Cover of a brochure outlining the U.S. government’s Homestead and Desert Land Laws, issued by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company. University of Arizona’s University Analytics and Institutional Research history of agriculture and rural life digital archive.

In the lead-up to Arizona’s recognition as a state, which would not happen till 1912, the territory’s political leaders knew that the U.S.’s politics of race meant that they needed to establish a firm white majority to win statehood. Simply removing nonwhite residents would not suffice; they also had to recruit white settlers to colonize Arizona.

Early on, territorial administrators tried to recruit more farmer-settlers from the East Coast by suggesting that the desert was an exciting place full of potential riches. From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, boosterist pamphlets published by institutions like the Chambers of Commerce for Tucson, Phoenix, and Maricopa County; Southern Pacific Railroad; and city and county immigration commissioners, as well as independent “immigration solicitors,” all emphasized the opportunities available to farmers from the East who were the desired settlers for state-builders in the Arizona Territory.

The companies and institutions publishing these recruitment materials were keen to see Arizona populated by settlers from the east because, it was understood, they were white. In his book on Arizona settlement, one self-proclaimed “pioneer,” John H. Cady, disparaged the Spanish colonizers’ assertion of civilizational superiority that East Coast settlers claimed, despite the fact that “the Spaniards possessed fully as white a complexion as the average pioneer from the eastern states.” Cady’s comments point to a broader debate about racial designation in the Arizona borderlands, where Spanish Americans engaged in a kind of counteroffensive against those who described the region as racially “unfit” for statehood by asserting their claims to whiteness. Boundaries around who did or didn’t count as white have long been politically charged in the United States, but as Katherine Benton-Cohen bluntly puts it, “Ultimately, agricultural promotion was for whites only.”

This dichotomy between white settlers and nonwhites was interwoven in the Arizona boosters’ definition of a new kind of agrarian idealism in the desert, exemplified in arid empire’s unique mastery of the “gospel of irrigation.” Of course, Indigenous residents of North America had been practicing irrigation for centuries, and some groups in Arizona like the Pima and the Maricopa were already major commercial agricultural producers by the mid-1800s.

Unsurprisingly, the colonial boosterist publications tended to be silent on this. Meanwhile, the grand scope of irrigation projects undertaken in colonizing Arizona destroyed Indigenous communities’ sustainable patterns of water use and farming in the desert not just by expropriating the water but also by damaging the broader ecological systems they depended on for their livelihoods. This was neither acknowledged nor framed as a problem in the settler stories about irrigation. If anything, controlling the water was explicitly acknowledged to be about establishing absolute control of the land. An 1885 publication on the Salt River Valley makes this explicit: “In desert countries like the valleys of Arizona, water is king, and he who owns or controls it becomes dictator, and rules even the cultivator of the soil.”

If great wealth reaped from Arizona’s soil was a key promise of the recruitment brochures in the 1800s and early 1900s, this quote lays bare the fact that control of the land also required control of the water. Out west, the would-be settler could be more than an entrepreneur—he could be a dictator. The idea of settlers as dictators runs counter to the democratic idealism that glosses dominant American conceptions of Western expansion with the brave spirit of agricultural pioneers and homesteaders. Yet this retrospective nationalist storyline is divorced from the realities of colonization. Indeed, the boosterist materials suggest that dictatorial control might have been useful in selling settlers on a move to the desert Southwest, in part because of the region’s association with frontier lawlessness.

Local boosters exerted a great deal of energy—and exaggerated rhetoric—to shake off the “Wild West” stigma and replace it with a different image of agricultural paradise. For example, one publication from the 1800s says of Central Arizona: “It is no longer the frontier—the sweeping wave of civilization has covered it. The cactus has been thrust back and the plain has been made a garden, threaded by great canals wherefrom the farmer draws for the irrigation of his fertile acres.” It then goes on to emphasize that the (perceived) threat of Indigenous attacks on white settlers has subsided: “The Arizona Indian of today is no longer savage. He is still picturesque, but is rapidly being merged into a most ordinary division of the body politic.”

Most, if not all, of the Arizona settler-recruitment publications were silent about whose land their audiences in the East would be settling. Instead, they celebrated the desert as a blank slate, trying to generate excitement among would-be Arizona residents and entice them to imagine all that they could build and grow on this drawing board in the sand. Once emptied and imagined as a space outside of politics, the desert-as-laboratory became a testing ground for the settlers’ ideas of modern science, Western ingenuity, and the creative injection of ideas from the Old World to make the New World thrive.

The “Old World” was not Europe but, in fact, the biblical one: boosterist brochures were filled with references to the Colorado River Basin as the American “Nile,” which it was said offered all the fertile land needed for prosperity and progress. To build a new arid empire in the United States, where better to look than the Middle East?

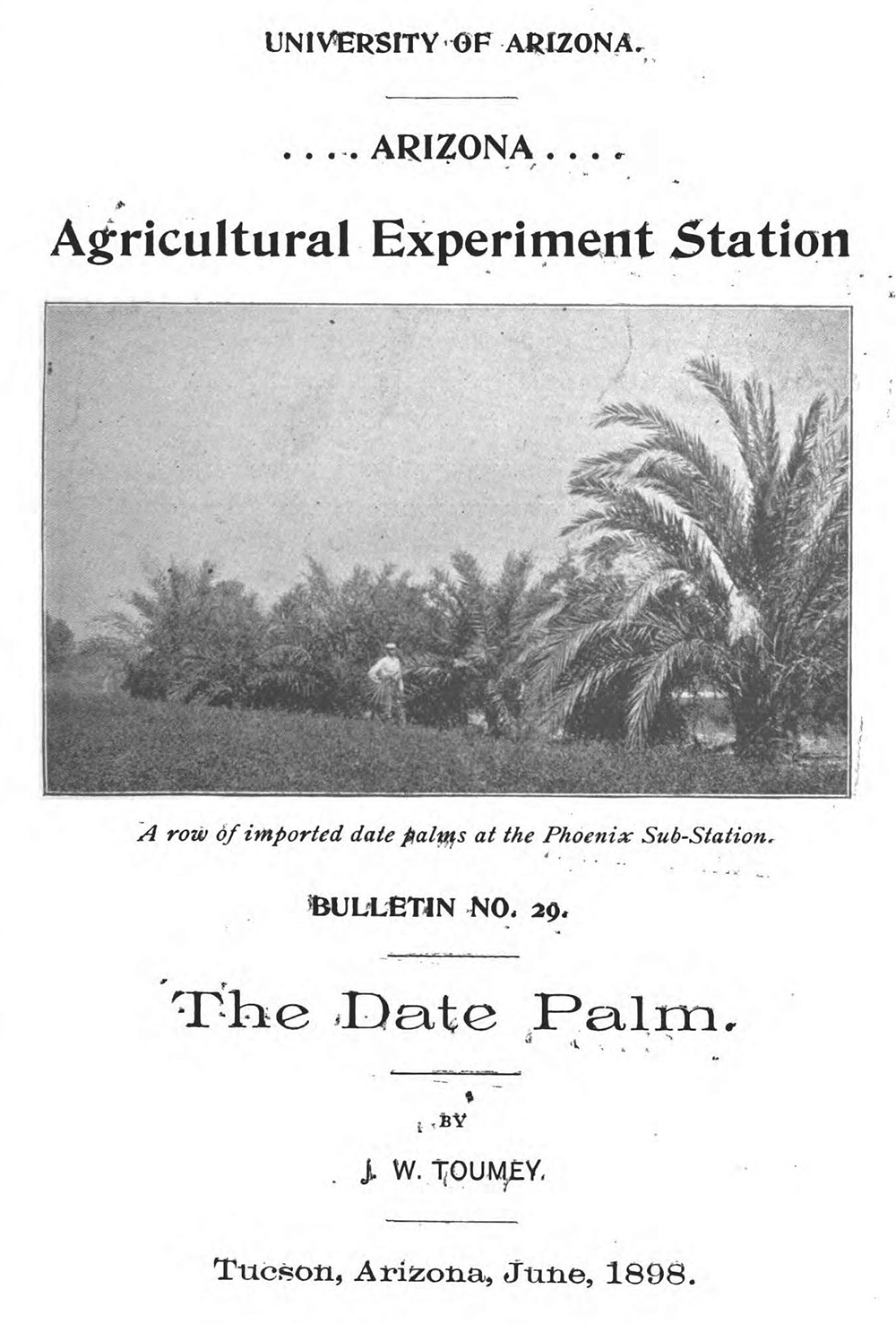

One staple of the Middle East’s own agricultural power in its arid regions was date cultivation, which quickly became an object of desire for U.S. agents of empire. The date was an exotic but much coveted fruit in America in the late 1800s. The first directors of the University of Arizona’s Agricultural Experiment Station (AES), which began operations in 1890, all believed that they could build a domestic date industry on the basis of its existing popularity.

These men—Frank A. Gulley, James W. Toumey, and Robert H. Forbes—became proponents of the university’s first experiments with date palms and worked with private and government agents to import diverse date varieties from around the Middle East through the 1890s and early 1900s. The first decades of AES’ work were largely focused on expanding Arizona farmers’ capacity for date cultivation.

The date was, in this period, an imported specialty fruit that was much in demand in the United States. Muscat, Oman, was, in the 1800s, the center of Arabian date exporting and specialized primarily in the fardh variety, which was hardy enough for long ocean journeys. Upon arrival in the U.S., the dates were not sold fresh but in huge congealed blocks that grocers would then portion off for consumers. Dates were not available year-round, arriving only on ships from the Gulf around Thanksgiving and Christmastime. Americans apparently loved the sweet, sticky treat, and it quickly became a beloved part of the American holiday season.

When records of date importing began in 1824, the U.S. imported 44,425 pounds of dates, and these figures increased dramatically over the rest of the century. By 1885 the country was importing more than 10 million pounds of dates annually, growing thereafter to as much as 20 million pounds annually between 1893 and 1903. By 1920 imports were up to 32 million pounds; by 1922 53 million pounds. Around the turn of the century, grocers were selling millions of pounds of dates during the holidays. With this booming business, the United States had become Oman’s most important foreign customer.

In 1899 New York newspapers even began an annual “date race” for the first shipping company to arrive from the Gulf with the year’s date supply: Would it be the boat from Muscat or Basra? Eager readers could track the progress of the boats as they sailed, and the winner was feted and awarded a handsome cash prize. The newspapers clearly understood that the hype helped sell papers—itself a testament to the public’s passion for dates.

Spanish missionaries had grown date palms from seed at missions in California and Arizona before those lands were acquired by the U.S. in 1848. After the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) was founded in 1862, there were some murmurs of interest in investigating the Spanish palm experiments further. But it wasn’t until 1882, when the American demand for dates was just beginning to take off, that the USDA finally sent an agent, W.G. Klee, to survey the Southwest and evaluate whether a domestic date industry in the region was viable. Klee’s report was positive, but several years passed before he was sent back for a more comprehensive study in 1887.

Klee’s reports, combined with the skyrocketing date imports to the U.S., led the USDA to start procuring date palms for testing in Arizona, California, and Texas. The USDA tried to get as many different date varieties as possible to test out. From 1890 until 1929, it would import around 20,000 palm offshoots from 149 different date varieties. The USDA had a Division of Pomology and Section of Seed and Plant Introduction, which included “agricultural explorers” (a real title) on staff. Part of the United States’ long-running project of agricultural state-making, these men traveled the world to collect plant varieties with the potential for kickstarting commercial farming in the United States.

By the time the USDA got involved in palm imports in the 1890s, farmers and scientists knew that date-palm seeds could not be trusted to produce palms that bear fruit true to their source. Trees grown from seed can produce radically different plants and fruit from their parent source and sometimes won’t even produce fruit at all. For this reason, the USDA had to import “suckers,” or palm offshoots, which grow at the base of a tree. Safely transporting the suckers from the Middle East to the United States was a major challenge because they had to be regularly watered and cared for throughout the months-long journey by boat and rail.

These efforts were championed in Arizona by Robert H. Forbes, who assumed the AES directorship in the late 1890s and held the position until 1915. Like his predecessors, Forbes discovered his inner date-palm enthusiast almost immediately. In fact, he took date industry optimism to another level: he would go on to dedicate the next several decades of his career to some aspect of the industry, first in Arizona and later in northern Africa. Forbes was originally from Illinois and trained in chemistry and agriculture. Not long after he moved to Arizona, he married a local woman from a prominent settler family and quickly became enchanted with the desert.

By the time Forbes arrived in Arizona in the 1894, American popular culture was densely populated with romantic Biblical and Orientalist narratives linking the deserts of the U.S. and the Middle East. Forbes was fascinated by these connections and soon became an evangelist for desert-to-desert learning.

He believed the best way to establish control of the new arid lands of the American West was to borrow heavily from Old World desert countries. Forbes looked closely at date farming in the Middle East when he took up the AES’ fledgling efforts to start its own date industry for the United States. He imagined Arizona’s Experiment Station becoming a sort of local repository for this knowledge and a conduit for local farmers, writing in 1900:

But in the date-growing countries of the Old World the Arabs, and other races, have developed the date until in excellence and variety it corresponds with other cultivated fruits. Knowing that the conditions, especially of climate, enable the tree to produce in Southern Arizona, it is evidently necessary to avail ourselves of the centuries of Old World experience, bring the best varieties from the Sahara, Egypt, and Arabia, and establish them here. This is what the Arizona Experiment Station with the help of the Department of Agriculture is now doing.

Forbes’ vision basically involved redeploying agricultural insights of “Old World” communities to the U.S. Southwest, but in a way that would position the AES as innovative, entrepreneurial, and of course an ally to the settler farmers they were tasked with supporting. “Colonization,” Frieda Knobloch reminds us, “is an agricultural act.”

One of the most significant contributions that AES directors Gulley, Toumey, and Forbes all made to Arizona agriculture was to institutionalize the idea that the desert Southwest was an “American Middle East.” The idea predated them, but their work at the Agricultural Experiment Station both reinforced the metaphor and went beyond rhetoric. By actually importing the raw materials—palm offshoots and other crops—and seeing them to literal fruition, they gave life to the trope in the real world.

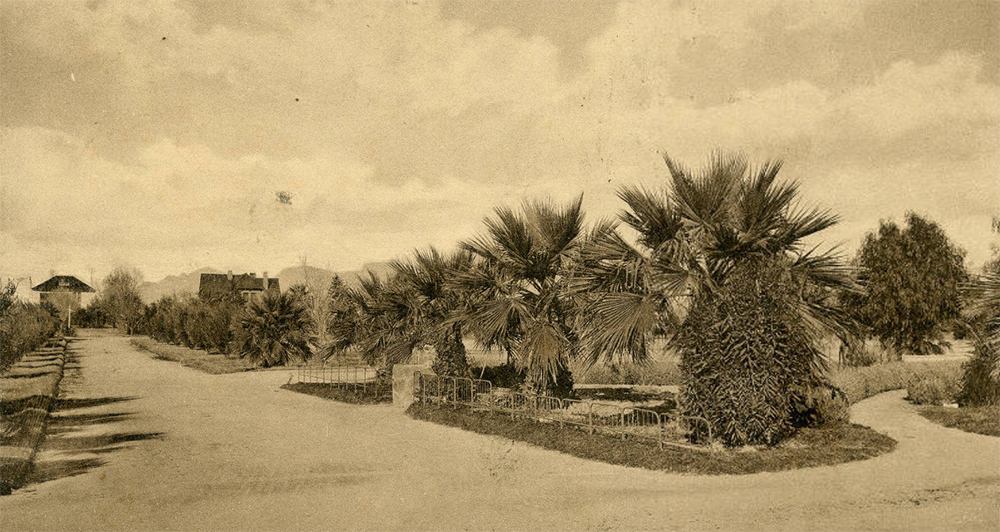

Early advocates of date cultivation in the Southwest found allies in the press, who helped to broadcast the spectacle far and wide. As the trees started to grow, the seductive image of prolific palms quickly became a prominent theme in the Arizona boosters’ recruitment materials. The media also reported extensively on the AES work with date palms and the promise of domesticating this industry. Equally seductive was the image of transforming a desert “wasteland” into a paradise, a trope which the news reports frequently trotted out. In one Scientific American article from 1899, for example, the author reports: “It is now proposed by our Commissioner of Agriculture at Washington to make the date a staple American product also. The center of this new enterprise is to be the now useless desert regions of southern California and Arizona. Seed has been procured in Egypt and successfully planted, and more is coming.”

When, in 1924, the Date Growers’ Institute was established and held its first meeting in Coachella, the date palm was a veritable icon of the settlers’ ingenious civilization of the American Southwest through “Old World” agricultural imports. The chairman’s opening statement highlighted the impressive speed by which the region went from having just a few “purely experimental plantings” of dates to becoming home to thousands of varieties: “The transposition of date palms from the Old World to the New and the successful establishment on a new and modern basis here in our own Southwest of an industry as old as civilization itself, marks what is perhaps the most wonderful of all great achievements in the realm of horticulture.”

Despite the key role of the AES and other Arizona-based advocates, U.S. date production is now concentrated in California, having surpassed Arizona’s production by around 1915. The date industry was set for a steady decline in Arizona after 1950 due to weather challenges, increased production costs, foreign competition, widespread availability of sugar following World War II, and a boom of urban development in the state. But when the AES was actively promoting its date palm experiments in the late 1800s and early 1900s, this work was declared an “unqualified success.” The palms proliferated around the state, and photographs of the opulent fruit-bearing trees figured prominently in advertisements for the university and the region more broadly.

Some obvious losers were ignored in the nationalist declarations of victory: the date producers in Oman and other countries in the Middle East and North Africa. For them, Arizona-based efforts to establish a U.S. date industry marked a process of slow but accelerating decline, and by the late 1920s the Gulf region’s most lucrative export market was undercut by the American crops.

Excerpt from Arid Empire: The Entangled Fates of Arizona and Arabia by Natalie Koch, published by Verso Books. Copyright © 2023 by Natalie Koch.