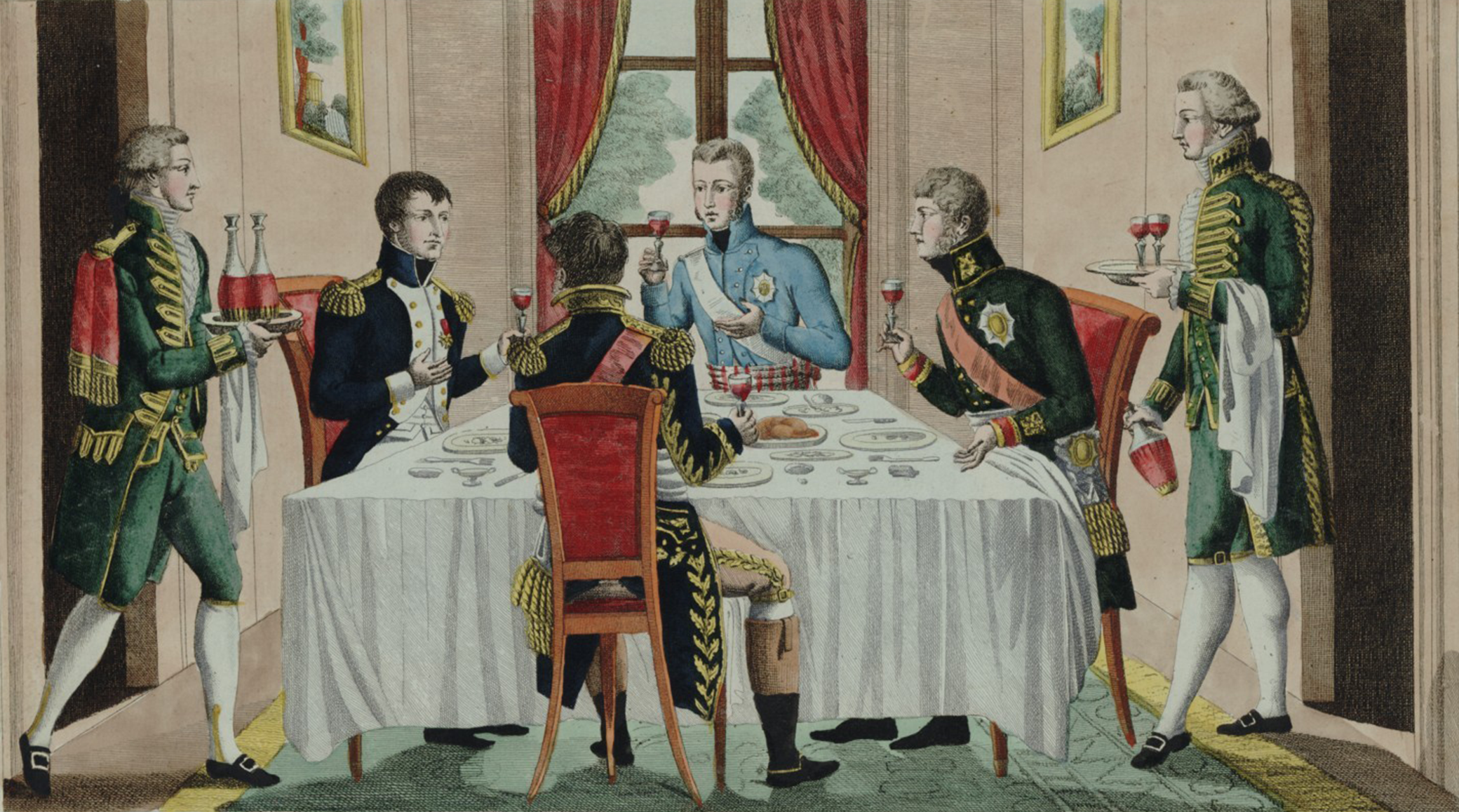

Dinner with Napoleon, Alexandre I, and Frederick III, 1807. National Library of France, Prints and Photographs Department.

Eugène Briffault (1799–1854) was a journalist and editor who chronicled Parisian dining during the time of Balzac. This is an excerpt from the first complete English translation of his Paris à Table: 1846.

In France, the principal meal of the day has, historically, been called “dinner.” Having little curiosity about gastronomic archaeology, we will not be searching, in the archives of the past, for the precise times for dinner. What is most important for us to know are its true manners and customs, and we will ask of memory only what is necessary to clarify the present; and that is just as well, since erudition at the table would be no more than inappropriate, annoying, and in bad taste.

In 1667, in Paris, you dined around noon; this time is confirmed by the line in Boileau’s third satire:

“I rushed over, at the end of Mass, just as noon sounded.”

Not only do we find, in this citation, the precise hour for dinner, but it also tells us that this meal, among civilized nations, has always been placed near the day’s most important event. During the iron ages, the centuries of combat, you dined when you could, sometimes after the battle, sometimes before. Charlemagne wanted feats to be performed before any nourishment was taken; Henri IV, on the other hand, wanted his soldiers to have a bit of beef in their stomachs before facing the enemy. When leisure became the ultimate object of French society, dinner, taken by warriors during the first hours of daylight, drew closer to the middle of the day, settling in between eleven and twelve. In the seventeenth century, the daily devotions, whose duties and requirements marched in step with the splendors and rigorous etiquette of the court, fixed the time for dinner, placing it at the close of the divine office, “at the end of Mass.”

Later, dinner seemed to interfere with the dissipated life publicly avowed by the entire court; the previous century’s timing seemed impractical when bedtime was at daybreak; it became far too troublesome to sit down at the table at noon; for a long time, then, dinner was only an inclination; it was endured, not accepted. Under Louis XIV, dinner was after Mass; under Louis XV, supper came after the theater; among the nobility and for the wealthy class, supper was thus created out of a loathing for dinner.

In the following regime, habitual ways calmed down a bit: dinner was around two o’clock; supper, without shedding much of its brilliance, was maintained. At the court of Louis XVI, a leisurely protocol was observed and without any fuss, daily life followed a plan, and hours were fixed for eating. A few of the chosen—appearing at their head the Lauzuns, the Richelieus, the Comte d’Artois, and the Queen’s intimates—preserved for themselves the privileges of another time; but despite these brilliant exceptions, court and city took pride in regularity: dinner was generally between noon and three.

It would be quite difficult to say at what time the era known as the Revolution dined. During that upheaval, the country’s entire being was drawn toward political meetings and public places; the private person’s life had disappeared completely, leaving visible only the life of the citizen. Eating was done quite hastily, and, if some excesses persisted through these times agitated by such violent and terrible passions, they left no trace. Most of the men on whom the destiny of the country seemed to depend are remembered only as being sober and showing little concern for the pleasures of the table. Two years ago, in rue du Dauphin at the corner of rue de Rivoli, a humble eating house—designated as the place where the most ardent orators then gathered at the dinner hour—could still be seen; their words are retained in our memory, but what constituted the meals to which they themselves were totally indifferent, is no longer known.

The Directory restored dinner to favor; it even brought opulence, luxury, wealth, and finery to a point that recalled the pomp and the taste of the most brilliant chronicles of the table. In the wake of passion, vice followed; society was as debilitated and corrupt as it appeared to be rough and austere; for the excess of heroism, the excess of egoism was everywhere substituted; those growing wealthy with the most scandalous speed imitated or rather aped, through the pride and the foolishness of their extravagance, those financiers of a former time whose prodigality had so amused the nobility they had intended to humble. There were also, among the bourgeoisie, sudden fortunes recalling those of rue Quincampoix; to satisfy their vanity, they spent wildly money so easily earned. Politics ruled the nation’s affairs only by means of seductions, the choice of which, on the part of both sides, appeared to be far from scrupulous; pleasure was the means most often put to use. There was, throughout all of this world, a feverish disorder, an insane dissipation, and a passion for sensuality that generated only fierce or bizarre pleasures, whose extravagant prodigality did nothing for elegance or for taste. Among those who shone the brightest during this time where lunacy and debauchery held such a large place in the business and amusements of the day, only a few knew how to evade these ridiculous impulses. This delirium of the Directory was a necessary crisis between Republican rigidity and the Empire’s civilization, the first light of which was illuminated by the Consulate.

There is an unavoidable name, and one that the chronicle of the first thirty years of this century always encounters along the way: it is the name of M. de Talleyrand. There is not a single quality envied by the world that has not been attributed to him: he was deemed the first among political men and the last of the great lords; the spirit of France, in its entirety, was granted to him; his high office and his fortune always placed him near a throne he often dominated with his skill; he drew the good will of sovereigns, the favors of women, the adulation of the ambitious, the hatred of honest people, and the sarcasm of the crowd. As if all that were not enough to make a man famous, gastronomy took hold of him and ruthlessly placed him in the pantheon of the culinary arts. We do not intend to protest against this part of his fame; the facts have often taken care to correct whatever was askew and misguided in the praise bestowed on Talleyrand’s epicurean ways. For him, refined hospitality and fine food were only a means to serve his purposes and in no way his inclinations.

The first and most precious of Talleyrand’s qualities was his tact; it was for him swift and sound, exquisite and sure, almost infallible; his wit was endowed with all that was lacking in his heart. He came from the Old Regime; he had tiptoed through the Revolution, and the Directory’s bad taste horrified him: but he joined in on the Luxembourg voluptuousness without a single complaint, disguising his disgust, taking care to reduce those enormities to reasonable and just proportions. Talleyrand made of his residence the model for a taste, a luxury, and a courtesy, the like of which now seems lost. The merits of his receptions have been attributed to his chief steward. This servant, who had started off with the Princess de Lamballe, came, it is true, from the house of de Condé; but dinner at the Foreign Affairs residence was not the only thing that drew society’s elite to the minister’s home; the conduct, manners, and flair found within this dwelling had a charm of irresistible attraction. With Talleyrand diplomacy was practiced everywhere, in the sitting room and at the office; his head chef was charged with the task of selecting all the cooks for the great houses abroad; this was to obtain intelligence directly from the heart of the place.

Dinner, we can all readily agree, was nevertheless a serious affair for Talleyrand; every morning he settled on the menu himself with his chef. His table normally had ten to twelve settings; his service consisted of two soups, two opening dishes—including one of fish—four additional starters, two roasts, four sweets, and the dessert. We go into detail here because this arrangement became the standard rule for all the Consulate’s great tables. The major contractors, the financiers of the time, persisted in their heavy excess; several feasts at Raincy, the home of M. Ouvrard, however, deserved notice and succeeded in being absolved.

Seated at Talleyrand’s table were not only all of those celebrated in France, but all who had made some noise in Europe and in the political world; one of the principal attractions of these meals, especially considering the private nature of some of the guests, was the conversation; the art with which these discussions abstained from any openness or spontaneity was admirable; this was a fencing match where swords crossed with surprising dexterity.

The Empire found the guidelines, rules, recommendations, and examples all in place; it restored to the dinner its order and a regular and proper beauty that took nothing away from its independence and its delights, and gave to its pleasures a character that, at the same time, satisfied reason and taste. But the table at the Tuileries never had any importance; Napoleon pretended to pay no attention to details that were beneath him: he ate quickly and selected the simplest of foods. And despite all the pains taken by gastronomic investigations to burden him with certain odd traits, regardless of the slanders that tried to reveal the Emperor to be as intemperate in private as he was sober in public, all that is left of these tales are his regular habits that are full of modesty, reserve, and restraint.

From Paris à Table: 1846 by Eugène Briffault and translated and edited by J. Weintraub. Copyright © 2018 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.