2014

2014

As the people of Ukraine ousted their former President Viktor F. Yanukovych, residents of Kiev also spent the weekend attempting to discover what, precisely, Yanukovych had been hiding in his residential compound. In addition to covert documents detailing illegal money transfers and structures built to resemble Greek and Roman ruins, they also discovered the now-deposed leader’s private menagerie. The New York Times reports:

They saw about a half-dozen large residences of various styles, a private zoo with rare breeds of goats, a coop for pheasants from Asia, a golf course, a garage filled with classic cars and a private restaurant in the form of a pirate ship, with the name “Galleon” on the stern.

Autocrats seem to have a propensity for private zoos, and Mr. Yanukovych’s palace complex contained multiple enclosures for exotic animals. Rare pheasants with magnificent, iridescent red tails scratched about in their cages, nervous from the crowds walking past and snapping pictures. The labels on the cages identified them as “Diamond pheasant” and “Japanese long-tailed pheasant.”

Other cages held dogs, and there were pens for goats and what appeared to be rare breeds of pigs.

1794

1794

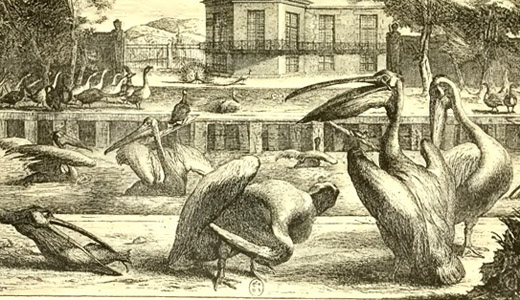

After the removal of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette from the palace of Versailles, the people of France were left wondering what to do with the family’s embarrassment of riches. The zoo, standard for any eighteenth-century royal, proved especially troublesome. Where could these animals, including a lion and a rhinoceros, be moved? Who would care for them? And in the age of libertié,égalitié, and fraternitié, could the taming of wild beasts truly be justified? Naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, after taking an inventory of all the creatures left at the Versailles menagerie, reflected on the keeping of animals in the new republic:

Until now, the most beautiful menageries were nothing but prisons where the cramped animals displayed the physiognomy of sadness, lost their fur, and remained permanently in positions that attested to their listlessness.

In bringing us close to all of the productions of nature, let us not make them prisoners. An author has said that our cabinets were tombs: well then! Let everything enjoy new life as a result of our attentions, and let the animals destined for our pleasure and for the instruction of the people no longer wear on their brows, as in the menageries built by the pomp of kings, the brand of slavery.