffrage groups as radical and dangerous. Britton recognized Ricker’s challenge to her leadership and attempted to negotiate with him, but in a December 1924 meeting in Cincinnati that Britton could not attend, Ricker led a vote to reorganize the society with himself as president and John Harshberger and Henry Cowles as vice presidents. Britton was given a seat on the new executive committee but resented Ricker. In the margin of a letter from Ricker, in which he described the need of “ladies with such radical ideas” to listen to a “proper presentation of the subject [of wildflower preservation],” Britton scrawled, “A characteristically sarcastic and rude letter. A real sample of his character!”

Unlike Britton, Ricker did not believe that plant species could be protected through appeals to individual behavior; he argued that wildflower decline was due to road building and real estate development, causes over which, in his view, “little or no control is possible.” Unlike animals, which were mobile and whose bodies were regarded as property of the state, plants belonged to the owner of the land on which they grew. Ricker’s WFPS lobbied unsuccessfully for the passage of a federal law by which certain native plants might not be transported in or out of state without a certificate of ownership, referencing the Lacey Act of 1900, which restricted interstate transportation of game and birds. When this failed, the WFPS planned to purchase land and assume ownership of wildflower populations. In the Scientific Monthly, Ricker explained that the WFPS planned to raise funds for establishing “protected sanctuaries,” where native plants would increase in abundance under “expert supervision” (the supervision of male ecologists).

Into the 1930s wildflower advocates increasingly sought to establish permanent sanctuaries that would be owned by private organizations, universities, or governmental agencies and would be managed to promote native plant species. Today one such site—the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum’s Curtis Prairie—is often celebrated as the first major ecological restoration site in the United States; one of its designers, Aldo Leopold, is frequently cited as the sole inventor of ecological restoration, a prophet of modern environmentalist thought. From 1933 until 1948, when he died battling a neighbor’s brush fire, Leopold oversaw cutting-edge work at the arboretum that synthesized ideas from the burgeoning fields of ecology, game management, and naturalistic gardening. The Wisconsin Arboretum’s work on prairie restoration continues to this day; in the 1980s the founders of the Society for Ecological Restoration claimed the arboretum as the first ecological restoration project in the United States.

But the Wisconsin Arboretum was neither the only nor the first effort to restore and study native plant communities—it was just the best publicized. Nor does Leopold deserve sole credit for inventing ecological restoration.

The fact that botany was considered a suitable study for women created opportunities for Eloise Butler. Butler was born on a farm in Appleton, Maine, in 1851, where an aunt who lived with the family taught Eloise and her sister, Cora, about the local plant species. At the age of twenty-three, after teaching high school in Maine and Indiana, Butler decided to move to the rapidly growing city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, a place of sawmills and flour mills. Although she continued working as a teacher, teaching was never her passion. So when, in the summer of 1881, the University of Minnesota offered its first Summer School of Science, Butler jumped at the opportunity. Over the next decade Butler developed a reputation for her algal collecting and observations, and by the 1890s she was a nationally known phycologist. Her sister, Cora Pease, was a well-known naturalist in Malden, Massachusetts, and Pease connected Butler to a community of women scientists that included Elizabeth Britton and Ellen Swallow Richards, the first female instructor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and inventor of home economics and human ecology.

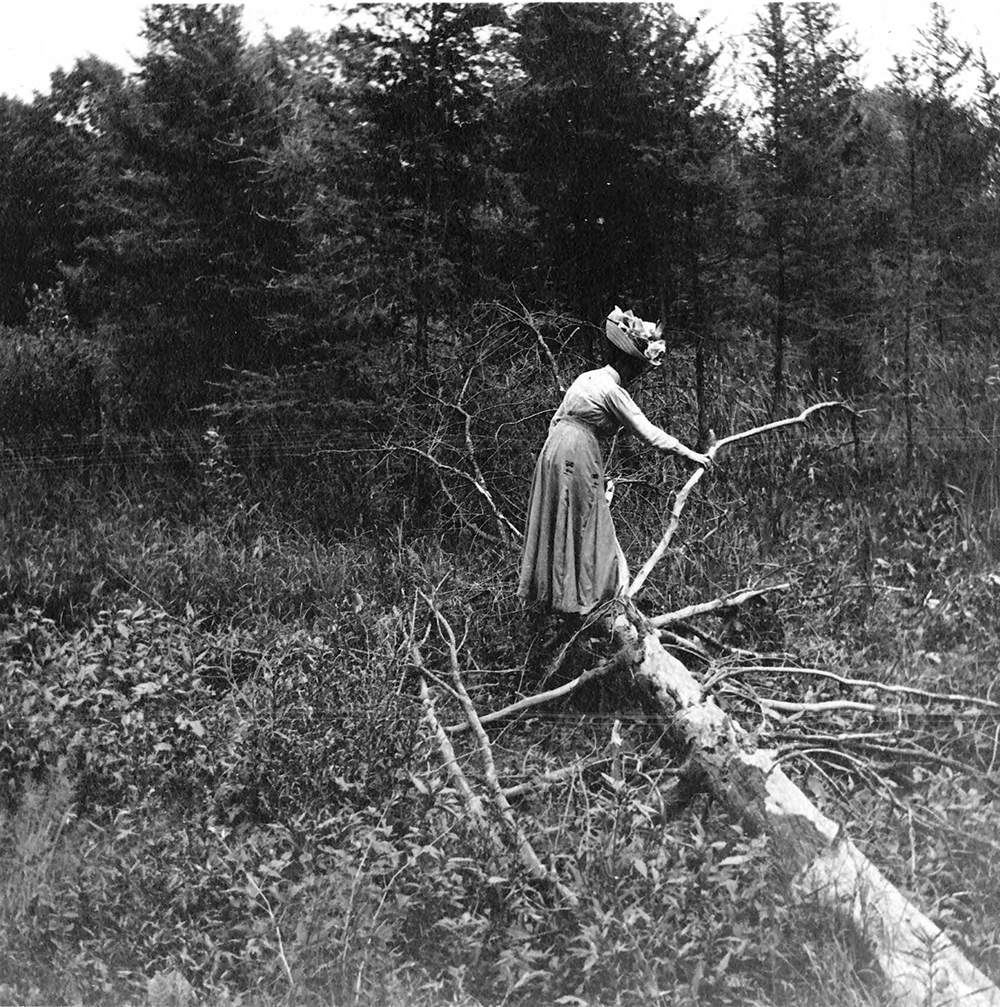

Butler and Pease, self-avowed “bog-trotters,” often traveled together on collecting expeditions. Among her “loves and likings,” Butler included “beauty of line”; “old ruins”; and “the scent of conifers, white violets, twin flower,” and thirteen other plants. Among her “hates,” she listed “the scraping of chairs,” “the odor of carbolic acid,” and “toothpick shoe heels.” In 1907 Butler organized local science teachers to petition the Minneapolis Park Board for space to establish a botanical garden “to show plants as living things and their adaptations to their environment, to display in miniature the rich and varied flora of Minnesota, and to teach the principles of forestry.” Rather than fight to preserve wildflowers in sanctuaries, she would endeavor to reintroduce them.

Butler favored native species. At the turn of the twentieth century, American horticulturalists were divided between Victorian cosmopolitanism and an emergent austere design aesthetic. Acclimatization societies favored cosmopolitanism and sought to import useful or beautiful species from other continents. At their urging, many species today considered “invasive”— Norway maple, European starlings, and brown trout, for example—were introduced to North America in the name of environmental improvement. Against this spirit of biotic cosmopolitanism, a growing number of naturalistic landscape architects began to advocate for an aesthetic unique to the United States and distinct from European garden design. These designers opposed nonnative plants on aesthetic grounds; they dismissed Old World plants as showy and florid and rejected the straight lines of the Renaissance garden. Moreover, naturalistic gardeners argued that native plants were better adapted to local environmental conditions, and therefore required less maintenance.

Butler’s Wild Botanic Garden, the first public wildflower garden in the United States, opened on April 27, 1907, on three acres of tamarack swamp and hillside donated by the Minneapolis Park Board. A local newspaper article titled shy wildflowers to be given hospice announced that the garden would “supplement the textbooks for students.” Rather than travel long distances to show students relict plant communities, botanists would now be able to teach from an organized, easy-to-reach location. The express goal of the Wild Botanic Garden was to “avoid all appearance of artificial treatment.” The word appearance was key here. The garden was a highly managed place, but it was designed to appear wild. Once transplanted, plants would be allowed to grow, in Butler’s words, “according to their own sweet will and not as humans might wish them to grow.” Elsewhere, she wrote, “My wild garden is run on the political principle of laissez-faire.” Seedlings would not be watered once they were well rooted, and they would not be fertilized. But they were not entirely unmanaged—Butler and her colleagues thinned specimens when they were too prolific, and they uprooted nonnative plants like dandelion, burdock, and Canada thistle. For Butler, the aesthetics of wildness and nativity were closely connected. She critiqued “foreign plants” for looking “formal and stiff,” much as “impaled butterflies do in a museum case.” And she critiqued Minneapolis suburbanites for planting lawns of “monotonous, songless tameness.” Butler purported to prefer the “fragility, delicacy, and artless grace of the wildings.”

By the end of her life, Butler had planted 710 species at the Wild Botanic Garden, which joined the more than four hundred species already growing on the site. Butler curated the Wild Botanic Garden from its founding in 1907 until her death in 1933. Wearing brown overalls and high-laced black leather boots, armed with a broken-off machete and wearing a park watchman’s star pinned to her chest, she would run out the “spooners” who might trample her plants. You can still visit the garden today.

Excerpted from Wild by Design: The Rise of Ecological Restoration by Laura J. Martin, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2022 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.