When a man dies, and his kin are glad of it, they say, “He is better off.”

—Edgar Watson Howe, 1911Last Meals

The choice of the final meal contains a curious paradox: why mark the end of a life with the stuff that fuels it?

By Brent Cunningham

The Afternoon Meal (La Merienda), by Luis Meléndez, c. 1772. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

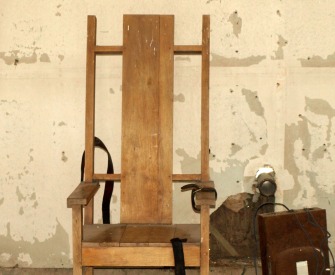

In January 1985, Pizza Hut aired a commercial in South Carolina that featured a condemned prisoner ordering delivery for his last meal. Two weeks earlier, the state had carried out its first execution in twenty-two years, electrocuting a man named Joseph Carl Shaw. Shaw’s last-meal request had been pizza, although not from Pizza Hut. Complaints came quickly; the spot was pulled, and a company official claimed the ad was never intended to run in South Carolina.

It’s not hard to understand why Pizza Hut’s creative team thought the ad was a good idea. The last meal offers an irresistible blend of food, death, and crime that drives a commercial and voyeuristic cottage industry. Studiofeast, an invitation-only supper club in New York City, hosts an annual event based on the best responses to the question, “You’re about to die, what’s your last meal?” There are books and magazine articles and art projects that address, among other things, what celebrity chefs—like Mario Batali and Marcus Samuelsson—would have for their last meals, or what the famous and the infamous ate before dying. Newspapers reported that Saddam Hussein was offered but refused chicken, while Esquire published an article about the terminally ill François Mitterrand, the former French president, who had Marennes oysters, foie gras, and, the pièce de résistance, two ortolan songbirds. The bird is thought to represent the French soul and, because it’s protected, is illegal to consume.

While the number of yearly executions in the United States has generally declined since a high of ninety-eight in 1999, the website Dead Man Eating tracked and commented on last-meal requests of death-row inmates across the country during the first decade of the new millennium. One of the site’s last posts, in January 2010, was the request of Bobby Wayne Woods, who was executed in Texas for raping and killing an eleven-year-old girl: “Two chicken-fried steaks, two fried chicken breasts, three fried pork chops, two hamburgers with lettuce, tomato, onion, and salad dressing, four slices of bread, half a pound of fried potatoes with onion, half a pound of onion rings with ketchup, half a pan of chocolate cake with icing, and two pitchers of milk.”

Film still from Looking for Alfred, directed by Johan Grimonprez, 2005. © Courtesy of zap-o-matik/Film & Video Umbrella/Sean Kelly Gallery.

There are also efforts to leverage the pop-culture spectacle of last meals to protest the death penalty. An Oregon artist has vowed to paint images of fifty last-meal requests of U.S. inmates on ceramic plates every year until the death penalty is outlawed. Amnesty International launched an anti–capital punishment campaign this past February that featured depictions of the last meals of prisoners who were later exonerated of their crimes.

No matter your stance on capital punishment, eating and dying are universal and densely symbolic human processes. Death eludes the living, and we are drawn to anything that offers the possibility of glimpsing the undiscovered country. If, as the French epicure Anthelme Brillat-Savarin suggested, we are what we eat, then a final meal would seem to be the ultimate self-expression. There is added titillation when that expression comes from the likes of Timothy McVeigh (two pints of mint-chocolate-chip ice cream) or Ted Bundy (who declined a special meal and was served steak, eggs, hash browns, toast, milk, coffee, juice, butter, and jelly). And when this combination of factors is set against America’s already fraught relationship with food, supersized or slow, and with weight and weight loss, it’s almost surprising that Pizza Hut didn’t have a winner on its hands.

The idea of a meal before an execution is compassionate or perverse, depending on your perspective, but it contains an inherently curious paradox: marking the end of a life with the stuff that sustains it seems at once laden with meaning and beside the point. As Barry Lee Fairchild, who was executed by the state of Arkansas in 1995, said in regard to his last meal, “It’s just like putting gas in a car that don’t have no motor.”

On January 14, 1772, in Frankfurt am Main, Susanna Margarethe Brandt prepared for her execution—she had killed her infant daughter—by sitting down to a sprawling feast with six local officials and judges. The ritual was known as the Hangman’s Meal. On the menu that day were “three pounds of fried sausages, ten pounds of beef, six pounds of baked carp, twelve pounds of larded roast veal, soup, cabbage, bread, a sweet, and eight and a half measures of 1748 wine.” Had she committed the crime in neighboring Bavaria, Brandt likely would have preceded the meal with a morning drink in her cell with the man who would later decapitate her with a sword. This shared aperitif was called St. John’s Blessing, after John the Baptist, who is said to have forgiven those who were about to behead him.

Brandt, who was twenty-five years old and is supposed to have inspired Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s character Gretchen in Faust, reportedly managed nothing more than a glass of water. Her companions in the repast fared little better.

The origins of the last-meal ritual aren’t settled. Although the earliest record of the death penalty is the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu in the twenty-second century BC, some scholars suggest the last meal may have begun in ancient Greece, and in Rome gladiators were fed a sumptuous last meal, the coena libera, the night before their date in the Colosseum. In eighteenth-century London, favored or better-off prisoners were allowed a party with food and drink and outside guests on the night before they were hanged. The next day, as the prisoner traveled the three miles from Newgate Prison to the gallows at Tyburn Fair, the procession would stop at a pub for the condemned’s customary “great bowl of ale to drink at their pleasure, as their last refreshment in life.” (England’s noble or high-born criminals, such as Anne Boleyn and the earl of Essex, were beheaded elsewhere, often at the Tower of London; Walter Raleigh reportedly took a last smoke from his tobacco pipe before he lost his head in Old Palace Yard at Westminster.) In the New World, the Aztecs feasted some of those who were tapped for ritual sacrifice, as part of a pre-execution deification ceremony that could last up to a year. Typically, these were warriors captured on the battlefield, and in some cases, after they were killed, their captor was given much of the body for use in tlacatlolli, a special stew of corn and human flesh that was served at a banquet with the captor’s family.

Today, most countries that use the death penalty as part of their criminal-justice systems offer some sort of last meal. Along with the United States, Japan and South Korea are the only industrialized democracies among the fifty-eight countries in the world that employ capital punishment, and in Japan, the condemned don’t know when they will be executed until the day arrives. In the 2005 documentary Last Supper, by the Swedish artists Mats Bigert and Lars Bergström, Sakae Menda, who spent thirty-four years on death row in Japan, said inmates may request whatever they want; if no request is made, prison officials provide “cakes, cigarettes, and drink.” Duma Kumalo, who spent three years awaiting death in South Africa, told the filmmakers that he was served a whole deboned chicken and given seven rand—about six dollars—to purchase whatever else he wanted. “What we bought before execution, it was not things that we wanted to eat,” said Kumalo, who was spared for reasons he does not explain, just hours before he was to be killed. “Those were the things which we were going to leave behind with those who would remain. Because people were starving.”

In America, where the death rows—like the prisons generally—are largely filled with men from the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder, last-meal requests are dominated by the country’s mass-market comfort foods: fries, soda, fried chicken, pie. Sprinkled in this mix is a lot of what social scientists call “status foods”—steak, lobster, shrimp—the kinds of foods that in popular culture conjure up the image of affluence. Every once in a while, though, a request harkens back to what, in the Judeo-Christian West, is the original last meal—the Last Supper, when Jesus Christ, foreseeing his death on the cross, dined one final time with his disciples. Jonathan Wayne Nobles, who was executed in Texas in 1998 for stabbing to death two young women, requested the Eucharist sacrament. Nobles had converted to Catholicism while incarcerated, becoming a lay member of the clergy, and made what was by all accounts a sincere and extended show of remorse while strapped to the gurney. He sang “Silent Night” as the chemicals were released into his veins.

The musician Steve Earle, whom Nobles asked to be among his witnesses at the execution, wrote of the experience in Tikkun magazine, “I do know that Jonathan Nobles changed profoundly while he was in prison. I know that the lives of other people with whom he came in contact changed as well, including mine. Our criminal justice system isn’t known for rehabilitation. I’m not sure that, as a society, we are even interested in that concept anymore. The problem is that most people who go to prison get out one day and walk among us. Given as many people as we lock up, we better learn to rehabilitate someone. I believe Jon might have been able to teach us how. Now we’ll never know.”

As of June of this year, governing bodies in the U.S. and its colonial predecessors had executed some 15,825 men and women since the first permanent European settlements were established. The majority of them, it seems, did not get a special last meal; the Newgate Prison parties didn’t make the crossing with William Bradford and John Carver aboard the Mayflower. There is no record of a last meal for George Kendall, believed to be the first Englishman executed in the New World, who was accused of spying for Spain and shot in Jamestown in 1608. (The nature of criminal justice around that time was such that Kendall would also have been shot—or hanged, beheaded, or burned at the stake—for stealing grapes.)

Scott Christianson, who has written extensively on the history of American prison culture, believes the standardized last meal probably emerged around the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth, with the rise of a modern administrative state. Messy and raucous public executions fell out of favor with the more refined sensibilities of the upper and middle classes, and ideas of man’s ability for moral improvement fueled opposition to the death penalty. Rehabilitation, rather than simply deterrence and retribution, became an important aim of criminal sanction. At the same time, though, there was still a strong fear of social disorder; the assertive state governments were eager to find better ways to keep the peace in a fledgling nation whose cities were growing, industrializing, and diversifying.

Ascent into the Empyrean (detail), by Hieronymus Bosch, 1500-1504. Palazzo Grimani, Venice.

The answer, or so it seemed, was to replace the more communal sanctions of the colonial and early republic era—fines, banishment, floggings, labor—with long-term incarceration in state-run penitentiaries. Criminals would be isolated from society and purged of their deviant impulses. Executions, which had long been believed to have a scared-straight effect on the public, were now thought to inspire the very violence they were meant to deter. They moved to yards inside the prisons, where the witnesses were only a select few, usually prominent officials and merchants.

In addition to efficiency and decorum, Christianson writes, another “new aspect of this choreographed ritual of death entailed the release of detailed reports to the public that described,” among other things, “precisely what the condemned had requested as his or her last meal.” This gave the impression of a humane and dispassionate custodial government authority, but it also—intentionally or not—tapped into a bit of the old public fascination with executions, when a family might hop in the wagon, ride to the town square with a picnic basket in tow, and watch someone be “launched into eternity.”

The press, Christianson says, “ate it up.” This was the dawning of the penny press, when steam-driven printing presses spurred the development of a mass media in America. As executions vanished inside penitentiaries, newspapers discovered that the public was still eager for accounts of the proceedings. In 1835, for instance, readers of New York’s Sun and Herald newspapers learned that Manual Fernandez, among the first men at Bellevue Prison to be privately executed, enjoyed cigars and brandy on his last day, compliments of the warden.

Nearly two hundred years later, America is in the grips of a revolution in communication technology even more pervasive than the penny press. The death penalty was resurrected in 1976, after a ten-year-long, nationwide moratorium, and public interest in last meals was rekindled along with the debate over capital punishment. But, initially due to the rapidly merging news and entertainment industries, and eventually to the Internet, the debate was amplified and widened. In 1992, presidential candidate and Arkansas governor Bill Clinton was excoriated over his refusal to stop the execution in his state of Rickey Ray Rector, a man so mentally impaired that he asked to have the slice of pecan pie he had requested as part of his last meal saved so that he could eat it later—and that morbid fact became the story’s enduring detail. Before long, state corrections departments began posting last-meal requests on their websites. Texas, which was the first to do so, shut down its last-meals page in 2003, after it received complaints about the unseemly nature of the content.

The last meal as a cultural phenomenon grew even as capital punishment faded from public view, and in less than two centuries the country has gone from grisly public hangings, in which the prisoner was sometimes unintentionally decapitated or left to suffocate, to lethal injection, the most common form of execution in America today, in which death is “administered.” The condemned are often sedated before execution. They are generally not allowed to listen to music, lest it induce an emotional reaction. Last words are sometimes delivered in writing, rather than spoken; if they are spoken, it might be to prison personnel rather than the witnesses. The detachment is so complete that when scholar Robert Johnson, for his 1998 book Death Work, asked an execution-team officer what his job was, the officer replied: “the right leg.”

I do not amuse myself by thinking of dead people.

—Napoleon Bonaparte, 1807The public disappearance of state-sanctioned killing mirrors the broader segregation of death in an increasingly death-shy society. Dying, which had traditionally happened at home, surrounded by family and friends, began migrating into hospitals in the late nineteenth century, which is where most people die today.

Rituals like the Hangman’s Meal and the Aztec sacrificial feasts were anything but detached. They were concerned with the spirituality of death—forgiveness, salvation, appeasing the gods, marking the transition from living to dead. Although prisoners may still pray with clergy, the execution process has been drained of its spiritual and emotional content. The last meal is an oddly symbolic and life-affirming ritual in the vigorously dehumanized environment of death row. In that sense, it’s hard to see the modern last meal in America as actually being about anything.

The last meal, though, is in some ways just an extreme example of the intimate relationship between food and death that is a part of end-of-life customs in nearly all societies. Christianity, after all, tethers the very idea of death to a culinary transgression: Eve and that damned apple. The ancient Egyptians painted images of food on the walls of tombs, so that if the deceased’s ancestors ever failed in their duty to make offerings, his soul would still be nourished and comforted. Native Americans observed a variety of ceremonies involving food when a member of a tribe died. The northeastern Hurons, for example, held a farewell feast to help them die bravely: the dying man was dressed in a burial robe, shared special foods with his family and friends, gave a speech, and led everyone in song. Buddhists make food offerings to appease what the Japanese call gaki, or “hungry ghosts,” lest they return to haunt the living. Food is integral to Mexico’s Day of the Dead—which descended from Aztec festivals—when it is believed that departed souls return to earth. Graves are cleaned and repainted, and offerings of special foods—tamales and moles, sweet pan de muerto, skulls concocted of sugar (historically made of amaranth seeds), and liquor—are left for the dead to entice them to visit. And in America, food is brought to the family of the deceased after a funeral for comfort and convenience.

The Isle of the Dead V, by Arnold Böcklin, 1886. Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig, Germany.

The Chinese, especially, use food to nourish and protect the dead—ancient Chinese even buried their dead with miniature models of stoves so they could prepare meals eternally—but they also, in return, hope to secure the dead’s blessings of prosperity, good health, and fertility upon the surviving family members.

When someone dies, one of the first tasks for the family is to help the deceased break from the community—to physically leave it—and begin the transformation from corpse to ancestor. Food is central to this process, sometimes as enticement and at other times as prod. In her book The Cult of the Dead in a Chinese Village, Emily Ahern describes how in one funerary ritual, a small bowl of cooked rice and a cooked chicken head are dumped on the ground. A dog is shown the food, and once the dog gets the chicken head in its mouth, it is “beaten with a long, whiplike plant until he dashes away in a frenzy…The dog represents the dead man, the chicken head the property” that belongs to his family. The idea is to chase away the dead man and make clear that “he has enjoyed his share of the property, so he should not come back and bother the living.”

What unites these customs is an emphasis on the needs of the living, not just the dead; so too with last meals before an execution. When Susanna Margarethe Brandt sat down to the Hangman’s Meal, she signaled that she was cooperating in her own death—that she forgave those who judged her and was reconciled to her fate. Whether she actually made those concessions or not is beside the point; the officials who rendered and carried out her sentence could fall asleep that night with a clear conscience.

With the American public now excluded from the execution process, much of the larger societal meaning of capital punishment, and last meals, has been lost. The community is no longer involved. In colonial America, executions were opportunities to reinforce publicly the Calvinist belief in the innate depravity of man, and also provided a little entertainment. People thronged to see how someone facing the final mystery of life behaved. On October 20, 1790, a crowd of thousands watched thirty-two-year-old Joseph Mountain, convicted of rape, be hanged on the green in New Haven, Connecticut. Would he confess and repent, as authorities hoped, or would he die “game,” denouncing the sentence?

Over the latter half of the twentieth century, with the notion of deterrence unproven and the promise of rehabilitation mostly forgotten, retribution and general incapacitation became the primary goals of the American criminal-justice system. This was in part due to the changing political climate. The neoconservative movement rose from the ashes of Barry Goldwater’s defeat in the presidential election of 1964, tapping into public concerns about the rising crime rate, a growing disaffection for social-welfare programs, and the unrest evident in the opposition to the Vietnam War as well as urban race riots. In response came the Rockefeller drug laws in New York, which launched over thirty years of tough-on-crime policies, and Ronald Reagan’s warning of the corrosive effects of the “welfare queen” who cheats the system. “Individual responsibility” became the defining doctrine for everything from America’s economic life to its crime-fighting strategies.

The dead are often just as living to us as the living are, only we cannot get them to believe it. They can come to us, but till we die we cannot go to them. To be dead is to be unable to understand that one is alive.

—Samuel Butler, 1888In 2007 the U.S. Supreme Court effectively upheld the retributive theory of capital punishment, and the idea of individual responsibility, when it ruled that a mentally ill prisoner could not be executed if he lacked a rational understanding of why the state was killing him, even if he was aware of the facts of the state’s case. As Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the court, “It might be said that capital punishment is imposed because it has the potential to make the offender recognize at last the gravity of his crime and to allow the community as a whole…to affirm its own judgment that the culpability of the prisoner is so serious that the ultimate penalty must be sought and imposed.”

In other words, the public’s need for retribution requires criminals that are somehow irredeemable monsters who still know right from wrong and freely chose to do horrible things; they are certainly not the profoundly disabled or the unfortunate byproducts of societal or familial breakdowns. But the image of the morally culpable public enemy is difficult to sustain in a criminal-justice system that strips away the prisoner’s individuality and free will, reducing him to something seemingly less than human. It’s hard for people to experience a satisfying sense of retribution when the state is, in effect, exterminating something aberrant and abstract, much as a surgeon removes a malignant tumor.

In the nineteenth century, when the American government was ending public executions, officials struggled with a similar dilemma. Historian Louis P. Masur explains how, without the official moralizing sermons that had accompanied public hangings, people “were free to construct their own interpretations rather than receive only an official one.” There was concern that executions carried out in private could foster doubts that justice was being done—that the prisoner was in fact guilty and that the proceedings had been fair. In short, whether the convict was indeed an irredeemable monster. In an effort to reclaim control of the narrative of capital punishment, the authorities saw the benefit of the new mass-circulation newspapers to feed the public information about executions. The press accounts made it seem that the public still had some sort of informal oversight of the killing done in its name.

Daniel LaChance, an assistant professor of history at Emory University, has argued that the rituals of a last meal—and of allowing last words—have persisted in this otherwise emotionally denuded process precisely because they restore enough of the condemned’s humanity to satisfy the public’s desire for the punishment to fit the crime, thereby helping to ensure continued support for the death penalty. As LaChance puts it, “The state, through the media, reinforces a retributive understanding of the individual as an agent who has acted freely in the world, unfettered by circumstance or social condition. And yet, through myriad other procedures designed to objectify, pacify, and manipulate the offender, the state signals its ability to maintain order and satisfy our retributive urges safely and humanely.” A win-win. The state, after all, has to distinguish the violence of its punishment from the violence it is punishing, and by allowing a last meal and a final statement, a level of dignity and compassion are extended to the condemned that he didn’t show his victims. The fact that the taxpayers are picking up the tab for these sometimes gluttonous requests only bolsters the public’s righteous indignation.

The final turn of the screw is that prisoners often don’t get what they ask for. It is the request, and not what is ultimately served—let alone what’s actually consumed, which is often little or nothing—that is released to the press and broadcast to the public. Most states have restrictions on what can be served and how much of it, a monetary limit, for instance, or based on what’s in the prison pantry on a given day.

So that filet mignon and lobster tail? It’s likely to end up being chopped meat and fish sticks, according to Brian Price, an inmate who cooked final meals for other prisoners in Texas for over a decade before he was paroled in 2003 (and subsequently wrote a book about the experience called Meals to Die For). The 2001 book Last Suppers: Famous Final Meals from Death Row, includes this teaser: “How’s this for a last meal: twenty-four tacos, two cheeseburgers, two whole onions, five jalapeño peppers, six enchiladas, six tostadas, one quart of milk, and one chocolate milkshake? That’s what David Castillo, convicted murderer, packed in the night before Texas shot him up with a lethal injection.”

Film still from Looking for Alfred, directed by Johan Grimonprez, 2005. © Courtesy of zap-o-matik/Film & Video Umbrella/Sean Kelly Gallery.

What Castillo, who was executed in 1998 for stabbing a liquor-store clerk to death, actually got for his last meal was four hard-shell tacos, six enchiladas, two tostadas, two onions, five jalapeños, one quart of milk, and a chocolate milkshake. A hefty spread, but not quite the jaw-dropper he ordered.

And so it came to pass in Texas in 2011 that the state stopped offering special last meals, after Lawrence Russell Brewer ordered two chicken-fried steaks, one pound of barbecued meat, a triple-patty bacon cheeseburger, a meat-lover’s pizza, three fajitas, an omelet, a bowl of okra, one pint of Blue Bell Ice Cream, some peanut-butter fudge with crushed peanuts, and three root beers—and ended up not eating anything. This prompted an outraged state senator to threaten to outlaw the last meal if the department of corrections didn’t end the practice.

For his crackdown on taxpayer-funded excess, the senator surely earned hearty handshakes from his tough-on-crime constituents. But it is somehow fitting that the sham of the last meal, in Texas at least, which has executed hundreds more people over the last thirty years than any other state, was allowed to fade into history with its bundle of contradictions intact, buried by the calculated denunciation of a politician seizing on a way to stroke his base. Now in the Lone Star State, the men and women killed by the government get whatever is on the prison menu that day. Justice will be served.