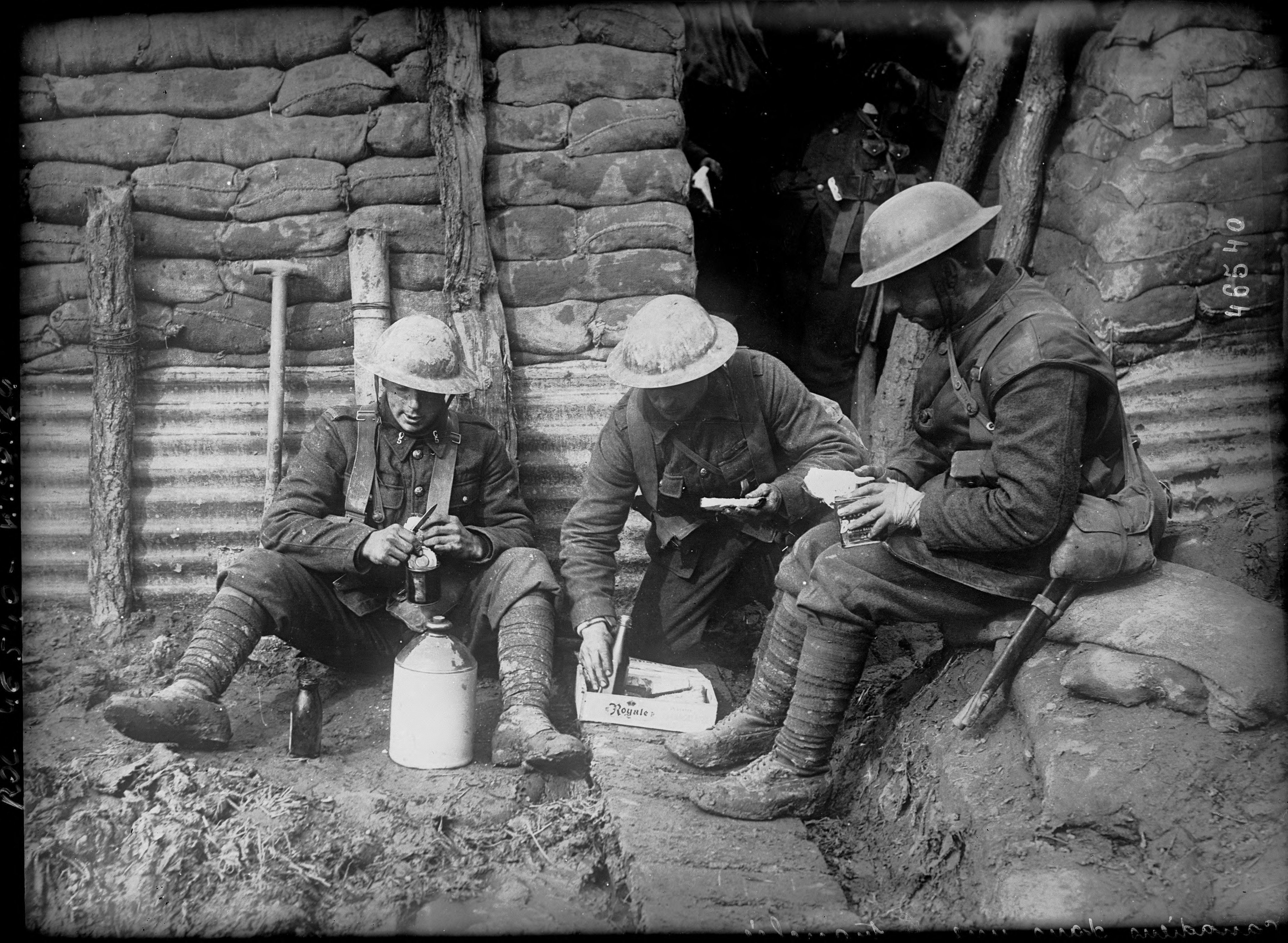

Canadian soldiers resting in a trench, c. 1917.

Socialites, rich Americans returning from European tours, British aristocracy, and diplomats vied for tickets on the maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic. These were some of the most cosmopolitan people on the globe, endowed with money to travel widely and sojourn in exotic places and graced with access to their peers at every destination. Savvy, experienced, knowing foreign cities and ways, typically comfortable in French—the lingua franca of the belle époque—such passengers could easily consider themselves citizens of the world. Yet on board, the cosmopolitanism of the rich and powerful met its limits in the sequestered third-class passengers. To the men and women who commanded the upper decks, such people were doubly foreigners—separated by class and nationality. Conditions for poorer passengers on the Titanic were, in fact, considerably better than on many liners of the period, but the White Star Line’s efforts to attract such customers did not extend to any provision for the mixing of classes. Below deck, a less spectacular form of cosmopolitanism played out, mixing people from Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle and Far East—a polyglot community bringing people into innumerable small encounters with foreign others, undoubtedly provoking tensions, but also opening, tentatively, toward understanding, interactions, and transactions.

When we consider cosmopolitanism, we may think of first-class passengers whose openness to other people, foreign places, and unfamiliar cultural experiences derives from education, outlook, aesthetic appreciation, and perhaps even an ethical commitment to universalism. Still, it is important to remember the cosmopolitanism of steerage, an opening to the foreign that emerges from necessity and fate, and grows through encounter, mixing, and negotiation within culturally complex social settings. Starting as a form of getting along, a modus vivendi among people brought together by circumstance, it may grow into an appreciation of the other’s difference. Fittingly, scholars have of late begun to distinguish between ethical, aesthetic, and philosophical forms of cosmopolitanism and what they call banal or everyday cosmopolitanism, between elite cosmopolitanism and cosmopolitanism from below—quite literally, in the case of the Titanic.

News of the great ship’s sinking took days to reach the village of Swan Lake, a speck in the vast Canadian prairie and—despite its unintended association with the glamour of Russian ballet—a world away from the glittering lights of first class and the dimmer glow of steerage. My grandfather George Hambley was sixteen in that April of 1912, the second youngest of ten children born to a couple who had broken ground on a small land-grant farm near the town. Overwhelmed by the ship’s immensity, George spent the day behind an ox-drawn plow, methodically counting out the length of the Titanic again and again. Three years later, the RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship, carried him from Halifax to Liverpool, along with thousands of other Canadian soldiers. Another four years, and George was a seasoned veteran of the Great War, waiting impatiently in England, hoping it would again be the Olympic, that would bear him back home. He journeyed to Europe the son of pioneers and returned a cosmopolitan. Like Titanic’s unlucky third-class passengers, he became a cosmopolitan by circumstance—although it was neither transit in steerage nor combat, but rather encounter with the enemy in the aftermath of war, that made him so.

Enlisting in the autumn of 1915, George reached France in October 1916. He was a horse soldier, attached to the Canadian Light Horse in the British Expeditionary Force. Being a cavalryman on the Western Front meant just about everything except riding a horse into combat. He rode dispatch, mended communications lines, dug saps under the German line, manned a machine gun, and by late 1918 had been accepted into the Air Corps. Only after the failure of the great German offensive in the spring of 1918 did the Western Front become mobile, and with mobility mounted troops regained some of their utility. Admittedly, the great breakthrough that Field Marshal Douglas Haig had always hoped for never happened. So the chief rationale for maintaining a great British cavalry years after the German high command had essentially disbanded the cavalry in the West proved groundless. Still, the cavalry played its part in repulsing the Germans at Amiens and in the Hundred Days Offensive that led up to the Armistice, providing reconnaissance and engaging in skirmishes, and a few memorable if, invariably, very costly charges. One of those, on October 10, 1918, near Cambrai, perhaps the last cavalry charge on the Western Front had exacted a heavy toll on George’s squadron. George’s beloved horse, Nix, was one of the casualties, felled by a machine-gun bullet to the temple in the first 200 meters of the charge. This episode is carefully chronicled in George’s diary, as are many experiences during his years of frontline combat. By the time George returned to Canada in the late spring of 1919, he had produced twenty volumes of varied shape and size, a cache that some historians consider the most valuable diaries of a Canadian enlisted man in the First World War.

George’s account of the weeks immediately after Armistice is at least as intriguing as his chronicle of the combat years. He was among the first Allied troops to march into Germany and occupy the defeated land. Entering Germany after long years of bitter conflict and an incessant barrage of propaganda demonizing the Hun—at the end of a war that spawned the modern habit of gross dichotomizing—he recounts in his diary surprisingly intimate interactions with Germans and a humane empathy toward the vanquished enemy. Written under the most charged of circumstances, the diary affords a glimpse into the ordinary ways in which the martial spirit might be demobilized, animosities made milder, human contact re-established across enemy lines, and breaches opened in the wall of mutual misunderstanding.

George’s wartime diaries reveal an earnest young man, a devout Christian given to self-scrutiny of an intensity reminiscent of a seventeenth-century Puritan. He lived his life like he was brandishing a standard emblazoned with the slogans of the late Victorian world, all capitalized: TRUTH, HONOR, DUTY, SELF-MASTERY. Though he frequently tut-tutted his comrades for their drinking, foul language, and womanizing, he loved them and forgave them almost everything, even as he recorded his own struggles with temptations and the peaks and troughs of his own morale. Despite his capacity for priggery, his curiosity was wide-ranging and he was always bent upon self-improvement and expansion of his knowledge.

On the day the fighting ceased, George was in Mons, France, scene of the British Expeditionary Force’s first great action and subsequent retreat southward in 1914. On this day in November 1918, the tables were turned and the Germans were exiting the city even as British troops occupied its center. George’s squadron was ordered to enforce the withdrawal of German forces. It embarked by November 15 on a long march toward the Rhineland, with George mounted on a new horse, Knight. They reached the German frontier on December 4. They entered the country, notes George, as “victors,” but that did not assuage the soldiers’ anxieties. He spent his first night in Germany uncomfortably billeted with a family. Absent were the kind manners of the French and Belgians who had put him up along the route. “We are the enemies of these people,” he noted, speaking in the next breath of a Belgian officer rumored to have been knifed by a hostess and of Belgian POWs reportedly killed by a mob in Cologne. Certainly, the Allied command viewed the occupation in harsh terms. George summarized Haig’s order, disseminated in both English and German, that the “civilian population are to receive no consideration whatever at our hands. Death is to be the penalty for striking a soldier in any way.” His hosts feared him, and rightly so, he noted; but he feared his hosts. Despite the mutual anxiety of this first encounter, George surmised that these people “appear to have good hearts.” Once they decided the Canadians were not “barbarians,” the daughters of the household invited him and his companion to sit at the stove. “We cannot hate these people even though we hate the German name and are disgusted at their barbarities,” he quickly concluded. George draws a familiar division in recognizing the value of individuals while reviling the group to which they belong, but perhaps this is a particularly common stepping stone in the development of everyday cosmopolitanism. After all, positive encounters with individuals may cause—by no means inevitably—the gradual erosion of stereotypes of the alien. Growing from concrete contacts within a setting of practical interactions, a learning process of this sort would invert a more philosophically motivated cosmopolitanism that begins with abstractions such as humanity, or world, or world citizenship and then descends to encounters with individuals.

In the ensuing days, the squadron made its way toward Cologne. Despite the external circumstances—a vanquished enemy that had fought to the point of total defeat—as well as the harsh terms set by Allied command, George’s dealings with Germans thickened. Of the families obliged to billet him, he usually judged them to have “good hearts.” By the time the squadron left Brühl, southwest of Cologne, after three days there, they “had to say many goodbyes as we make friends everywhere.” Although the cavalry entered Cologne in full martial form, on horseback and with swords “at the slope,” George took every opportunity to wander the streets like a tourist. People seemed ready and even eager to talk about the war. He recorded many conversations, such as an exchange with an “intelligent young fellow who could speak English.” The boy was delighted that the war ended when it did, being just one month away from draft age, and he wished Holland would return the abdicated Kaiser to Germany for trial and execution, a theme that surfaced often. In one home, the woman brought out photos of a son killed at the front. Noting that “she is a mother,” even if she is a “German,” George tried to comfort her as she wept by recalling her luck that her other son, just returned from the front, had survived and was even then bunking in his childhood bed. He recounted a long talk with a Jesuit in Cologne who seemed disaffected with the modern world in its entirety and wished a pox upon both sides. Not all discussions were to George’s satisfaction. Showing perhaps a little too much zealous faith in the power of a righteous cause, he complained it could be hard to get the Germans to “understand the real issues of the war” and “persuade” them, though he doesn’t specify of what—presumably, of Germany’s war guilt. Nor were all encounters to his taste. Visiting Cologne one day, he ducked into an elegant café, where the men at the Stammtisch struck him as “examples of the purest Hunism on record—Deutsche beards, Herrmann mustaches, Kaiser curled mustaches—the fat portly well-fed fully satisfied German under whom I would love to place a Mills bomb.” This single moment of fantasized aggression seemed provoked as much by an encounter with the wealthy, in this case perceived as war profiteers, as with Germans per se. It is as if the alienating differences of class might in the end be stronger than those of nationality. A common soldier thrown among the ordinary people of a defeated land, George was in some sense a passenger in steerage, launched by necessity into a common situation and thereby discovering common ground with the enemy—that is, until he wandered into the equivalent of the first-class lounge. This distasteful experience notwithstanding, George mused after a couple of weeks that, “even here in Germany, we find good and bad people.” What in a different context would be the most banal of commonplaces becomes a nuanced observation after years that had depicted the enemy as an undifferentiated malicious mass.

Shortly after the New Year, the squadron moved to the small town of Bad Godesberg, just south of Bonn. On the long march from Mons in late November, George had whiled away his time reading Goethe in translation, but once in Bad Godesberg, he dallied in the world of Romantic Teutonic myth that had set the classicist Goethe’s teeth on edge but had provided material for Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle. It was a scene ready-made for reveries. Godesberg sits on the Rhine River, its view dominated by the Drachenfels, a tall hill rising abruptly from the eastern shore. Legend has it that Siegfried, hero of the Nibelungenlied, slew the dragon Fafnir on its slopes and bathed in the dragon’s blood to become invulnerable. A hike up the Drachenfels still brings one to the Nibelungenhalle, a shrine to Wagner’s operas built in 1913 and a perfect example of the way cultural obsessions were pressed into the service of nationalist myth-making on the eve of the Great War. Fittingly, a steamer named Rheingold carried George on a two-day sightseeing voyage in mid-January. As the cruise neared its end, he gave in to the lure of this myth-saturated place. He awoke in the dusk to “see a huge rock-like summit towering above us—I thought for quite a minute—then I knew it was the bulky heights of the Drachenfels looming up against the lighter color of the sky—maybe that the spirit of the Dragon was still up there searching for rest in the old Dragon’s Hole, or dreaming of his victims of the days of long past and forgotten. Perhaps upon these shores that he loved so well, the unquenchable spirit of Siegfried still wanders.”

George was billeted with the Lethgau family, and there he came down with the Spanish flu, which was beginning its rapid spread into the global pandemic that claimed more lives than the Great War. He was delirious for fourteen days, and through his sickness Gerda, the Lethgau’s nineteen-year-old daughter, nursed him. Spending long hours together, a passion blossomed between them. George viewed Gerda as something of a coquette, perhaps too ready to tell him about her “love affairs” and “affaires de coeur” and eager to test her powers on him. But he believed her when she claimed she had never kissed a man. For them, kissing was a game in which the deck held only hearts, but it was also a dangerous flirtation with ruin. Eager to play the game, he nonetheless held to the chaste limits he had never relaxed even in the squalor of the front, resolving not to jeopardize the girl’s good standing. As he had with others in the weeks since reaching Germany, he engaged her in long conversations about the war, and spoke with admiration of her knowledge of the course of events. She spent time convincing George that the Germans were not barbarians. Unlike some of his interlocutors, she did not incline to blame the Kaiser, but insisted it had been a defensive war against Russian aggression.

Describing himself as a “huge lobster of an ugly bearish sort of creature,” he thought himself an unlikely object of a woman’s interest. Still, he clearly enjoyed her attentions. He reveled in feminine company after the harsh years in France, but he obviously struggled with their position, he being an “enemy theoretically, but in practice her very warm friend.” He recognized that “if I found a girl whom I really loved and she reciprocated it I would not care what her land nor where her home because even German girls have good hearts. And I may add for my future reference that I have come as near loving this dainty little thing as I have been to loving any other girl.” He alternated between calling her his Schmetterling, his butterfly, and his Godesberg Lorelei, that siren of ancient lore whose beauty lured sailors to calamity on a rock by the Rhine.

Around two months after their arrival in Godesberg, the squadron was ordered to leave. It was a poignant parting, though George’s diary strikes a tone of bravado. Recollections years later sound a more Wagnerian note: “We recalled the day we climbed to the top of the old tower that overlooks the city, the Castle, where we did have so much fun and happy laughter. There we looked across the river, and I loved the sound of her voice as Gerda said, ‘They are Das Siebengeberge [the Seven Hills], and there you can see the Drachenfels where Siegfried killed the bad old dragon. Yes,’ she said, ‘As you go over the water of the river you can still see his bones down in the water.’ She showed me the picture of the death of Siegfried, Siegfriedstod and the strange haunting darkness of the picture showing the death of the Gods, Götterdämmerung. As she spoke of them her voice had a quiet sweet earnestness, for she seemed to live again the spirit of the great pictures, and she loved the romantic connotation behind such loveliness.” Marching out the next morning, the soldiers paraded in the town square before a gathering of women, children, and old men. “We could hardly believe that we had only been there about two months, but somehow the town seemed to have taken us to their hearts. The streets on all sides were crowded with women and girls to say goodbye. Many girls were crying and I suppose our squadron had never had a more pathetic send-off. Every man had friends, and had found a home, officers and all. Some of the men said that there would be many children there who would be good Canadians, but I didn’t think of lovely Gerda in that light.”

Shortly after, George received his demobilization order and made his way back toward England, spending time in Paris and revisiting sites on the Western Front where he had seen action.

George was not blind to the limits of those encounters that form the theme of his German chronicle. Years later, he recalled the Christmas dinner for 550 Canadian men at the Rheinhotel in Godesberg, not even two months after the Armistice. An orchestra was engaged to play during the festivities, but the soldiers noted that the accompaniment was at best desultory. “We must forgive them for not being very happy about their erstwhile enemy coming in to conquer their country,” wrote George. “We didn’t blame them. Our crossing the lordly Rhine, their own their beloved Rhine, how could they be happy about it? So on neither side did we feel like singing ‘Joy to the world, the Lord is come’, and let us be fair about it, they didn’t feel like giving us a great hand of welcome either.” And having written of the jaunty departure from Godesberg, he wrote something that called the term friendship into question. “I think there was very little sincere friendship on either side. We are their victors and no friendship could cancel the fact, so it was not real friendship—they must be good to us—and it paid us to be good to them because we got well cared for—good billets and a fairly good time.” Even with Gerda, he spoke of the “complex problem” of a man’s heart, capable as it is of “containing a good many things at a time,” paramount among them the contradiction of loving an enemy.

Such reflections punch through the stock language in which he frequently cast his experience. The cheery send-offs, the parade of good hearts, can make a reader worry that George is reading off a script prepared by his culture. Yet, if that is so, it was an alternative script to the one being read by the men who commanded the forces then occupying Germany. Their script continued to vilify Germans, and theirs was the spirit that dominated the peace settlement concluded at Versailles later in 1919. And George’s optimism and openness toward the Germans he encountered was contrary to the anti-German mood in Canada, a hostility that lingered for years. Without doubt, he accepted a familiar dichotomy between people in the abstract and people in the concrete, growing to like individuals even as he remained reserved toward the group. Nonetheless, his diaries chronicle interactions that quickly allayed the fears that roiled him as he entered the defeated land.

George made the voyage home not on the Olympic, but on the Belgic, another ship of the White Star Line refitted as a troop carrier. The war had, if only temporarily, cramped the cosmopolitan style of first class on such vessels, their luxury trappings toned down to make room for more troops—all passengers in steerage. It was not clear George would ever return to Europe. He did not become a world traveler in subsequent years. His modest work as a Protestant minister on the Canadian prairie precluded that. But the experience in Europe, not just the war years but also their aftermath, transformed him, in an unspectacular way, into a cosmopolitan in spirit if not in body. He made it back to Europe, finally, in 1973, accompanied by one of his grown sons to visit the battlefields of his youth. And he spent several days in Godesberg with Gerda, just as respectful of her honor as ever. She still answered to the name Schmetterling.

Family stories shape us. The many hours I spent listening to my grandfather’s tales of the Great War initiated me into my vocation as a historian. Remarks on his months in Germany were sparser than accounts of horses and battles. In any case, the latter were more likely to impress a child. It was only years later, as an adult, that I explored his diaries and learned more about his time in the defeated land. With age has come a suspicion that this part of his experience ultimately had the deepest impact on me. His openness and curiosity, even his lifelong tendency—evident in his account of the war—to see himself as part of an epic, fed and fostered my cosmopolitan imagination when I chose a life that has taken me far from my home. It has been a life that has led me to foreign languages and years spent in Berlin, London, and Paris, as well as Toronto, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. I like to think I have become a citizen of the world. My own cosmopolitanism is a product of will, fueled by aspiration and conviction, in a sense by a philosophy of life. Nonetheless, I owe a debt to the less reflective but profound transformation wrought upon George by circumstances of fate and necessity.