Saul and the Witch of Endor, by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, 1526. Rijksmuseum.

Elizabeth I turned sixty in September 1593—old by anyone’s standards at the time. No other Tudor monarch had reached that number. Following this important birthday, she celebrated her accession day with particular splendor. At Windsor, her thirty-five years on the throne were marked with “a great triumph” of plays, masques, and tournaments. There was, of course, no question that she should retire, although, as one contemporary observed, “this crown is not like to fall to the ground for want of heads that claim to wear it.” Soon, her subjects would proudly boast that she was “that good old princess the now queen, the eldest prince in years and reign throughout Europe or our known world.”

In an age when men and women were expected to work until they could not physically do so, Elizabeth was doing nothing unusual in retaining her firm grasp on affairs. At the other end of the social scale, as in the poorest streets of Norwich in 1570, the elderly were also often active, but through necessity. A widow named Elizabeth Menson had lived in the town for forty years by 1570 and claimed to be eighty years old. She was “a lame woman of one hand,” perhaps having suffered a stroke; but she was still able to eke out a living with her spinning. She could also wind wool for money with one hand.

Eighty-year-old Alice Cotton, who was also lame in one hand, similarly spun for a living, as did Katherine Brand, another eighty-year-old widow, who could no longer walk. The even older Janice House, at eighty-five, had lived in the town all her life; she, too, was still spinning wool to support herself. They were lucky that their advanced years and illnesses did not prevent them from making a living. Many were not so fortunate and had to throw themselves on charity. A widowed contemporary, Erne Stowe, also “lame in her arm,” lived with an eleven-year-old boy, “a bastard of her daughter’s,” and the pair went about the town begging for aid. Agnes Durant, who claimed to be eighty-four in 1570, could no longer spin cloth for a living, and in her ill health relied on her daughter and eight-year-old granddaughter, both of whom had taken her place at the spinning wheel. The family were very poor, earning only 2d a week.

For most in Tudor England, old age was synonymous with poverty. In Ipswich, a census of the poor in 1597 revealed that many of the destitute there were elderly. A visitor to the most crowded and impoverished streets of the city might meet Anne Jackson, a sixty-year-old widow, who lived alone and scratched a living by gathering rushes. There was Joan Browne, aged sixty-five, who survived by picking wool. Widow Carick, who was sixty, eked out a living, as did so many in the area, by spinning wool.

A number of elderly women in Ipswich also had to support their “impotent” husbands, including the wife of Old Frize, an eighty-year-old ex-cobbler. She spun wool to keep the roof over their heads and food on the table. Cicely Sharpling, at sixty, was already “impotent” herself, trying to stretch her 8d in poor relief to survive, when she really needed a shilling. Elderly couples could at least pool their resources. Thus, seventy-year-old George Bales still worked as a smith, while his sixty-three-year-old wife mended clothes. Eighty-six-year-old Thomas Smith and his seventy-year-old wife were “both impotent and lame,” but just able to spin and card wool for pennies (while their thirty-year-old child did the same). In their case, the family were considered deserving enough to receive 2 shillings a week towards their living from the charitable will trust of Henry Tooley, a wealthy town merchant.

Old age could be particularly hard on women. Contemporaries had only to consider the wildly popular Women’s Secrets to know that old women should be viewed with suspicion. Best keep these crones away from infants, cautioned the learned text, since they could “poison the eyes of children lying in their cradles by their glance.” All women were “entirely venomous,” readers were told, but in earlier years menstrual blood at least served to dilute these evil humors. With the onset of the menopause, the poison was left to stew fetid in the body, with the worst toxins escaping malignantly through wrinkled eyes. It was advisable to be wary of these spider-like old women, especially the poorer sort, who were worse than the rich thanks to a diet of “coarse food, which contributes to the poisonous matter.”

It is no surprise that old women, therefore, were disproportionately victims of the charge of witchcraft. In one case, on Sunday, August 15, 1574, two young Londoners, Agnes Briggs and Rachel Pinder, were taken to Paul’s Cross, where they gave penance and publicly admitted that they had pretended to be bewitched. Rachel, who was eleven years old, had been particularly artful, arching her back and vomiting out hair, feathers, and threads. Briggs, who had seen Pinder perform, had aped her; hiding pins and fabric in her cheeks before bringing them forth in feigned fits. Both had named “Old Joan” as the cause of their affliction—their neighbor, elderly Joan Thornton. She was fortunate that the girls’ duplicity was soon uncovered, though Briggs’s subsequent remorse and desire “to ask forgiveness of the said Joan Thornton” can have been little comfort.

A similar story was played out when young Thomas Darling fell ill after getting lost in Winsell Wood, Derbyshire, in 1596. After his urine was examined by a physician, the boy was questioned as to whether he could have been bewitched. It was possible, agreed the boy, who had then been vomiting and falling into fits for some days. He recalled that, while in the woods, he had come into a little coppice where “I met a little old woman; she had a gray gown with a black fringe about the cape, a broad rimmed hat, and three warts on her face.” He recognized her, he said, since he had seen her begging from door to door in the little town of Stapenhill. He had, he confessed, broken wind as he passed her, to which the old woman angrily responded: “Gyp with a mischief, and fart with a bell: I will go to Heaven, and thou shalt go to hell,” before going about her business. The remark, coupled with her old appearance, was enough to raise suspicions. The woman must be, said those around the boy, Elizabeth Wright, “the witch of Stapenhill.” No, said others, Elizabeth “went little abroad.” It was her daughter, Alice Gooderidge, who had hexed the boy.

Alice was herself almost sixty years old and poorly educated, proving unable to recite the Lord’s Prayer under stern questioning. She was brought at once to Thomas, who, on seeing her, “fell suddenly marvelously into a sore fit.” Suspicion was always likely to fall on elderly Alice and her ancient mother, for they had been held four or five times before on suspicion of witchcraft. For good measure, Alice’s husband and daughter, too, were arrested.

Elizabeth Wright, “the Witch of Stapenhill,” who must have been at least seventy-five, proved a particularly pitiable prisoner. It was universally believed that only the witch herself could relieve her victim, and thus the ancient woman was brought into Thomas’s house. “Alas that ever I was born, what shall I do,” cried Elizabeth at the door, but she was forced inside and induced to pray for him. Both she and her daughter were stripped and searched by a group of duly appointed women, “to see if they could find any such marks on them. As are usually found on witches.” Elizabeth—on whom blemishes and other scars were unsurprising, given her age—was found to have “behind her right shoulder a thing much like the udder of a ewe that giveth suck with two teats.” She had, as well, two “great warts” on her shoulders. She had been born with the “teats,” she insisted. Her daughter had, in desperation, attempted to cut warts from her belly on hearing that she would be searched. They found instead “a hole of the bigness of two pence, fresh and bloody.”

Under pressure, Alice confessed that on her way to buy eggs, “I met the boy in the wood, and he called me witch of Stapenhill.” She had then complained to him that “every boy does call me witch, but did I ever make your arse to itch?” After being subjected to threats, she confessed to bewitching the boy that day. Immured in Derby jail, the unfortunate woman died before she could be executed. Thomas Darling underwent an exorcism and was soon quite well.

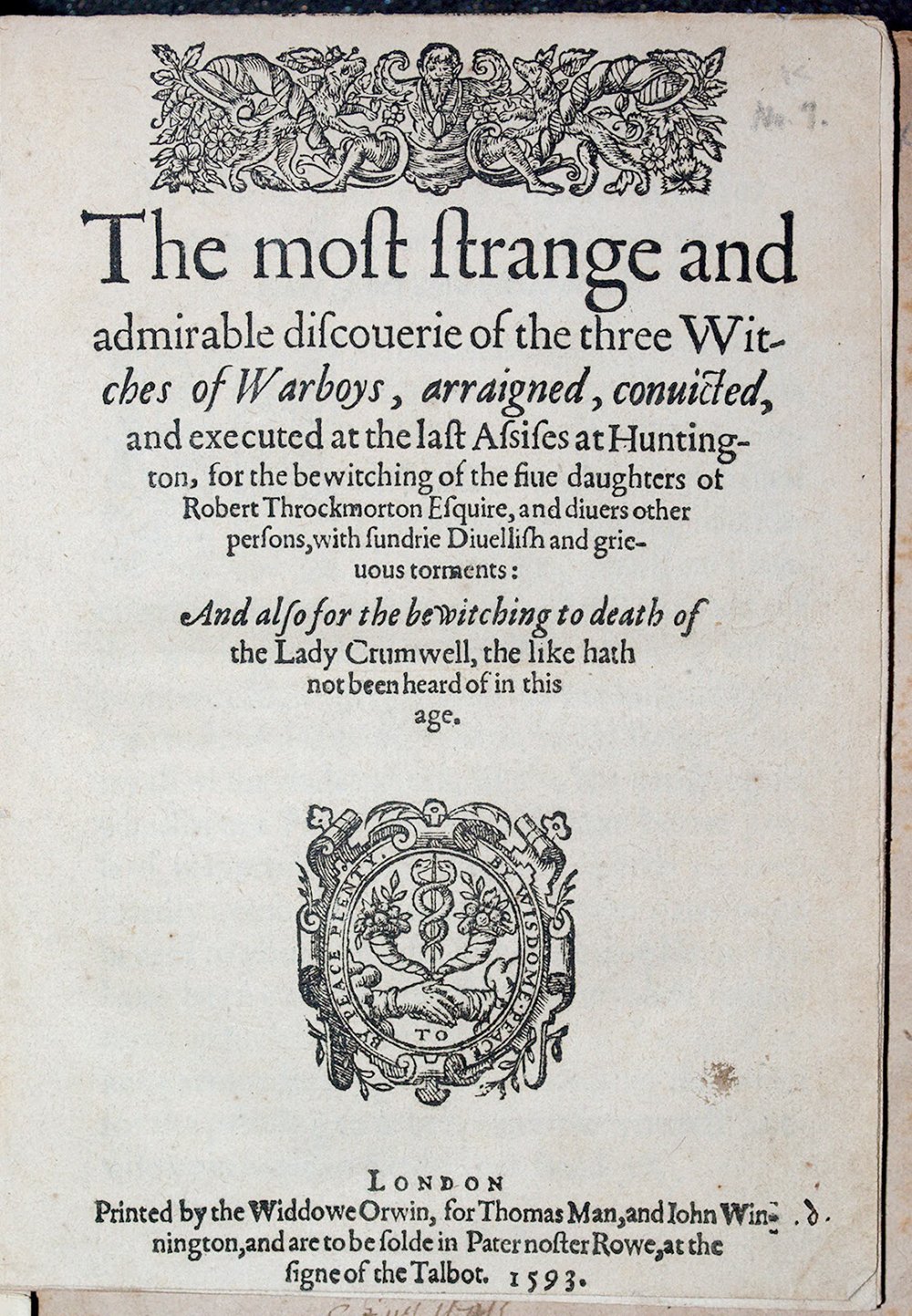

Elderly women such as Elizabeth Wright and Alice Gooderidge looked the part of witches and could do little to defend themselves against the rumors and accusations. They were far from alone. Witchcraft touched even the family of godly and practical Rose Hickman, when her five great-nieces suddenly gave every appearance of being possessed. These five Throckmorton girls had only recently moved into the manor house at Warboys, in Huntingdonshire, when around November 10, 1589, the second youngest—nine-year-old-Jane—fell ill. Her symptoms were strange, with sneezing fits signaling a fall into a trance. Then, her body would seem to swell and her legs shake violently, before the symptoms affected her arms and head. She stayed like this for two or three days, while curious neighbors came to see the strange sight and commiserate with the family.

One visitor was elderly Alice Samuel, smartly dressed in her black-fringed cap, who lived in the house next door. On entering the parlor, she had only just sat down when the girl cried out: “Grandmother, look where the old witch sits,” before pointing directly at her aged neighbor. “Did you ever see one more like a witch than she is?” the girl asked. Embarrassed, her mother rebuked her; but it was noted that Alice all the while sat still and silent. She looked “very rueful.”

Soon, all five of the Throckmorton girls, along with a number of the serving maids, were showing the same symptoms. All cried out against Alice, declaring: “Take her away. Look where she stands here before us in a black fringed cap,” even when she was not present; “it is she that has bewitched us, and she will kill us if you do not take her away.” At first, Mother Samuel had tried to be helpful, protesting that “she would come to the said children, whenever it pleased their parents to send for her, and that she would venture her life in water up to her chin, and lose some part of her best blood, to do them any good.”

However, when called for, her courage failed her, and she had to be forced, going “as willingly as a bear to the stake.” Once in her presence, the girls all predictably fell down, appearing “strangely tormented,” while Alice was forced to place her hand in Jane’s, as the girl scratched at it violently. It was, quite literally, a witch hunt, and when another neighbor, Lady Cromwell, fell ill and died after interrogating Alice, it seemed that Alice had added magical murder to her crimes. All Alice could say in her defense was that “Master Throckmorton and his wife did her great wrong, so to blame her without cause.” To Lady Cromwell, she had protested: “Madam, why do you use me thus? I never did you any harm as yet.” Nothing she said could have cleared her—she looked like a witch and everything she said seemed, to observers, to confirm her guilt. Finally, Alice, her husband John, and daughter Agnes were all imprisoned. In prison, old Mother Samuel appeared so unruly that she was chained to a bedpost. Under these conditions, she made a confession, but it was not enough to save either herself or her family. They were convicted and hanged in 1593. The Throckmorton girls recovered.

Excerpted from The Hidden Lives of Tudor Women: A Social History by Elizabeth Norton, published by Pegasus Books. Reprinted with permission. All other rights reserved.