Mrs. Maude R. Rymex, marriage license clerk, 1937. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

When Yolanda Daniel and Jo Ann Martinez marched into the Merced County courthouse asking for a marriage license on the morning of January 16, 1976, local bureaucrats had no idea what to do. Although those in the office had never been asked to license a same-sex couple, California did not explicitly ban gay marriage. The law defined marriage as simply a union between “two persons.”

The county clerk’s office referred the matter up the chain of command. But the official tasked with issuing a final decision on marriage cases, a lawyer for Merced County named Russell Koch, was out of town that week. The clerk’s office placed a series of phone calls to legal minds across the county asking how to proceed. According to Dave Bultena, a lawyer who worked for Merced at the time, a representative for the vacationing county counsel rushed into the district attorney’s office later that morning “all in a huff, kind of upset,” and asked the district attorney to weigh in. “He was working up a sweat,” Bultena said. The district attorney told the man that he didn’t know what to do, either. Perhaps because of the conservatism of Merced County, few had ever given any thought to the possibility of same-sex marriage.

By the afternoon, the Superior Court judge for Merced received the last of these calls. He told the clerk’s office that neither he nor other attorneys in his office knew of a statute against same-sex marriage. The judge suggested that the clerk issue Daniel and Martinez the license.

Within the hour, the two women stood outside the county courthouse as Judge Haven Courtney—a justice of the peace—officiated their marriage ceremony. When the judge told them, “I now pronounce you man and wife,” Yolanda Daniel and Jo Ann Martinez, surrounded by half a dozen friends and a photographer for the local paper, leaned in and kissed.

In reality, there was precedent to suggest that gay marriage violated California law. In June 1970, the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church filed a lawsuit on behalf of a lesbian couple after Los Angeles County refused to issue them a marriage license, arguing that the move violated the state’s constitution. The case was quickly dismissed. And in the 1972 case Baker v. Nelson, in which a couple sued the state of Minnesota for infringement of their civil rights, the Supreme Court ruled that state bans on same-sex marriage were constitutional.

But these decisions were not widely publicized and remained unknown even to the bureaucrats who issued marriage licenses for a living. This was an era before same-sex marriage was regularly maligned as a moral threat, before the mass mobilization of the religious right during Ronald Reagan’s presidency. The cluelessness about same-sex marriage is most evident in the fact that, until the end of the 1970s, many states defined marriage using gender-neutral language that unintentionally included LGBT people. Marriage laws were made gender neutral as a haphazard way to weed out blatant gender disparities in the definition of marriage. In 1971, California revised its marriage code to remove a provision that set the age of consent for men at twenty-one and for women at eighteen. Its update said simply, “Any unmarried person of the age of eighteen years or upwards, and not otherwise disqualified, is capable of consenting to and consummating marriage,” a move legislators did not seem to consider could include LGBT people.

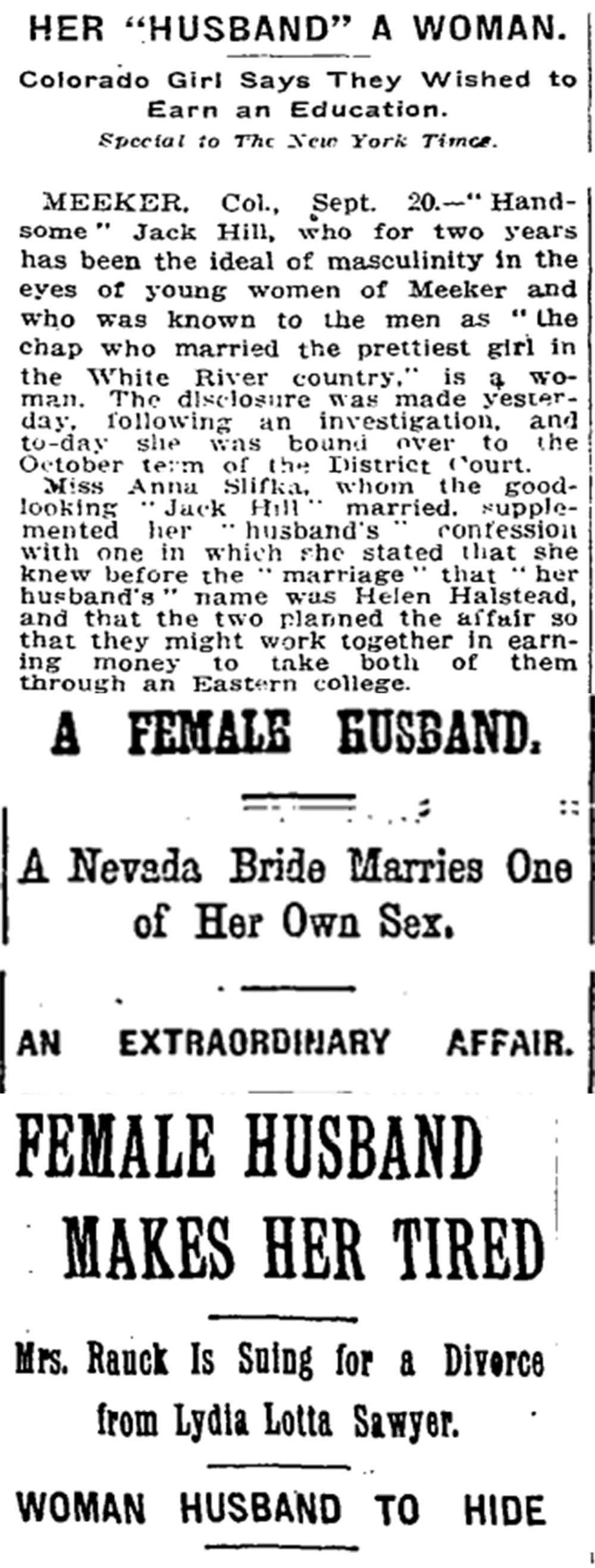

Same-sex marriage, when it was thought of at all, was most often met with a laugh or shrug—such an oddity that reports of early same-sex marriages often seemed incredulous, like the 1913 headline in the New York Times her “husband” a woman. The question of marriage was less of a moral issue than a peculiar bureaucratic dilemma.

Yolanda Daniel and Jo Ann Martinez did not seem to expect that their request for a marriage license would make waves. They knew California’s laws defined marriage in gender-neutral terms, a fact that gay activists had seized on when they staged a symbolic triple wedding in Sacramento in 1972. Though aged twenty-five and twenty-two, Daniel and Martinez had already been together for six years. That morning in January, they decided it was high time to make their union official.

“We thought we would do it the legal way,” Martinez told the Merced Sun-Star, which ran the item the next day under the headline man and wife both female, squeezed in between an announcement of a “Cinderella” ballet at a local college and news about former Nixon chief of staff H.R. Haldeman insisting he had told the FBI everything he knew about the secret tapes.

“I know a lot of people here who want to marry someone of the same sex and now I know they will say their vows. They were just waiting for someone like us to lead the way,” Martinez added. “We made it, it is now legal, and we are both very happy.” Then she kissed her new wife again. “Right on.”

Examples like theirs were not unheard of. In 1975 a sympathetic county clerk in Colorado married six same-sex couples by substituting the gender of the applicants with the word person; four years earlier, the Minnesota couple behind the Baker v. Nelson case used gender-neutral names to receive their own marriage license. Even as far back as the 1920s, entertainer Mabel Hampton described watching butch women with femme partners obtain marriage licenses in New York. They looked heterosexual enough to pass inspection by officials who had little concept of same-sex marriage in the first place. In the early nineteenth century, these marriages were common enough that in 1838, the Maine newspaper Weekly Gazette ran a story entitled another female husband?

An August 1973 article in The Advocate, centered on the marriage and subsequent divorce of Chicago socialite Randee Harris and his partner James Keenan, noted that it knew of “several other gay marriage cases.” Some of these couples received marriage licenses upon walking into their county courthouses, while others—like Harris and Keenan—wrote up legal documents emulating marriage contracts and received official approval of their marriage “after a year of legal maneuvering.”

In one famous case, a football player named Antonio Molina married a person described as a “female impersonator,” William Ert—who may have identified on the trans spectrum today but did not claim that identity at the time—in Houston in 1972. The magazine Gay Scene said that the wedding exploited a loophole in the official Texas definition of marriage: “Under Texas law, any two persons who have been granted a license may marry. It seems that the lawmakers neglected to state that they must be of the opposite sex.”

What is so striking about these early marriages is how plausible they sounded to the bureaucrats tasked with litigating them.

“The notion that same-sex marriage was unimaginable in the past was a fiction maintained in order to stabilize the norm,” said Rachel Cleves, whose book Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America recounts the story of an eighteenth-century couple who openly lived together for forty years. “In fact, stories about same-sex marriages circulated widely in Anglo-American culture for centuries, always framed as ‘unbelievable’ or ‘stranger than fiction.’ ”

Even within some churches, same-sex marriage ceremonies were common. The aforementioned Metropolitan Community Church was performing gay wedding ceremonies as far back as March 1969, months before the Stonewall riots. Although these ceremonies carried no legal weight, they demonstrate the relative normality of a tradition that, at least in recent decades, has been portrayed as an unprecedented assault on religious values.

That is not to say all of these early gay marriages lasted. Many ended in legal backlash that laid the groundwork for the modern spate of discriminatory marriage laws.

In Merced County, Jo Ann Martinez’s prediction that other same-sex couples would apply for marriage licenses turned out to be prescient. By January 22, county counsel Russell Koch returned from his ill-timed vacation in a panic. Six new couples had applied for marriage licenses, and unlike all of his colleagues in Merced, Koch believed that California law intended to prohibit same-sex marriages. Koch was not the first county attorney to argue that the intention of a marriage law overrode its gender-neutral language: in August 1970 a Louisville attorney denied marriage licenses to a lesbian couple because he argued that “the legislature never has intended to permit two practicing homosexuals or lesbians to be blessed with the sanctity of a marriage contract,” per the newspaper Gay NYC.

Koch issued a verbal opinion blocking the county clerk from issuing any more licenses. But even he had not considered the ramifications of his actions. When the Sun-Star asked “if his ruling means the Martinez–Daniel marriage is invalidated…Koch said he hadn’t really thought about that.”

A week later, on January 29, he issued a formal decision: the marriage between Daniel and Martinez should be nullified. “It takes more than a license to create a marriage,” Koch said. “My basic opinion is that under law two persons of the same sex cannot have a marriage relationship.” But he went on to clarify that this “was a legal, not moral, opinion.”

Koch’s opinion worked its way up to the California legislature and formed the basis of AB 607, which specified that marriage in California was between “a man and a woman.” California governor Jerry Brown signed the law in August 1977. (By 2005 he had begun expressing support for same-sex marriage.) Although Daniel and Martinez were never named, the Associated Press reported that the amendment was written up after “some gay couples presented marriage certificates to county clerks and asked them for licenses and legal recognition.”

Judge Haven Courtney, who had officiated the marriage between Martinez and Daniel, also saw a backlash of his own. According to Bultena, the employee in the district attorney’s office, Courtney’s opponent in an election two years later maligned Courtney for his embrace of same-sex marriage. “He used the same-sex marriage and the fact that Courtney had performed this marriage against him,” Bultena said, making Courtney one of the first officials to see the rise of a voting bloc opposed to same-sex marriage. Courtney lost the election. And although Daniel and Martinez stayed together for a few years after their marriage was nullified, a friend of the couple reported that angry locals would throw beer bottles at their shared house.

Four decades later, on June 17, 2008, two women—Kathy Hunter and Polly Bernardo—exited the Merced County courthouse to a “deluge of cheers and applause,” the Merced Sun-Star reported. The pair represented the first couple to receive a marriage license in the politically conservative Merced after a California court struck down its same-sex marriage ban earlier that week. Four other couples were also married that afternoon.

Hunter told the paper, “We’ll probably have more butterflies next Thursday when we’re actually exchanging vows.”

In a turn that might feel familiar to longtime residents of Merced, the window of legal marriage in California closed later that year, when voters passed the ballot initiative Proposition 8. But this time, Merced couldn’t strip Hunter and Bernardo of their license. And when California again legalized same-sex marriage in 2010, it seems to have been for good.