Anatoly Liberman, courtesy of the College of Liberal Arts, University of Minnesota.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Anatoly Liberman is a tall man with a slight stoop and an accent that is hard to place. The stoop comes from decades spent searching for the hidden history of words in one of the fifteen languages he can read. It may also be from the weight bearing down on his shoulders as he races the clock. At the age of seventy-nine he is trying to finish one of the greatest achievements in the annals of lexicography: a history, as complete as possible, of some the last words in the English language whose origins remain unknown.

They are simple words, common words, but words whose origins are a mystery: he, she, girl, pimp, ever, gawk, yet. We use these words every day, but Liberman has been working for thirty years to unearth their roots. His sharp mind, breadth of language, and sense of mission have kept him moving steadily toward that goal for the last half of his life. He is driven by the knowledge that if he were gone, no one would have the depth of linguistic knowledge, let alone the drive, to complete his work.

The lilt in his voice, or the occasionally odd syntax, makes it clear Liberman is not from Minnesota, where he has lived since 1975, teaching in the department of German, Scandinavian, and Dutch at the University of Minnesota. Yet it’s impossible to tell where he is from without asking.

Liberman was born in Leningrad in 1937, the only son of Jewish parents. His mother was a music teacher and his father was an engineer. From a young age he loved books and novels and poetry—Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol. He studied English at school, listened to the BBC at night, and by the time he finished high school could read Dickens in English.

At university, Liberman added German, which he studied “very seriously and very systematically.” A few years later, he wrote his PhD dissertation on “Middle English Vowel Lengthening in Open Syllables.” In 1965 he joined a group at the Institute of Linguistics studying Scandinavian languages—first Icelandic, then Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish, and later early Germanic. By the early 1970s he had written the introduction and a line-by-line commentary for the first Russian translation of Beowulf; while the book was at the printer, he got permission from the Soviet authorities to emigrate to America as a Jewish refugee. After that, all references to Liberman were expunged from the Russian edition of Beowulf.

Thirty-eight years old, he got on a plane and flew to Minnesota with his wife and three-year-old son. The climate was similar to Russia’s, though the culture was not. Even so, he felt oddly at home and began publishing “like a house on fire,” as he says, while teaching, at various times, “Gothic, Old and Middle High German, Old Saxon, Middle Dutch, Old Frisian, and the entire Scandinavian cycle: Old Icelandic (with elements of Old Norwegian, Old Swedish, and Old Danish), Runic, and the skalds.”

In addition to the Russian, German, and English he speaks almost like a native, Liberman also knows Italian and Spanish and can “read practically” all the Germanic, Romance, and Slavic languages, leaving him uniquely placed to trace the origins of words that have been lost or never known. Many of those words come to him through chance, through serendipity, and through seeing things no one had noticed. Like pimp.

One day, Liberman was reading a German newspaper from the 1930s that used the word Pimpf to describe something like a pro-Nazi Boy Scouts, an organization that boys could join before they were old enough to join the Hitlerjugend.

“I thought it was a funny word,” Liberman says. “Almost like the English word pimp. And I thought, ‘What’s the origin of pimp?’ I looked it up, and all the dictionaries said only one thing: origin unknown. I said, ‘Well, these two words must be connected. It’s too good to be true that they’re not.’ So I began to read about pimp. And I began to read about Pimpf. And it turned out that pimp had many meanings totally unknown to me, like a menial worker in logging camps, and not only to do with prostitutes. That already is much closer to Pimpf.”

The worlds of English and German etymology were separate, so German scholars never heard the word pimp, and English scholars didn’t know Pimpf. “It was by chance that I ran into Pimpf and pimp and decided to connect them. And it turned out, of course, there was a connection.”

This kind of work can consume vast amounts of time, but it can also take you places you never expected. For example, in his research into pimp, Liberman found the word again in an English dialect, where it meant a bundle of wood.

“When I read that definition of pimp in the English dialect dictionary, I was struck almost speechless. What was the definition of pimp? It said, faggot. Now, the word faggot in its normal medium is a bundle of branches or twigs. I thought, dear me: pimp means faggot! What’s the definition of faggot, then? And that’s why I have the word faggot. Absolutely due to chance. That is what etymology is all about. One thread follows another.”

Not all of the words on Liberman’s dictionary are so colorful. But a few are.

“I was sick and tired of answering the question about the origin of fuck,” Liberman says. “So I thought one day I should investigate. But also it irritated me that the English dictionaries wrote that fuck is not connected with the German verb ficken. I knew it was nonsense. Such a coincidence was unthinkable. I decided to see what was known about ficken and what was known about fuck. A good deal is known about both of them.

“Another word I was sick and tired of answering questions about was cunt. I could not answer this question, so I thought, ‘I have answered fuck, now I will do cunt. Then they will leave me in peace.’”

Liberman has a sharp—and occasionally unorthodox—sense of humor (he once wrote a paper titled “Gone with the Wind: More Thoughts on Medieval Farting”) that belies the seriousness of his task. He was fully aware, when he began it in the 1980s, that it might take up take the rest of his life.

It was around 1985 when the idea first came to him, while he was looking into the origins of an Icelandic word heidrún, a term for a mythical goat whose milk is an endless stream of mead. He wondered if it might be related to the English word heifer, but when he looked it up, most of his numerous etymological dictionaries said simply: origin unknown.

For the next half a year, Liberman spent every minute he could trying to change that to origin known. By the time he had published his findings, he had found out that heidrún was related to the English haegfore, meaning the dweller of an enclosure. But a question had arisen in his mind: what other words had been orphaned like that?

Liberman knew he couldn’t spend half a year on each word and that there had to be a better way to account for them. Perhaps he could compile a dictionary of the words that had been lost or never found.

“Afterward,” he says, “I read the whole etymological dictionary and wrote all the words where it said origin unknown. Everybody asks the same thing: ‘You read the whole dictionary?’ And I say, ‘Well, yes. If you want to do something of this magnitude, you have to do it.’ ”

When Liberman finished compiling his list, he looked it over. There were about two thousand words on it. Many of them, like bobbish and bohunk, he knew would either be hopeless or not very enlightening. So he pared it down to around a thousand and began looking for ways to complete this work, to gather everything known about them.

Funding for this sort of project was sparse. Historical linguistics had gone out of fashion, replaced by structuralism and Chomskyanism. Still, he managed to get money to pay students to comb through all the old journals and magazines in English, page by page, volume by volume. They were publications from the 1800s and 1900s like The Academy, The Literary Gazette, and The Gentleman’s Magazine; regional publications like The Essex Review and The Cheshire Sheaf; and popular magazines like The Nation and The New Yorker.

“The New Yorker turned out to be useless,” says Liberman with a shrug. “But one had to do it to find that out.”

A few years later, when his money ran out, Liberman turned to volunteers and students to dig through old texts. Whenever one of them saw a note or article about any word on the list, it was photocopied and brought to Liberman, who decided if it might be of use. If so, he filed it accordingly. While they worked through the English-language journals, Liberman “skimmed three centuries’ worth of articles in every language I know and a few I don’t,” as he wrote in his book Word Origins.

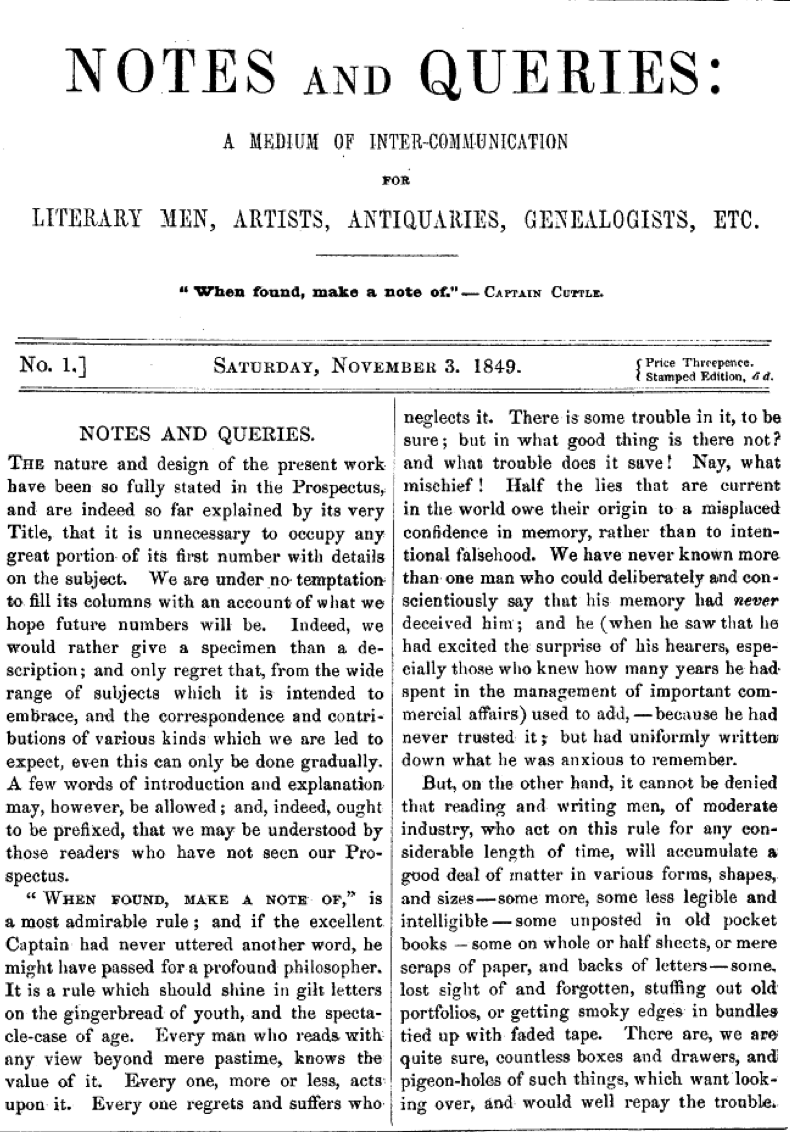

By far the best resource was a small journal called Notes and Queries, which was a kind of pre-electric, personalized search engine that started in 1849. Anyone with a question about anything would write in, and anyone who knew (or thought they knew) the answer could write back, with the answer appearing in later issues.

Inevitably, many people would wonder where words and phrases came from. When a reader wrote with a question, others answered, and still others wrote to correct those answers. From Notes and Queries, Liberman pulled 8,990 entries about word origins—fully a third of all the citations in his database. He also began collecting “all the editions of all the relevant dictionaries,” several hundred of which he Xeroxed.

The work was slow. The lifting was heavy. There were no shortcuts. Yet it had to be done. There was no way to automate it, because even though the project started before the Internet was born, the Internet turns out not to be useful for this kind of work.

“Can you do any searching with computers?” Liberman repeats the question in a resigned tone. “That’s what everybody asks. And, unfortunately, this answer is no. If you want to know the origin of a word, you will open the computer and Google the world heifer. Google will give you the titles of twenty etymological dictionaries, which is a waste to me. I have them all on my shelf. I know much more than a Google search, because I have every edition of every dictionary. I don’t need that. Sometimes Google Books will highlight a page, including Notes and Queries, that will show me something I may not know. But this is not even for dessert. These are crumbs.”

The meat of his findings turned up in strange places, like an article on French slang, or on laryngeals, or on German, Frisian, Dutch or Hittite. For words like hockey, tennis, and golf, he had to look through journals related to those sports. Casting such an enormous net is something few etymologists have time for.

By the end, he had gathered files on some 16,611 words that might contain some strand of meaning in the web he was weaving around his words. These were culled from 23,835 publications in twenty different languages. Today the folders line a wall in his office, standing on their side, packed in a shelf with their subject written on the tab in Liberman’s neat hand: Buggy, Bigot, Bodkin, Butterfly. In 2008, he published a small sample of these word histories under the title An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction, which included words like brain, cub, ivy, key, kick, man, oat, rabbit, slang, and witch. But there were still many more threads to be followed.

To get a sense of what this research entailed, I offered to be one of Liberman’s volunteers. By that time most of the entries for specific words has been collected, but he also wanted to harvest the proverbs discussed in Notes and Queries, because something useful might turn up.

I descended into the cramped basement stacks of the Wilson Library, a lifeless concrete cube on the University of Minnesota campus, and pulled the first volume of Notes and Queries off the shelf. The volume appeared in November 1849.

Readers queried about “deer-stealing” in Shakespeare, about where the Duke of Monmouth had been captured, about Madoc’s expedition to America. In the index I found references to the proverbs, “As Morse caught the Mare,” “Bishop has put his foot in it,” and “Humble Pie.”

“As Morse caught the Mare” was never answered. “Bishop has put his foot in it” was what people said when they burned food (alluding to the Church’s penchant for burning heretics). And “Humble Pie” was said to come from the humiliation of eating a pie made of “umbles,” or deer entrails.

The diction was strange, the phrasing formal and arcane, the work tedious. Sometimes it was hard to extract meaning from the notes or queries. But after some time, I could feel the rhythm of the old writing, and the voices began to come alive. They were erudite, thoughtful, lucid, and passionate.

A series of feisty exchanges about the phrase “Mind your Ps and Qs” first suggested that it referred to barkeeps keeping track of customers’ pints and quarts. Another writer said it came from barbers, who said, “Mind your toupees and queues,” meaning the artificial hairs on top and the pigtails in back. And yet another correspondent said it came from printers, whose apprentices often had trouble discriminating between p and q.

In this way, the modern wireless world slipped away, and I found myself lost in sixteenth-century England, where peasants were allowed to collect branches in the king’s wood “by hooke or crooke,” meaning the low, dead branches and wood on the forest floor that could be gathered with a hook or a staff, rather than by damaging the trees.

Often I would forget where I was. It was like time travel, and I could see how a person could spend a lifetime running down such holes, chasing the meanings of words as far as possible, until the voices went silent, and you reached the end, until there was nothing more.

After I was done with the first volume, I copied the relevant pages and sent off my packet to Liberman. A week or so later, he followed up with a stern bullet-pointed email, informing me that he was “not interested in Latin and Greek (or French) proverbs and quotations,” “so-called familiar quotations (from Goldsmith, Shakespeare—really or presumably) are not needed either,” and “if possible, don’t diminish the pages beyond 93 percent.”

At the end, he added, “I have weeded out all the pages that cover 1–3, above, and the residue is small, so at the moment there is no urgent need to meet. Thank you very much!”

Residue. There was a sting to the word, as if I had let him down, and let history down. Somehow I had failed to discern linguistic gold from sand. In time, though, I began to see that this was more a matter of Slavic bluntness, of efficiency, and of a man who doesn’t have time or money to waste. Because while he does not seem rushed, he is racing in advance of the wheel of time.

The sting subsided, though, and I returned to the library, paging through more volumes, listening in on lost conversations. For nearly a year, I went back to the library every month or so. By the time I reached the twelfth (and final) volume in the first “series” of Notes and Queries, I had an idea of the countless hours of labor that must go into something like this. Later I asked Liberman what he loved about etymology.

“Love is the wrong word,” he says. “Etymology is not a child or a woman. So there is nothing to love it for. It’s the excitement of discovery. Whether you discover a new particle in physics or the origin of a word, it’s really the same thing. It’s the excitement of the chase, the hunter’s feeling that you had your prey, and that you succeeded!”

It’s a pleasure heightened further by the joy of saving things from history. “One of the great things I am doing,” Liberman tells me, “is that I will return from oblivion so many works and so many names that deserve recognition.”

Take dwarf, which Liberman considers one of his crowning achievements. For over a century, everyone in the English-speaking world believed it was a word carried over from Indo-European. But Liberman knew that every Germanic language except Gothic had a related word, like dwerg and dwaas, which means things like foolish or crazy.

One day, Liberman was looking at an 1884 edition of Friedrich Kluge’s Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (he has all twenty-four editions) when he saw something incredible. Kluge had made the same connection, tracing dwarf to a Germanic origin, but in later editions gave it up for the more popular Indo-European theory. Suddenly, Liberman knew he had made a great rediscovery.

“When I saw Kluge’s dwesk,” he wrote, “everything in my ideas about Germanic dwarves fell into place. According to the most ancient beliefs, supernatural beings brought on diseases. Language has retained many traces of those superstitions: god is related to giddy, elfshot means lumbago (cf. OE ylfen ‘raving mad’), and troll, most likely, has the same root as droll. The dwarves, before they became anthropomorphic, must have shared their evil power with the gods, elves, and trolls.”

Such are the joys of discovery, of the chase, of words, and of tracing their threads back through time. It’s what makes this work so exciting and so important. It reminds us that we are the last link in a chain that reaches further back than we can see or remember or imagine. These words are a window into worlds that have vanished but to which we remain connected. They let us hear the voices of those who came before us, whose words and ideas and beliefs lurk in our minds even today.

Now, in his seventy-ninth year, the hard work, the thousand of hours of sifting through old texts and papers, is done. The 16,611 words sit in their folders on his shelves, and his A–B volume is nearly ready to be published.

But Liberman is restless. He still has a full teaching load. He still has many other projects (and ideas for more) beside his dictionary. He recently translated Shakespeare’s sonnets into Russian. He has nearly finished a book on Old Icelandic. He writes a weekly blog for Oxford University Press. He appears regularly on a local radio show to talk about etymology. And now he also plans to publish a book on the origins of idioms, which would be the first of its kind.

“If I get all the other projects off my back, then it goes fast,” Liberman says. “One can write a couple letters in a year. All the bibliographies, all the research, all the reading, everything has been done. The whole project, if I really worked on it incessantly, would take five or six years. Everything is here. It’s only a matter of reading.”

But whether Liberman goes down in history as a kind of etymological George R.R. Martin who may or may not live long enough to complete his life’s work, or as one of the great etymologists of all time, remains to be seen.

“Much depends on my longevity,” Liberman says. “I project everything as though I were going to live forever. If I kick the bucket tomorrow, none of those books will be published. But the projects keep me on my toes. It would be a pity to die before completing them, but I feel young and full of pep. So what will happen tomorrow, or five years from now, one never knows.”