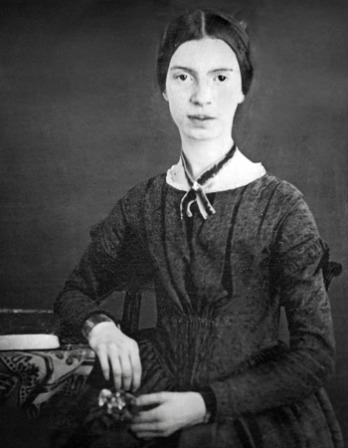

Marguerite Gardiner

Conversations of Lord Byron,

1834

Conversations of Lord Byron,

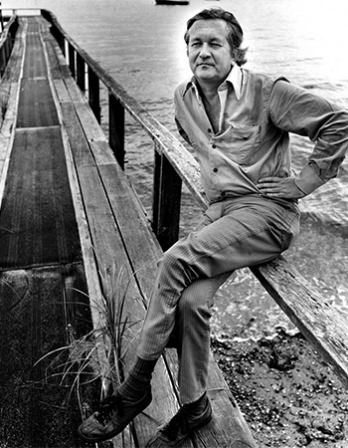

Lord Byron is evidently in delicate health, brought on by starvation and a mind too powerful for the frame in which it is lodged. He is obstinate in resisting the advice of medical men and his friends, who all have represented to him the dangerous effects likely to ensue from his present system. He declares that he has no choice but that of sacrificing the body to the mind, as that when he eats as others do he gets ill and loses all power over his intellectual faculties; that animal food engenders the appetite of the animal fed upon; and he instances the manner in which boxers are fed as a proof, while, on the contrary, a regimen of fish and vegetables served to support existence without pampering it. I affected to think that his excellency in and fondness of swimming arose from his continually living on fish, and he appeared disposed to admit the possibility, until, being no longer able to support my gravity, I laughed aloud, which for the first minute discomposed him, though he ended by joining heartily in the laugh, and said, “Well, Miladi, after this hoax never accuse me any more of mystifying; you did take me in until you laughed.”

Nothing gratifies him so much as being told that he grows thin. This fancy of his is pushed to an almost childish extent, and he frequently asks, “Don’t you think I get thinner?” or, “Did you ever see any person so thin as I am who was not ill?” He says he is sure no one could recognize him were he to go to England at present, and seems to enjoy this thought very much.