There are truths that prove their discoverers witless.

—Karl Kraus, 1909Column Opinion

Vitruvius looks to the natural world.

Three sorts of columns, different in form, have received the appellations of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, of which the first is of the greatest antiquity. For Dorus, the son of Hellen and the nymph Orseis, reigned over the whole of Achaea and Peloponnese and built at Argos, an ancient city on a spot sacred to Juno, a temple that happened to be of this order. After this, many temples similar to it sprung up in the other parts of Achaea, though the proportions that should be preserved in it were not as yet settled.

But afterward, when the Athenians sent over into Asia thirteen colonies, the chief commander was Ion, who led them over into Asia, occupied the borders of Caria, and there built great cities. Allotting different spots for sacred purposes, the Athenians began to erect temples, the first of which was dedicated to Apollo Panionios and resembled that which they had seen in Achaea, and they gave it the name of Doric because they had first seen that species in the cities of Doria.

As they wished to erect this temple with columns and had not a knowledge of the proper proportions of them, nor knew the way in which they ought to be constructed, so as at the same time to be both fit to carry the superincumbent weight and to produce a beautiful effect, they measured a man’s foot, and finding its length the sixth part of his height, they gave the column a similar proportion, that is, they made its height, including the capital, six times the thickness of the shaft measured at the base. Thus the Doric order obtained its proportion, its strength, and its beauty, from the human figure.

With a similar feeling, they afterward built the temple of Diana. But in that, seeking a new proportion, they used the female figure as the standard; and for the purpose of producing a more lofty effect, they first made it eight times its thickness in height. Under it they placed a base, after the manner of a shoe to the foot; they also added volutes to its capital, like graceful curling hair hanging on each side, and the front they ornamented with cymatia and festoons in the place of hair. On the shafts they sunk channels that bear a resemblance to the folds of a matronly garment. Thus two orders were invented, one of a masculine character, without ornament, the other bearing a character that resembled the delicacy, ornament, and proportion of a female.

The successors of these people, improving in taste and preferring a more slender proportion, assigned seven diameters to the height of the Doric column, and eight and a half to the Ionic. That species, of which the Ionians were the inventors, has received the appellation of Ionic. The third species, which is called Corinthian, resembles in its character the graceful, elegant appearance of a virgin in whom from her tender age the limbs are of a more delicate form and whose ornaments should be unobtrusive.

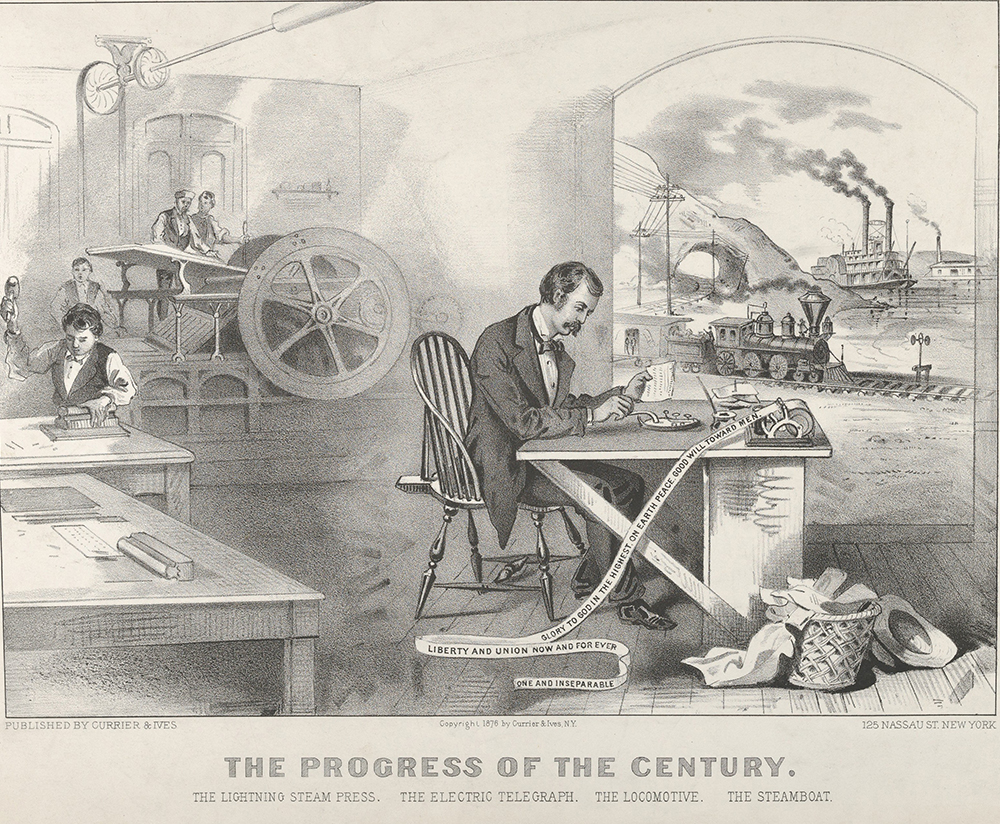

The Progress of the Century—The Lightning Steam Press, the Electric Telegraph, the Locomotive, the Steamboat, by Currier and Ives, 1876. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Adele S. Colgate, 1962.

The invention of the capital of this order is said to be founded on the following occurrence. A Corinthian virgin of marriageable age fell victim to a violent disorder. After her interment, her nurse, collecting in a basket those articles to which she had shown a partiality when alive, carried them to her tomb and placed a tile on the basket for the longer preservation of its contents. The basket was accidentally placed on the root of an acanthus plant, which, pressed by the weight, shot forth toward spring its stems and large foliage and, in the course of its growth, reached the angles of the tile, and thus formed volutes at the extremities.

Callimachus, who, for his great ingenuity and taste was called by the Athenians Catatechnos, happening at this time to pass by the tomb, observed the basket and the delicacy of the foliage that surrounded it. Pleased with the form and novelty of the combination, he constructed from the hint thus afforded columns of this species in the country about Corinth and arranged its proportions, determining their proper measures by perfect rules.

Vitruvius

From On Architecture. In book three of his ten-volume treatise, Vitruvius articulates the close relationship between human and architectural forms. “It was from the members of the body,” he writes, that the gods “derived the fundamental ideas of the measures that are obviously necessary in all works.” Leonardo da Vinci later based his “Vitruvian Man” on the Roman architect’s detailed descriptions. Little is known of Vitruvius outside of his work, throughout which he establishes himself as a Hellenist who disdained contemporary Roman architectural fashions.