Dolan Hall at the Walter E. Fernald State School, 2016. Constructed in 1906, Dolan Hall was used as a dormitory for over a century. Photograph by David Whitemyer.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

When Franklin Roosevelt declared war on Japan and Germany in early December 1941, thousands of Americans set down their work and enlisted. In Boston, as in other cities, the exodus included employees from hospitals, asylums, schools, and institutions. Nine miles west of the city, the Walter E. Fernald State School was no exception. Roosevelt had called on people’s “righteous might” to “win through to absolute victory,” and they had listened; at the Fernald, Superintendent Ransom Greene did his best to hide his disappointment.

Greene had spent decades running state institutions for the so-called feeble-minded. Before that, he had been a soldier in the Spanish-American War. During World War I, he was a captain in the medical corps. Greene was no stranger to the idea that sacrifice often follows a call to service. But after sixteen years running the state’s leading facility for the care and treatment of people with cognitive and developmental disabilities, he was also ready to retire. The war stood in his way.

Greene was forced to stay on and meet immediate new demands from a wartime government. On a Saturday in early January 1942, the Fernald received a communiqué from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health titled “DIRECTIONS FROM DEPARTMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH REGARDING ENEMY ALIENS.”

The document cited the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s guidelines for carrying out orders from President Roosevelt to identify and detain German, Italian, and Japanese-born Americans as enemy aliens. It then instructed the school’s staff to restrict the movement of eight Italian-born patients and one Italian American staff person mistakenly believed to be a resident. All of them were now considered enemy aliens of the U.S. government.

The letter is the first ever uncovered that proves people with disabilities who were in the permanent care of the state were specifically targeted as enemy aliens during World War II. It is a perplexing document, demanding the confinement of people whose movements were already restricted. Classified by their supposed mental capacities as “idiots,” “morons,” and “imbeciles,” these foreign-born Americans almost certainly were committed against their will. Most, if not all, would never have had the opportunity to leave the Fernald.

Even today, the eight inmates are denied a certain fundamental dignity. Having been listed as patients at a medical facility, the mention of their names is prohibited in perpetuity by Massachusetts’ strict medical records laws; so is access to their records. Save for the one employee on the list, they are described but not named here.

Little more than fragmentary evidence remains of life at the Fernald School during that time. What is known is that in 1941 the Fernald School had a reputation as a pioneering institution of its kind in America. Its status belied its unappealing appearance: the campus of large brick buildings included dormitories, classrooms, day rooms, and doctor’s offices overfilled with people of all ages and types of ability, living in poor conditions. With nearly two thousand inmates and over a hundred acres of buildings and farmland, the Fernald was poised precariously between needed reforms—which it would have no way of getting during wartime—and chaos. In many ways, it had been too much for Ransom Greene to manage since he first took the job as superintendent in 1925.

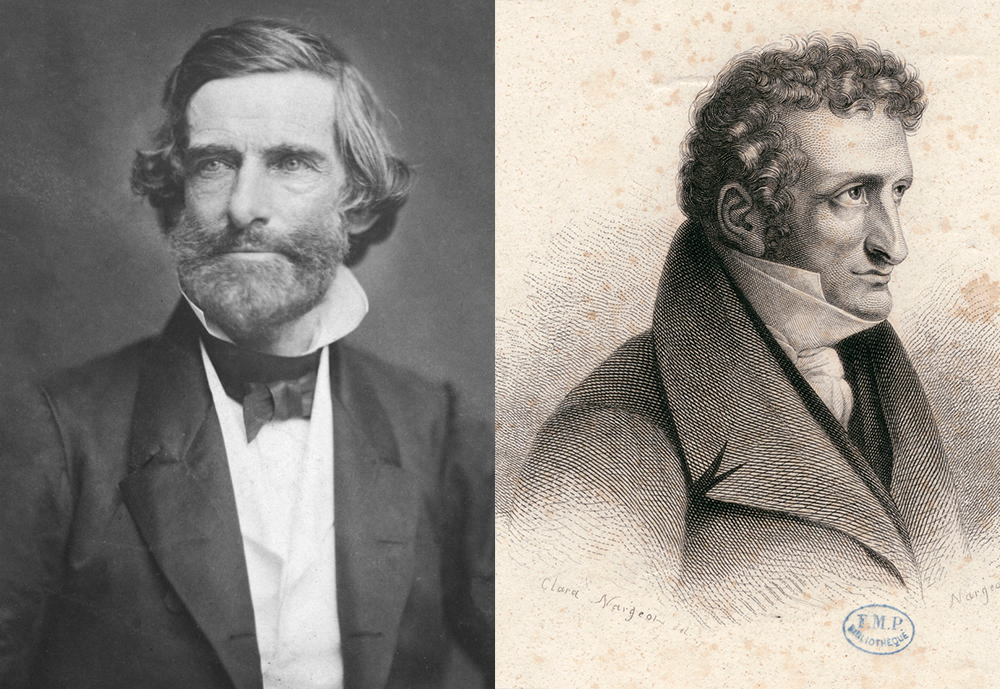

The Fernald School’s roots trace back to the beginning of special education, a lineage that ran from the reformer Samuel Gridley Howe, the school’s founder, to Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, an early nineteenth-century French physician whose treatment of Victor, the “Wild Child” of Aveyron, popularized the belief that seeming “idiots” could learn.

After observing European methods based on Itard’s work, Howe and a group of fellow reformers urged Massachusetts to follow suit. Their Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-minded Youth was the first public institution of its kind in the Americas, founded in 1848 as a small experimental school run by Howe.

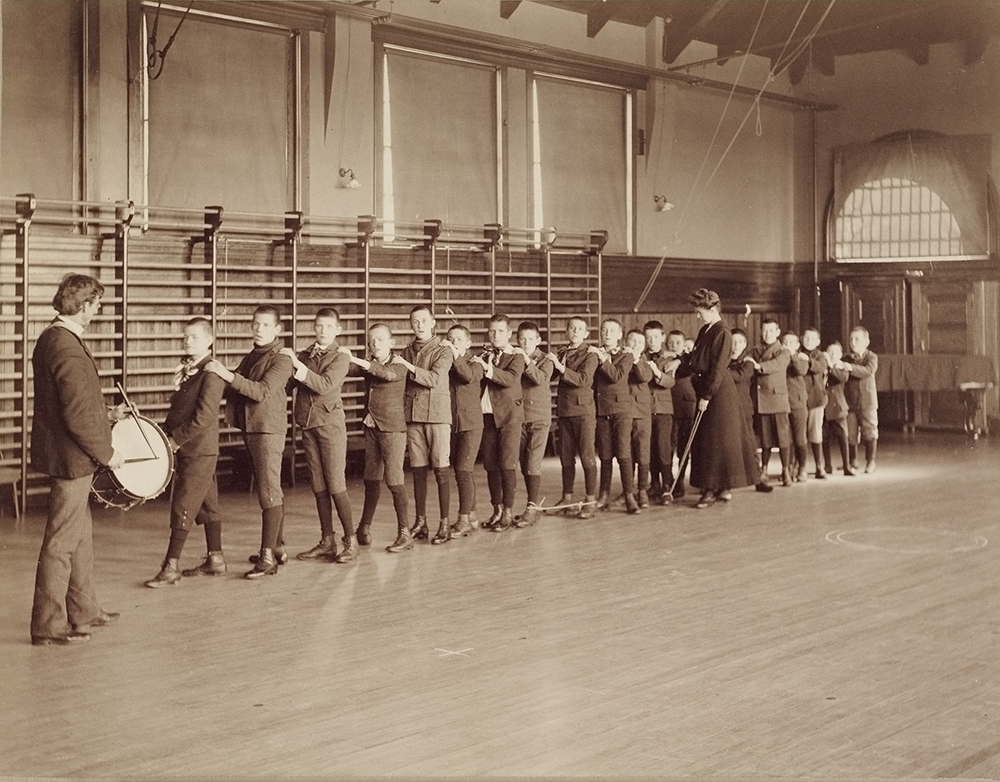

Howe recruited students with mild disabilities and had very specific ideas about how they might improve. In line with Itard’s protégé, Édouard Séguin, Howe believed that many cognitive disabilities stemmed from weakened connections between the senses and the mind. His techniques were designed to enhance those connections through increasingly complex exercises until students could return to their families and to society.

Howe’s successor, Dr. Walter Fernald, had innovative ideas of his own. Fernald moved the school from its aging building in South Boston to the open hills at the edge of the city of Waltham, where a growing population of students took classes in a broad array of subjects. They also farmed, maintained the campus, and even laid the foundations for buildings. A persuasive speaker with seemingly limitless energy, Fernald evangelized for his methods, driving himself to exhaustion by speaking at conferences across the country, urging civic advocacy groups to push legislators for more education and more institutions, and leading visitors from as far away as Australia and South Africa on tours through the school. In Massachusetts, Fernald also helped spawn a handful of new state schools modeled after his own. Between his work and Howe’s legacy, the school provided a way for educators to relate ideas about intelligence to practical education. They linked specific pathways of learning to students’ mental ages, and their institution attained a global reputation as a leader among institutions for people with disabilities.

Over time, however, Fernald embraced his colleagues’ fears about the potential for dangerous tendencies among the students—termed “the menace of the feeble-minded” by Charles Putnam in a 1913 pamphlet—should they return to society. Walter Fernald stopped releasing his pupils. The school grew dangerously overcrowded. When Fernald died suddenly in 1924, he left Greene with a massive institution at Waltham filled with inmates, not students, as well as a thousand-acre work colony in the town of Templeton, fifty miles west. What began with a few children in 1848 now housed over a thousand people of all ages. That’s when the school was renamed the Walter E. Fernald State School.

Variously referred to as students, patients, and (hereafter in this essay) inmates, people ended up in the Fernald by way of the courts, public hospitals, and orphanages, committed by others outside their control. Some were abandoned by parents or left by overwhelmed distant relatives. Despite its caring reputation, the school was soon indistinguishable from most overcrowded public institutions. Funding was tight and wait lists were long. The state often forced the school to take in certain people, even if it was at capacity. Beds were so tightly packed there was no space between mattresses. Without adequate staffing and funding, people were locked in rooms and left to stand naked for hours each day alongside others unable to control their bowels rather than bother with changing soiled clothes. People with only mild impairments, such as altered speech caused by slight hearing impairments, could spend a lifetime strapped in chairs if they fought back against their incarceration. Epidemics ran through the wards. Some inmates had no disabilities at all, and it is likely that some of the Italian “enemy aliens” were among them. Born in 1910, one woman on the list stands out: she was a married naturalized citizen with an eighth-grade education.

In Massachusetts, Fernald had created a network of ways to commit individuals against their will. And while he later came to reject his own effort to keep people confined within the institution, his experiment with incarceration created a network of judges, doctors, teachers, and school officials supported by various forms of legislation. His efforts, and those of his fellow superintendents, gained broad social support from citizens who pushed the medical bureaucracy to favor forced institutionalization by default. With few means for patients to object, the school’s population rose whether Greene wanted it to or not. Further driving the increase were societal concerns about immigrants. Year after year, Greene received requests from the U.S. Labor Immigration Service to tabulate the number of immigrants at his institution. The service was acting on growing fears among the public that immigrants needed to be studied, watched, and contained by the government at all times because of the belief that they were carriers of disability and disease, which in turn were thought to be tied to poverty and crime. Keeping people with disabilities out of the country had been part of immigration law for decades, but just before Greene took over, the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act added highly restrictive quotas for the first time.

Fear of immigrants was fueled by the eugenicists, who believed that “poor breeding” between supposedly unfit individuals propagated the spread of so-called defective delinquents—a term coined by Fernald—from generation to generation. In part or in whole, their beliefs became central to American ethnic nationalism, just as they later were for the Nazis.

In 1927 eugenics supporters gained legal support when the Supreme Court ruled in Buck v. Bell that forced sterilization of people with disabilities was permissible. In the infamous words of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., author of the court’s majority opinion, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Greene was thoroughly unconvinced. “I have done my fair share of studying the subject of eugenics,” he wrote in 1934, “and have come to the conclusion that inasmuch as the biologists and the best in the country will set no standards, I would be assuming a great deal to take a stand or establish a standardization of what is heredity and what may be environmental.”

He was surrounded by citizens who did not agree. One was the Reverend Kenneth C. MacArthur, the influential minister of a Baptist church in Sterling, Massachusetts. MacArthur claimed he had observed the principles of eugenics at work in everything from statistics to the cattle in his own stockyard. He presented his beliefs as moderate, proscience, proreligion, and, like many eugenics supporters, antiwar. “One of the worst things about war,” said MacArthur in 1930, “it kills off so many of the physically fit and leaves the physically unfit.”

During the Great Depression, incarceration continued at a rapid pace, but funding for institutions, including the Fernald, did not. When the institution closed in 2014, there were multiple staffers for each resident. In the decade from 1930 to 1940, the staff-to-inmate ratio at the Fernald School never dipped below one employee for every five inmates.

Approaching retirement, Greene was hopeful that a qualified successor would bring improvements. In 1938 he hired Dr. Malcolm Farrell. Young and expert, Farrell came from the state’s newest institution, an asylum across the road called the Metropolitan State Hospital, where he had served as senior physician. Farrell realized the Fernald required reforms. He hoped to create smaller residential facilities for people with disabilities at the institution, with the school acting as a coordinating center for community resources, a precursor to the deinstitutionalization that began nationwide in the 1960s. He also wanted to get out in front of the eugenicists, conducting original scientific research at the institution for the first time in decades. The Depression was waning, and a series of scandals about underfunding seemed to hint at a coming era of relief and financial support for the faltering institution. Then came the war. Farrell left for the Surgeon General’s Office in Washington, DC, and Greene continued on alone.

Americans’ feelings toward immigrants had only hardened throughout the Depression. The Smith Act, passed in 1940, required all aliens to register with the government and be fingerprinted. The following year, the government created an immigrant custodial detention program.

Immigrants like Antonio Cimino would have had to report to the basement of the Waltham post office to be fingerprinted and registered. The fifty-six-year-old Italian-born naturalized citizen was married and working as a clerk in a grocery store. In return for registering, he wasn’t detained, but sometime in the next year, he took a job at the Fernald, ending up on the list of enemy aliens that went to Ransom Greene.

The eight Italian-born inmates at Fernald could not leave unless paroled, which was forbidden by the order. Even brief travel required seven days’ notice and the FBI’s approval—a bizarre bureaucratic indignity, given that the inmates had been committed and had no ability to leave anyway.

In time these eight were not alone in falling under the government’s surveillance. Beginning in May 1942, five months after the communique was issued, and lasting the duration of the war, the FBI requested fingerprints of every inmate. Every year, Greene sent the same cover letter with the fingerprints stating, “These prints were all taken from mentally deficient children in the institution, some of whom were uncooperative.” The word children likely referred to the perceived mental age of the inmates. Of the Italian inmates, the 1940 census indicates those ages via grade levels, under a column titled “Education.” For one thirty-five-year-old man, it says, “Fourth grade.” For a thirty-year-old woman, “First grade.” For another, a forty-five-year-old man, “None.”

The stories of the “enemy aliens” are difficult to separate from the quiet collapse of the Fernald overall. They shared a status with the Fernald School as a whole during wartime: both were set up for carefully contained neglect, so long as it happened out of sight and out of mind.

In 1942 Greene’s staff left in droves to serve in the war. By the end of the year, over 50 of the school’s 320 positions were vacant. When vacancies were filled, Greene was appalled by the newcomers’ lack of qualifications. That year, for the first time since 1848, the Walter E. Fernald State School did not file an annual report, a practice it did not resume until 1952. The board of trustees stopped meeting. Correspondence from Greene to the small staff at the school’s farm colony at Templeton, where one of the Italian-born inmates lived alongside other adult men without modern heat or electricity, appears to have ceased altogether.

Greene tried to lessen pressure on the institution by paroling patients out to local companies. High-functioning inmates worked for private companies outside the institution, returning to the school at night. Their pay was managed by employees of companies and the school. It was a haphazard effort at best, and it also had little if any impact on declining conditions on the campus. In fact, some of these day parolees went missing. It was later suggested that many had been enslaved by their employers, who made them work and then stole their wages.

In June 1943 H.H. Ramsay, superintendent of the Utah State Training School in American Fork, wrote to Greene to ask if two of his employees could visit classes at the Fernald in order to learn what the leading institution in the country was doing to teach its patients. Greene warned him off:

I will assure you that we will be very glad to have Mrs. Meda Hunsaker and Mrs. Jessie Wadley visit our institution but if the visit is for the purpose of observation of our teaching, it will be absolutely futile. Our head teacher, as well as our force of teachers, will be away and there will be no school activities.

As a matter of fact, I have but one woman physician left on my staff. I am so depleted in my staff in the total personnel that I am one hundred and forty-one short today. There would be no one who would either have time or ability to furnish information or observation in any training or teaching facilities.

A year later, it was worse. Replying to a questionnaire from the Social Security Board in Boston in 1944, Greene wrote:

Your questionnaire can not be answered because the bulk of it does not apply, therefore I will tell you the following as regards to my situation as superintendent of a large institution.

I have six physicians and need eleven. One of the six is being retained beyond retirement age. I am a Veteran myself and should have been retired three years ago.

This morning, I have 176 vacancies in positions in this institution. Custodians, gardeners and ward boys do not apply to this institution. I have authority to employ twelve nurses but I can not employ any…

I could go on and on with the employment situation if anybody is interested. As near as I can make out, nobody is.

Yours Sincerely,

Superintendent

Malcolm Farrell returned in 1945, giving Ransom Greene his longed-for retirement. In a May 6, 1946, letter to Clifton Perkins, the commissioner of the Department of Mental Health, Farrell wrote that conditions at the institution were “not up to the standard that it should be.” Where the school had once farmed a great deal of its own food, there were now shortages of even the most basic items and a reliance on canned items, such as tomatoes. The patients who had not been paroled were severely disabled, he wrote, and their living conditions “seriously overcrowded.”

When Farrell insisted that the trustees begin meeting again, he took them on a tour through two of the worst buildings of the thirty-five on campus. He learned, as he informed Perkins in the letter, that “one man, whose term expires next month, had never been inside either of these buildings during his entire service as a trustee.”

Governor Leverett Saltonstall stepped in and pledged money and reforms, but Perkins, Farrell, and their colleagues shared a sense that no quick fix was possible. From 1944 through 1946, over half of the doctors in the Department of Mental Health resigned, enticed by the higher pay of private practice. The booming postwar economy meant that public institutions—from the Metropolitan State Hospital asylum across the road to the network of schools created at Walter Fernald’s urging—would be underserved and overcrowded.

Farrell proposed bringing doctors back by creating a board certification for the care of people with cognitive disabilities. Doctors would have to work in institutions for a period of time and would receive the distinction of being board-certified in return. Harry Storrs, superintendent at New York’s Letchworth Village institution, urged Farrell to wait for the economy to backslide instead. “When people are not as flush with their money,” he wrote, “these fellows in the private practice of psychiatry, in my opinion, will find it pretty hard to make a living and, then, I feel competent young men will again be available for institutional staffs.”

Gale Walker, superintendent of the Polk State School in Pennsylvania, was less hopeful:

I believe the Schools for the feeble-minded have fallen on evil days partly through lack of clear understanding of our Governmental governing bodies, partly through our own apathy and weakness in our Institutions, and partly through our affiliation with our stronger sister organization, the Psychiatric Society…

You state that mental deficiency is a step-child of psychiatry. I feel it is some type of an illegitimate offspring. I think the continued association has been increasingly handicapping as the structure of psychiatry itself has become increasingly more definite. I have reason to feel that the person with some psychiatric training may stay out of the mental deficiency field because of fear that he is getting away from the real main line of psychiatry.

Farrell lost the battle to create a separate, respected specialization for his profession, along with his hope to deinstitutionalize the Fernald in his own lifetime. Instead he was forced out, his name tarnished by scandals over the poor conditions that prompted a court takeover in the early 1970s, followed by deinstitutionalization. Long after his death, it was found that his research program had included human radiation studies on boys at the school in the 1950s. A 1970s-era building on the abandoned campus bears Farrell’s name, encircled by ramps and railings, the lights on at night. The boys’ dormitory, built during Walter Fernald’s time, sits open atop a hillside, defaced by ghost hunters, thrill seekers, and neo-Nazis who sneak in to celebrate the worst of what was done there.

The nine people listed in the enemy alien letter lived long lives, and most appear to have died outside of Fernald. It is unclear whether they ever knew of their dual imprisonment.

Richard Howick contributed to this article.