An 1873 law named for anti-obscenity campaigner Anthony Comstock deemed information about contraception too obscene for publication. Activist Angela Heywood argued against the law in an 1893 article: “Is it ‘proper,’ ‘polite,’ for men, real he men, to go to Washington to say, by penal law, fines, and imprisonment, whether woman may continue her natural right to wash, rinse, or wipe out her own vaginal body opening—as well as legislate when she may blow her nose, dry her eyes, or nurse her babe?”

Despite an increase in legal punishments for women who sought birth control and abortions across much of Europe, the twelfth-century nun Hildegard of Bingen shared remedies for “retention of the menses” in her medical texts. This way of classifying the drugs, historian Etienne van de Walle wrote in 1997, “created a zone of opportunity for women who resolved to terminate a pregnancy.”

When copying manuscripts of Dioscorides’ first-century medico-botanical handbook De materia medica, medieval scribes sometimes added marginal comments noting any purported contraceptive or abortifacient properties unmentioned in the original text. Around 1310 Peter of Abano added a note to the entry concerning an herb called asarus, explaining that “uninformed people” take it before sex to prevent conception.

Often calling themselves fortune-tellers and astrologists, nineteenth-century sellers of contraception and abortifacients resorted to euphemisms and redactions to advertise their wares. An 1839 advertisement in the New York Sun described a pill designed to “produce a******n”; later in the century, birth-control advocate Edward Bliss Foote advertised an abortion implement as an “impregnating syringe” meant for “married women only.”

In 1933 birth-control activist Margaret Sanger deliberately broke a law prohibiting the importation of contraceptives by having 120 barrier devices sent from Japan to one of her clinics. In the resulting United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries, a federal judge ruled in the clinic’s favor, arguing that the pessaries “might also be capable of legitimate uses.”

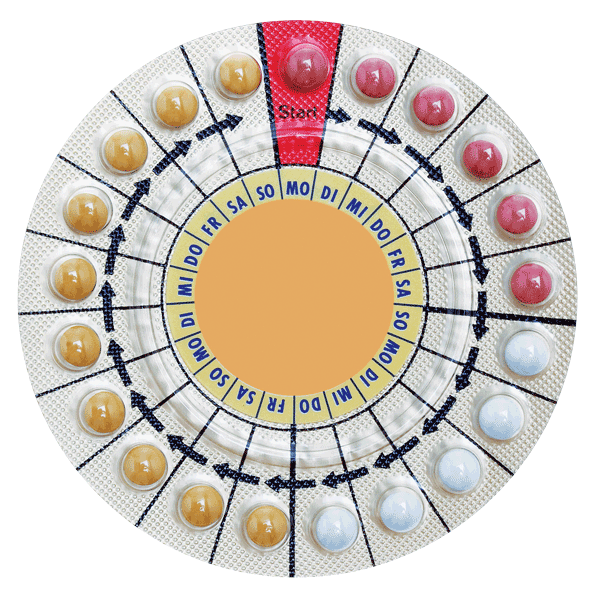

The FDA approved the first commercially available birth-control pill in 1960. “I would never agree that the pill really liberates women,” Toni Cade Bambara wrote nine years later, “but the pill gives her choice, gives her control over at least some of the major events in her life. And it gives her time to fight for liberation in those other areas.”

Many American country-music radio stations refused to play Loretta Lynn’s 1975 song “The Pill,” which includes the lyrics “All I’ve seen of this old world is a bed and a doctor bill / I’m tearing down your brooder house ’cause now I’ve got the pill.” Lynn said in an interview that rural doctors told her the song “had done more to promote rural acceptance of birth control than any official medical or social-services efforts.”

In 1996 Bill Clinton signed into law a $250 million federal program offering states funding over five years to establish and support abstinence-only sex-education programs in public schools. The only state to refuse the funding in the program’s first year was California. In subsequent years fifteen additional states refused further funding, opting instead to return to comprehensive sex-education curricula that cover the proper use of birth-control methods.