In early youth, as we contemplate our coming life, we are like children in a theater before the curtain is raised, sitting there in high spirits and eagerly waiting for the play to begin. It is a blessing that we do not know what is really going to happen. Could we foresee it, there are times when children might seem like innocent prisoners, condemned not to death, but to life, and as yet all unconscious of what their sentence means. Nevertheless every man desires to reach old age; in other words, a state of life of which it may be said, “It is bad today, and it will be worse tomorrow—and so on till the worst of all.”

If you try to imagine as nearly as you can what an amount of misery, pain, and suffering of every kind the sun shines upon in its course, you will admit that it would be much better if on the earth as little as on the moon the sun were able to call forth the phenomena of life; and if, here as there, the surface were still in a crystalline state.

Again, you may look upon life as an unprofitable episode, disturbing the blessed calm of nonexistence. And in any case, even though things have gone with you tolerably well, the longer you live the more clearly you will feel that, on the whole, life is a disappointment, nay, a cheat.

If two men who were friends in their youth meet again when they are old, after being separated for a lifetime, the chief feeling they will have at the sight of each other will be one of complete disappointment at life as a whole; because their thoughts will be carried back to that earlier time when life seemed so fair as it lay spread out before them in the rosy light of dawn, promised so much—and then performed so little. This feeling will so completely predominate over every other that they will not even consider it necessary to give it words; but on either side it will be silently assumed, and form the groundwork of all they have to talk about.

He who lives to see two or three generations is like a man who sits some time in the conjurer’s booth at a fair and witnesses the performance twice or thrice in succession. The tricks were meant to be seen only once, and when they are no longer a novelty and cease to deceive, their effect is gone.

If children were brought into the world by an act of pure reason alone, would the human race continue to exist? Would not a man rather have so much sympathy with the coming generation as to spare it the burden of existence? Or at any rate not take it upon himself to impose that burden upon it in cold blood.

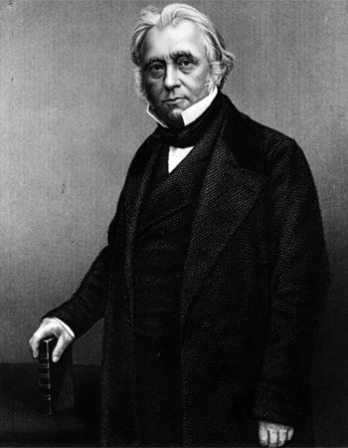

From Studies in Pessimism. Often referred to as the “philosopher of pessimism,” Schopenhauer rejected G. W. F. Hegel’s belief in the progressive nature of history, calling him a “pitiful charlatan” and stating that “the continuous and perpetual existence of the human race is merely proof of its exuberance and wantonness.” He published his masterwork, The World as Will and Representation, in 1819 and the following year delivered lectures at the University of Berlin, purposefully giving them at the same time as Hegel gave his.

Back to Issue