Reading Woman, by Pieter Willem van Megen, c. 1760. Rijksmuseum.

I generally understand every thing I read, all but what’s Latin, and that I skip.

—‘T.G.,’ The Female Tatler, No. 81, January 9–11, 1710

I am very sensible, madam, of the absurdity to speak Latin in a Ladies presence, but I am sure you understand it; and for the sake of those who do not, I will translate them after my way, that is somewhat Paraphrastically.

—Matthew Morgan, Dedication to a Poem to the Queen upon the King’s Victory in Ireland, and His Voyage to Holland, 1691

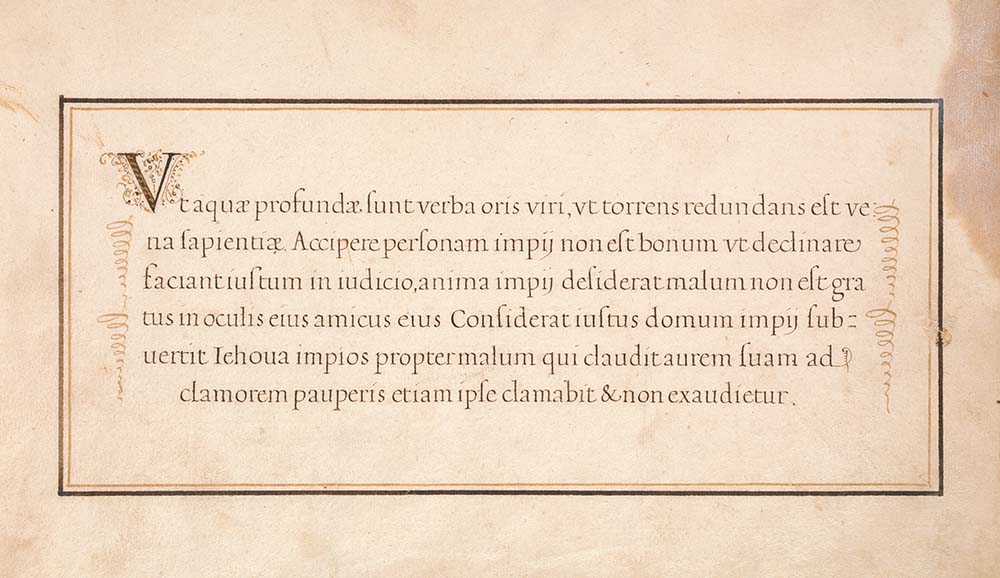

By the middle of the eighteenth century, it was possible to find introductory, digested accounts of more or less any area of intellectual life, including classical languages and literature—forms of knowledge once thought synonymous with being a formally educated gentleman. These introductory works give us some insight into the varied levels of classical literacy enjoyed by readers. In her influential Essay to Revive the Antient Education of Gentlewomen (1673), Bathsua Makin—herself an experienced teacher, former royal tutor, and prodigious polyglot—argued for women’s capacity to learn and offered commonsense advice on the kinds of books that might help young women learn grammar and classical languages. Her summary of the kind of syllabus she was advising—and in fact, that she offered to teach at her newly founded school in Tottenham High Cross—gives some sense of the limits of classical competency in an aspirant student of this kind. She recommends a simple course of learning a thousand sentences in six to nine months, and dismisses the idea that students might try to learn a whole language and its grammar:

To Construe the Grammar, and to get it without-Book, is at least the task of two years more; and then, it may be, it is little understood, until a year or two more is spent in making plain Latin. My Reader, it may be, thinks I have forgot, or purposely omitted to allow time for these things, without which nothing can be done.

Having dispensed with the idea of learning the whole language, she explains the pointlessness of extensive study:

To commit the very Accidence and Grammar to memory, requires three or four years, sometimes more, (as many can witness by woful experience) and when all is done, besides declining Nouns, and forming Verbs, and getting a few words, there is very little advantage to the Child. This being supposed, it’s not likely Children of ordinary Parts should in so short a time be improved in any competent measure in the Latin Tongue.

Children “of ordinary parts” would not much benefit from declensions and verb conjugations, and besides, there was the danger that even after all this, students would still not have much to show for it:

If we should dance that wild Goose chase usually led, it would require longer time; ordinarily Boys learn a Leaf or two of the Pueriles, twenty Pages of Corderius, a part of Esop’s Fables, a piece of Tullie, a little of Ovid, a remnant of Virgil, Terence, &c. and when all this is done, they have not much above half so many words as this little Enchiridion, the Janua [her favored pedagogical model], supplies them with.

Nodding acquaintance with the major works of a few celebrated authors and a thousand sentences will have been the limits of many early eighteenth-century readers’ knowledge, placing a ceiling on their ability to understand all of the complex and playful commentary of many of the imaginative neoclassical works of the period.

The kinds of limited skills evident in Bathsua Makin’s schooling was nonetheless something that many middling parents and aspirant students wanted to acquire. Tuition in the classics was part of the education on offer to students in a range of non-elite contexts: the Post Boy of September 1700 contains an advertisement for a school near Somerset House on the Strand offering education in “the Rudiments of the Latin, French and English Tongues, Writing and Arithmetick” at ten shillings a quarter, or twelve pence a week; while “[a]pprentices, and such as are grown to maturity, may be instructed in Arithmetic, &c. Suitable to their Trades and Employments, between five and eight these Winter Evenings.”

It follows from this that if we encounter the witty, learned, heavily referential neoclassical satires of the early eighteenth century and read them assuming that they were immediately and wholly accessible to all their first readers we are probably wrong. Early eighteenth-century readers cannot necessarily have been secure in their ability to understand the books they read, and they were not necessarily encouraged to feel secure. In the judgmental margins of works of the time, readers commonly mock their contemporaries’ linguistic failures. The Catholic William Blundell was unable to attend university because of his faith, and he professed his own poor Latin. However, this didn’t stop him from repeatedly commenting upon errors and infelicities in the authors that he read and creating sections in his commonplace book in which to list examples of bad Latin. He regularly calls out “pityfull Latin,” and having noted “sondry faults” in Thomas May’s Breviary, a history in Latin of the English civil war and parliament, he went on to comment that “It is very remarkable that the English in this age have no great tallent in writing Latin prose.” Alexander Pope’s copies of pamphlets by contemporary writers are also peppered with snarky comments about his rivals’ lack of learning. His edition of the anonymous Gulliver Decypher’d, a critique of Swift’s prose satire, contains a mean little list of its author’s malapropisms and typos, including the mistranscription of βασιλευς as ΒΑΣΙΛΙΣ. In his copy of Matthew Concanen’s A Supplement to the Profund (1728), Pope again laid into an adversary’s lack of Greek. In his work, Concanen had questioned Pope’s erudition, and in his notes on the Supplement, Pope went to town in exposing his adversary’s limited classical knowledge, writing of Concanen “his remarks and his observations proceed almost all from his own ignorance of ye Greek.” The reality was that Concanen was a barrister, later attorney general of Jamaica, and had in all likelihood more extensive university education than the Catholic Pope (Concanen’s early life is unknown). Calling out another writer for substandard learning served the dual purpose of discrediting the publication and shoring up Pope’s own contested credentials as a translator of the classics.

A sensitivity to a potential lack of classical fluency was particularly evident in relation to female writers and readers. Periodicals of the time poked fun at women who wanted acquaintance with classical culture but lacked the language to master it. The Censor of April 1715 sketched a satirical portrait of a lady who loved to listen to Greek:

She has indeed a great many odd Humours, and innocent Vanities, which it would be ridiculous to offer at correcting in One of her Age; tho’ I am in some hopes of getting off from a Task she has oblig’d me to perform for these Ten Years together, which has been to read to her an Hour once a Week out of some Greek Author. ’Tis true, she does not understand a Tittle of my Lecture, but admires it for a fine sounding Language; and Madam Dacier her self cannot be in more Transports than my Cousin is upon my reading of Homer: When any one rallies her upon this Subject, she only replies, she has as much Reason as the Ladies who are pleas’d with Italian Opera’s.

A letter to the Female Tatler of January 1710 also featured the avid female reader without classical learning: “Ladies, I Am a Young Gentlewoman that take great delight in Plays and Opera’s, and read the Tatlers both Male and Female as constantly as they come out. I generally understand every thing I read, all but what’s Latin, and that I skip.” Even in the formal and flattering contexts of dedicatory prose such constraints were acknowledged. An address to an aristocratic female patron in a panegyric from 1691 reads: “I am very sensible, madam, of the absurdity to speak Latin in a Ladies presence, but I am sure you understand it; and for the sake of those who do not, I will translate them after my way, that is somewhat Paraphrastically.”

Countless examples from women’s correspondence of the period show the gendering of this concern about comprehension:

We separate after dinner till tea calls us together at half an hour after six, and then Homer’s Iliad takes place; Miss Hamilton reads the notes and translates all the Greek words and passages as she goes along, with so much ease that the first day she read (till I looked over her and saw the Greek characters) I thought they had been all translated! The Dean now makes her read the Greek first, and so we have the pleasure of hearing that fine-sounding language, not without some mortification at not understanding it.

“Yesterday a charming man dined here—a clergyman, his name Bighton, an enthusiast in botany…I sat by in silent admiration, like the lady who ‘loved to hear Greek though she did not understand it.’”

Voltaire writes to a correspondent: “If you load this allegory with another allusion to the first book of Virgil, it will not be understood by the women, and by the young trippers [coxcombs]. Even many men of letters in reading it will be at a stand for a little while till they remember the passage of Virgil…T’is not a single emistiche known by every body that strikes a full light on the mind of the reader.” And there were those who recognized that a lack of classical literacy made other areas of potential knowledge inaccessible to them. Elizabeth Bury, a self-taught nonconformist diarist, reportedly rose at four every morning to pursue studies in Hebrew, medicine, mathematics, French, music, history, divinity, and philology. Yet in an edition of her writings published after her death, her husband wrote that

She would often regret, that so many Learned Men should be so uncharitable to her Sex, as to speak so little in their Mother-Tongue and be so loath to assist their feebler Faculties, when they were any wise disposed to an accurate Search into Things curious or profitable, as well as others; especially (as she often argued) since they would all so readily own, That Souls were not distinguishable by Sexes. And therefore she thought it would have been an Honourable Pity in them to have offered something in Condescention to their Capacities, rather than have propagated a Despair of their Information to future Ages.

There were also many male readers who had, at best, a patchy understanding of the classics. There were the self-taught, and those who had forgotten whatever they had learned in formal settings. As we admire the assured classical joking of the early eighteenth-century literary canon, we should also be mindful of the experiences of those who half got the joke or the classical allusion, and the way many satires played with an anxiety about the right kind of learning. For a variety of reasons, the everyday use of Latin, the great lingua franca of the medieval period, was on the wane. Despite the number of hours and years dedicated to Latin on the school curriculum, it was a complaint of educationalists from the mid-seventeenth century onward that the considerable linguistic apprenticeship in schools guaranteed only a mediocre output in terms of pupils’ abilities in written and spoken Latin, let alone Greek. Even educated English readers were less likely to have fluency than they did a century before, and yet this is the era of the great love affair with classical translation, imitation, parody, and play. Latin and Greek remained at the heart of university education and European culture throughout the period, but the assumption that, for example, even elite and well-educated English writers would continue to write in neo-Latin as a primary form of cultural exchange was unquestionably in decline.

Excerpted from Reading It Wrong: An Alternative History of Early Eighteenth-Century Literature by Abigail Williams. Copyright © 2023 by Abigail Williams. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.