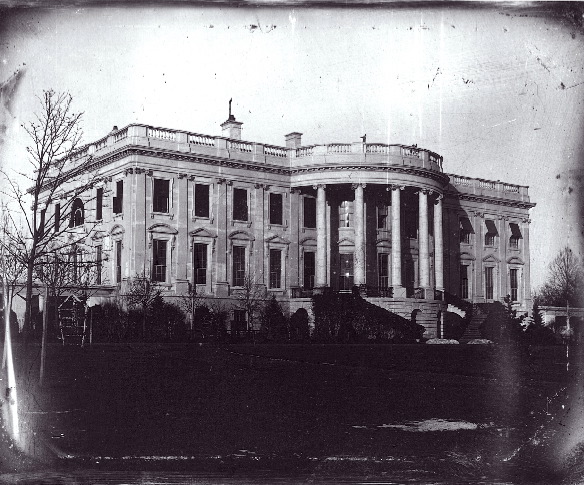

An 1846 daguerrotype of the White House.

President Donald Trump is learning that life in the White House isn’t as easy as life in Trump Tower. For one, the New York Times reported this week that he’s been spending a lot of time exploring his new Washington, DC, home in his bathrobe—there are, one can imagine, many parts of the White House to get lost in. For another, his staff is having a hard time figuring out how to turn on the lights in meeting rooms.

We at Lapham’s Quarterly are here to help. Over the years we’ve published quite a few accounts of what life in the White House looks and feels like, and here are some of the most useful.

In our Home issue, Abigail Adams arrived at the White House in 1800 and was less than impressed—she, too, had trouble with the lighting situation.

The lighting of the apartments, from the kitchen to parlors and chambers, is a tax indeed; and the fires we are obliged to keep to secure us from daily agues is another very cheering comfort. To assist us in this great castle, and render less attendance necessary, bells are wholly wanting, not one single one being hung through the whole house, and promises are all you can obtain. This is so great an inconvenience that I know not what to do, or how to do.

In “Working the Room,” an essay in Politics, Michael Phillips Anderson considers how funny a president should be.

During his presidency, Lincoln suffered from depression, deepened by the deaths of his mother and older sister and by the Civil War. He tried to keep his darker moods out of public view, leading even his most dedicated supporters such as Richard Henry Dana to wonder, “Can this man Lincoln ever be serious?” When asked how he liked being president, Lincoln replied jokingly, and honestly, “You have heard the story, haven’t you, about the man who was tarred and feathered and carried out of town on a rail? A man in the crowd asked him how he liked it. His reply was that if it was not for the honor of the thing, he would much rather walk.”

In “First Ladies-in-Waiting,” we learn that more than one president found himself without a First Lady to manage the increasingly complicated White House social scene.

The First Lady’s every move is watched by both the political and celebrity press; her conversation skills are cited as key to the president’s hosting of foreign dignitaries, and countless blogs devoted to her sartorial choices parse the underlying meaning of cardigan versus jacket at public appearances. The First Lady—whose title is widely acknowledged as having been initially bestowed upon Lucy Webb Hayes, wife of Rutherford B. Hayes, though it is used retroactively to discuss prior holders of the job—is an indispensible part of any presidential administration, and yet the president’s having of a wife was not always something to be counted upon.

Harry Truman, in our Comedy issue, considered the different kinds of aides a president might need.

I have appointed a Secretary for Columnists. His duties are to listen to all radio commentators, read all columnists in the newspapers from ivory tower to lowest gossip, coordinate them, and give me the result so I can run the United States and the world as it should be. I have several able men in reserve besides the present holder of the job, because I think in a week or two, the present Secretary for Columnists will need the services of a psychiatrist and will in all probability end up in St. Elizabeth’s.

And finally, from Magic Shows: a séance in the home of the First Family.

At a seance in the White House in 1862, Nettie Colburn Maynard, the medium, recalled that, after losing consciousness, she, channeling Daniel Webster, spoke for over an hour, during which President Abraham Lincoln was assured that the Emancipation Proclamation he had written but not signed would be “the crowning event of his administration and life” and that he needed to “stand firm” against dissenters. Arthur Conan Doyle later speculated that it “may have been one of the most important [moments] in the history of the United States.”