Adapted from “Art of This Century,” chapter 136 of Gotham at War: A History of New York City from 1933 to 1945, published by Oxford University Press in October 2025.

In May 1943, Peggy Guggenheim hosted a “Spring Salon for Young Artists” at the Art of This Century Gallery on West 57th Street. Guggenheim, who had inherited a modest portion of her family’s mining fortune, had opened an art gallery in London in 1938. With the aid of advisers like Marcel Duchamp, it had been a succès d’estime, and she decided to establish a museum of contemporary art. In August 1939, Guggenheim set out for Paris to arrange loans for an opening exhibit. With the outbreak of war in September she abandoned the project and shifted into full-scale collecting mode, buying paintings and sculptures at a great clip from the likes of Picasso, Ernst, Magritte, Brancusi, Giacometti, Dalí, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Tanguy, and Chagall (some of whom sold at fire-sale prices to raise cash to leave the country).

When the Nazis approached Paris in 1940, she fled south with her collection and spent the next year in Vichy France. In Marseille, she struck up an affair with Max Ernst. She also aided Varian Fry’s smuggling of artists and intellectuals out of France and herself underwrote the flight of a small group—including Ernst—that departed Lisbon by flying boat and arrived at New York’s Marine Air Terminal on July 14, 1941. Ernst, a German national, was detained on Ellis Island but was liberated through her efforts and those of Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art.

Guggenheim moved into a huge townhouse at 440 East 51st Street, just off Beekman Place overlooking the East River (the neighborhood reminded her of Paris), and installed Ernst therein. She offered him board (and bed), provided him a studio, and chauffeured him around town, but he refused to wed. Until Pearl Harbor made him an enemy alien—a status, Guggenheim pointed out, that included the possibility of being sent to an internment camp. Three weeks later, he deigned to submit to marriage.

It wouldn’t last long. Still, in the meantime, the couple’s elegant establishment became the center of a swirl of some of the greatest artists of Europe, dozens of whom had made their way to Gotham. (As Yehudi Menuhin noted: “One of the great war aims is to get to New York.”) André Breton, surrealist chieftain, was in her inner circle; indeed, she had paid for his escape from France and guaranteed him a $200-a-month stipend for his first year. In return, Breton helped catalog her massive art collection, which she’d had shipped across the Atlantic, labeled as “household goods.” Breton reconstituted his court around Guggenheim’s townhouse, and the surrealists were liberally represented at the lavish parties she threw. More generally, the presence of Chagall, Mondrian, Tanguy, Ernst, Léger, Lipchitz, Breton, and Duchamp, among many others, made it possible for New York to claim that it had—at least temporarily—supplanted Paris as capital of the art world.

The émigrés—fourteen of whom Pierre Matisse (Henri’s son) collectively fêted in a glittering “Artists in Exile” show at his 57th Street gallery in March 1942—for the most part did well in New York. They had important spokespersons there, access to the press, connections to private collectors, and relations (in some cases of long standing) with art dealers who exhibited and sold their work. Surrealist champion Julien Levy, Ernst’s representative, kept him in the public eye. Pierre Matisse, who looked after Chagall, gave him a monthly allowance of $350, rising to $700, and arranged for major showings (despite Chagall’s having raised J. Edgar Hoover’s hackles by his cozy relations with the Yiddish Communists around Morgyn Frayhayt).

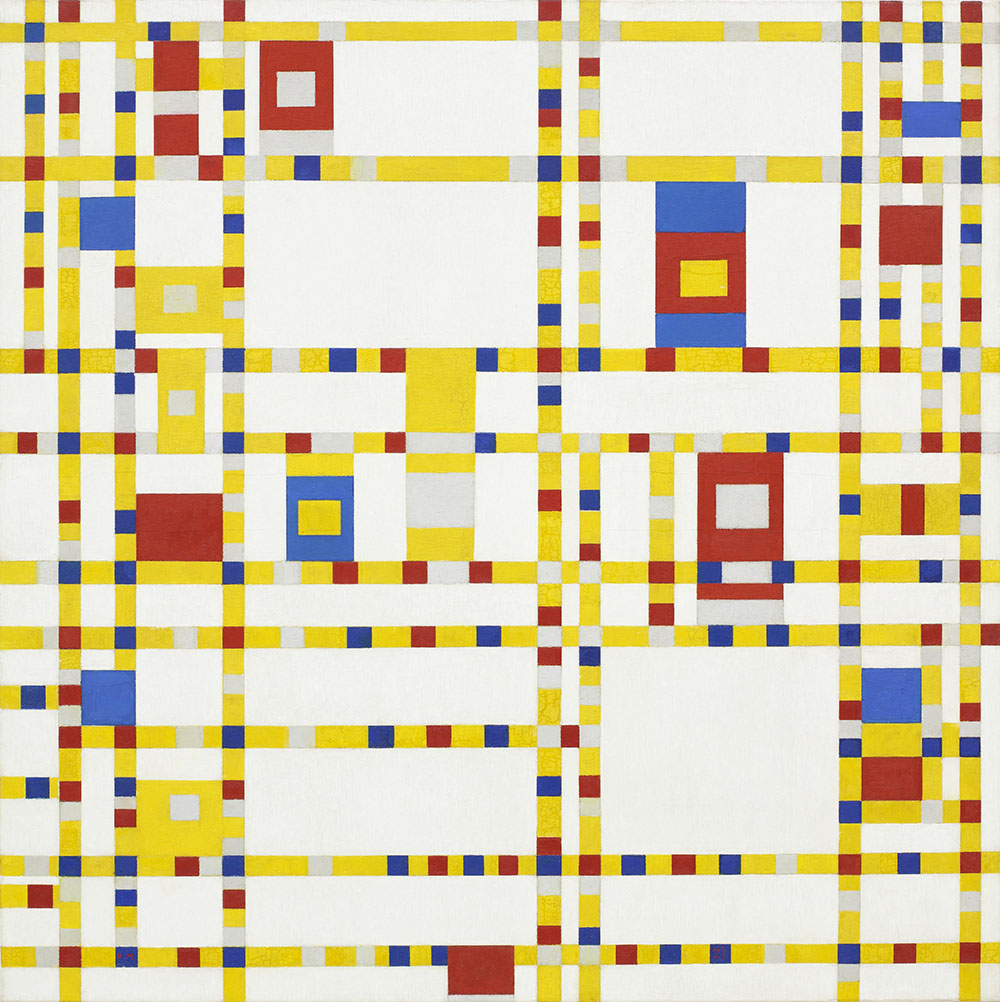

Perhaps no one was as creatively energized by the wartime city as Piet Mondrian. The Dutch artist, who arrived in September 1940 at the age of sixty-eight, fell immediately in love with New York’s architecture and flashing neon, its jazz clubs and dance halls. He was particularly fond of barrelhouse pianists Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons, whose propulsive music he heard downtown at Café Society. They inspired (as did galvanic Gotham itself) dynamic new works like Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942–43), whose buoyant network of interwoven strips pulsing with primary colors suggested an aerial view of Manhattan’s rush-hour traffic a-honk with yellow taxis. An ardent abstractionist who sought (as did Claude Lévi-Strauss) to discern universal structures beneath the buzzing confusion of surface appearances, Mondrian was enthralled by New York’s grid, that underlying matrix which channeled random urban phenomena into orderly circulatory patterns.

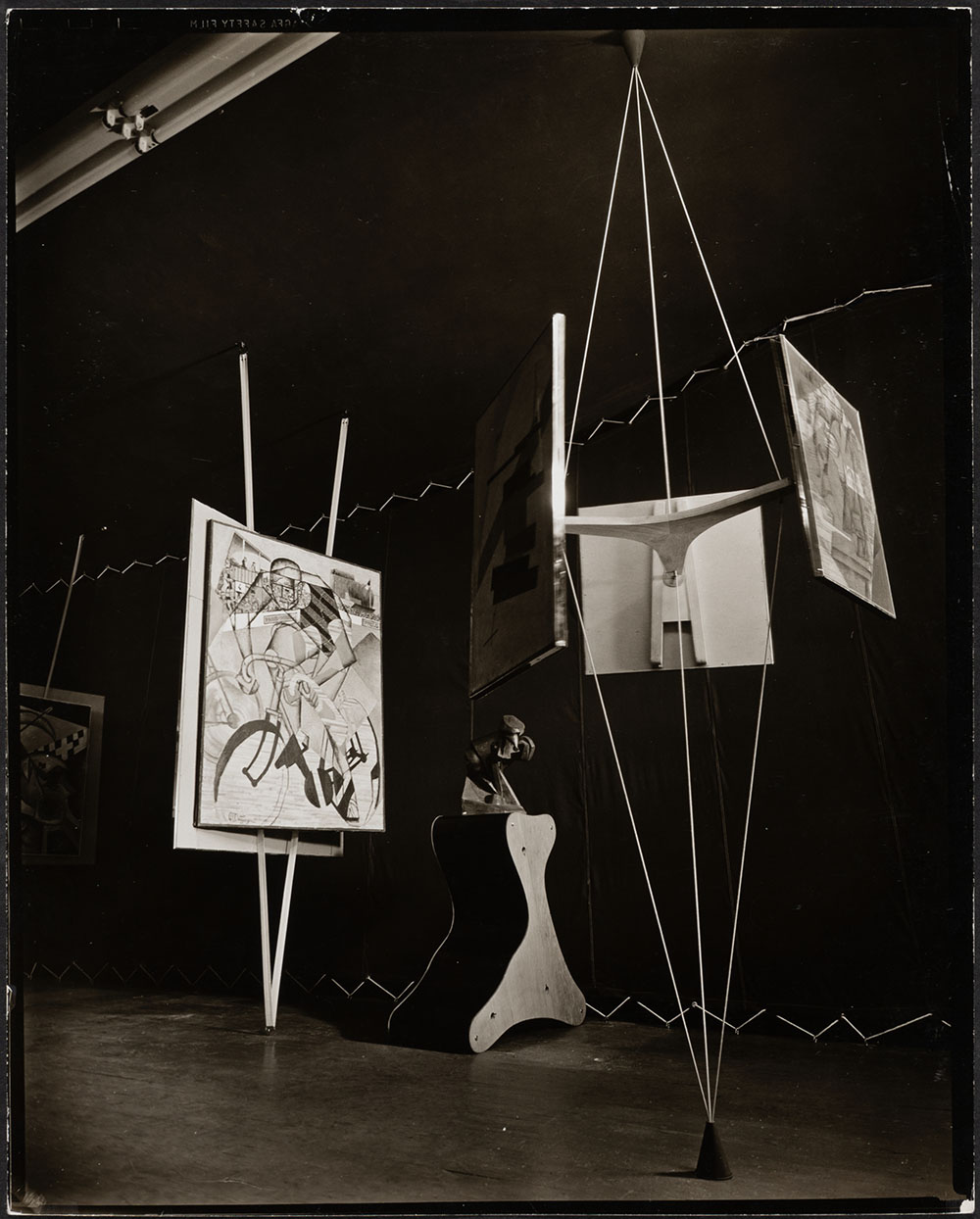

Mondrian and Breton represented opposite ends of the modern-art spectrum—the abstract and the surreal—but in New York, these European differences seemed less compelling. Guggenheim actively worked to reconcile prior aesthetic conflicts, wearing one earring by Tanguy and one by Calder, “in order,” she said, “to show my impartiality between surrealist and abstract art.” More importantly, her new Art of This Century Gallery adopted a similarly catholic approach. For her initial exhibition, she culled from her collection 171 works by artists of every major twentieth-century tendency. She was aided in this by experts like Duchamp, Barr, James Johnson Sweeney (director of MOMA’s Department of Painting and Sculpture), and Howard Putzel (the critic, collector, and gallery owner who had been one of her closest advisers since 1938). The result was a spectacular show that celebrated the rescue of Europe’s avant-garde culture and proposed, implicitly, the suitability of New York as its possible new home. The ATC’s launch was made even more spectacular by Guggenheim’s hiring of Frederick Kiesler, an innovative Viennese architect, to transform her seventh-floor loft into an exhibit space that upended traditional ways of presenting and appreciating art. Works were shown unframed,or supported by suspension columns, or mounted on sawn-off baseball bats protruding from curved gum-wood walls, or (like seven paintings by Paul Klee) placed on a wheel that revolved when a visitor tripped a light beam. Gotham had never seen anything like it.

More daring still, in the spring of 1943, Guggenheim expanded her embrace to include local New York artists who had been largely dismissed as uninteresting provincials by the snooty Surrealists. In part this was because she had recently quarreled with Breton and been ditched by Ernst for a young painter. She was also urged in this direction by her New York advisers Putzel and Sweeney, and by the now-resident Chilean painter Roberto Matta Echaurren. In April 1943, accordingly, she announced that her gallery would hold a competitive salon in May for American artists under the age of thirty-five. Crowds of them showed up at 57th Street carrying canvases they hoped would be considered by a jury that consisted of Guggenheim’s New York experts and two Europeans, Duchamp and Mondrian.

On judgment day, Mondrian was the first to arrive, and the elegantly attired Dutchman began perambulating the paintings. At one point he stopped walking and began staring at a particular work. Guggenheim wandered over. “Pretty awful, isn’t it?” she asked. “That’s not painting, is it?” Mondrian did not respond. She walked away. Twenty minutes later she returned to find him still rooted before the same painting, his right hand thoughtfully stroking his chin. Guggenheim again distanced herself from the work and the artist. “There is absolutely no discipline at all,” she complained. “This young man has serious problems, and painting is one of them. I don’t think he’s going to be included, and that is embarrassing because Putzel and Matta think very highly of him.”

Finally, the mesmerized Mondrian responded: “Peggy,” he said, “I have a feeling that this may be the most exciting painting that I have seen in a long, long time, here or in Europe.” Guggenheim, astounded but nimble, turned on the proverbial dime. She raced off and began dragging other jurors over to the painting, saying: “I want you to see something very exciting. It’s by someone called Pollock.”

Jackson Pollock, a farm boy from Wyoming, had been living in New York since 1930 when he had come at the age of eighteen to study at the Art Students League with Thomas Hart Benton. He’d also (not having much money) been attracted to the free art courses offered by the Greenwich and Henry Street settlement houses. As the Depression deepened, Pollock, unable to make ends meet, was rescued, like many other floundering artists, by a governmental lifeline. In early 1935 he was hired by the Parks Department to restore civic monuments (he scoured, among others, the Firemen’s Memorial at Riverside Drive and West 100th Street and the equestrian Washington in Union Square). Later that year he was taken on board by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project as a mural assistant, a regularly salaried position that, with occasional interregnums, would provide him with economic security for most of the next seven years.

During this period Pollock soaked up the host of artistic influences then to be found in the cornucopian metropolis. He was captivated by the Mexican muralists. In 1930 Pollock had met José Clemente Orozco while working on murals for the New School cafeteria at 66 West 12th Street (and in 1936 he would travel up to Dartmouth College to see the Orozcos there). In 1933 he watched Diego Rivera paint his doomed mural at Rockefeller Center.

In 1936 Pollock joined the Experimental Workshop—billed as “A Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art”—that David Alfaro Siqueiros set up in his huge loft at 5 West 14th Street; members worked with new industrial materials like Duco (a synthetic resin paint developed for automobiles), pouring it onto panels laid out on the floor, or using sticks to splatter and drip it on the surface below.

He visited all the great MOMA exhibitions—“Cubism and Abstract Art,” “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” and the Picasso retrospective (as well as Picasso’s Guernica at the Valentine Gallery, returning to see it repeatedly). He was fascinated, too, by MOMA’s colossal “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art” exhibition of 1940, arranged with help from Nelson Rockefeller. It featured pre-Columbian artifacts but also brought Orozco back to New York, just after the Nazis blitzkrieged France, to paint in public a portable mural called Dive Bomber and Tank, with Pollock among the onlookers. Pollock also attended the next year’s mammoth “Indian Art of the United States” exhibition, watching as Navajo artists executed sand paintings by allowing sand of various colors to trickle through their hands to the gallery floor.

Deeply taken with Native American art, Pollock immersed himself, too, in Franz Boas’ Northwest Coast collection at the American Museum of Natural History and in the Museum of the American Indian’s trove of artifacts, from whose Bronx storehouse Ernst, Lévi-Strauss, and Breton were making withdrawals. And he prowled the Midtown galleries, attending the Expressionist shows of Klee, Kandinsky, and Max Beckmann at Paul Rosenberg’s gallery; the exhibitions of Joan Miró at the Valentine and the Matisse; and the displays of Surrealists Ernst and Tanguy at Julien Levy’s.

If Pollock’s intake was rich and varied, his output, though occasionally remarkable, remained inchoate and intermittent. He engaged in self-destructive drunken binges, bar brawls, and violent outbursts during which he might carve up his own canvases; alternating these with extensive periods of depression, alcoholic stupor, and nights spent sleeping in the gutter. In 1937 he began four years of Jungian psychotherapy. The next year, at his brother’s urging, he quasi-voluntarily institutionalized himself as a charity patient at New York Hospital’s asylum in White Plains, where affluent Gotham families sent their black sheep to dry out; he resumed drinking as soon as he left. In 1941, after his latest therapist wrote his draft board suggesting Pollock be referred for a medical examination, he was found psychiatrically unfit to serve and declared 4F.

Nineteen forty-one, however, was the year his life began to turn around, thanks to making some crucial metropolitan connections. The previous year he had encountered John Graham, a painter, critic, collector, and dealer of some notoriety in New York. Descended from minor Polish nobility, Graham (né Dombrowski) had adopted Russia as his homeland, served the tsar as a cavalry officer, then fled to Gotham after the Revolution.

In the 1920s Graham took up painting, first studying under John Sloan at the Art Students League, then traveling frequently to Paris, where he became a devotee of Cubism and (so he claimed) an intimate of Picasso. His embellished autobiography, eccentric opinions, and dandyish self-presentation gave him cosmopolitan cachet among status-anxious local artists, among whom he promoted Surrealist techniques like “automatic writing.” However, what really secured Graham’s reputation was his ability to spot many of the city’s most promising young painters before others did and then promote them. He was not only the first to acclaim Pollock a genius in the rough, he acted on that assertion by including the artist in an exhibition pairing French and American painters, held at the McMillen Gallery (148 East 55th) in January 1942, hanging his work alongside that of Picasso and Matisse.

That same McMillen exhibition included another emerging New York artist, Lee Krasner, who introduced herself to Pollock, promptly fell in love with him, and proceeded to take him in hand (at considerable cost to her own career). Born Lena Krassner in 1908 to an immigrant Russian Jewish couple in East New York, Krasner had studied art at Washington Irving High School, the Woman’s Art School at Cooper Union, the Art Students League, and the National Academy of Design.

In 1926 she departed Brooklyn to begin life as an artist in Manhattan, only to be confronted, in 1929, with collapsing stock and art markets. After supporting herself for a time as a model and waitress, she was hired in 1934 by the Public Works of Art Project, and then was taken on by the Federal Art Project as a mural assistant. Shortly after she met Pollock, the FAP was reorganized as the Graphics Section of the War Services Division, and in the summer of 1942 Krasner was set to design window displays that promoted courses at city colleges; she picked Pollock as her assistant. In October she was redeployed to creating Navy recruiting posters; she hired Pollock for the team.

Krasner, far better wired into the New York art world than Pollock, also began introducing him to influential figures, starting with her teacher Hans Hofmann. A celebrated German émigré painter, who really was a friend of Picasso and Matisse, Hofmann had moved to Gotham in 1932 and in 1933 opened a school and atelier at 52 West Eighth Street at which he began transmitting to New York artists the modernist principles of Munich and Paris. Krasner then arranged visits to other members of Hofmann’s circle, which led in spring 1942 to a visit to Pollock’s studio from MOMA’s James Johnson Sweeney, followed by another that summer from Howard Putzel, and subsequently to Peggy Guggenheim’s invitation to her 1943 Spring Salon.

That invitation came just in time. As Guggenheim was opening her gallery, the WPA was being terminated, and in January 1943, both Krasner and Pollock were pitched into unemployment. In extremis, Pollock turned to the Baroness Hilla Rebay, a German artist who, while painting a portrait of Solomon R. Guggenheim, Peggy’s uncle, had convinced him to establish a Museum of Non-Objective Art that would feature artists like Kandinsky, Klee, and Mondrian, and to appoint her as its director.

Opened in 1939 in a former automobile showroom at 24 East 54th Street, the museum was a temple of high art, with piped-in Bach—the utter opposite of Guggenheim’s flashy gallery. The baroness loathed Peggy, believing she’d sullied the family name by propagating “mediocrity, if not trash.” To help run a museum that she hoped would unblot the Guggenheim escutcheon, Rebay hired young artists. Pollock—after writing, with Krasner’s help, a suitably ingratiating letter—was taken on to make frames and run the freight elevator. He started work May 8, 1943.

Days later, lightning struck when—now koshered by Mondrian—Guggenheim adopted him as a protégé, and he began a spectacular ascent to stardom. First, she signed a contract guaranteeing him a year’s worth of $150-a-month cash payments against future sales, which allowed him to quit the baroness before she could fire him for going over to the enemy. Guggenheim also commissioned Pollock to paint a nineteen-foot-long mural for the entrance hall of her new East 61st Street duplex apartment. And she gave him his first solo show (the first for any American artist at the ATC), which opened on November 8, 1943.

His exhibit garnered favorable reviews—Robert Coates called him “an authentic discovery” in the New Yorker—as did the mural, which he painted with volcanic speed in a fifteen-hour all-nighter early in January 1944. In April 1944, Sweeney penned a laudatory article for Harper’s Bazaar called “Five American Painters,” putting Pollock in his featured quintet and providing a full-color reproduction of The She Wolf, one of his solo exhibition’s offerings. In May that same painting was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art (thanks more to Sweeney than to Barr, whose troth remained plighted to Europe).

Pollock now acquired a personal champion. Clement Greenberg, formerly a literary critic at Partisan Review, had switched in 1942 to doing art criticism for The Nation. To prepare for his new calling he took a summer crash course at the Art Students League, attended lectures by Hans Hofmann at his Eighth Street atelier, and was taken around the galleries by Hofmann’s pupil Lee Krasner—who, of course, introduced him to Pollock. Greenberg became a fierce partisan, especially after seeing his mural for Guggenheim and his second ATC show, held in April 1945, after which he pronounced Pollock “the strongest painter of his generation.”

In no small part this was because he saw Pollock as an agent of his own ferocious ambition for American art to counter the humiliating authority of European art by eclipsing it. “I wanted,” Greenberg recalled, “to see somebody come along who could match the French so we could stop being minor painters over here.” This nationalist ambition, while not shared by Pollock himself, resonated strongly among other critics in the jingoistic war years. Pollock’s “abstractions are free of Paris,” Art News declared, “and contain a disciplined American fury.” Greenberg was not alone in seeing the glowering Westerner as a good candidate for the role of Great American Painter.

Pollock would not have to bear such burdensome expectations alone, because he was no more an isolated genius than was Charlie Parker. He was, rather, part of a generation of young downtown painters similar to the set of young uptown musicians, of whom Parker was but one. It was the cohorts, not the individuals, that would transform their respective terrains. (Parker’s bop revolution, Pollock told Krasner, “was the only other really creative thing happening in this country.”)

Each member of what critic Coates would at war’s end call the Abstract Expressionists, a.k.a. the New York School, had come to Gotham for different but often overlapping reasons. And once here, their mutual encounters spawned a network of friendships and associations that would gel into something more than the sum of its parts.

Some started out in New York, like Lee Krasner, though for her—as for the literary critic Alfred Kazin—the journey across the East River from Brooklyn was itself as momentous a migration as any that passed through Ellis Island. Barnett Newman and Adolph Gottlieb were second-generation Manhattanites, the former born on Cherry Street in 1905 to Russian Jewish immigrants, the latter born in 1903 on East 10th Street, across from Tompkins Square, to immigrant Jewish Czechs. Most, however, started elsewhere. Willem de Kooning, born in Rotterdam in 1904, arrived in Newport News, Virginia, in 1926, as a stowaway on an English ship, and made his way north to Hoboken’s Dutch community, where he worked for five months as a house painter before moving to Manhattan in 1927. Vosdanik Manoog Adoian, born around 1904, fled with his family from their home village in Turkish Armenia to escape the genocide; he arrived in the U.S. in 1920 and in Greenwich Village in 1924, having adopted the name Arshile (after Achilles) Gorky (after the writer). William Baziotes, born in 1912 to Greek parents in Pittsburgh, was employed in a glass factory in Reading, Pennsylvania, when he visited New York in 1931, saw a comprehensive Matisse exhibition at MOMA, then packed up in 1933 and moved to Gotham to study painting. Marcus Rothkowitz, born in 1903 in Dvinsk, Russia, escaped his Cossack-ridden country to the U.S. in 1913, when his father emigrated to avoid the draft; he arrived in New York in 1923 to work in the garment industry and in 1940 changed his name to Mark Rothko, fearing the surging anti-Semitism of his adopted country. Robert Motherwell hailed from Aberdeen, Washington, where he was born in 1915. His father, director of the Wells Fargo Bank, could afford to send him to study philosophy at Stanford and then Harvard, but in 1940 Robert shifted his focus to art history and moved to New York to study at Columbia with Meyer Schapiro, who encouraged him to become a painter himself.

Like Pollock, many of these would-be artists were drawn to Gotham to study art, and many attended formal institutions like the Art Students League, National Academy of Design, New School of Design, Parsons School of Design, Cooper Union, Grand Central School of Art, Educational Alliance Art School, and the New School for Social Research’s print workshop, Atelier 17—places where they could work with New York artists of the preceding generation like Robert Henri, John Sloan, and Max Weber.

They also established links to unaffiliated artists like John Graham, who in addition to mentoring Pollock was an important influence on De Kooning, Gorky, Gottlieb, Krasner, Newman, and Rothko. Hans Hofmann was held in similarly high regard. So was Milton Avery (Gottlieb, Newman, and Rothko were among those who regularly gathered at Avery’s home to study his work and participate in sketching sessions). And so was Matta, who introduced Baziotes to Motherwell— both of them, together with Pollock and Krasner, met at Matta’s studio to collaborate on collective “automatic” drawings, Pollock less enthusiastically than the others.

New York’s museums and galleries were another great draw. They provided crucial portals to European modernist masters (De Kooning said seeing Guernica was crucial to his development) and to alternative cultural traditions (most flocked to the MOMA’s Mexican and Indian art exhibitions).

More practically, they were attracted by Gotham’s cheap housing. They settled, overwhelmingly, into downtown Manhattan, where they rented (at times shared) rooms in the cold-water flats and walk-up apartments of Chelsea, Union Square, and Greenwich Village—the bohemian haunt of artists and writers since the 1890s. Here they could drop in on one another’s studios and chat about work in progress (few had phones), then continue their conversation at nearby cheap eateries, some of hoary vintage, like the Pepper Pot Inn, Minetta Tavern, Jumble Shop, and Romany Marie’s, as well as various Village coffee shops, local Syrian, Greek, and Italian restaurants, and cafeterias like the Waldorf or Stewart’s. More serendipitously, given the density of artists per square mile, they might run into one another ambling around Washington Square, which was where De Kooning first encountered Rothko, when the two sat down coincidentally on the same park bench.

The city also provided fledgling artists with jobs as cutters or bookkeepers in the garment biz, as art teachers at professional or public schools, or as commercial artists, itself a vast and varied field in Gotham. Thus De Kooning held down jobs at Eastman Brothers, an all-purpose design factory that crafted and constructed anything from stage sets for nearby Broadway theaters to Art Deco stained-glass windows; at A.S. Beck, a chain of shoe stores for which he whipped up window displays; at assorted outfits that needed stenciling or sign painting; and he produced occasional ads, like a fashion display of cameo busts with different hairstyles for Harper’s Bazaar, and a come-on for Model Pipe Tobacco in Life magazine.

During the Depression, when jobs for artists turned scarce, New York and the feds provided governmental aid. The Treasury Relief Art Project, which commissioned quality works to decorate federal buildings, selected (among others) Rothko, Avery, De Kooning, Pollock, and Gorky along with Ad Reinhardt, David Smith, and Louise Nevelson. The WPA’s Federal Art Project employed (besides Krasner and Pollock) Gorky (who painted murals for Newark Airport), Baziotes (who taught children art at the Queens Museum), and De Kooning (who worked on murals in Williamsburg), among many others. The WPA did more than keep food on the table. It allowed many artists, for the first time in their lives, to practice their craft full time. And by bringing them together in such numbers, it midwifed an artistic community where before there had been only isolated circles and provided its members with a degree of confidence and empowerment they had never experienced, thus facilitating their great leap forward during the war years.

All was not sweetness and light in this FAP community, however. It was wracked by many of the same divisions that cleft the Popular Front. The Moscow Trials and Nazi–Soviet Pact and invasion of Finland schismed the art world, with Philip Evergood, Max Weber, Raphael Soyer, Hugo Gellert, and Stuart Davis generally on one side, while Rothko, Gottlieb, Newman, and Avery were among those who followed Meyer Schapiro out of the Communist Party–dominated American Artists’ Congress and into a rival Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. Personal discomfort at dogmatic rhetoric and cultural diktats partly explained these departures, but the fissures ran along aesthetic fault lines as well, with one side combining modern expressionist techniques with a social justice narrative, the other finding that linkage an artistic dead end.

When Matta asked, “Are there any guys on the WPA who are interested in modern art and not in all that social realist crap?” it was members of the nascent New York School who responded affirmatively. In a 1943 manifesto, Rothko and Gottlieb placed “social pictures” in the same cornball category as “pictures for the home,” pictures “for over the mantle,” and “pictures of the American scene.” When the socially conscious artists denounced the abstractionists as ivory tower aesthetes in retreat from political engagement, the latter responded by calling them “social realists”—linking them to Soviet-style socialist realism with which they had little in common—and branding their art as mere pictorial propaganda, ineffective even on its own terms. As had Trotsky in his 1938 Partisan Review essay “Art and Politics in Our Epoch,” they argued that only an unfettered independent art could subvert customary ways of seeing and thus be truly revolutionary. Hitler could live with representational art, they noted; it was the avant-garde he hated and feared.

During the war years, this combination of physical proximity, aesthetic propinquity, shared workplace and WPA experiences, and similar political sensibilities helped downtown artists coalesce into a community. Its members encouraged one another’s innovations and mutually validated artistic practices that broke in significant ways from Depression-era realism and European-style modernism. Finding their own voice just as the Europeans arrived allowed them (like their generational peers in the field of physics) to be invigorated and validated rather than undercut and overwhelmed by the eminent émigrés.

The war was also the moment when artists lost government sponsorship and were forced to rely on the private art market. The transition, though long foreseen, was still disruptive, and was made more jarring by the way WPA artworks were jettisoned as unceremoniously as were WPA artists. In December 1943 the government removed thousands of FAP oil paintings from their stretchers and auctioned them off, by the pound, at a Flushing warehouse. A plumber bought the entire lot to use for insulating pipes, only to discover that when pipes got hot, the paint began to stink. He sold the canvases to a junk dealer, who then sold them to the Roberts Book Company on Canal Street, where they were heaped on long tables in the back room, from which canvases by socially conscious artists like Alice Neel, and those of Pollock, Avery, and Rothko, could be picked up by buyers—in some cases the artists themselves—for $3 a pop.

As government patronage ended, the private art market took off, powered by wartime prosperity. With shopping expeditions to Europe foreclosed, wealthy art collectors were obliged to buy locally. So were investors seeking shelter from rising inflation, and ordinary consumers with money to spend but with ever fewer commodities (given wartime rationing) on which to spend it. Their collective purchases triggered an “art boom” in New York, the first one not tied in some way to Paris. Parke-Bernet Galleries’ public sales shot from $2.5 million in 1939 to $4 million in 1942, to $6.5 million in 1945. Private gallery sales jumped 37 percent between 1944 and 1945.

The downtown artists did reasonably well in this climate, thanks in large part to Peggy Guggenheim, who had the money and prestige to force the market to pay attention to them. She continued to promote Pollock among her circle of wealthy collectors and patrons, though she did find her protégé “rather difficult.” He “drank too much,” she recalled, “and became so unpleasant, one might say devilish,” that he seemed “like a trapped animal who should never have left the prairies of Wyoming.” Somewhat to his dismay, Guggenheim started touting other “discoveries,” giving solo debut shows in 1944–45 to Baziotes, Motherwell, Rothko, and others, while Julien Levy launched Gorky, and Howard Putzel promoted Gottlieb at his new Gallery 67.

Several tastemakers and market leaders, noting the downtowners filtering into Midtown, called attention to the phenomenon itself. Greenberg argued that a revolution was in progress in the art world and claimed that the future of American painting rested in the hands of artists like Pollock, Baziotes, and Motherwell.

Samuel Kootz agreed. Formerly an advertising and public relations executive, then a silk converter (in which role he’d commissioned Stuart Davis to design scarves), and then a patron and dealer with Baziotes and Motherwell his first protégés, Kootz declared in his 1943 book, New Frontiers in American Painting, that American art was in the thick of a “revolution.” Similarly, Sidney Janis, a former shirt manufacturer turned art collector (he owned works by Picasso, Matisse, and Mondrian), had begun by visiting the individual studios of De Kooning, Gorky, and Pollock, when they were still largely unknown, and in 1944, he wrote about their movement as a whole. In his book Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, Janis unapologetically discussed works by Baziotes, De Kooning, Gottlieb, Hofmann, Motherwell, Pollock, and Rothko, alongside those of Braque, Chagall, Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Picasso.

By 1945, encouraged by such critical certification, wealthy collectors—many of them (as Meyer Schapiro noted) “young people with inherited incomes”—were purchasing Abstract Expressionists. Both Janis and Kootz would soon open galleries that catered to this demographic.

Museums were slower to climb on the AbEx bandwagon. MOMA people liked to define their institution as young, liberal, and dynamic, especially in contrast to the fusty Metropolitan, which they referred to as the “mausoleum uptown.” (There was little love lost from north to south either: Metropolitan chief Francis Henry Taylor referred to MOMA as “that whorehouse on 53rd Street.”) But the Modern remained Eurocentric, to the dismay of avant-garde radicals in the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, which picketed MOMA in 1942, 1943, and 1944, denouncing it as insufficiently inclusive of American modernists. Still, the mandate of heaven was shifting somewhat, as evidenced by MOMA-mounted exhibitions, like one on Alexander Calder, about which the artist would say that “whatever my success has been, [it was] greatly as a result of the show I had at MOMA in 1943.”

The new artists did less well in the emerging middle-class art market, which, having been summoned into being by the many WPA shows aimed at popular audiences, was now spurred onward by war-related activities.

In January 1942, twenty-one of the city’s leading arts institutions, following the lead of their English counterparts, came together to form Artists for Victory, Inc., whose goal was to “render effective the talents and abilities of artists” in prosecuting the war. Headquartered at 101 Park Avenue and led by Hobart Nichols (president of the National Academy of Design), the group, which represented over 10,000 painters, sculptors, designers, and printmakers nationwide, proceeded to canvass, recruit, and classify its members, then connect them with military, business, and governmental agencies in need of war-related art work.

Artists for Victory also sponsored competitive exhibitions aimed at keeping the arts alive and boosting national morale. The initial one, opened on the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor, was held at the Metropolitan Museum, which set up a $52,000 fund to purchase forty-two works for its collection from among the winners. An immense undertaking—1,418 works, in all media, flooded in from across the country—it filled twenty-eight of the museum’s galleries, which had been largely emptied when its own works had been bundled off to Whitemarsh Hall, an estate in Pennsylvania, for safekeeping; they would not return until 1944.

Another Artists for Victory competition, for printmakers only, focused on “America in the War,” with artists invited to contribute works in five categories: Heroes of the Fighting Front, Action on the Fighting Front, Heroes of the Home Front, The Enemy, and The Victory and Peace to Follow. When it opened on October 4, 1943, at the Kennedy Galleries, many of the contributions came from first-time exhibitors, almost a third of them women.

The Museum of Modern Art did much the same. It launched an Armed Services Program that—often under contract to the Office of War Information or Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of Inter-American Affairs—mounted exhibits like “Wartime Housing,” “Anti-Hoarding Pictures by New York School Children,” and, in June 1942, “Road to Victory,” which featured photographic images assembled by Lieutenant Commander Edward Steichen (on loan from the Navy), accompanied by poems from Steichen’s brother-in-law, Carl Sandburg. It drew 100,000 visitors (men in uniform were admitted free) and received exultant reviews from critics ranging from the New York Times to PM and the Daily Worker.

Some art dealers, eyeing these audiences, set out to develop sales methods that could reach such markets. Realizing that unsophisticated buyers were reluctant to go to galleries, where they might be outsmarted and fleeced, they sought ways to desanctify art objects and turn them into ordinary consumer goods: advertisements, sales through artists cooperatives, buying by mail, working with popular magazines like Life, or allying with department stores. Sam Kootz collaborated with Macy’s on a 1942 exhibition and sale of “Contemporary American Paintings,” which had clerks selling to customers, rather than gallery experts selling to clients. The ads promised there would be many well-known artists! and also some brilliant discoveries among the 179 canvases by seventy-two artists, including “expressionists, surrealists, abstractionists” and members of “many other schools.” And while the paintings were on sale at rock-bottom prices, ranging from $24.97 to $249 (the two Rothkos were priced at under $200 apiece), buyers could nevertheless “be assured that any one you choose will possess real merit.” Gimbels riposted with a sale of William Randolph Hearst’s art collection (which fetched over $4 million); Macy’s volleyed back with a show of Old Masters (one third down, take months to pay); and Gimbels responded by opening a permanent art department that featured a Rembrandt for only $9,999.

It would remain to be seen if Clement Greenberg and others were correct in believing that New York might replace Paris as the capital of modern art, or if Guggenheim’s coterie of artists would supplant their socially conscious rivals. However, what did seem clear was the city’s emergence as the supreme marketplace for contemporary artists and that the war-engendered expansion of the fine-art business might allow it to take its place as the seventh component—alongside radio, recording, press, publishing, music, and drama—of the city’s burgeoning culture industry.

From Gotham at War: A History of New York City from 1933 to 1945. Copyright © 2025 by Mike Wallace. Published by Oxford University Press, 2025. Reprinted by permission of the author and Oxford University Press.