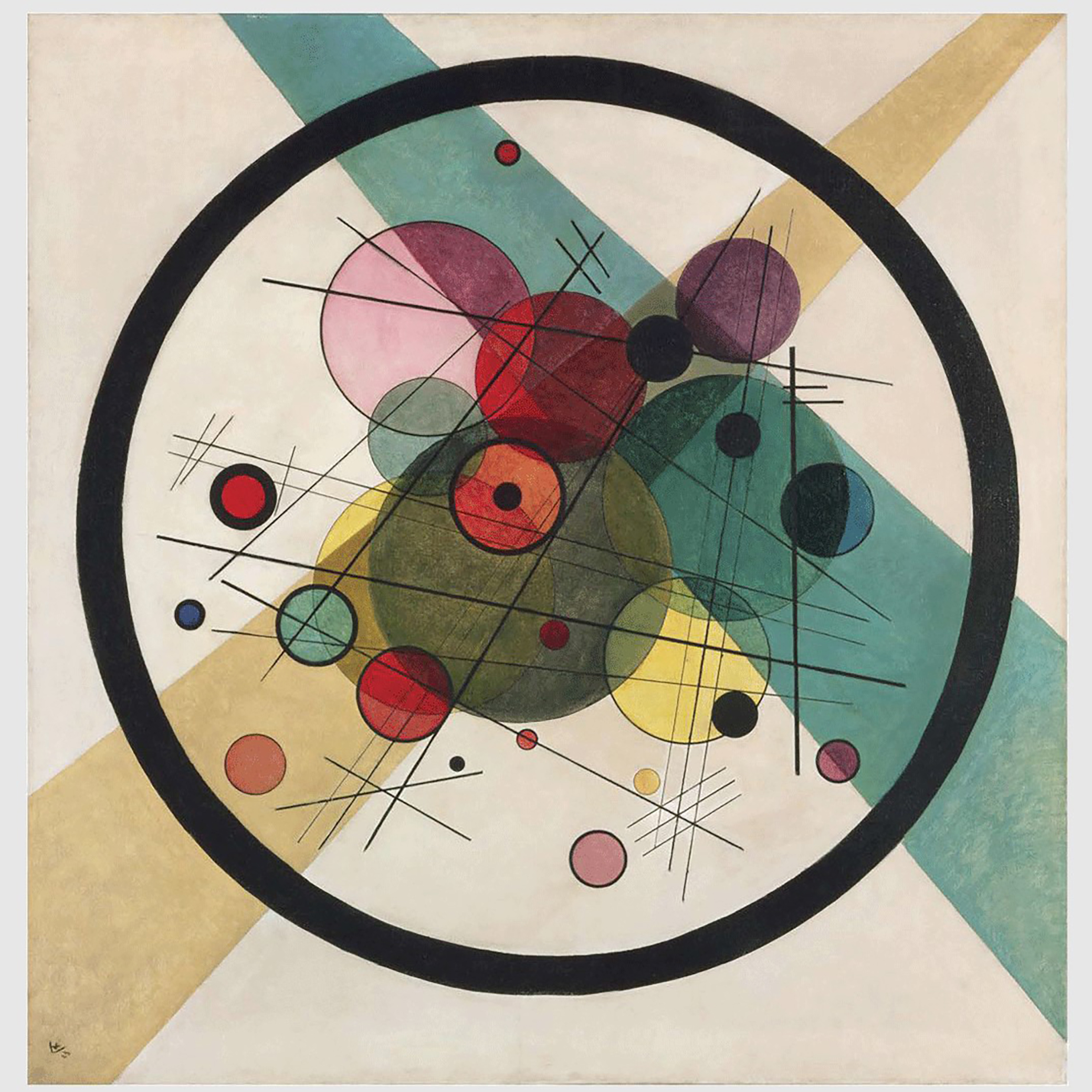

Circles in a Circle, by Wassily Kandinsky, 1923. Wikimedia Commons, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“The life of man is a self-evolving circle, which, from a ring imperceptibly small, rushes on all sides outwards to new and larger circles, and that without end.”

―Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Circles”

What is gone is gone always. Or so we tell ourselves, melancholy materialists who have seen the disappearance of so many things we loved: people, objects, eras, ideas. Waldo, of course, was less certain about these matters. It was in “Nominalist and Realist” that he seemed to deny the reality of death itself. “Nothing is dead,” he insisted. “Men feign themselves dead, and endure mock funerals and mournful obituaries, and there they stand looking out of the window, sound and well, in some new and strange disguise.”

He wrote these sentences (or at least published them) in 1844. He was still reeling, in other words, from the death of his son. Was he soothing himself with the idea that he would someday see Little Waldo’s eyes peering out at him from another face? Or was this a tribute to the power of memory, wrapped in another of his deadpan metaphors? Or simple denial?

His conviction that nothing truly ended—that extinction was illusory—ran deep, and he never expressed it more beautifully than in “Circles,” from his first collection of essays. “Our life is an apprenticeship to the truth, that around every circle another can be drawn; that there is no end in nature, but every end is a beginning; that there is always another dawn risen on mid-noon, and under every deep a lower deep opens.”

His argument went far beyond the question of mortality. Regeneration was the engine of the universe. “Thus there is no sleep,” he wrote, “no pause, no preservation, but all things renew, germinate, and spring.” Nor did human beings live in straight lines, but in a kind of glorious circularity. (In a moment of self-mockery, Waldo actually referred to himself as a “circular philosopher.”) Has he not encouraged us, then, to turn directly from his death—with his body still warm—to his birth?

He entered the world on May 25, 1803. This was in Boston, the city he would later condemn as a necropolis of dead ideas and faint hearts and mercantile mildew. But what he saw as a child was very different. The yellow wooden house on Summer Street sat on two acres of land, girdled with spreading elms and Lombardy poplars and with a view of the harbor down below. All around were leafy estates and open, cow-dotted pastures. It was a small bucolic paradise within the city limits, and probably defined Waldo’s notion of tranquility forever.

Not that all was tranquil within the Emerson household, at least for Waldo. The third son in a rapidly growing family, he seemed to draw his father’s ire or indifference from the time he was born. In his diary, the Reverend William Emerson jammed his arrival between a host of social engagements: “This day also, whilst I was at dinner at Governor Strong’s, my son Ralph Waldo was born. Mrs. E. well. Club at Mr. Adams’.” He frequently carped about the boy’s educational progress, complaining that he was “a rather dull scholar”—when Waldo was all of two years old! A few months later, with the boy just shy of three, his father continued in the same sniffy vein: “He cannot read very well yet.”

He was also concerned, over the next few years, that Waldo spoke too freely, wolfed down his food, and got himself into mischief. It was to be hoped, wrote this flinty paterfamilias, that Waldo would soon be “resigning his impetuosity to younger boys.”

There is a puzzle here. In so many ways, William Emerson should have been a role model for the young Waldo, and for the man he came to be. They had a lot in common. William was also the son of a revered clergyman who had little desire to follow his father into the ministry. After his ordination, when he found himself tending the flock in the tiny town of Harvard, Massachusetts, he was undoubtedly a modernizer and quasi-maverick.

He asked, for example, to retire the old Calvinist custom of “making public confessions for the sin of fornication,” and was soundly shouted down. He also offered to accompany the choir on bass viol—a smaller sibling of the cello that was increasingly employed in colonial churches for its deep sonority, and because it kept the wobbly-pitched singers in tune. Again, he was voted down.

The village, which just a generation earlier had stoned a congregation of Quakers, was having none of William Emerson’s Unitarian-leaning bells and whistles. He felt besieged, and was regularly reviled at town meetings. His position in Harvard, he wrote a friend, isolated him “from the intercourse of all humanized beings.” Meanwhile, his attempts to mollify his flock—he sold the bass viol—got him nowhere. He dreamed of fleeing the town to establish a post-Puritan church “in which there was to be no written expression of faith, no covenant, and no subscription whatever to articles, as a term of communion,” where he would simply “administer the rituals of Christianity to all who would observe them.”

Salvation finally arrived in the form of an offer from the First Church in Boston, which happened to be the oldest in America. There he was no longer a clay pigeon for a bunch of cranky Calvinists, but a pillar of Brahmin society. He sported a gold-topped cane and loved to show off his elegant ankles in their black stockings. He was also heavily involved in literary culture. The possessor of a frisky prose style—at times it suggests a tamer, less dirty-minded Laurence Sterne—he spent several years running the nation’s first literary magazine, The Monthly Anthology (which would eventually morph into the North American Review). Meanwhile, having established a small public library in Harvard, he nowbecame the motivating force behind the Boston Atheneum’s collection. Shouldn’t this double-decker paragon, with one foot in the pulpit and the other in literature, have inspired his son?

There were a few flies in the ointment. William Emerson became a more cautious and conservative man as he ascended the social ladder. Having shown at least some radical tendencies during his miserable exile in Harvard, he quickly became part of the Establishment—a fact that rankled Waldo as a young adult, although it would not have bothered him as a child. More to the point, William’s glory days as a wig-wearing ecclesiastical peacock were sadly short-lived. The family moved to Boston in 1799. In 1808, he suffered a severe lung hemorrhage, then spent the next three years struggling with tuberculosis and stomach cancer. These dual maladies, which finally killed him in 1811, must have cast a pall over the entire household.

Yet none of this completely explains Waldo’s lifelong hostility toward his father, which took the form, as he grew older, of flagrant erasure. Asked later in life for memories of William Emerson, he insisted that there were only two. He was nearly eight when his father died—old enough to have retained at least the bare bones of a filial narrative. Instead, there were two isolated anecdotes, the first involving the treatment of Waldo’s eczema (then known as salt rheum):

I know the doctor had advised him to have me go into the salt water every day because I had the salt rheum and he used to take me himself to the Bath-house. I did not like it, and when in the afternoon he called me I heard his voice as the voice of the Lord God in the garden, and I hid myself and was afraid.

Pain, of course, is the first association here: the salt working its excruciating magic on the boy’s open wounds. But the phrasing in the second half is straight out of Genesis. The voice of the Lord God in the garden, let’s recall, is what precedes nakedness, ruin, the expulsion from Eden. Waldo could hardly have cast his father in a more punitive role.

The other anecdote concerned his father’s funeral. This affair took place on May 16, 1811, and featured a lengthy procession of mourners loaded into more than fifty coaches. The two oldest Emerson boys marched directly behind the hearse, and while they must have been impressed by the solemnities, the elderly Waldo, recalling the event for his daughter, stressed that he wasn’t sad. Indeed, Ellen wrote, “he used to smile as he recalled his delight in that funeral.” It’s absurd to expect children to feel the appropriate emotions (whatever that means) at such an event—they are old hands already at sublimation, and are most likely to shunt their sorrow elsewhere. Yet Waldo’s delight, decades after the fact, smacks just slightly of dancing on the grave.

So does his habit, in his twenties, of tearing the pages out of bound volumes of his father’s sermons or notebooks, then using the binding to house his own compositions. In a family less devoted to the written word, this might have qualified as Yankee thrift—a slightly perverse sort of virtue. Among the Emersons, it was sacrilege, even if nobody noted it as such. Nor did Waldo, in his mellow old age, desist from this patricidal recycling. On one occasion late in the game, ripping the used pages out of an old notebook of his father’s, he left the stubs throughout, some of them still covered with fragmentary scribbles.

Of course, he had already passed judgment on whatever was contained in those volumes, declaring in his journal that between 1790 and 1820, certainly the heyday of the Reverend William Emerson, “there was not a book, a speech, a conversation, or a thought” in the state of Massachusetts. Why save the mementos of such a wasteland, over which his father had so conspicuously presided?

I don’t mean to stuff Waldo and his father into an Oedipal pigeonhole. But there is a mystery at the heart of that relationship, a friction and sharp sense of disappointment that is hard to ignore. Sons imitate fathers. Sons also struggle mightily, when the time comes, to differentiate themselves from those enormous and engulfing figures. Fathers, meanwhile, feel the draft of time on the back of their necks—the slight coolness of age and obsolescence—and sometimes they blame their sons.

There is, in other words, plenty of room for hostility. Much of that hostility is never expressed directly. It takes the form of slights, omissions, misunderstandings, betrayals: the emotional equivalent of paper cuts, which may nonetheless leave the relationship in anemic shape.

What stops the bleeding is the other elemental fact: that fathers and sons tend to love each other. The attachment is so deep, the recognition so mutual. You are approximations of each other, two versions of the same human being who happen to occupy different spots on the chronological continuum, sharing perhaps a nose and a funny gait and a widow’s peak, the tossed salad of DNA making you different enough to view your sameness with real, joyful astonishment, that being the rough definition of love between a father and son. This eerie and beautiful identification is what supercharges so many other emotions: pride, sadness, loyalty, rage. It also, over a lifetime, puts to bed so much of that original, almost mythological hostility. Only Saturn devours his undoubtedly delicious sons. The rest of us, looking back on all the thoughtless things we said and the pain we never meant to inflict, eat our words instead.

But not in Waldo’s case. William Emerson died young, and the conflict between them was set in stone—there could be no armistice between this father and son, no loving recognition of their likeness. Waldo erased the man from his memory, pillaged the written record of his life and replaced it with his own.

Indeed, he began his career as a writer, in Nature, by impugning the age for its filial devotions: “It builds the sepulchers of the fathers.” His great project, from the very start, was to cut himself loose from the past—from the demoralizing burden of his (like it or not) patrimony. I don’t think this is accidental. He hated the distant figure of William Emerson and disdained to build him a memorial. Yet he couldn’t help but note, in that same book, that the divine spirit almost always came in a paternal package: “Man in all ages and countries, embodies it in his language, as the FATHER.” The heart forgives, even for a moment, what the mind cannot.

Of course, Waldo had a mother, too. She was Ruth Haskins Emerson, universally admired for her calm, piety, and grit—especially after her husband’s death, which left her a pauperized widow with five sons to raise. She supplied at least some of the warmth that William Emerson had withheld. Yet her parental style was also straight out of the Calvinist playbook. Pleasure was kept in studiously short supply. When the infant Waldo sucked his thumb, a gratification-denying cloth mitten was sewn onto his nightgown. Breakfast consisted of toast, but no butter. The young children were dressed day and night in yellow flannel. Mary Russell Bradford, who lived with the family as a babysitter for several years starting in 1806, clearly viewed this last austerity measure as a bit much. (“I did not think it pretty enough for the pretty boys,” she later recalled.)

The brothers were also kept on a short leash. When snow covered the sloping pasturage around the house, sledding was forbidden. In all seasons, Waldo was warned against mingling with his peers from Windmill Point and the South End, who frequently swarmed down the dirt road on their way to some lively kicking and punching on the Boston Common. Sometimes he would wander around the wharves and pick up shells, stones, and gypsum, which gave off a luminous glow when he rubbed two pieces together in a dark closet. But the magic, crucially, took place indoors—within the walls of the educational hothouse on Summer Street.

The Emerson boys, with allowances made for Bulkeley, were expected to be prodigies of learning. “They were born to be educated,” declared their aunt Mary Moody Emerson, who monitored their reading and once berated the young Waldo for checking a novel out of a circulating library. “How insipid is fiction to a mind touched with immortal views!” she fumed.

It was never too early to expect academic miracles, as William Emerson had intimated more than once. When Mary Russell Bradford put Waldo to bed as a child, he would dutifully intone the Lord’s Prayer, and also some of his favorite set pieces, including David Everett’s “Lines Written for a School Declamation.” Everett, a newspaperman who collected his prose in something called Common Sense in Dishabille, had written the poem for a seven-year-old. Waldo was likely quite younger when he recited this perky anthem to precocity:

You’d scarce expect one of my age

To speak in public on the stage,

And if I chance to fall below

Demosthenes or Cicero,

Don’t view me with a critic’s eye,

But pass my imperfections by.

It’s a hilarious picture: the little orator in his yellow flannel, declaiming to a teenage girl. Sometimes he also recited a poem about Benjamin Franklin, or the dialogue between Brutus and Cassius in the first act of Julius Caesar. Heady stuff, you might think, for a five-year-old with a superb memory. “Men at some time are masters of their fates,” I imagine him piping up, perhaps in a sleepy tone. “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars.” He would include the entire dialogue, more than seventy years later, in an autumnal anthology he called Parnassus. But even as a child, he was doubtless storing up silent lessons in fate and freedom, not to mention the mouth-watering music of Shakespearean diction, which he may not have fully understood.

Except that he probably did. There really was no sense, in a family like this one, that children were different from adultsand might benefit from a separate intellectual diet. The Victorian notion of the child as a vessel of innocence was still some distance down the road. Wordsworth had already declared his own childhood a prelapsarian wonder (“Heaven lies about us in our infancy!”), but none of that penetrated the yellow house on Summer Street. There, John Locke was a more likely guide to parenting. Locke’s pedagogical treatise, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, had been published in 1693, more than a century before Waldo’s birth. Yet it had a lengthy vogue, both in England and abroad. It stressed the importance of tamping down infantile appetites, very much up Ruth Haskins Emerson’s alley. Locke also described the child’s mind as a blank slate—as “white Paper, or Wax, to be molded and fashioned as one pleases.”

In the Emerson household, those blank slates got a real workout. Life was an orgy of reading for the young brothers. They were pelted with texts like John Flavel’s On Keeping the Heart, a Puritan guidebook to a sound relationship with God, and Charles Rollin’s Ancient History, a multivolume monster frequently read aloud by the boys. Waldo also cut his teeth on Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the Poets and, once he began attending the Boston Latin School in 1812, Jacob Cummings’s An Introduction to Ancient and Modern Geography, whose globe-trotting author insisted that it would “not be profitable to confine the young mind long to any one part of the earth.” As adolescents, the brothers already knew Alexander Pope and Thomas Gray well enough to produce decent parodies of both.

There was also John Mason’s A Treatise on Self-Knowledge, in which Waldo would have learned that curiosity was a wonderful thing, but only up to a point. “A fatal instance of this in our first parents we have upon sacred record,” Mason warned, “the unhappy effects of which are but too visible in all.” Disobedience, in other words, was only half the problem in the Garden of Eden. It was the desire to know that had ultimately done in poor Adam and Eve. In case the message wasn’t clear, Mason also quoted Corinthians: “Knowledge puffeth up,” a phrase that even a bored child must have relished.

Less weighty material had to be jammed in around the margins. In an 1837 journal entry, Waldo sketched out a domestic scene that was surely a backward glance at his own, complete with the ban on frivolous fiction. He noted the boys “hastening into the little parlor to the study of tomorrow’s merciless lesson yet stealing time to read a novel hardly smuggled in to the tolerance of father and mother and atoning for the same by some pages of Plutarch or Goldsmith.”

Political speech was also fed into the machine. While gathering wood, the boys traded passages by the long-winded Edward Everett (who would later drone on for more than two hours at Gettysburg) and their hero Daniel Webster, who lived in the neighborhood. They meanwhile tackled other languages. By the time Waldo was thirteen and Edward was eleven, they were not only reading French books together but corresponding in Latin.

True to Aunt Mary’s credo, they were all educated to the hilt. Waldo, however, was something different: an inward, dreamy, language-drunk child. Later in life, he recalled sitting in a pew at church and repeating words over and over to himself until they lost all meaning. He made the shocking discovery that almost all bookish children make: words, the key to the universe, are also accidental. “I began to doubt which was the right name for the thing,” he recounted, “when I saw that neither had any natural relation, but were all arbitrary. It was a child’s first lesson in Idealism.”

He was a youthful idealist, then, dressed a little later in blue nankeen. He had the idealist’s tenuous grip on physical reality. The least robust of the Emerson boys, he seldom played, at least in the company of other children. He was not “vigorous in body,” recalled one schoolmate. “He dwelt in a higher sphere,” recalled another. “You have no stamina,” the doctor told him when he was young, a remark that stung him deep into his old age.

Yet he had the strength to separate himself, little by little, from the expectations of his family. His destiny, he declared early on, was to be a poet. I have already mentioned the toddler’s bedtime recitals for his babysitter. This habit seems to have persisted. After the family spent a season in Concord in 1814, and it was time for Waldo to depart the local school, he was asked to mount a barrel in the classroom and deliver a valedictory ode. He happily complied. Years later, he was still reciting scraps of the ode for his children.

There was apparently a similar routine at Deacon White’s general store in Concord. The moment Waldo was hoisted onto a sugar cask like the miniature prodigy he was, he reeled off excerpts from Milton or Thomas Campbell’s “Glenara.” Most likely, he delivered the latter in a faux-Scots accent. Of course it’s funny—the boyish solemnity, the audience there to buy rum, nails, a ball of twine, the little kid going on about “the heath where the oak tree grew lonely and hoar.” Of course Waldo was not the first child to amuse his listeners with such intimations of adulthood, like Brahms played on a pennywhistle.

Yet the moment seems to point backward and forward. Waldo must have seen, many times, his father in the pulpit at the First Church. Such things are etched into a child’s brain. That daunting and distant figure was gone now, buried three years earlier. But surely the sugar barrel was a kind of pulpit, the poems a kind of sermon, the whole performance a gentle parody of what his father had done—and a commemoration. The reader, meanwhile, will see Waldo’s future inscribed in his performance: the adult in the creaky boots, the lectures so numerous that they must have eventually blurred into one. The infinitely private man opening that final door, sharing that final residuum, vanishing into his audience.

This sense of circularity was never far from Waldo’s mind. In 1842, he sketched it out in his journal (with yet another example of his poetry-declaiming ways):

I was a little chubby boy trundling a hoop in Chauncy Place and spouting poetry from Scott and Campbell at the Latin School. But Time, the little gray man, has taken out of his vest pocket a great awkward house (in a corner of which I sit and write of him), some acres of land, several full grown and several very young persons, and seated them close beside me; then he has taken that chubbiness and that hoop quite away (to be sure he has left the declamation and the poetry) and here left a long lean person threatening soon to be a little gray man like himself.

The hoop is real, a child’s toy. The hoop is also a figure for the wistful fusion of past and present, infancy and old age, since that is clearly where Waldo felt himself to be heading. There is Chauncy Place, at the corner of Summer Street, and there is Bush, on the Cambridge Turnpike—the essential geography of his life. Time has compensated Waldo for what he has lost with land, a house, children. It has transformed him, too, into a lanky middle-aged man who himself dabbled in eternity, made it his stock-in-trade: a Chronos on the village green.

But what was eternal? On his sixty-ninth birthday, engaged in some errands in Boston, Waldo found himself wandering by Summer Street. He was near the spot where he had spent his childhood, he later wrote in his journal, yet he could identify no familiar landmarks. In the “granite blocks” of the warehouses and stores he saw not a single hint of his “nearness to my native corner.” Nathaniel Goddard’s pasture was gone, he noted. So was the long fence that always ran along one side of it, painted the same shade of green that the owner, a shipping magnate, favored for his vessels.

In our childish moods, we expect what we remember to be there always. Waldo, pushing seventy, looked in vain for the yellow house. Instead there was Hovey’s department store, and a jeweler’s on the corner, and the twin awnings of the Mercantile Library across the street. Now these things, these plump specimens of reality and entrepreneurial zeal, seemed eternal.

The irony is that almost all of it would be gone just a few months later. The Great Boston Fire of 1872, which started on November 9, had its origins in the basement of a hoop-skirt factory on Summer Street. It devastated sixty-five acres of the city, including Waldo’s old neighborhood. In the stereoscopic images taken from the roof of Hovey’s—which happened to sit roughly on the spot where the yellow house had been—the ruins look apocalyptic, as if the structures had been not only scorched but taken apart brick by brick.

And what of Waldo’s other habitat? Concord had already reinvented itself more than once before he lived there. Prior to 1825, the village center had been a noisy, mosquito-infested hub of light industry, stinking from the tanneries on the Mill Dam. But that year, the town fathers decided to relocate the factories and replace them with the chaste white Federal structures that we now identify with the place. Even the elms, sycamores, and maples on the main drag were hastily parachuted in by the Ornamental Tree Society. Concord itself, then, was to some extent a simulacrum. It was an imitation New England village erected by a New England village.

This self-conscious feedback loop only intensified once Concord acquired its reputation as the American Athens. I have mentioned the swelling tide of Transcendental pilgrims who thronged the town during Waldo’s day. They came to stroll its visionary pavements and ambush its celebrities, and nobody was more scathing about Concord’s role as a mystical theme park than Louisa May Alcott. In a satirical piece published in 1869, she advised visitors on the best souvenirs (“orphic acorns by the peck”) and the most suitable lodgings, which were fitted out with “Alcott’s rustic furniture, the beds made of Thoreau’s pine boughs, and the sacred fires fed from the Emersonian woodpile.”

But she, too, was a creature of Concord and a contributor to its mythology. She knew that the place was “one of the dullest little towns in Massachusetts” and something amazing. Its qualities as a tourist trap couldn’t eclipse the slight, sublime, pollen-dusted, sometimes silly-making magic in the air. As Waldo once put it: “Things are, and are not, at the same time.”

It’s another of those statements that readers will never stop chewing over. It might be Waldo leaving himself an escape hatch, dodging any responsibility for the one million contradictions he had uttered in the course of a long career. It might be a nod to the idealists, whose undermining of the material world so disturbed him during his youth. It might be a statement about immortality—a way of keeping his vanished loved ones close to him, putting the living and the dead on an equal footing. It might be all or none of these.

Yet Concord, the alpha and omega of Waldo’s world, still endures. I was there on a June afternoon not so long ago, as I will certainly be there again. It was hot, bright, beautiful, and somehow oversaturated with itself. On the main street, young girls carried melting ice-cream cones in their hands, wearing skimpy outfits that probably would have made Waldo turn in his grave. And there, at 28 Cambridge Turnpike, itself a boring blacktop with a fresh yellow double-line painted down the middle, was Waldo’s house. It was close to the road, like something in the suburbs. This seemed a token of modesty—a representative man lived in a representative house. The sign told you it was his, announced the hours of operation and phone number and some extra material that had been redacted with strips of black tape, which I itched to tear off.

I did not. I toured the house and was moved by every single object—even the stuff in the study, which I understood to be a duplicate, a simulacrum at the heart of a bigger simulacrum. Here were Waldo’s hats, his walking stick, his engravings on the wall. Here was Little Waldo’s leather pull toy—a heartbreaking memento that his father had failed to consign to the flames in 1872. Here was the rocking horse Waldo had shipped from Liverpool in 1848, with its mild, fixed, forgiving expression. Here was the physical evidence of his time on earth. But I wondered whether it was also incidental. Did everything here point to some spiritual fact, which required neither a modern HVAC system nor the efforts of devoted curatorial staff? Waldo might be here and not here.

That left the cemetery. There it was also hot. In the Sleepy Hollow parking lot, which looked big enough to accommodate an IKEA, the heat bounced off the asphalt. The grass and trees and shrubbery were green, extraordinarily so, as if they had just been dipped in boiling water, except in the deep shade, where they looked colorless, dull, like ghosts of themselves. Some of the monuments resembled enormous chess pieces. Others were low and rectangular and blunt about who lay beneath then: MOTHER or FATHER and nothing more.

You went up the hill to see the community’s favorite sons and daughters. There was already a springy layer of dead pine needles on the path, which cushioned your feet and made uphill progress mostly silent. Waldo himself had consecrated Sleepy Hollow when it opened in 1855. He praised the undulating layout of the cemetery, the woods and the water, the way each family chose its own clump of trees. “We lay the corpse in these leafy colonnades,” he said, probably wondering where his own would come to rest.

Here, at the top of the ridge, was the entire cast of characters: Thoreau, Hawthorne, a small constellation of Alcotts. They had not always gotten along while they were alive. Their relations were prickly, erratic, full of disappointments—the price, perhaps, of truly Transcendental affections. Yet their adjacency up here, their nearness, was terribly moving.

Further down the path was the large Emerson family plot, marked off by rusty chains and stone bollards. I studied the gravestones—the low gray markers covered with words, lots of them, as if the living were under strict orders to explain the dead. They told what had happened; they were narrative objects of a kind, weathering away at the top of the hill. Waldo’s was different. It was a jagged hunk of stone, which looked to have been deposited by some Neolithic glacier or dropped from outer space. It was a boulder, that is, scarcely domesticated by the greenish bronze plaque affixed to its side. It was bigger, odder, more outlandish. Yet there was nothing egotistical about that massive piece of rose quartz, which was sturdier than marble and whose thinner edges might allow a hint of light to pass through.

So this is where it ended, I told myself. There were bald patches on the ground, where the flow of visitors had worn away the grass. In the dappled shade, I could hear the distant sound of car doors slamming and something like rushing water. Sometimes you are inhabited by things that you cannot explain. I had been thinking about Waldo for so long that his life now seemed to overlap my own, and I found myself stubbornly resisting the idea of an ending. Nothing is dead, he had written. I thought of the fire that had burned in his study every single day of his adult life, whose final heap of ashes had been reverently shoveled into his grave. I thought of the fire that had swallowed up the scene of his childhood—the apocalyptic aftermath, the scattered bricks and blackened timbers. I thought of my own father, too, who was alive when I wrote the first sentences of this book and who is gone as I write the last ones. If you could somehow run the footage of the Great Boston Fire in reverse, could you make the place whole again? If I read this book backward, will my father be there to greet me on the first page? These are fantasies, I know. Dreams of circularity, just like Waldo had, where beginning and end touch like two points on a hoop. But what of my own nearness to those who are supposedly vanished, consumed bit by bit by the conflagration of their own living? I don’t know what to make of it. I walk back down to the bottom of the hill. There, the oldest slabs—the sepulchers of the fathers—are just barely visible above the grass, and the black cars and silvery SUVs are idling in the sunshine, and I remind myself of the lesson I should have figured out in the first place, which is that nothing here is ever gone.

From Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Copyright ©2024 by James Marcus. Published by Princeton University Press, 2024. Reprinted by permission of the author and Princeton University Press.