Mountainous Landscape with Approaching Thunderstorm, by anonymous, nineteenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Van Day Truex Fund, 2006.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

“You will not replace us.” If you followed the coverage of the events in Charlottesville, you likely heard that slogan chanted by white nationalists. The fear that white people face an existential threat is common among the groups and digital platforms ranging from Greece’s neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn to the U.S.-based Occidental Observer that constitute white nationalism, which often refer to “white genocide.” That term dates to at least the 1970s, but the history behind it is much older, stretching back to some of the earliest intellectual roots of Nazism via the Völkisch movement of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Germany.

Struggling to establish a national identity during a period of significant social upheaval, Völkisch intellectuals wanted to build a society based on a racially defined German spirit. The turmoil of their era meant this racial spirit was viewed as constantly under threat. Because Völkisch thought and its anxieties were a significant influence on the ideas that shaped the Nazis, postwar Nazi sympathizers kept them alive, ensuring their influence would continue with today’s white nationalists. A better understanding of this history not only gives us insight into the fears that motivate them but also highlights the challenges faced in countering their rhetoric.

The phrase white genocide emerged in the decades following World War II. One early appearance is in a 1972 issue of White Power, the official newspaper of the National Socialist White People’s Party, in a piece proclaiming that the “Over-Population Myth Is Cover for White Genocide.” The article accuses “birth control campaigns” of focusing on white people while ignoring overpopulation in countries without white majorities, threatening a near future where “whites will be outnumbered four to one.”

Nearly two decades later, the term achieved prominence among white nationalists through the writing of David Lane, a member of the Order, a terrorist organization that committed armed robbery and murder, among other crimes, in the 1980s. Imprisoned in 1985, Lane began writing prolifically, producing influential tracts like the “White Genocide Manifesto.” Today his influence is widespread and can be seen in the repetition of the number fourteen among white nationalists, a reference to the manifesto’s concluding fourteen words: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”

Lane’s manifesto expanded on the NSWPP’s use of the term, offering a laundry list of racist anxieties derived from the fear of “a Zionist conspiracy to…exterminate the white race,” including promotion of “the unnatural act of homosexuality,” “miscegenation,” and “abortion” in order to diminish white populations. Fears of white population decline figure heavily throughout the manifesto, as Lane frets over the unsourced “fact” that “approximately two percent of the Earth’s population is white female of child-bearing age.” He also connects this decrease to “the denial of jobs to white men through so-called affirmative action and other nefarious schemes,” as well as a “Judeo-Christianity…dedicated to the concept of racial leveling.”

Lane’s manifesto consolidated anxieties about racial decline under the term white genocide, yet many of these fears are far older than the term itself and have important roots in the racialized ideas of “Germanness” espoused by the Völkisch movement.

The Völkisch movement was a loosely organized set of intellectuals and groups born between the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 and the unification of Germany in 1871, when Germans were scattered across a number of separate states and other Europeans were defining and asserting their national identities. Volk means “folk” or “people” in German, connoting the people as a nation, a unified whole. Völkisch intellectuals sought to establish an identity of their own, a “Germanness” that could be used to stitch together a fractured people.

To do so, they drew heavily on folklore and Romanticism. Folk traditions, rural spaces, and the peasantry were held up as emblematic of the “true German spirit.” A connection to nature was especially important, as historian George Mosse notes in The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich, because it was “credited with engendering in the population such qualities as sincerity, integrity, and simplicity,” which Völkisch thinkers greatly valued. This connection between race and place formed the foundation of what Walther Darré, a Völkisch activist who would later become minister of agriculture in the Nazi regime, called “Blut und Boden,” meaning blood and soil—another phrase chanted by racist demonstrators in Charlottesville.

The Revolutions of 1848, however, marked a growing spirit of liberalism in the German states. While these revolutions were unsuccessful, they demonstrated a desire for increased political rights and free-market reforms—ideas the revolutionaries borrowed from English liberalism and other international sources—that remained popular until well after unification.

At the same time, ongoing industrialization and urbanization threatened to fill the countryside with smoke-spewing factories. Mosse points out that German coal production, a key indicator of industrial development, increased twentyfold between the middle of the nineteenth century and unification in 1871; it had tripled by the start of the twentieth century. This rapid expansion devastated the livelihoods of the peasant farmers who were the subjects of Romantic Völkisch notions, forcing them into the squalor of ever-expanding cities. Unification accelerated these developments, as the newly established state sought to become an economic power in Europe by ratcheting up manufacturing. Industrial modernity had come to Germany, and with its ecological devastation and importation of foreign ideas came threats to the burgeoning ideal German spirit Völkisch intellectuals were trying to establish.

Such changes were anathema to Völkisch thinkers, and denouncing them became a key theme in their writing. Paul de Lagarde, an academic whose 1886 book German Writings was very influential on the tradition, decried German liberals’ penchant for foreign “intellectual goods” as “the utmost curse upon any country.” Included in these imports was what was presumed to be an obsession with material wealth over the idealism of Völkisch unity.

Guido von List, a native of the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire who yearned for a pan-German union of the two countries, also renounced “those outward forms of modern life whose vacuousness and corruption are now beginning to disgust us.” Like Lagarde, List despised “foreign” influences, especially Austria’s Slavic population, who had become newly empowered by a series of reforms in the late nineteenth century. He, along with many of his contemporaries, viewed these reforms as a direct threat to Austro-Germans’ own preeminence in the empire.

The distaste for “outside” cultural influences also extended to Christianity, which was seen as alien to the Völkisch conception of Germanness. Thinkers like Lagarde sought to transcend Christianity by stripping it of its universal view of humanity and “Germanizing” it in line with Völkisch principles. List and others argued for a return to pre-Christian pagan traditions, which List called Wotanism, after the German name for Odin. In his book Secret of the Runes, he claimed to have had visions revealing secret knowledge of ancient Germanic runes, knowledge that could redeem the German spirit from modernity’s upheavals. He also blamed Christianity for displacing the ancient folk religion such visions represented. This “life-denying religious system” thereby ignored the fundamental “natural laws” of racial difference and therefore threatened to “destroy the noble race” of Germans.

These reactions to non-German cultural elements pushed Völkisch thinkers to define Germanness in racial terms. Liberalism and Christianity served a negative role, demonstrating what the ideal German was not. Long-standing European anti-Semitism was key: for many Völkisch intellectuals, Jews were a foreign influence living in the heart of Germandom. They were also closely associated with commerce and the financial systems underpinning industrialization, qualities Völkisch thinkers believed to be opposed to the German spirit. Echoing many of his contemporaries, Lagarde argued that “for modern Jewry, monetary possessions…are not ends in themselves but rather a means toward dominance,” and thus “every Jew who is a nuisance to us represents a serious reproach to the authenticity and truthfulness of our Germanness.”

The Völkisch movement wanted to create a national identity for Germans during a period of great instability. Lacking national unity and beset by modernity, these thinkers were trying to create a Germanness at a time when they thought it was in constant peril. Völkisch intellectuals feared the German spirit would be eclipsed by a focus on the material values of industrial capitalism, which ran counter to the presumed spiritual qualities of the Volk. The speed of industrial expansion only exacerbated these concerns, particularly as its ecological impacts imperiled the natural spaces where, as Völkisch author Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl wrote in Land and People, the German people could be found in their “purest…natural form.” “Foreign” influences like liberalism and Judaism were blamed for this “corruption,” as was an “alien” Christianity.

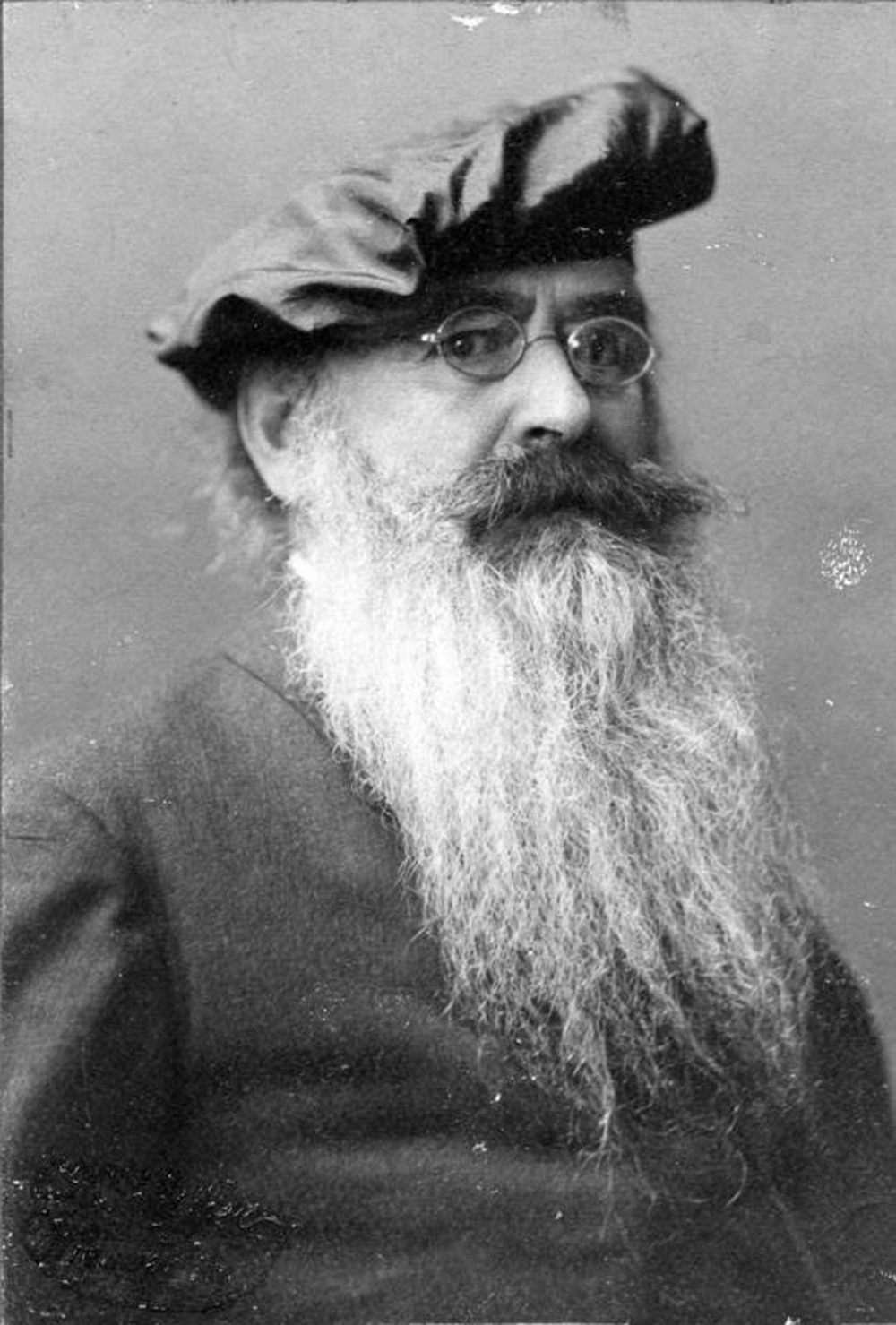

Such views bear a remarkable similarity to those present in Lane’s manifesto. Indeed, Lane was directly influenced by key figures in the movement, particularly List. Wotansvolk, a Wotanist organization founded by Lane and his associates to promote racist paganism, quoted List’s writing heavily in its publications. In the introduction to the Wotansvolk pamphlet Creed of Iron, Lane revisits many of the manifesto’s themes through List’s reference to “Nature’s laws.” On the facing page is a photograph of List, with a dedication to “the great Wotanist and Runemaster.”

There are other, implicit relationships between Lane’s thought and that of the Völkisch movement. While swift industrial expansion was not a concern for Lane, its rapid contraction was. He wrote the manifesto sometime in the 1980s, in the wake of abysmal unemployment levels—the worst since the Great Depression—provoked by the decline of U.S. manufacturing. Such economic turmoil informed not only his vilification of affirmative action but also a broader contempt for capitalism, which, in the tract “Revolution by Number 14,” he called a “mindless pursuit of money and pleasure while the race dies.”

In Lane’s “88 Precepts,” capitalist materialism also invariably “leads to the rape of Nature and destruction of the environment,” imperiling the race in the process. As in Völkisch philosophy, nature was a crucial aspect: “The truest form of prayer is communion with Nature.” Lane urged his followers to search out undeveloped spaces where they can experience natural qualities like “strength, peace, and certainty” in order to better connect with their racial heritage.

Further echoing Völkisch thought, Lane viewed Christianity as a threat to a racially differentiated people. Its universalism, which could emphasize racial leveling, was thought to endanger the distinctness of white people, aiding in their genocide. He also embraced pre-Christian paganism as a core aspect of whiteness, going so far as to adopt the name Wodensson, based on yet another name for Odin. Similar to List, he blamed Christianity for engaging in “a thousand-year war to destroy our organic religion of Wotanism” that “murdered every European who would not bow down to Rome and to God’s Chosen People.”

Lane held Jewish people and other “outsiders”—African Americans, LGBTQ people, and feminists who sought control over sexual reproduction and other rights—responsible for these perceived threats to whiteness. The emphases on anti-capitalism, nature, and anti-Christian paganism notably differentiate his writings from older forms of white nationalism in the United States, however. For instance, the Klan, during its heyday in the 1920s and early 1930s, generally viewed capitalism favorably, defined itself through Protestant Christianity, and rarely mentioned nature in its publications.

In The Politics of Cultural Despair historian Fritz Stern argued that the Völkisch indictment of modernity “had some basis in reality.” Industrialization actually destroyed rural spaces, peasants really were crowded into atrocious tenements, and the material demands of capitalism did limit spiritual and intellectual pursuits. Völkisch thinkers translated these experiences of modernity into a threat to their racialized understanding of “Germanness,” using them to mobilize their followers against the “outside” influences they blamed for the upheavals of modern life.

Considering this history, it’s worth asking what the relationship is between our own turbulent modernity and contemporary white nationalism. The modernity of neoliberal capitalism began with the contraction of manufacturing in the United States in the 1970s and is carried on today by reduced opportunities for young people, stagnant wages, stalled gains in life expectancies, and so on. Ecological devastation remains an issue, now coupled with the menace of climate change. That Völkisch thought continues to be influential through Lane’s and others’ writing raises the question of whether its continuing appeal is bolstered by this kind of social instability. Does a romanticized emphasis on folk “traditions” like Wotanism reinforce this appeal? Even for the relatively well-off—like the young, well-dressed demonstrators in Charlottesville—the turmoil of neoliberalism could contribute to a yearning for the apparent stability of a mostly imagined “simpler past.” After all, Völkisch thinkers like Lagarde and List came from wealthier backgrounds, as did most of their followers.

To be clear, asking these questions about the endurance of Völkisch thought does not excuse virulent racism, anti-Semitism, and white nationalism. But such questions offer an important keyhole into understanding contemporary white nationalists through their intellectual roots. That kind of understanding can help in dealing with the ongoing challenges presented by white nationalism.

Explore Fear, the Summer 2017 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.