Guard more faithfully the secret which is confided to you than the money which is entrusted to your care.

—Isocrates, 370 BCRise of the Drones

Drone technology spans a century’s worth of science fiction and military research.

By Rudolph Herzog

Boeing B-17F radar bombing through clouds over Bremen, Germany, on November 13, 1943. United States Air Force.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

When the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, there were only a handful of aerial drones in its invasion force. By 2010 the Pentagon had nearly 7,500 drones in its arsenal. Today almost one in three U.S. military aircraft does not have a pilot. This technological revolution has been driven by the use of weaponized American drones, especially the Predator and Reaper. To illustrate the impact of these new weapons: drone campaigns in Pakistan, a country not at war with the U.S., have killed more people than died in the entire NATO-led war on Yugoslavia in 1999.

Despite the futuristic concept of robotic air warfare, drone technology goes back a hundred years. The technological groundwork was first established by genius inventor Nikola Tesla, who introduced radio-control technology at Madison Square Garden in 1898. Tesla immediately realized his invention’s military potential, noting that the technology would allow man to build devastating remote weapons that would be a deterrent so inhuman and destructive that, in his imagination, they would “lead to permanent peace between the nations.”

Driven by the same fin-de-siècle enthusiasm, Archibald Montgomery Low, a British engineer, recognized the potential of marrying airplanes with wireless transmission. At the beginning of World War I, he won a commission to build a remotely piloted weapon to destroy German Zeppelins. He experimented with numerous designs but had little success, crashing various prototypes. While Low was able to demonstrate that planes could be steered with Tesla’s radio waves, his anti-airship weapon never got close to production. Since the devices were designed to self-destruct, the concept was in most ways closer to modern rockets or cruise missiles. Nevertheless, Low’s machines can be seen as the earliest precursors of combat drones.

A continent away, another inventor was also working to keep unpiloted aircraft safely airborne. Once described as “the epitome of the Yankee inventor,” Elmer Sperry had widespread interests that ranged from recycling tin from scrap metal to developing searchlights for the U.S. Navy. Fascinated by the idea of remotely steered and even fully autonomous planes, he realized the need for an effective stabilizing mechanism. Supported by the navy, Sperry started experimenting with gyroscopes. First tests showed promise in 1915, and Sperry joined forces with engineer Peter Cooper Hewitt to develop an “aerial torpedo,” a small pilotless aircraft filled with explosives. Less than a year later they were ready to demonstrate a prototype to T.S. Wilkinson of the navy’s Bureau of Ordnance. The machine consisted of a winged frame that was launched by catapult. Aided by a precision barometer, it climbed to a prescribed height. Once it had reached its final altitude, a mechanical counter calculated how far the aerial torpedo had to fly to reach its target. The device could then be set to drop a bomb or crash and explode on impact. While the advantages of not putting pilots’ lives at risk during missions must have been apparent, the navy was not impressed with the accuracy of Sperry’s invention. But as the U.S. was about to join World War I, Sperry was able to convince the U.S. government to sink several thousand dollars into developing a system that could fly by autopilot or be steered by radio control. The navy saw its potential in assaults on heavily guarded submarine bases like the German base at Helgoland Island. Sperry set up camp at a flying field in Copiague, New York, but his project to build drones soon ran into significant trouble. One problem was the launching device. Catapults and railroad tracks were used, but both proved to be problematic. Difficulties with getting the machines airborne obscured another complication: the aerodynamic quality of the airframe was inadequate. After several botched launches, Sperry realized he had to pay more attention to the plane’s design. He had a prototype based on the hydroplane Curtiss N-9H fitted with a pilot’s seat and a stick control. In a dangerous act of brinkmanship, the inventor’s son tested the configuration. During the first takeoff, Lawrence Sperry flipped the airframe and wrecked it. Miraculously, he survived the crash unhurt and volunteered for a second attempt. He managed to get a substitute frame airborne, but when he switched to autopilot it banked and flipped twice. He managed to wrest back the controls from the machine, leveling it out and landing without injury. Yet despite Sperry’s mixture of ingenuity and derring-do, his project mainly ended up swallowing sizable amounts of money. There was, however, one moment of triumph. On March 6, 1918, one of Sperry’s drones flew as programmed exactly three thousand feet, and neatly descended into the water. It was the first autopiloted flight on record, though attempts to replicate the successful test failed.

While the aerial torpedo never came close to contributing to the war effort, a rival system almost saw frontline use. The U.S. Air Force, too, had become interested in drone technology. It tapped Charles Kettering to build a winged autonomous vehicle armed with a warhead, what would later be known as the “Kettering Bug.” Early prototypes of the device were made out of a material like papier mâché, later ones out of wood. Like Sperry’s machines, they were stabilized by a gyroscope. The autopilot consisted of flight instruments rigged to cranks and bellows gutted from a player piano. The gadget could cast off its wings to swoop down on a target. The project also recruited engineers Elmer Sperry and Orville Wright.

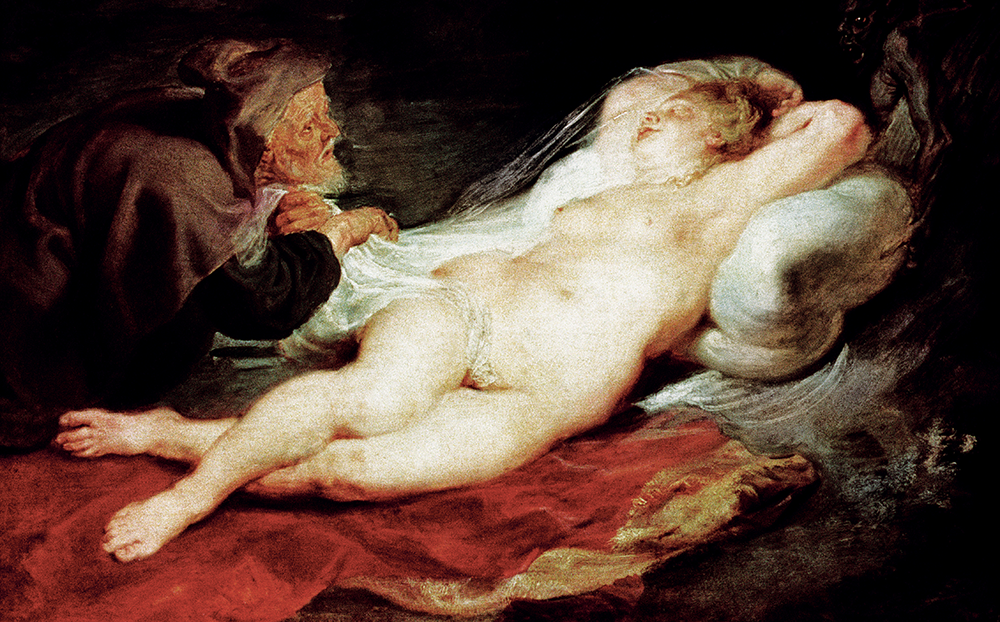

The Hermit and Sleeping Angelica, by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1628. © Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna / Bridgeman Images.

As the tests proceeded, the Air Force realized that its engineers lacked a solution to the problems that had stymied the development of the aerial torpedo. During a demonstration, Kettering’s team escaped a catastrophe when the bug spun out of control and narrowly missed the reviewing stands. After fixing the problems that had destabilized the prototypes, the engineers finally felt confident enough to ship out a batch of drones to the front line. Kettering sent one of his best men, Henry “Hap” Arnold, to Europe to convince leaders of the use of the bug. But Arnold had barely embarked on his trip before catching the Spanish Flu, which incapacitated him for a month. Just after his late arrival at the Western Front, the armistice went into effect. The Kettering Bug never flew a single mission.

After the war, development on Sperry’s aerial torpedo continued for some time, then eventually petered out. Film footage documents the manifold challenges that hampered its progress. Only one of the dozen or so launches was successful, with the grainy footage showing the drone bobbing through the air, kept in precarious equilibrium. Ultimately, the technology had proved too ambitious for its era.

That unmanned aerial vehicles re-entered the arsenal of the U.S. military is to a large part due to the ingenuity of an unlikely arms manufacturer: British actor Reginald Denny, one of the stars of Hollywood’s silent era. With a pencil mustache, a wide grin, and an angular physique, he appeared in light comedies, typecast as a jolly but slightly dimwitted Brit. A former member of the World War I Royal Flying Corps, Denny was an airplane enthusiast who became intensely interested in toy airplanes. His interest in these toys developed, as he later told the story, from a chance encounter with a boy trying to get his toy plane airborne. Offering to help, Denny accidentally crashed and wrecked it. Shopping around for a suitable replacement for the boy, the actor became hooked on flying model aircraft.

In the 1930s toy planes were made from balsa wood and commonly powered by rubber bands, and they didn’t fly particularly far. Denny started tinkering and became intrigued by the technology, which was shared by fellow actors Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda. Denny even set up his outfit, the Denny Radioplane Company. From a shop on Hollywood Boulevard he sold models that looked like scaled-down planes. More upmarket models were powered by a miniature engine, designed by engineer Walter Righter, from whom Denny had acquired patent rights. Eventually, the actor hit upon the idea of manufacturing radio-controlled model aircraft that could be used as targets to train antiaircraft gunners. He proposed the idea to the U.S. military but received a lukewarm response. Yet with the start of World War II, he was asked to mass-produce these drones. In the following years, Denny’s company morphed into a million-dollar business, turning out thousands of flying targets. Launched by a catapult, these drones were remote-controlled by an operator who steered them into the range of antiaircraft guns. They had one feature that was completely new: since they were rigged to a parachute, they were reusable. For this reason, the Denny radioplane OQ 2 was the first mass-produced unmanned aerial vehicle in the sense that we know it today. All other similar devices, until then, were built to self-destruct. As the radioplane company blossomed, it hired more staff. Since men were being drafted to fight, women were hired to work on the production line. In 1944 Norma Jean Dougherty, the future Marilyn Monroe, started doing shifts at the Denny site near the Burbank airport. As it happened, a photographer for the Army magazine Yank was sent to the radio-plane factory, dispatched by his commanding officer, Ronald Reagan. The photographer spotted Dougherty and asked her to pose with the propeller of a drone. He soon persuaded her to model for more photographs, the first stop to her career as an actress.

A separate World War II–era drone program was driven by grave threats emerging from Nazi Germany. As early as mid-1940, Nazi engineers had started developing long-range artillery weapons so novel and secret that they were only referred to as Vergeltungswaffen, or reprisal weapons. The sites where these munitions were built were heavily guarded and assaulting them with bombers came at a deadly risk. Sometime in September 1943, aerial photographs reached Allied High Command showing the Nazis had begun building an elaborate structure near the hamlet of Mimoyecques in the Pas-de-Calais. More than one thousand workers, many of them prisoners, were involved in excavating a labyrinthine system of tunnels. Above ground, military trucks arrived, delivering mysterious pipes and metal rails. Allied analysts concluded that the site was designated as a launching site for the V1 rocket. In fact, the device was something even more devastating. Code-named Fleissiges Lieschen, or Busy Lizzie, it was to be the world’s most powerful supergun, designed to shell London with an incessant barrage of explosives. Instead of sending bombers to the British capital, Hitler planned to pummel the city with hundreds of rounds per hour.

Detective Allan Pinkerton and President Abraham Lincoln, Battle of Antietam, 1862. Photograph by Alexander Gardner. © The Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman Images.

After more than a dozen attacks on the site, the Allies had suffered such heavy losses that they decided to deploy a revolutionary new weapon. Project Anvil promised to accomplish something seemingly impossible: kamikaze attacks on the enemy without the loss of a pilot. The concept involved gutting battle-fatigued PB4Y-1 Liberator and Fortress bombers and furnishing them with a system of pulleys and motors that allowed a crew flying in an accompanying plane to pilot them remotely with a radio linkup. The most innovative element of these drones, though, was a television camera that relayed live images from the nose cone to operators in the chaser plane. Television was a new invention, not yet widely available in the consumer market. Cameras in Project Anvil were used to guide the way to enemy targets where the behemoths were made to crash, causing tons of Torpex, a high explosive stacked in their bellies, to detonate. Despite their lethal potential, the unmanned flying machines had one drawback: they could not take off on their own. Pilots were required inside the crafts to get them airborne and on course. Once they had been pointed in the direction of their target, the pilots would activate the remote steering system and bail out by parachute. In the case of the bombing of Mimoyecques, the U.S. Navy selected a man who was uniquely suited for this task. Born in 1915, Joseph “Joe” Kennedy was the older brother of John F. Kennedy. He volunteered for hazardous missions in Britain, helping to clear the North Sea of German submarines. Though he qualified for leave, he volunteered to take part in the drone attack on the Nazi supergun site. On August 12, 1944, Kennedy and experienced weapons officer Wilford John Willy boarded a liberator drone and taxied the aircraft out on the runway. The hold was loaded with a deadly cargo of 10.6 tons of Torpex. As they took off, eight airplanes joined them: four were armed Mustangs, a security detail, two Mosquitos carrying observers, and a further two Venturas, each fitted with a set of remote controls to pilot the drone in case one of the devices failed. As they approached the British coast, lieutenant Willy started arming the charges. He also activated the “block,” the code name for the television camera. Once he had completed his round, both pilots readied themselves to bail out. Kennedy pulled up the drone to an altitude of 600 meters. When the plane had reached its prescribed altitude, he radioed “zoot suit,” code that all was ready. Two minutes later the drone exploded. The blast was so powerful that the debris was scattered across an area spanning more than two miles. Most parts rained down on New Delight Wood, a dense English forest that immediately caught fire. The flames caused damage to 147 properties. Kennedy and his copilot were killed instantly. The most likely reason for the crash, experts concluded, was that an electronic pulse from the TV camera unit triggered the fuse of one of the charges. Whatever the cause, Project Anvil was suspended.

A rival U.S. program in the Pacific proved to be more successful. The navy commissioned the Interstate Aircraft and Engineering Corporation plant to build a line of assault drones under the condition that they be manufactured with almost no war-critical components. Instead of metal, the fuselage and wings of these devices were crafted out of wood hardened and bent by experts at the Wurlitzer Musical Instrument Company. While the materials used made the Torpedo Drone TDR-1 appear rather quaint, its inner workings were state of the art, including radio control, a TV camera, and a radar-tracking device. “The main thing that was impressed on all of us,” one of the operators later recalled, “was that this was top secret. We were not allowed to discuss it, even among ourselves.” Posted in the Russell Islands, the unit soon began attacks on Japanese antiaircraft sites. Launched by a ground crew, the TDR-1s were turned over to a control pilot with a joystick who crouched under a blanket in a TBM chaser plane, staring at the sickly green images relayed to him by the drone’s camera. This operator would then guide the armed, unmanned aircraft into the target while the TBM hovered at a safe distance from the enemy’s flak. The task force soon scored hits against grounded ships on the water that served as outposts for Japanese antiaircraft guns. Objects like these that were clearly silhouetted against the sky proved to be the best targets. Finding camouflaged targets against the backdrop of the jungle on a monochrome TV screen, however, was a different matter. Despite these challenges, TDR-1’s wartime record proved to be satisfactory, with the unit making twenty-one direct hits on targets. More important, no American was killed during these raids, underscoring the potential of the weapon.

With the advent of long-range bombers and ballistic missiles, military planners lost interest in armed drones. While the military’s appetite for drones was waning, popular culture was flooded with killer machines. In the 1953 film Robot Monster, an android attempts to annihilate the last living family on earth.

In Target Earth (1954) robots from Venus invade planet Earth, and in Kronos (1957) aliens send a gigantic robot to earth to suck dry its energy supply. At the same time moviegoers indulged in these apocalyptic fantasies, one man was putting serious thought into the question of what would happen if the rise of the machines ever became reality. The science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov, who coined the terms robotics and positronic in 1942 published a short story that contained Three Laws of Robotics, which can be read as the first reflection on the ethics of robotic weapons. Asimov’s first law is that a robot may never injure a human; the second, that it must obey humans unless this interferes with the first law; the third, that a robot must protect its own existence, as long as such protection does not conflict with the other laws. Asimov’s laws for robots are still referenced today. While some argue that latter-day drones are not robots since they are remotely piloted and can neither think nor act autonomously, developments in drone technology are taking place so rapidly that Asimov’s laws may soon be of practical use.

We must not always talk in the marketplace of what happens to us in the forest.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1850Though 1950s technology could not come close to what was being imagined by filmmakers and writers of pulp fiction, this changed in the early 1960s, following several shoot-downs of U2 and B-47 spy planes by the Soviets. These events made the U.S. military and the CIA realize its manned reconnaissance missions were increasingly risky. The Soviet Union’s antiaircraft missile defense had upgraded so substantially that it had become unsafe to breach its airspace. So the United States dramatically accelerated the development of new drones, culminating in the Lightning Bug, a UAV that was fitted to sniff out Soviet nuclear-missile sites. The Vietnam War saw the first large-scale use of drones in combat, with, on average, one mission flown each day. Meanwhile, the navy experimented with a helicopter drone, the DASH QH-50, which was sent to Vietnam to spot artillery targets and hunt submarines. A configuration was imagined that would have allowed the drone to deliver a tactical nuclear bomb, though deployment was never attempted. During its first few decades of service the drone proved to be a capricious piece of equipment, with 441 of them lost, mostly due to technical failure.

As the Cold War heated up, spying missions became more ambitious, culminating in the development of supersonic reconnaissance drones. The most enigmatic of these machines was the gargantuan Soviet Tupolev Tu-123, a modified cruise missile bristling with cameras and electronic sniffers. This system was especially expensive since it was not reusable and had to be ditched after every sortie. To this day, it is unknown what scouting missions were conducted with the craft and it is lucky that it was never detected, since the West’s early warning line would almost certainly have interpreted its frame and flight pattern as being that of an inbound Soviet nuclear missile.

Thirty years later drones have become ubiquitous. This is due to advancements made by Israeli engineer Abraham Karem, who invented the durable airframe that was to become the feared Predator. His updated drones met an emerging, insatiable demand. Proponents of drone technology, especially the U.S. and Israel, see themselves under threat of “asymmetric” incursions, especially terrorist attacks. In such conflicts, gathering intelligence in real time is considered just as crucial as the military might of tanks and cannons. Meanwhile global positioning systems, developed as a military technology in the 1970s, have made drones considerably more accurate. With a network of satellite relay stations like the U.S. base in Ramstein, Germany, drones can be piloted from bases halfway across the globe. High-resolution video cameras and new signals-intelligence technology have also increased drone capabilities, with drones able to track and target individual cell phones even after they have been turned off and the battery removed. Today, military drones both eavesdrop on everything from phone conversations to emails and perform “hunter-killer” missions.

While the public is grappling with the ethical implications of remotely piloted drone campaigns, new challenges loom on the horizon. As the technology advances, drones will likely become increasingly autonomous. Even the decision to kill may be delegated to robots, something recently condemned as “death by algorithm” by a UN Special Rapporteur. As nations aside from the U.S. acquire and deploy drones, there is also the possibility of aerial combat between fighter drones flying at incredible speeds, requiring maneuvers at such speed that a human pilot is simply too slow to respond.

Mata Hari, 1905. Photograph by Reutlinger Studio. © Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris / Archives Charmet / Bridgeman Images.

The American Reapers and Predators have proved to be far from the precision weapons they were once made out to be. Civilian deaths in Pakistan and Afghanistan are substantial. According to a recently leaked cache of government files, 90 percent of fatalities in one U.S. operation in Afghanistan over a five-month period in 2012 and 2013 were other than the intended targets. According to the leaked documents, targets are referred to as “objectives” and kills as “jackpots”; people killed other than the designated target are referred to as “EKIA,” enemy killed in action, even if no connection to the target is established.

A study by a Pentagon task force complains that in ongoing U.S. campaigns in Yemen and Somalia, drones, limited by fuel and available bases, sometimes spend half their time in transit to surveillance targets, making the drone war expensive and inefficient. This is summarized by the authors of the report as a cause of the “tyranny of distance” that results from waging war from remote bases. An additional complaint is that though drones can hover above an enemy—capturing electronic communications, tracking the movement of a target—enemies are becoming more elusive. An army with troops on the ground can interrogate captured combatants and collect human intelligence. Pursuing an enemy purely from the air, however, gives commanders little of what is really going on.