Trench watch, c. 1916.

In The Burning of the World, his recently discovered memoir of the first few weeks of World War I, the Hungarian artist, officer, and man about town Béla Zombory-Moldován writes frequently about his attachment to his watch. When he’s wounded in the confusion of battle in the forests of Galicia, he finds the watch unscathed during an agonizing evacuation of the area, and exalts the survival of “my trusty companion, sharer of my fate, the comrade that connected me to my former life.” Much more than a watch, it’s almost a miracle: “Not just an object, but a true and staunch friend. I held it in my left hand and marveled at it as it measured off the seconds.”

How to tell time was a matter of survival and strategy during the Great War, a war in which communication technologies had to advance rapidly to keep pace with the new instruments of battle. The war was a crucible of innovation in destruction, in which chlorine gas, tanks, and heavy artillery choked, crushed, and obliterated human bodies in new ways. Vast armies dug in opposite each other across unprecedented distances—the Western Front alone stretched well over four hundred miles, from the Swiss border to the North Sea. Because much of the infantry went underground, it was no longer possible simply to holler or sound a hunting horn as a signal to attack, nor for regiments to advance proudly, and visibly, together on horseback. Instead, it became necessary to coordinate time and to tell it accurately; the practice and the phrase synchronize watches was born from this need during the war. Officers in crowded trenches watched for second hands to tick down before blowing the whistle and rallying their men, who scrambled up ladders into the awaiting gunfire. The term zero hour, the moment of no return, was first recorded in the New York Times in November 1915: “At 5:05 a.m. September 25 a message came to the dugout that the ‘zero’ hour, that is, the time the gas was to be started, would be at 5:50 a.m.” The irony of ascribing a precise time for an attack as uncontrollable and weather-dependent as gas goes unmentioned.

Paul Fussell, in his influential 1975 study The Great War and Modern Memory, notes that sunrise and sunset dominated soldiers’ trench lives and their understanding of the passage of time. These periods of “stand-to” were times of heightened tension and observation, when men would keep watch on the raised fire step and strain their eyes through field glasses for movement. When it wasn’t raining, the skies above the flat, endless fields would burst into color as they waited—an unforgettable combination of beauty and terror. (Fussell writes that “dawn has never recovered from what the Great War did to it.” Dawn and dusk were unavoidable natural markers of time, both ordinary and mystical. “The darkness crumbles away./It is the same old druid Time as ever,” as Isaac Rosenberg puts it in his 1916 poem “Break of Day in the Trenches.” Dawn is relentless, and soldiers are powerless to hide from it, speed it up or slow it down. A watch then gives the illusion of controlling time, a sustaining fantasy of life at the front. As Zombory-Moldován suggests, the watch is something more than practical; it’s a link back to a world where a man was free to make his own appointments, to run his own life.

Since the eighteenth century, gentlemen who needed to tell time—and wanted to display their wealth—carried pocket watches, either an open-faced design or a model with a spring-loaded cover to protect its delicate hands and face from damage. Most ordinary people didn’t need to know that it was seven thirty in the evening rather than dusk; they told time by church bells, sunrises, and habit. It wasn’t until the expansion of railroads in the middle of the nineteenth century that minutes truly became measured, timetabled, and synchronized. But for a solider going to war, a pocket watch was cumbersome and fragile; it took time to remove it from a pocket, open the case, and put it away safely. The alternative, strapping a watch to one’s wrist, seemed obvious but presented a quite different, and stickier, problem. “Wristlets,” as they were known until the 1920s, were designed for women. As the name implies, they were essentially bracelets designed for showing off jewels (and shapely wrists), and were equipped with a tiny watch face for decoration rather than practicality. It would take one of the twentieth century’s greatest rebranding campaigns to persuade military men to strap time to their wrists.

The company that would become Rolex already understood the importance of branding. Hans Wilsdorf, a twenty-four-year-old German orphan who had apprenticed with a Swiss watchmaker, founded a company in London in 1905 to import small, precise watch movements from Switzerland. The business was initially called Wilsdorf & Davis, after the founder and his brother-in-law and partner, Alfred Davis. Wilsdorf invented the name “Rolex” a few years later and incorporated the company under that name in 1915, by which point it was simple common sense for a British business to shed any German associations. Wilsdorf claimed that he simply combined letters of the alphabet until he found a combination that was easy to pronounce in any language and short enough to fit on a small watch face. He later mythologized the moment of creation—“One morning, while riding on the upper deck of a horse-drawn omnibus along Cheapside in the City of London, a genie whispered ‘Rolex’ in my ear”—and suggested that the name mimicked the sound a watch made when it was being wound. The quest for the perfect name was reflected in Wilsdorf’s pursuit of accuracy, and his determination to transform the image of the wristwatch. By the outbreak of the war, Rolex had been awarded certificates of “chronometric precision” from Bienne, Switzerland, and Kew Observatory in London, distinctions that had never before been awarded to a “bracelet watch.” Watchmakers had triumphed over the technical challenges; now the problem was sex.

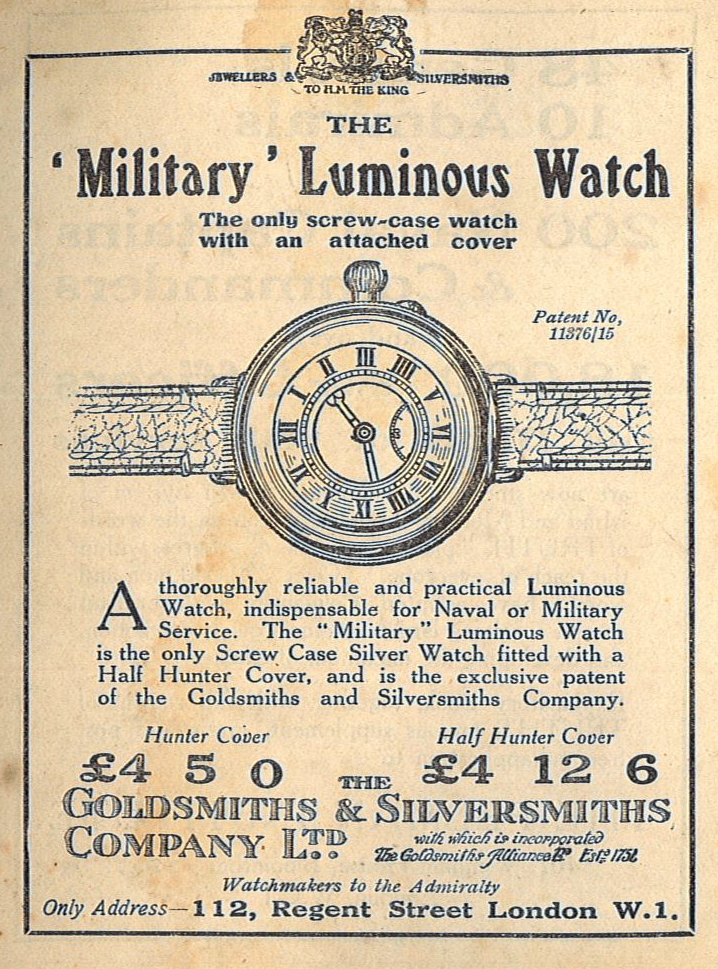

The testimony of military officers had already started to shift the gender of the wristlet. A British officer who relied on his watch during the Boer War of 1899–1902 was quoted prominently in the 1901 edition of the Goldsmiths Company Watch & Clock Catalog: “I wore it continually on my wrist in Africa for three and a half months. It kept most excellent time, and never failed me.” When World War I began, the importance of timekeeping for officers, and the wet, muddy trench conditions led to a race among watchmakers to develop the hardiest and most reliable wristwatch—not just a pocket watch on a leather strap, but an integrated design with illuminated dials that could be read easily at a glance. The British military brass remained unconvinced, however, and the “trench watch,” a pocket watch in a double-sided metal case, remained official issue. The United States government had more faith; when the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Signal Corps officers were issued wristwatches specially manufactured by Zenith.

The luxury watch companies Omega, Longines, Cartier, and Rolex, all worked on developing battle-ready wristwatches, and their advertising campaigns strenuously asserted the masculinity of the accessory. A wartime advertisement for Waltham equates the wristwatch with a soldier’s deadlier accoutrements. Under the headline, “Marking His Man,” the copy makes the link explicit: “Tommy’s coolness and a perfect rifle enable him to do it. If the rifle jammed at critical moments where would Tommy be? It’s the same with his wristlet watch. When it’s a Waltham, he has a mechanically perfect watch which does not go wrong, which can be relied upon to keep good time in camp or trenches.” Other advertisements, such as those by the English gentlemen’s outfitters Thresher & Glenny and the Swiss manufacturer Electa, relied on a simpler motif of a strapping officer staring manfully at his wrist. In 1916, the field manual Knowledge for War: Every Officer’s Handbook for the Front contained a list of essential items for an officer’s kit; at the very top, ahead of a gun and a water bottle, is a “luminous wristwatch with unbreakable glass.”

A 1919 Bulova advertisement makes clear how far the wristwatch had to go to become accepted in America. “No more is it considered dandyfied for men to wear a strap watch on the wrist.” On February 15, 1918, the Stars and Stripes military newspaper (edited during the war by Harold Ross, the postwar founder of the New Yorker) ran an extraordinary piece titled “The Wrist Watch Speaks,” which vividly underscores the sexualized panic that had surrounded these “bejeweled and fragile” timepieces.

I was also worn by lounge lizards, the boys who had their handkerchiefs tucked up their sleeves, who would as soon be seen without their highly polished canes as without their trousers, the little lads who tried to sport monocles and endeavored in vain to grow mustaches and to cultivate un-American accents. I was the mark of the woman and the she-man.

The war had turned this symbol of unmanliness into a military tyrant. “Everything that is done in the army itself, that is done for the army behind the lines, must be done according to my dictates.” But its proclivities still seem to be in question. “On the hairy forearms of the husky artillerymen, I am there with every tug of the lanyard, and can feel the firm biceps tighten from below.”

The ultimate expression of control over time in World War I was the declaration of the armistice at Compiègne, France, at 11 a.m. on 11/11/1918. The agreement was made and signed between the German and Allied delegations a little after five o’clock in the morning, but the symmetry of the elevens, and perhaps the biblical symbolism of the “eleventh hour,” the last possible minute, proved irresistible. The news traveled faster to the major European capitals than it did to men at the front, who continued fighting, and it is estimated that some ten thousand men were killed or wounded on November 11, including over three thousand American casualties. For years afterward, clocks and watches throughout the British Commonwealth would be synchronized to eleven a.m. for the observation of a precise two minutes’ silence, the centerpiece of memorial rituals. This chronometric ritual was accompanied by the recitation of a verse from Laurence Binyon’s 1914 poem “For the Fallen,” which acknowledged the continuing power of older, natural ways of marking time and loss, demonstrating the importance of these two very different but inextricable systems, ancient and modern, of keeping time in war: “At the going down of the sun, and in the morning/We will remember them.”