2018

2018

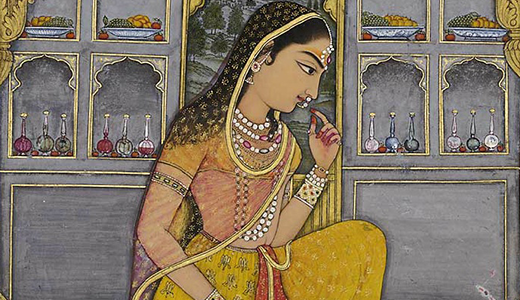

Padmini, c. 1765. National Library of France.

The film Padmaavat, which was believed to show a sex scene between Hindu queen Padmini and Muslim ruler Alauddin Khilji, sparked an intense backlash all over India that began long before the movie appeared in theaters this Thursday. Protesters have thrown stones at school buses, burned tires, and threatened to behead actors, yet Padmaavat—one of the most expensive Bollywood movies ever made—does not include the rumored scene. The Los Angeles Times notes that the film has received lukewarm reviews, some concluding that it is in fact somewhat dull.

But rumors that the film besmirched the Rajputs’ honor did not die, egged on by leaders of a fringe group known as the Rajput Karni Sena.

Last January, its followers stormed a historic fort in northern India where the movie was shooting and roughed up [director Sanjay Leela] Bhansali and his crew. The group also threatened to chop off the nose of actress Deepika Padukone, who plays the queen.

This month, one leader of the group in the northwestern state of Rajasthan claimed that 1,900 women had signed up to immolate themselves—in the manner of the fictional queen—if the movie wasn’t banned.

Producers delayed the original December 1 release date, slightly altered the title, and added a disclaimer that the film does not claim historical accuracy. India’s Supreme Court then got involved, ruling that states could not block the film because authorities had an obligation to ensure security.

Still, the Multiplex Association of India, an industry body that represents most major theaters nationwide, said this week that its members in four states would not show the movie “in view of the prevailing law and order situation.”

1929

1929

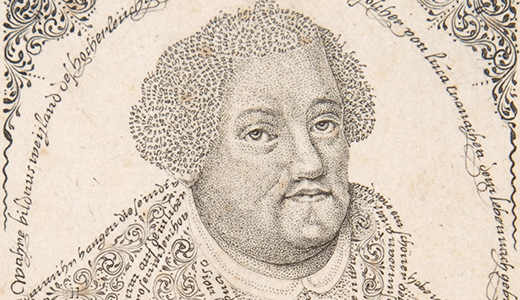

Portrait of Martin Luther, by Johann Michael Püchler, c. 1700. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Jean A. Bonna Gift, 2007.

In 1929 Londoners planning to attend a private screening of the German film Martin Luther learned the showing had been canceled by a censor after they found…a note on the door of the theater. In 1956 another German film based on the life of Martin Luther faced bans and protests from Roman Catholics in the U.S. and Quebec. These actions led to Protestant protests geared at keeping the film in theaters and on television. Decades later religious groups and leaders balked at the 1988 release of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. Thousands of protesters gathered in Los Angeles to try and stop the film; others handed out literature at screenings or spray-painted threats aimed at Universal Studios executives on theaters that weren’t even showing the film. According to the Los Angeles Times, Mother Teresa said, through a spokesperson, that enough Catholic prayers would ensure that “Our Blessed Mother will see that this film is removed from your land.” In a later Times story one ticket buyer explained that he had gone to see the movie because of the brouhaha: “No one is going to tell me what I can or can’t see.” Still, a moral conflagration may not be enough to save a tepid film. Here’s what the Spectator had to say over the protests caused by Martin Luther in 1929:

This German film was considered to be “unsuitable for exhibition in this country” because, in the opinion, of the censors, the subject was likely "to offend and antagonize large sections of the people of Great Britain.” In other words, the members of the Roman Catholic Church. The story of Martin Luther’s dissension from the Church of Rome can be read in every history book. If this story had been presented—as it could have been presented—in a way which would stir the emotions of those who witnessed it, the action of the [British Board of Film Censors] would have been more comprehensible. But this film, although dealing with a subject of intense and universal interest, fails to create the illusion of the great Reformist movement in its picturesque, medieval setting; it is so spiritually cold and uninspiring that I should be very much surprised if either Roman Catholics or even members of the Protestant Alliance would feel very moved by it.