English settlers faced with unfamiliar landscapes and previously unknown plants and animals in the Americas had to find terms to name and describe them. They sometimes borrowed words from Native American languages. They also repurposed existing English words and invented new terms, as well as keeping words that had become archaic in British English. As non-English-speaking immigrants began to arrive during the eighteenth century, they accepted words from those languages as well. By the time of the American Revolution, English had been evolving separately in England and America for nearly two hundred years, and the trickle of new words had become a flood.

Corn offers an example of how English words evolved in America. Before 1492, the plant that Americans call corn (Zea mays) was unknown in England. The word corn was a general term for grain, usually referring to whichever cereal crop was most abundant in the region. For instance, corn meant wheat in England, but usually referred to oats in Ireland. When American corn came to Britain, it was named maize, the English version of mahiz, an Indigenous Arawakan word adopted by the Spanish. When the first colonists encountered it in North America, however, they almost always referred to it as corn or Indian corn, probably because it was the main cereal crop of the area.

Both John Smith and William Bradford nearly always called it corn in their writings, only using maize occasionally. Smith mentioned corn frequently in his reports of his dealings with the Powhatans. In 1607, he wrote, “Our provision being now within twenty days spent, the Indians brought us great store both of corn and bread readymade.” He also used the same word to refer to the seeds brought from England: “Our next course was to turn husbandmen, to fell trees and set corn.” The seeds in question were probably wheat (or at any rate, not maize), suggesting that Smith still used corn as a general term for any staple cereal crop.

Corn was central to survival for the English settlers, so corn terms soon proliferated. In Noah Webster’s 1828 dictionary, the entries under corn cover two columns. These include the terms corn basket, corn blade, corn cutter, corn flour, corn field, cornmill, and cornstalk, among others. Webster defined corn the way the English do, as a cover term for any grain, but noted, “In the United States…by custom it is appropriated to maize.”

Other corn-related words that came into the language early on are succotash, hominy, and pone, all from Algonquian languages. In his narratives, Smith referred to “the bread which they call ponap,” and also described “homini” as “bruised Indian corn pounded and boiled thick.” The terms roasting ear, johnnycake, and hoecake (both cakes made from cornmeal) were all in use by the eighteenth century.

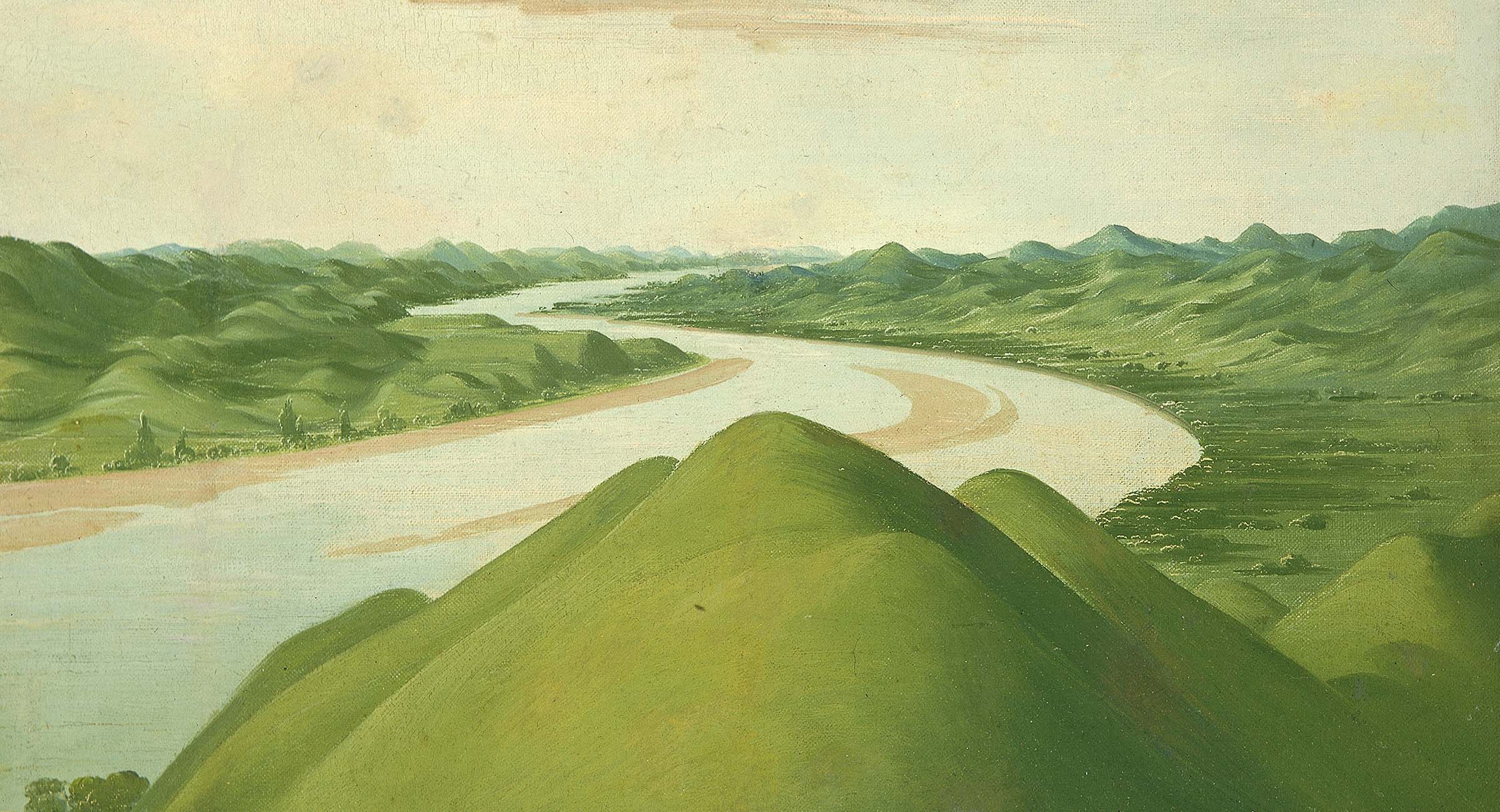

Much of the landscape of North America was new to the English, so many early word inventions applied to the natural world. Often these simply combined a noun with an adjective: backcountry, backwoods (and backwoodsman), back settlement, pine barrens, canebrake, salt lick, foothill, underbrush, bottomland, cold snap. Plants and animals were similarly named, for instance, fox grape, live oak, bluegrass, timothy grass, bullfrog, catfish, copperhead, lightning bug, garter snake, and katydid (a grasshopper named for the sound it makes). All were part of the vocabulary by the mid-eighteenth century. Other descriptive landscape names included clearing, rapids, and bluff.

Bluff has the distinction of being the first word with a changed meaning to be noticed and criticized by a visiting Englishman. Writing about Savannah, he reported, “It stands upon the flat of a hill; the bank of the river (which they in barbarous English call a bluff) is steep and about forty-five feet perpendicular.” A bluff in England denoted a high but rounded shoreline, while in America it was used to describe steep cliffs.

Americans repurposed other English words as well. For example, bug, which meant a bedbug in England, broadened to cover any insect, and sick, which referred specifically to a digestive upset, became a general term for any illness. What the British called timber, Americans called lumber. (In England, lumber is old, discarded furniture and other items of the sort usually found in attics.) Americans called a shop a store, as in grocery store (perhaps from an archaic use of store to mean an abundant supply) and said fall for autumn. Fall was short for fall of leaf, once a common phrase in England, but becoming obsolete by the eighteenth century. Americans also said mad for angry, another English usage that died out in the old country.

The expression I guess, meaning that one supposes or agrees, is often used to stereotype Americans in British books and movies, but it was current in England during the seventeenth century, and was no doubt imported by the first North American settlers. Later, that usage went obsolete in England but remained popular in America. An early in-print example comes from the Massachusetts Spy newspaper for February 2, 1798, “I guess my husband won’t object to my taking one if they are good and cheap.” During the nineteenth century, it was a regionalism specific to New England, although it later became common everywhere. To quote the Massachusetts Spy again, for November 8, 1815, “You may hear [a Southerner] say ‘I count’—‘I reckon’—‘I calculate’; but you would as soon hear him blaspheme as guess.”

Americans sometimes misapplied names to animals and plants that looked like English species but were not really the same, such as rabbit for American hares, robin for a kind of thrush, butternut for a variety of walnut tree, and cottonwood for a kind of poplar.

Several words for bodies of water changed meanings between the old country and the new. In England a pond is artificial, but in America it is natural. Creek in British English refers to an inlet from the sea, while in American English it describes a tributary of a river. An English watershed is a line or ridge separating the waters that flow into different drainage areas, but in America it’s a slope down which the water flows, or the catchment area of a river. Americans added the meaning of a small stream or brook to branch and said fork to refer to one arm of a river as well as a fork in the road.

English speakers also adopted words from other colonial countries. The language that influenced early American English the most is Dutch. In 1609, shortly after the Jamestown colonists ventured into Virginia, an Englishman named Henry Hudson, who worked for the Dutch East India Company, landed on the island of Manhattan and claimed it and the surrounding territory for his employers. By the 1620s, New Netherland was the site of several Dutch settlements.

New Netherland changed hands in 1664, part of the English spoils of the Anglo-Dutch war. King Charles II handed it over to his brother the Duke of York, who renamed it New York. A substantial Dutch population remained, however, still adhering to their own customs and speaking their own language. Dutch could be heard in both New York and New Jersey until the late nineteenth century. Meanwhile, English speakers adopted several Dutch terms.

These include food words such as coleslaw (Dutch for cabbage salad), cookie (Dutch for little cake), cruller, and waffle. The words scow, spook, and stoop (the landing of the front steps) also came into the language in the eighteenth century. Dope, which is Dutch for a sauce, originally named a preparation of pitch and other ingredients that was applied to the bottom of shoes for smooth walking over softened snow. It had taken on its drug meaning by the 1870s. Boss, originally werk baas, or “work master,” was used both to mean the man in charge and to refer to a master craftsman, for example, boss carpenter. Bushwhacker, from a Dutch term meaning forest keeper, made its first appearance in print in 1809, in Washington Irving’s comic novel A History of New York, written under the pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker. He describes a gathering of prominent Dutch settlers as “gallant bushwhackers and hunters of raccoons by moonlight.”

Yankee is also almost certainly a Dutch contribution. Various theories have been suggested for the word’s origin (for instance, that it’s a Native American mispronunciation of English), but the most likely one derives the word from Janke (pronounced “yan-kuh”), a diminutive of John that translates as something like “little John.” It may have been inspired by John Bull, a popular nickname of that time for a typical Englishman. Americans were “little John Bulls.” At first Yankee referred only to New Englanders, but by the time of the Revolution, when the song “Yankee Doodle” was first heard, the British applied it to all Americans. During the Civil War, Southerners adopted the term to apply to anyone from a Union state.

Excerpted from The United States of English: The American Language from Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century by Rosemarie Ostler. Copyright © 2023 by Rosemarie Ostler and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.