The Wyndham Sisters: Lady Elcho, Mrs. Adeane, and Mrs. Tennant, by John Singer Sargent, 1899. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1927.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

“The gilded bondage of the country house becomes onerous as one grows older,” mused Henry James in an 1886 letter to Charles Eliot Norton. “The waste of time in vain sitting and strolling about is a gruesome thought in the face of what one still wants to do with one’s remnant of existence.”

A longtime expat by his early forties, James had been welcomed into a rarefied English circle whose social life revolved around lavish gatherings at country estates. It was a milieu he lauded—when younger and less jaded—as “the most perfect” of English inventions, “a compendious illustration of their social genius and manners.” The grand houses that appear throughout his fiction are renderings, often barely altered, of real places he had stayed. Hardwick House in Oxfordshire, a distant relative’s redbrick Tudor mansion, became Gardencourt, described with such reverence in the opening scene of The Portrait of a Lady. For The Golden Bowl’s party at Matcham, attended by Amerigo and Charlotte before their first illicit tryst, James may have recalled visits to the Jacobean manor Stanway, the Gloucestershire home of renowned hostess Mary Charteris, wife of Hugo Charteris, Lord Elcho. And Foxwarren Park, a neo-Gothic pile in Surrey so ugly that being there caused him “anguish,” was reborn in The Spoils of Poynton as Waterbath, owned by people “from whose composition the principle of taste had been extravagantly omitted.” As such, it provides a suitable foil to the splendid Poynton, which was partly inspired by Clouds, the southwest Wiltshire home of Mary’s parents, Percy and Madeline Wyndham.

But the chance to acquire physical settings for his characters wasn’t the only attraction of those weekend parties in the shires, which James continued to frequent even as he complained about them. For that pioneer of psychologically intricate tales, the wealth of material to be gained simply by watching those around him was enough of a draw. Strolling across shaded lawns, relaxing in comfortable drawing rooms, and seated around crowded dinner tables, he witnessed dizzying sexual crosscurrents, shifting devotions and deceptions, and virtuoso social and political power broking. That scrupulous codes of etiquette veiled less than scrupulous behavior only heightened the fascination.

At summer’s end in 1887, Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year, James attended one such party at Clouds. The Wyndhams, then in their early fifties, were central figures in an ultra-privileged clique of aristocrats and politicians known as the Souls, among whom James counted many friends. Disdaining the shooting-and-hunting philistinism of the Victorian upper class, the Souls prized intelligence and aesthetic refinement and were keen patrons of the arts. By inviting professional writers and painters into their orbit, they created occasions of unprecedented social diversity. “Whereas in the courts and salons of Europe men of genius had always been sought after and lionized,” writes Angela Lambert in Unquiet Souls: The Indian Summer of the British Aristocracy, “in England the social gap between the fashionable painter and his aristocratic subject was, in the nineteenth century at least, thought too wide for society to risk. But the Souls bridged it.” To the scandalized Duchess in The Awkward Age, a certain country house known for hosting lots of guests contained “extraordinary mixtures.”

The Clouds estate, all 4,207 acres of it, was bought by Percy Wyndham in 1876, and he and Madeline set about demolishing the existing late eighteenth-century house and building their own illustrious family seat. They commissioned architect Philip Webb, a leader of the Arts and Crafts movement and a founding partner in the William Morris firm, to design a house worthy of passing down the generations. Caroline Dakers, author of Clouds: The Biography of a Country House, explains that Webb was a “wholly radical choice,” given his uncompromising creative vision and unorthodox ideas. The collaboration between Webb and the Wyndhams was nevertheless fruitful, though it would be nine years before the vast hilltop spread and its arrangement of formal gardens were completed and ready for admiring guests. The planning and construction cost £80,000—the equivalent of approximately £8 million today.

A friend of the Wyndhams described Clouds as “a glorious Kate Greenaway affair, all blue and white inside, and all red and green outside.” Incorporating various architectural styles, including Gothic Revival and monumental classicism, the house was built from locally quarried green sandstone, with a redbrick upper floor. The light-filled interior, said to smell of cedarwood, beeswax, and magnolia soap, was modern in its simplicity, with mostly white walls, pale oak paneling, carved stone pillars, and William Morris carpets. It was the perfect backdrop to the couple’s collection of art from throughout the centuries and furniture by Hepplewhite and Chippendale, as well as contemporary pieces such as a pair of oriental black-and-gold lacquer chests, bought at a D.G. Rossetti studio sale, and a huge Edward Burne-Jones illustration of the Annunciation—Christ surrounded by archangels with gilded halos—which took pride of place on the main staircase wall.

Practicality was not sacrificed for beauty, with carefully concealed rooms designated for the endless and myriad domestic work and ample living space provided for the thirty-odd indoor staff. In the words of Webb’s biographer, fellow Arts and Crafts architect William Lethaby:

The house itself marks the end of an epoch. It appears to have been imagined by its gifted hostess as a palace of weekending for our politicians. It was planned to have the residential and reception part almost detached from the service block. The former is square and high, and the latter is low, rambling away to the east, lighted mostly from its own court and half-veiled externally by the trees. It was the affectation of the time that work was done by magic; it was vulgar to recognize its existence or even to see anyone doing it.

On the first weekend of September 1887, partaking of the magical hospitality at that palace of weekending were Mary Charteris, her younger brother George, a solo Georgiana Burne-Jones (Edward rarely accepted country house invitations but liked his wife to go in his stead), and many other friends and relatives. Poet and Arabist Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who was a cousin of Percy’s, was accompanied by his wife, Lady Anne (Byron’s multilingual granddaughter who, like her husband, was a horse breeder and traveler), and their shy fourteen-year-old daughter, Judith. Blunt was close to the whole Wyndham family and adored Clouds, which he was encouraged to treat as a second home. That weekend, in between playing games and shooting partridge on the Wiltshire Downs, he and George read their poetry to one another. In his diary, Blunt praised George’s new work: “several excellent sonnets” and two longer pieces “of very superior merit.”

In the spring, George had accepted a job as private secretary to Arthur Balfour, the Conservative chief secretary for Ireland, future prime minister, and leader of the Souls. But George, at twenty-four, was torn between a career in politics like his father—Percy was a Conservative MP for many years—and devoting himself to his art. It’s a dilemma he shared, Caroline Dakers notes, with Nick Dormer in The Tragic Muse, who abandons parliament for his painting studio and so loses the hand of a rich widow. George, whose hyperbolic appellation was “the handsomest man in England,” had just married his own rich widow: Sibell, Lady Grosvenor. She was just twenty-eight when her first husband died, and she became the inspiration for Lady Vandeleur—“the most beautiful widow in England”—in James’ 1885 short story “The Path of Duty.”

Blunt disapproved of George marrying a mother of three who was eight years his senior, even if she was lovely and hugely wealthy. Given the assembled company, he also had reason to contemplate his own romantic choices, past and present. Many years earlier, he and Madeline had enjoyed a passionate affair, and now his sights were set on Mary. Another guest, Madeline’s niece Sibyl, had once been in the running to be Mrs. Blunt. But at forty-two, she was “marked deeply with the crow’s foot,” he noticed, “brought on more by trouble than time.” Recently divorced from the Marquess of Queensberry on the grounds of his adultery, Sibyl had come to Clouds with two of her children: thirteen-year-old Lady Edith Douglas and sixteen-year-old Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. It was thought that sixteen-year-old Pamela, the Wyndhams’ lively youngest daughter, might be a match for one of Sibyl’s four sons, and she and Bosie sat together at dinner, noisily playing a rhyming game. Just a few years later, he began his fateful romance with Oscar Wilde and became part of gay history.

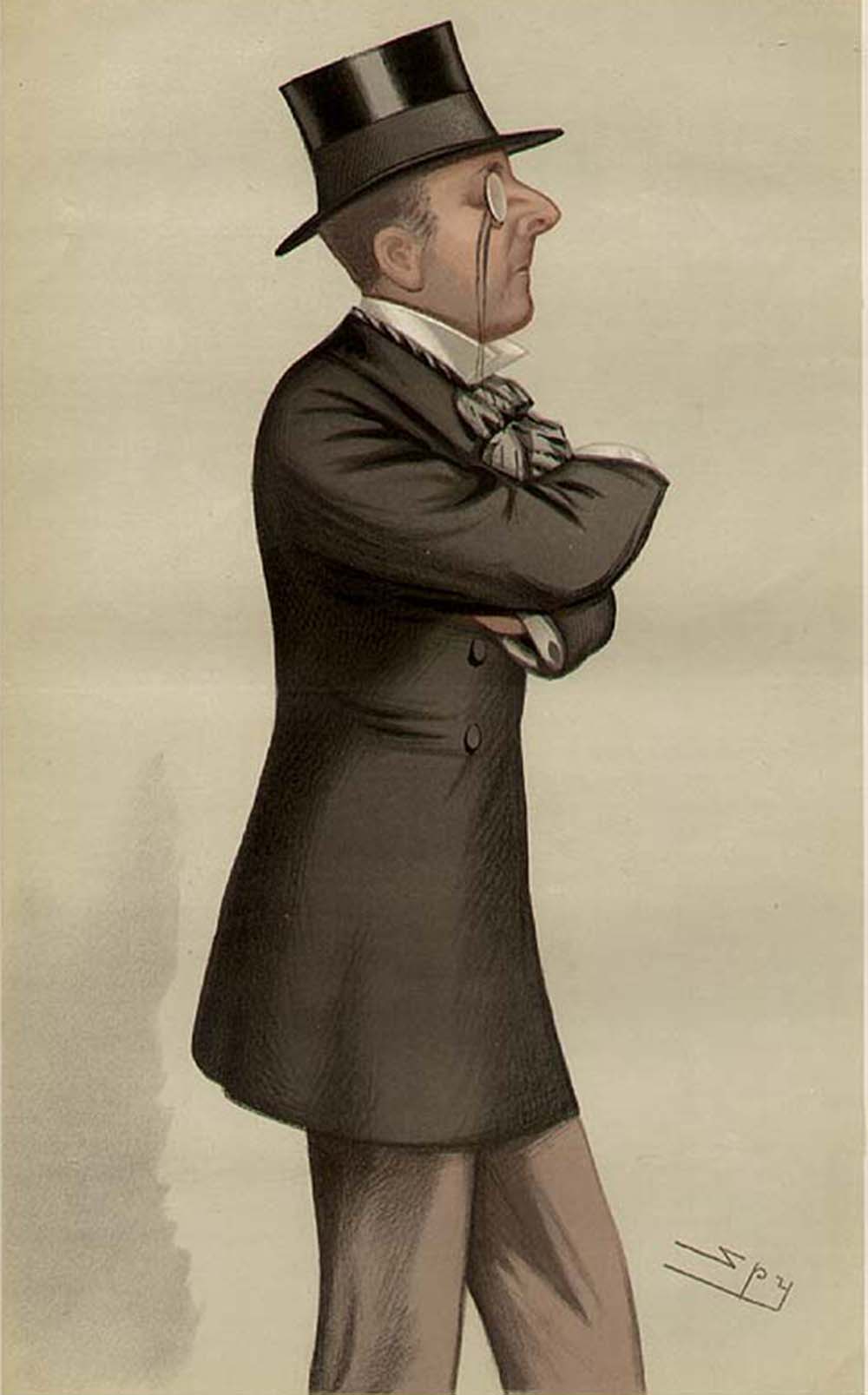

On Saturday, James arrived with Balfour. Despite his enormous inherited wealth and many admirers, at thirty-nine Balfour remained, like James, resolutely single. The two committed bachelors had been marked by death in a similar way as young men. Minny Temple, James’ adventurous cousin and the bright light of his youth, died of tuberculosis when she was twenty-four and he was twenty-six. The animating spirit of his doomed American girls abroad—Isabel Archer, Milly Theale, Daisy Miller—is Temple. When Balfour was twenty-two, his cousin May Lyttelton, a beautiful dark-haired twenty-five-year-old he had wanted to marry, died suddenly of typhoid fever. In secret, Balfour had his mother’s emerald ring buried with her as a symbol of his intentions. A wall of invulnerability then went up, never to be breached. James’ analysis of the politician in a letter to his brother, William, was unsparing but not untypical of people’s impressions:

In spite of his extremely pleasant, lazy and apparently sincere manner he is the type of latent aristocratic insolence and scorn, of the extremely refined and intellectual sort. He is extremely witty, and a master of persiflage and badinage and, at the same time is of the cold, ascetic and unfleshly type…indeed a prodigy of amiable heartlessness. It all comes back to race—high Scotch Tory ancestry, lands and dominions.

No one knew for sure if Balfour really was “ascetic and unfleshly”—it was a much debated question—except perhaps Mary, who was his closest confidante. As a teenage debutante she had hoped he would propose, and earlier in 1887 they had embarked upon an affair of sorts, even though she was pregnant with her third child. At Clouds they took the opportunity to pair off on long walks and indulge what Blunt called Mary’s tendresse. The poet was jealous. True, she was eight months pregnant, half his age, and her parents were his ex-lover and his cousin. But for Blunt, these details little detracted from, and maybe even enhanced, the allure of the twenty-five-year-old brunette with heavy-lidded eyes who, he confided to his diary, was “the cleverest best & most beautiful woman in the world.” Balfour, he lamented, “is in love with Mary…to whom he makes himself of course charming, but, possibly for the same reason, I do not like him much.”

Blunt’s antipathy for Balfour that weekend was not just personal but political. In the world beyond the hermetic luxury of Clouds, the battle over Ireland’s future was reaching a flash point. While Balfour’s job was to quash Irish nationalism, drawing-room revolutionary Blunt was a campaigner for Home Rule, the transfer of power from Westminster to Dublin. James had little patience for politics in his own life, feeling that the “oceans of talk that are required…make one long at moments for some fine dumb despot.” Yet from a detached anthropological perspective, he found the Irish question of great interest and had considered visiting Ireland simply “to see a country in a state of revolution.”

On Sunday afternoon, the Irish National League, a political party lobbying for tenant farmers’ improved rights as well as for Home Rule, was due to hold a meeting in contravention of Balfour’s recently introduced Crimes Act. A draconian piece of legislation in a series of coercive measures aimed at imposing order in Ireland during the Land War—a decades-long period of agrarian unrest characterized by rent strikes, violent evictions, and boycotts—the act allowed political agitators within “proclaimed” districts or organizations to be imprisoned without a jury trial. In August the National League had been proclaimed—that is, prohibited from political activity—and their unlawful assembly was expected to signal a mighty clash between stalwart nationalists and police.

Balfour, who coined the saying “Nothing matters very much and few things matter at all,” had ordered his office not to bother him with telegrams at his favorite country retreat. At the same time as a grave conflict was anticipated, he played lawn-tennis doubles, partnering with Guy, the middle Wyndham sibling, against Blunt and George. It was absurd, wrote Blunt, “my being here playing tennis with the chief secretary on the very day and at the very hour of the Ballycoreen meeting, where he evidently expects bloodshed.” After the match, Balfour said casually to George, “I suppose it’s all over now.” As it turned out, and to everyone’s surprise, the meeting took place calmly and without incident.

That evening at dinner, Ireland continued to dominate the conversation, with Balfour admitting, contrary to official Tory policy, that Home Rule was inevitable, and that when it eventually came he wouldn’t be sorry. The following year Blunt, flouting the social custom that what happens at the country house stays at the country house, made controversial public declarations regarding Balfour’s true intentions toward Ireland, leading to coverage in the Times and discussions in the House of Commons. The Wyndhams were incensed at this violation of their guests’ privacy, and for some months James lived in fear of being asked to testify on what, exactly, had been said around the table. He wished only to offer fictionalized, not indiscreetly factual, accounts of Souls intrigues. Privately, he thought Blunt a “humorless madman.” The dislike was mutual: Blunt found the novelist “distinctly heavy in conversation and for a man who writes so lightly and so well it is amazing how dull witted he is.”

For his part, Balfour had extended no clannish favoritism to the disloyal Blunt, who not long after the Clouds party was arrested when he got up to address the crowd at a proscribed anti-eviction meeting in a Galway field. “We are trying to put your cousin in jail,” Balfour wrote to Mary. “I have not heard whether we have succeeded: I hope so, for I am sure Blunt would be horribly disappointed at any other consummation.” There was no disappointment. As punishment for defying Balfour’s Crimes Act, Blunt spent eight weeks in a Dublin prison, doing hard labor.

Seven years later, he settled the score by at last seducing Mary. She had taken three of her four children, along with a governess and a maid, on a trip to Egypt, where the Blunts spent half the year. During a camping trip in the desert, the cousin whom Blunt had long desired became, as he put it, “my true Bedouin wife.” Mary returned to England pregnant yet handled the situation with aplomb. In keeping with aristocratic mores, her husband raised the child as his own, albeit with gritted teeth. “If it had been Arthur,” he supposedly told her, “I could have understood it…I shall forgive you, but I shall be nasty to you.” In fact, they had two more children together. As for Balfour, her bond with him remained unbroken. When one thinks of Mary “with her hold on her husband, her ‘friend,’ her children and her social life intact,” writes Claudia Renton in her riveting biography Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power, “it is very hard to resist giving her a silent, heartfelt cheer.”

In 1895, when Mary was pregnant with Blunt’s daughter, the Wilde trials were sending shock waves through society, particularly among the Souls. Not only was Wyndham kinsman Bosie Douglas the catalyst for the entire saga—which began with his father accused of libel for branding Wilde a “posing sodomite” and ended with the Irish playwright imprisoned for gross indecency—but Bosie himself may have avoided serious trouble only thanks to his fortunate connections. He discussed the situation with George, who in turn obtained reassurance from Balfour, by then prime minister, that no case would be brought against his cousin. James, meanwhile, was recalling the occasion of his meeting the sixteen-year-old Bosie for reasons other than the avid newspaper coverage of the scandal: the story destined to be The Spoils of Poynton, with its eponymous English country house modeled on Clouds, was taking shape in his mind.

Like Madeline in 1887, the chatelaine of Poynton, Adela Gereth, is a fifty-something woman of exquisite taste who has turned her home into a “complete work of art,” more appealing to those “who were really informed” than “places much grander or richer.” Through the eyes of Fleda Vetch, Mrs. Gereth’s protégée to whom she longs to bequeath the house and its array of impeccably chosen objects, we see Clouds as James did during a tour he took with Madeline:

Wandering through the clear chambers where the general effect made preferences almost as impossible as if they had been shocks, pausing at open doors where vistas were long and bland, she would, even hadn’t she already known, have discovered for herself that Poynton was the record of a life. It was written in great syllables of color and form, the tongues of other countries and the hands of rare artists. It was all France and Italy with their ages composed to rest. For England you looked out of old windows—it was England that was the wide embrace.

Though there is a northern English town called Poynton, when naming the house in his story of aesthetic fixation James was probably thinking of Edward Poynter, Georgiana Burne-Jones’ brother-in-law and a favored Souls artist. His 1886 gouache portrait of Mary still hangs at Stanway, the house she loved with every bit of Mrs. Gereth’s passion for Poynton.

The shocking culmination of the novel, Poynton’s destruction by fire, was also inspired by Clouds. In 1885, when building work was nearly finished, Percy had an encounter straight out of a James ghost story: a mysterious woman in black visited and announced that in less than three years the house would burn down. It took a little longer than predicted: nearly four years later, a housemaid left a candle in a cupboard, causing the entire place to go up in flames. No one was hurt, and much of the furniture and contents were rescued. But the house was practically gutted. Mary, who was there with her three children when it happened, wrote to Balfour:

I do grieve so for Papa and Mama I’ve aches and aches for them and I have not suffered half enough. I wish I could lighten their load—it’s too hard; all their love and labor lost, when one did so want them to enjoy the well-earned fruits of all their pains.

Possibly due to the warning, Percy had taken out extensive insurance policies, and with the help of those payouts Clouds was restored to its former glory in two years. Yet his hopes of creating an ancestral home for the ages were incompatible with the march of history. The demise of high society as an exclusive bubble of sanctioned privilege was already being heralded in the 1880s, when James compared the English upper class to the French aristocracy before the revolution. By the turn of the century, capitalists were usurping the preeminence of the born wealthy, and titled debutantes found themselves competing in the marriage market with daughters of the nouveau riche, especially Daisy Miller–like Americans.

The Great War dropped the final curtain on the old ways of the English nobility. In the interwar period, with land values plummeting and death duties increasing, many country estates were broken up and sold. The last direct inheritor of Clouds, George’s son, Perf, was killed in battle, and the house passed to a young cousin who struggled to keep it going. After being rented out for more than a decade, it was finally sold in 1936 for just £39,000.

Mary, who lost two sons in the war, held on to her beloved Stanway, where she died and was buried in 1937. She outlived Balfour by seven years; they were always close, even though he was constitutionally incapable of expressing his love. “All the things I really want to say,” he wrote to her when she was in Egypt with Blunt, “are unsayable.” Only death would very slightly lift the lid on his emotions. In the spring of 1887, before a potentially perilous trip to Ireland, he gave his sister-in-law Frances a leather pouch to be cut open “if the worst (as people euphemistically say!) should happen.” Forty-three years later, Balfour died and she and Mary opened the pouch together. It contained a small diamond brooch and a letter: Frances was to give the brooch to Mary “as from yourself” and “tell her that, at the end, if I was able to think at all, I thought of her.” It was Balfour’s most open-hearted gesture. To receive it at age sixty-seven, and from beyond the grave, was a bittersweet twist worthy of James’ own pen.