Ours is an age which consciously pursues health, and yet only believes in the reality of sickness.

—Susan Sontag, 1963Safety First

Thomas Mann uncovers a hidden cholera epidemic.

During his fourth week at the Lido, Gustav von Aschenbach made several sinister observations touching on the world about him.

First, it seemed to him that as the season progressed, the number of guests at the hotel was diminishing rather than increasing; and German especially seemed to be dropping away, so that finally he heard nothing but foreign sounds at table and on the beach. Then one day in conversation with the barber, whom he visited often, he caught a word that startled him. The man had mentioned a German family that left soon after their arrival; he added glibly and flatteringly, “But you are staying, sir. You have no fear of the plague.” Aschenbach looked at him. “The plague?” he repeated. The gossiper was silent, made out as though busy with other things, ignored the question. When it was put more insistently, he declared that he knew nothing, and with embarrassing volubility, he tried to change the subject.

That was about noon. In the afternoon there was a calm, and Aschenbach rode to Venice under an intense sun. While sitting over his tea at his little round iron table on the shady side of the Piazza San Marco, he suddenly detected a peculiar odor in the air that, it seemed to him now, he had noticed for days without being consciously aware of it. The smell was sweetish and drug-like, suggesting sickness and wounds and a suspicious cleanliness. He tested and examined it thoughtfully, finished his luncheon, and left the square on the side opposite the church. The smell was stronger where the street narrowed. On the corners printed posters were hung, giving municipal warnings against certain diseases of the gastric system liable to occur at this season, against the eating of oysters and clams, and also against the water of the canals. The euphemistic nature of the announcement was palpable. Groups of people had collected in silence on the bridges and squares; and the foreigner stood among them, scenting and investigating.

At a little shop he inquired about the fatal smell, asking the proprietor, who was leaning against his door surrounded by coral chains and imitation amethyst jewelry. The man measured him with heavy eyes and brightened up hastily. “A matter of precaution, sir!” he answered with a gesture. “A regulation of the policy that must be taken for what it is worth. This weather is oppressive, the sirocco is not good for the health. In short, you understand—an exaggerated prudence perhaps.” Aschenbach thanked him and went on. Also on the steamer back to the Lido, he caught the smell of disinfectant.

Returning to the hotel, he went immediately to the periodical stand in the lobby and ran through the papers. He found nothing in the foreign-language press. The domestic press spoke of rumors, produced hazy statistics, repeated official denials, and questioned their truthfulness. This explained the departure of the German and Austrian guests. Obviously, the subjects of other nations knew nothing, suspected nothing, were not yet uneasy. “To keep it quiet!” Aschenbach thought angrily as he threw the papers back on the table. “To keep that quiet!”

Bent on getting reliable news of the condition and progress of the pestilence, he ransacked the local papers in the city cafés, as they had been missing from the reading table of the hotel lobby for several days now. Statements alternated with disavowals. The number of the sick and dead was supposed to reach twenty, forty, or even a hundred and more—and immediately afterward every instance of the plague would be either flatly denied or attributed to completely isolated cases that had crept in from the outside. There were scattered admonitions, protests against the dangerous conduct of foreign authorities. Certainty was impossible. One day at breakfast in the large dining hall, he entered into a conversation with the manager, that softly treading little man in the French frock coat who was moving amiably and solicitously among the diners and had just stopped at Aschenbach’s table for a few passing words. Just why, the guest asked negligently and casually, had disinfectants become so prevalent in Venice recently? “It has to do,” was the evasive answer, “with a police regulation, and is intended to prevent any inconveniences or disturbances to the public health that might result from the exceptionally warm and threatening weather.”

“The police are to be congratulated,” answered Aschenbach; and after the exchange of a few remarks on the weather, the manager left.

Yet that same day, in the evening, after dinner, it happened that a little band of strolling singers from the city gave a performance in the front garden of the hotel. Two men and two women, they stood by the iron post of an arc lamp and turned their whitened faces up toward the large terrace where the guests were enjoying this folk recital over their coffee and cooling drinks. The hotel personnel, bellboys, waiters, and clerks from the office could be seen listening by the doors of the vestibule. Mandolin, guitar, harmonica, and a squeaky violin were responding to the touch of the virtuoso beggars. Instrumental numbers alternated with songs, as when the younger of the women, with a sharp trembling voice, joined with the sweetly falsetto tenor in a languishing love duet. But the real talent and leader of the group was undoubtedly the other of the two men, the one with the guitar. He was a kind of buffo baritone, with not much of a voice, although he did have a gift for pantomime and a remarkable comic energy. Often, with his large instrument under his arm, he would leave the rest of the group and, still acting, would intrude on the platform, where his antics were rewarded with encouraging laughter.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, by Albrecht Dürer, c. 1497. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Felix M. Warburg, 1940.

Aschenbach sat on the balustrade, cooling his lips now and then with a mixture of pomegranate juice and soda that glowed ruby red in his glass in front of him. His nerves took in the miserable notes, the vulgar crooning melodies; for passion lames the sense of discrimination and surrenders in all seriousness to appeals that, in sober moments, are either humorously allowed for or rejected with annoyance. At the clown’s antics, his features had twisted into a set painful smile. He sat there relaxed, although inwardly he was intensely awake.

The guitar player began a solo to his own accompaniment, a street ballad popular throughout Italy. It had several strophes, and the entire company joined each time in the refrain, all singing and playing, while he managed to give a plastic and dramatic twist to the performance. Yet what really prompted Aschenbach to pay him keen attention was the observation that the questionable figure seemed also to provide its own questionable atmosphere. For each time they came to the refrain, the singer, amid buffoonery and familiar handshakes, began a grotesque circular march that brought him immediately beneath Aschenbach’s place; and each time this happened, there blew up to the terrace from his clothes and body a strong carbolic smell. After the song was ended, he came up to Aschenbach, and along with him the smell, which no one else seemed concerned about.

“Listen!” Aschenbach said in an undertone, almost mechanically. “They are disinfecting Venice. Why?”

The jester answered hoarsely, “On account of the police. That is a precaution, sir, with such heat, and the sirocco. The sirocco is oppressive. It is not good for the health.”

He spoke as though astonished that anyone could ask such things, and demonstrated with his open hand how oppressive the sirocco was.

“Then there is no plague in Venice?” Aschenbach asked quietly, between his teeth.

The clown’s muscular features fell into a grimace of comical embarrassment. “A plague? What kind of plague? Perhaps our police are a plague? You like to joke! A plague! Of all things! A precautionary measure, you understand! A police regulation against the effects of the oppressive weather.” He gesticulated.

“Very well,” Aschenbach said several times curtly and quietly; and he quickly dropped an unduly large coin into the hat. Then with his eyes he signaled the man to leave. He obeyed, smirking and bowing. But he had not reached the stairs before two hotel employees threw themselves upon him, and with their faces close to his began a whispered cross-examination. He shrugged his shoulders; he gave assurances, he swore that he had kept quiet—that was evident. He was released, and he returned to the garden; then after a short conference with his companions, he stepped out once more for a final song of thanks and leave-taking.

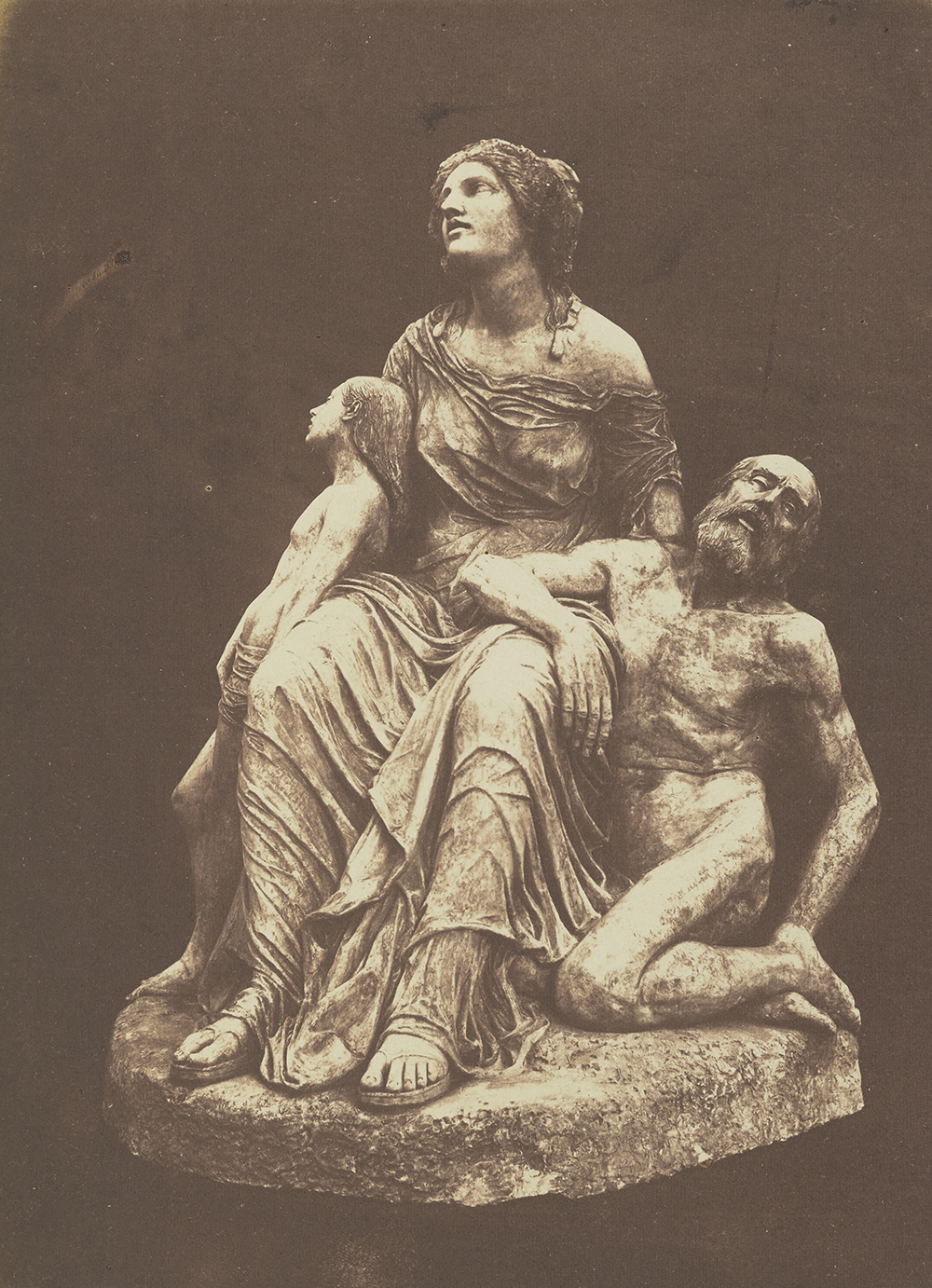

Cholera, by Antoine Étex, 1851. Photograph by Claude-Marie Ferrier. © The J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

The following day, in the afternoon, Aschenbach walked from the Piazza San Marco into the English travel bureau located there; and after changing some money at the cash desk, he put on the expression of a distrustful foreigner and launched his fatal question at the attendant clerk. He began, “No reason for alarm, sir. A regulation without any serious significance…” But as he raised his blue eyes, he met the stare of the foreigner, a tired and somewhat unhappy stare focused on his lips with a touch of scorn. Then the Englishman blushed. “At least,” he continued in an emotional undertone, “that is the official explanation, which people here are content to accept. I will admit that there is something more behind it.” And then in his frank and leisurely manner he told the truth.

For several years now Indian cholera had shown a heightened tendency to spread and migrate. Hatched in the warm swamps of the Ganges delta, rising with the noxious breath of that luxuriant, unfit, primitive world and island wilderness shunned by humans and where the tiger crouches in the bamboo thickets, the plague had raged continuously and with unusual strength in Hindustan, had reached eastward to China, westward to Afghanistan and Persia, and, following the chief caravan routes, had carried its terrors to Astrakhan and even Moscow. But while Europe was trembling lest the specter continue its advance from there across the country, it had been transported over the sea by Syrian merchantmen, and had turned up almost simultaneously in several Mediterranean ports, had raised its head in Toulon and Málaga, had showed its mask several times in Palermo and Naples, and seemed permanently entrenched through Calabria and Apulia. The north of the peninsula had been spared. Yet in the middle of this May in Venice, the frightful vibrios were found on one and the same day in the blackish wasted bodies of a cabin boy and a woman who sold groceries. The cases were kept secret.

But within a week there were ten, twenty, thirty more, and in various sections. A man from the Austrian provinces who had made a pleasure trip to Venice for a few days returned to his hometown and died with unmistakable symptoms—and that is how the first reports of the pestilence in the lagoon city got into the German newspapers. The Venetian authorities answered that the city’s health conditions had never been better, and took the most necessary preventive measures. But probably the food supply had been infected. Denied and glossed over, death was eating its way along the narrow streets, and its dissemination was especially favored by the premature summer heat, which made the water of the canals lukewarm. Yes, it seemed as though the plague had got renewed strength, as though the tenacity and fruitfulness of its stimuli had doubled. Cases of recovery were rare. Out of a hundred attacks, eighty were fatal, and in the most horrible manner. For the plague moved with utter savagery, and often showed that most dangerous form, which is called “the drying.” Water from the blood vessels collected in pockets, and the blood was unable to carry this off. Within a few hours the victim was parched, his blood became as thick as glue, and he stifled amid cramps and hoarse groans. Lucky for him if, as sometimes happened, the attack took the form of a light discomfiture followed by a profound coma from which he seldom or never awakened.

I have learned much from disease which life could never have taught me anywhere else.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1830At the beginning of June, the pesthouse of the Ospedale Civico had quietly filled; there was not much room left in the two orphan asylums, and a frightfully active commerce was kept up between the wharf of the Fondamenta Nuove and San Michele, the burial island. But there was the fear of a general drop in prosperity. The recently opened art exhibit in the public gardens was to be considered, along with the heavy losses that in case of panic or unfavorable rumors would threaten business, the hotels, the entire elaborate system for exploiting foreigners—and as these considerations evidently carried more weight than love of truth or respect for international agreements, the city authorities upheld obstinately their policy of silence and denial. The chief health officer had resigned from his post in indignation and been promptly replaced by a more tractable personality. The people knew this; and the corruption of their superiors, together with the predominating insecurity, the exceptional condition into which the prevalence of death had plunged the city, induced a certain demoralization of the lower classes, encouraging shady and antisocial impulses that manifested themselves in license, profligacy, and a rising crime wave. Contrary to custom, many drunkards were seen in the evenings; it was said that at night nasty mobs made the streets unsafe. Burglaries and even murders became frequent, for it had already been proved on two occasions that persons who had presumably fallen victim to the plague had in reality been dispatched with poison by their own relatives. And professional debauchery assumed abnormal and obtrusive proportions such as had never been known here before, and to an extent that is usually found only in the southern parts of the country and in the Orient.

The Englishman pronounced the final verdict on these facts. “You would do well,” he concluded, “to leave today rather than tomorrow. It cannot be much more than a couple of days before a quarantine zone is declared.”

“Thank you,” Gustav Aschenbach said, and left the office.

Thomas Mann

From Death in Venice. About a week after Mann and his wife arrived in Venice for a seaside vacation, Venetian police confiscated and destroyed two thousand pamphlets distributed by local medical professionals warning residents and tourists of an emerging cholera outbreak. According to notes Mann kept while writing this novella, which he described to a friend as “a really strange thing that I brought with me from Venice,” the protagonist, Gustav Aschenbach, arrives in Venice on June 2, 1911, the same day that the Manns, having learned of the epidemic, cut their vacation short and returned home to Munich.