Up the stairs I ran to the wan mother and whimpering babe, to the sanctuary on whose altar a life at my bidding had offered itself to win a life, and won. What is this tiny formless thing, this newborn wail from an unknown world, all head and voice? I handle it curiously, and watch perplexed its winking, breathing, and sneezing. I did not love it then—it seemed a ludicrous thing to love—but her I loved, my girl-mother, she whom now I saw unfolding like the glory of the morning—the transfigured woman.

Through her I came to love the wee thing, as it grew and waxed strong, as its little soul unfolded itself in twitter and cry and half-formed word, and as its eyes caught the gleam and flash of life. How beautiful he was, with his olive-tinted flesh and dark-gold ringlets, his eyes of mingled blue and brown, his perfect little limbs, and the soft voluptuous roll which the blood of Africa had molded into his features! I held him in my arms, after we had sped far away to our Southern home—held him, and glanced at the hot red soil of Georgia and the breathless city of a hundred hills, and felt a vague unrest. Why was his hair tinted with gold? An evil omen was golden hair in my life. Why had not the brown of his eyes crushed out and killed the blue?—for brown were his father’s eyes, and his father’s father’s. And thus in the Land of the Color–line I saw, as it fell across my baby, the shadow of the Veil.

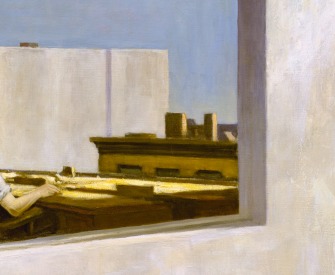

Within the Veil was he born, said I, and there within shall he live, a Negro and a Negro’s son. Holding in that little head—ah, bitterly!—the unbowed pride of a hunted race, clinging with that tiny dimpled hand—ah, wearily!—to a hope not hopeless but unhopeful, and seeing with those bright wondering eyes that peer into my soul a land whose freedom is to us a mockery and whose liberty a lie. I saw the shadow of the Veil as it passed over my baby; I saw the cold city towering above the blood-red land. I held my face beside his little cheek, showed him the star children and the twinkling lights as they began to flash, and stilled with an evensong the unvoiced terror of my life.

So sturdy and masterful he grew, so filled with bubbling life, so tremulous with the unspoken wisdom of a life but eighteen months distant from the All-life—we were not far from worshipping this revelation of the divine, my wife and I. Her own life built and molded itself upon the child; he tinged her every dream and idealized her every effort. No hands but hers must touch and garnish those little limbs; no dress or frill must touch them that had not wearied her fingers; no voice but hers could coax him off to dreamland, and she and he together spoke some soft and unknown tongue and in it held communion. I too mused above his little white bed; saw the strength of my own arm stretched onward through the ages through the newer strength of his; saw the dream of my black fathers stagger a step onward in the wild phantasm of the world, heard in his baby voice the voice of the Prophet that was to rise within the Veil.

Henri IV Playing with His Children, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1817. Petit Palais, Paris.

And so we dreamed and loved and planned by fall and winter, and the full flush of the long Southern spring, till the hot winds rolled from the fetid Gulf, till the roses shivered and the still stern sun quivered its awful light over the hills of Atlanta. And then one night the little feet pattered wearily to the wee white bed, and the tiny hands trembled; and a warm flushed face tossed on the pillow, and we knew baby was sick. Ten days he lay there, a swift week and three endless days, wasting, wasting away. Cheerily the mother nursed him the first days and laughed into the little eyes that smiled again. Tenderly then she hovered round him, till the smile fled away and fear crouched beside the little bed.

Then the day ended not, and night was a dreamless terror, and joy and sleep slipped away. I hear now that voice at midnight calling me from dull and dreamless trance, crying, “The Shadow of Death! The Shadow of Death!” Out into the starlight I crept, to rouse the gray physician—the Shadow of Death, the Shadow of Death. The hours trembled on; the night listened; the ghastly dawn glided like a tired thing across the lamplight. Then we two alone looked upon the child as he turned toward us with great eyes and stretched his stringlike hands—the Shadow of Death! And we spoke no word, and turned away.

He died at eventide, when the sun lay like a brooding sorrow above the western hills, veiling its face; when the winds spoke not, and the trees, the great green trees he loved, stood motionless. I saw his breath beat quicker and quicker, pause, and then his little soul leapt like a star that travels in the night and left a world of darkness in its train. The day changed not; the same tall trees peeped in at the windows, the same green grass glinted in the setting sun. Only in the chamber of death writhed the world’s most piteous thing—a childless mother.

Blithe was the morning of his burial, with bird and song and sweet-smelling flowers. The trees whispered to the grass, but the children sat with hushed faces. And yet it seemed a ghostly unreal day—the wraith of life. We seemed to rumble down an unknown street behind a little white bundle of posies, with the shadow of a song in our ears. The busy city dinned about us; they did not say much, those palefaced hurrying men and women; they did not say much—they only glanced and said, “Niggers.”

All that day and all that night there sat an awful gladness in my heart—nay, blame me not if I see the world thus darkly through the Veil—and my soul whispers ever to me, saying, “Not dead, not dead, but escaped; not bound, but free.” No bitter meanness now shall sicken his baby heart till it die a living death, no taunt shall madden his happy boyhood. Fool that I was to think or wish that this little soul should grow choked and deformed within the Veil! I might have known that yonder deep unworldly look that ever and anon floated past his eyes was peering far beyond this narrow now. In the poise of his little curl-crowned head did there not sit all that wild pride of being which his father had hardly crushed in his own heart? For what, forsooth, shall a Negro want with pride amid the studied humiliations of fifty million fellows? Well sped, my boy, before the world had dubbed your ambition insolence, had held your ideals unattainable, and taught you to cringe and bow. Better far this nameless void that stops my life than a sea of sorrow for you.

From The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois studied with William James at Harvard University, receiving his PhD in 1895 and publishing his dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, the following year. Helping to form the NAACP in 1909, he became the organization’s director of research and the founding editor of its magazine, The Crisis, where he served for twenty-four years, publishing the writing of, among others, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, and Countee Cullen.

Back to Issue