2017

2017

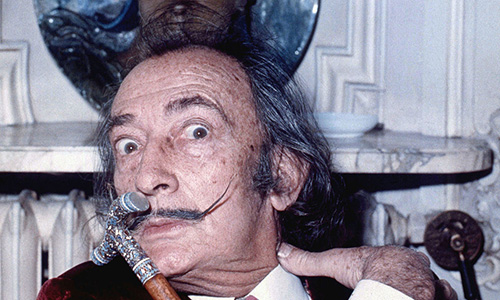

Salvador Dalí at Le Meurice, Paris, 1972.

Known for his painting The Persistence of Memory, which features melting clocks thought to represent the relativity of time, surrealist artist and icon Salvador Dalí died in 1989. “I don’t do drugs, I am drugs,” he once said, part of a long legacy of self-promotion. Dalí is often remembered for his meticulously groomed mustache, which in 1954 inspired photographer Philippe Halsman to immortalize his facial hair in the book Dalí’s Mustache. More than half a century later, his moustache remains (literally) immortalized.

The BBC reports:

Salvador Dalí's moustache is intact in the “10 past 10” position, the surrealist painter’s foundation has said, a day after his body was exhumed.

“It was like a miracle,” said Narcis Bardalet, who was in charge of embalming Dalí’s body twenty-eight years ago, adding that the hair was also intact.

The body was exhumed in the northeastern Spanish city of Figueres to settle a paternity case. A woman says her mother had an affair with the world-famous artist. If María Pilar Abel Martínez is proved right, she could assume part of Dalí’s estate, currently owned by the Spanish state.

Dalí’s body was exhumed from a crypt in a museum dedicated to his life and work on Thursday evening.

“When I took off the silk handkerchief, I was very emotional,” Mr. Bardalet told RAC1 radio station on Friday morning.

1817

1817

Portrait of Henry IV of France, by Santi di Tito, 1600. Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence.

In honor of the French Republic’s first anniversary in 1793, revolutionaries stormed the royal tombs at St. Dennis, exhuming and desecrating the Bourbon corpses. Expecting to find bodies marred by death and sin, the gravediggers instead confronted the immaculate remains of long-deceased kings. Henry IV of France’s condition was so impressive that the troop produced a death mask, which one academic cites as evidence of the 180-year-old corpse’s “lush beard and mustache.”

Two decades later English printer and publisher William Stevenson described the exhumation in his supplement to James Bentham’s History of the Church of Ely:

The corpse of Turenne (killed by a cannonball in 1675) was found in such a state of preservation as not to be in the least deformed, nor were the features of his countenance at all altered. Deprived of none of its freshness, and bearing a perfect resemblance to the portraits and medallions of that great general, this body was in the dry mummy state, of the color of bright bistre. On the same occasion, the body of Henry the Great, who died in 1610, appeared in the same perfect preservation. On opening the coffin of Louis XV, who died in 1774, the body of that prince, closely enveloped in swaddling clothes and fillets, was discovered quite whole, fresh, and well preserved: the skin was white, the nose of a violet color, and the buttocks red, like those of an infant newly born, floating in a liquor, composed of dissolved sea salt, with a preparation of which it had (to use the expression) been cured, not having been embalmed according to the usual method. As those personages were not particularly remarkable for the sanctity of their lives, we may infer that the seemingly supernatural appearances were the effect of the embalming art, and of no miraculous intervention.