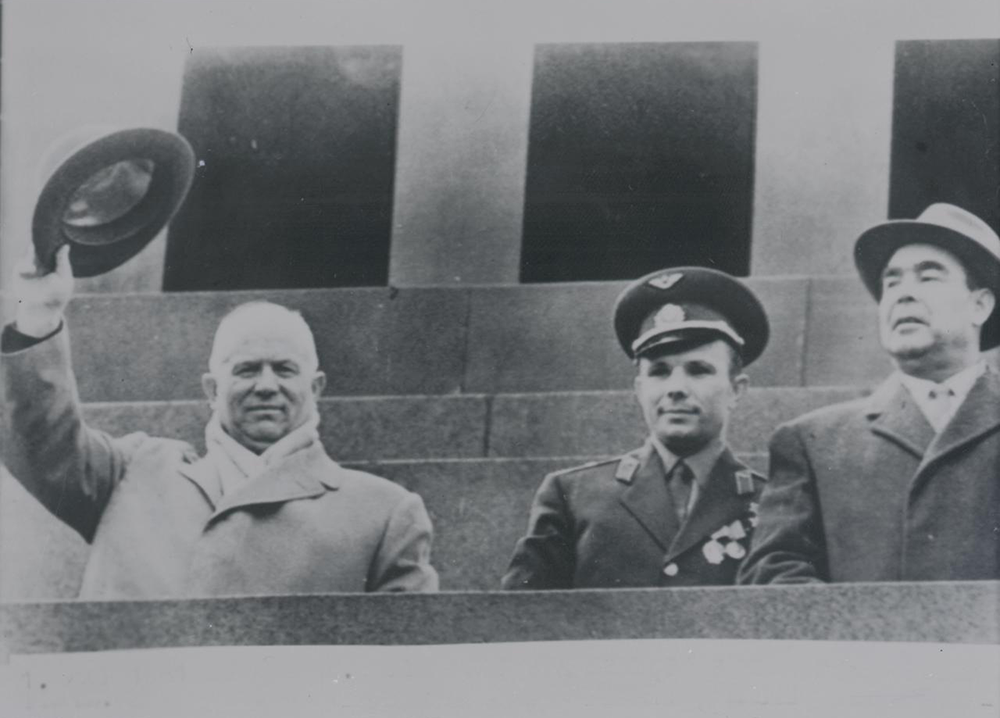

Premier Nikita Khrushchev and Vice President Richard Nixon on TV at the opening of the American National Exhibition, Moscow, 1959. Photograph by Thomas J. O’Halloran. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

In the spring of 1970, at his dacha outside Moscow, Nikita Khrushchev posed for a series of seemingly silly photographs. Seated on a bench, Khrushchev alternated between two wide-brimmed hats atop his plump head while son Sergei snapped the shots. In the background, his wife Nina Khrushcheva scolded her seventy-four-year-old husband for the childish prank: “Surely you don’t intend to wear them,” she said. “They’re too bright.” Khrushcheva was right. The man who once went toe to toe with John F. Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis didn’t intend to wear them, but a group of American editors needed the photographs as a sign to proceed with what would come to be seen as an explosive and grand act of Cold War subterfuge: the publication of Nikita Khrushchev’s memoirs, against the wishes of the Soviet leadership. The Americans called it the Jones Project.

Sergei Khrushchev comes to the door in a nearly transparent short-sleeved white button-down shirt. He’s still buttoning as he greets me. He has lived in the U.S. since 1991, and I met him once before, perhaps fifteen years ago, when he gave a lecture in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He was about sixty-five at the time, and the resemblance to his father was striking. Today he is older than Khrushchev the elder was when he died at seventy-seven; looking at him is like staring at an alternative version of the past. I visit him at his home in a small middle-class suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, where he was a senior fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

There are few formalities. We don’t drink tea; he doesn’t ask me about my train ride. Instead we immediately sit at the table and begin talking. Sergei has written many books about his father—whom he calls simply Khrushchev—and it is clear that he defends his father’s legacy with ardor and views him as the inheritor of a noble if thinly populated tradition. Three times during our conversation he compared his father either to reforming tsars or to Leon Trotsky. He reminds me of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin: accent thick (as though his tongue is a herring trapped in cream sauce), bald pate, icy blue eyes.

“He wanted to tell the truth,” Sergei said—in particular, that “I lived through Stalin’s time. I changed my opinion about Stalin.” Khrushchev was under no illusions his memoirs could be published in the USSR. “Historically it was not in the Russian political culture when you lose power to write a memoir,” Sergei told me. Two powerful people had attempted it. One was Sergei Witte, a prominent minister under the last two Russian tsars; his memoirs were written in secret, held in France during World War I for safekeeping, and published only posthumously, in the West. Sergei went on, “The second was unfortunately Leon Trotsky,” who was killed while in exile in Mexico on Stalin’s orders after writing several books critical of Stalin’s regime. He “paid dearly for it…And then it was Khrushchev.”

Nikita Khrushchev, who led the Soviet Union from 1953 until 1964 as first secretary of the Communist Party—and, from 1958 to 1964, as premier—is remembered in the West for his contradictions. The Ukraine-born former metalworker was known for a crass outburst at the UN, when he banged his shoe on the lectern; he and JFK nearly irradiated the world during their Cuban confrontation; he angered the intellectual class with his outbursts against “deviant” art, including at one Moscow exhibition where he called some of the abstract pieces “dog shit” and “art for donkeys,” asking the artists if they were “pederasts,” not painters. And yet Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev is also remembered for the so-called Secret Speech before the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1956. The speech began shortly after midnight. In front of the Politburo, Khrushchev carried on for four hours, listing some of Joseph Stalin’s crimes, “a whole series of exceedingly serious and grave perversions of party principles, of party democracy, of revolutionary legality,” as he called them. It was reported that some people in the hall were so sickened by what they heard they had to be carried out of the room. By the time he finished, it was clear that Khrushchev was taking control of the reins of power while changing the trajectory of the country. Khrushchev reigned as a solitary figure of power for the next eight years, carrying out partial reforms. His government granted posthumous rehabilitation to scores of people who had been executed or died in imprisoned ignominy; commuted the sentences of thousands of souls who had been sent to the gulag; and initiated the thaw that would liberalize, if at times haltingly, a superpower that had gone horribly wrong. The Soviet Union—one-sixth of the world—had terrorized its own citizens, uprooting and massacring tens of millions, cannibalizing its own economy, and becoming increasingly paranoid.

As one might expect, Khrushchev’s program of de-Stalinization had its opponents. By 1963 the Soviet economy was wobbling. Leonid Brezhnev, a high-ranking party member, masterminded a power grab, and Khrushchev was soon out of a job, lucky to escape with his life. In a made-for-television twist, Nina Khrushcheva and Viktoria Brezhneva were vacationing together in Czechoslovakia when the machinations were effected. William Taubman, Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer of Khrushchev, wrote that someone called Brezhnev’s wife at the resort to report the successful capture of power but didn’t realize that it was Khrushchev’s wife who picked up the phone. As he related the details, he caught on that he had the wrong listener only when the woman on the other end remained silent.

Two years later, Khrushchev was living a remarkably ordinary life, puttering around his garden like the average Moscow pensioner, albeit one in a deep depression. When a schoolmaster asked his grandson what the former premier was up to, the boy replied, “Grandfather cries.”

His family convinced him to begin recording his memories—it would be useful to history, to the country, to the party, to have the thoughts and reflections of a former leader, they told him, and it would give him a purpose, a reason to get up in the morning. It would also allow Khrushchev to tell his side of the story. With his name essentially forbidden from being uttered on the radio or in newspapers, Khrushchev was, politically speaking, a nonperson. He could also show how the current leadership was undoing some of his most hard-won accomplishments. (Even politically erased, he still could get under Brezhnev’s skin: he liked to report that Brezhnev’s visceral hatred of him ran so deep that once, as the leader was passing a Crimean village called Nikita, he ordered its name changed.)

Khrushchev began recording his memories on a German-made Uher recorder in 1966, doing so not in any organized fashion but piece by piece, event by event, at his dacha in Petrovo-Dalneye. He recorded over 250 hours of tape, putting in three to five hours of work per day. At first he would dictate only while taking walks, often with friends, where he could escape the bugs the KGB had planted inside his home—lugging the nearly ten-pound machine with him as he went. Soon, though, he gave up the ruse and became comfortable recording in his living room—it wouldn’t be the first time he’d delivered a speech before an unsympathetic audience. Khrushchev was a naturally gregarious man, and with an interlocutor the ebb and flow of conversation brought back memories more easily to him. Eventually, Sergei hired a typist to transcribe the tapes and arranged the typescript into a chronological and cohesive narrative. The complete manuscript ran to some 1,500 pages.

As Sergei writes in an afterword to the first volume of his father’s memoirs, when Brezhnev got wind of the project—which the Khrushchevs weren’t keeping secret anyway—he was terrified about what it might reveal about himself and summoned Khrushchev to the Central Committee headquarters. Because of his intense hatred of the man who had preceded him in power, or perhaps out of cowardice, Brezhnev wouldn’t confront his predecessor. He instead commissioned his deputies to convince Khrushchev to give up the project. Khrushchev refused, insisting that as a private citizen he had a right to write his memoirs, and that they would benefit the entire country, party and public alike. His position was consistent with steps he took as premier. It was under Khrushchev in the late 1950s that former prisoners in Stalin’s camps, now rehabilitated by the state, were encouraged to write memoirs and provide their own view of that era. Their documentation of the gross injustices—torture, ethnic groups deported from ancestral homelands and imprisoned en masse—was a direct rebuttal to the cult of Stalin.

Of course, Khrushchev’s argument for his rights as a private citizen didn’t persuade the powers at hand. They wanted him to cease writing his memoirs, period. Both father and son knew they needed an emergency plan to prevent the KGB from confiscating the documents and tapes and erasing the memoirs for good. One evening, Sergei attended a party at the home of a man named Victor Louis. Louis lived in unheard-of opulence for the USSR at that time: at his three-story dacha in the Peredelkino neighborhood he kept several cars, among them a Bentley and a Mercedes, and had his own tennis court. He also had a private swimming pool—the only one, he claimed, in the entire Soviet Union.

Louis had spent eight years in a prison camp on political charges. While there, he had a reputation among fellow prisoners as dangerous and among authorities as useful—in other words, he was a stool pigeon. Upon his rehabilitation, he married a British woman and became the Russian correspondent for the British newspaper the Evening News. If authorities wanted to float sensitive stories or test ideas, Louis got the scoop for the English-language papers. As Sergei described him, Louis “didn’t work for the KGB, he worked with the KGB. He was an unofficial voice in some very controversial aspects of international relations.” It was Louis who broke the news of Khrushchev’s ouster from power in 1964. Louis’ life remains shrouded in mystery and oddity. He translated My Fair Lady into Russian and kept all the royalties, and he once published an interview with Alexander Solzhenitsyn that Solzhenitsyn claimed never took place. But he appears to have been so successful as an operator that neither the Brits nor the Soviets could afford not to have him working for them. And he was no inexperienced dealmaker: with a wink from the Soviet “organs” in power, he accompanied dissident Valery Tarsis when Tarsis defected in London and arranged to have Tarsis’ memoirs published there, too. The Soviets hoped that Tarsis—who had been imprisoned in a psych ward in the USSR for “unhealthy” political views (a common Soviet tactic of branding dissidents as psychopaths)—would come off so strange that his memoir would be discredited. Louis pulled off the job and pocketed Tarsis’ entire book advance. He had also peddled to U.S. publishers a doctored version of the memoirs of Svetlana Alliluyeva, Joseph Stalin’s daughter. Alliluyeva had defected from the USSR in 1967, and she was planning on publishing her memoir in the fall of that year to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the October Revolution. Louis wanted the unauthorized and doctored version to appear a few months earlier, presenting a less critical version of Alliluyeva’s memoirs and preempting any uproar over the book before the festivities rolled around.

Sergei Khrushchev didn’t know any of this, and he was in a tight corner. He knew enough (or perhaps too little) to realize that Louis could get the manuscript published abroad. He wasn’t concerned about making money. For the son, this was a chance to vindicate the father, and Victor Louis could pull it off. Sergei Khrushchev gave him a copy of the tapes and the massive manuscript, with the understanding that Louis would start discussions with U.S. publishers but would have to wait for Sergei’s go-ahead in order to actually do anything. Publication abroad was a step both father and son hoped they wouldn’t have to take, since it would inevitably be seen as an anti-Soviet act, and Khrushchev was far from disavowing the system he once led. If he was anti-anything, it was anti-Brezhnev. Disillusioned by the pressure placed on him by the KGB to stop writing, Khrushchev had warmed to the idea that if Brezhnev and his cronies ever attempted to seize the manuscript, then the book should appear in the West. Yet back in 1957, at the beginning of Khrushchev’s time in power, he had punished Boris Pasternak for doing essentially the same thing. Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago was printed in the West when the Soviets blocked its publication in Russia. Pasternak was pilloried by both fellow writers and the authorities and was forced to decline the 1958 Nobel Prize in Literature. After reading Doctor Zhivago in retirement, Khrushchev admitted, “We shouldn’t have banned it. I should have read it myself. There’s nothing anti-Soviet in it.” He felt the same about his own work.

Meanwhile, Louis had already gotten in touch with Jerrold Schecter, the Moscow bureau chief for Time Inc. First Louis fed Schecter a red herring—he offered the memoirs of diplomat and politician Vyacheslav Molotov, a Stalin protégé. Schecter took the bait, but Louis told him to hang tight. “A few weeks later he said, ‘Well, I think I could work with you. What I told you about Molotov’s memoirs isn’t around Moscow and obviously you can keep a secret,’” Schecter told me when we spoke on the phone. Then Louis offered him Khrushchev’s memoirs instead. Schecter said, “Sure, that’s even better.” Soon Schecter visited Louis’ dacha, where he listened to a few minutes of tape. The voice was unmistakable: it was Khrushchev talking.

But Time Inc.,which was going to run excerpts in Life, and its subsidiary, Little, Brown—which was going to publish the book—wanted more proof. They knew that some would claim Schecter had been fooled, that this was a KGB plot, the memoirs were a forgery, and Louis was a Soviet plant. They got a few tapes from Louis and took them to a voice recognition lab in New Jersey. There was no doubt: the voice prints were a match for Khrushchev.

Now Schecter needed to find a translator. While staying at the Connaught Hotel in London to meet with Louis and arrange the details of the advance, he invited Strobe Talbott, a young Rhodes scholar who had done a little freelance translation for Schecter in Moscow one summer. Talbott’s roommate in Oxford was a fellow Rhodes scholar, a young Arkansan named Bill Clinton. Years later, Talbott served as deputy secretary of state in his old roommate’s administration; now he’s the head of the Brookings Institution. Back then, Talbott was working on a dissertation on the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. He had no idea what awaited him when he checked into his room at the discreet hotel. Carrying a briefcase, Schecter knocked on the door and asked for a précis of the unwieldy pile of papers inside it by that evening. After ten hours of reading, Talbott emerged with a summary of the manuscript that blew Schecter and the editors from Time Inc. and Little, Brown away. Talbott, only twenty-three at the time, was hired to translate it.

When I spoke with Talbott and Schecter on the phone, I asked Talbott if he’d realized the gravitas of the project. “Goddamn right,” he said. “I was ten years old when Khrushchev rolled the tanks into Budapest and slaughtered the Hungarian freedom fighters. I was eleven years old when he sent Sputnik up and sent us all into outer space ourselves with fear. I was sixteen in 1962 when he brought us to the brink of thermonuclear war.”

As the translation progressed and Talbott asked to listen to the tapes himself in places where the manuscript wasn’t clear, he encountered hysterical resistance from Louis, who had refused to let the remaining tapes out of his hands. “I began to appreciate that for him a business negotiation was an exercise in histrionics,” Talbott wrote at the time in his personal diary. “His petulance was fine-tuned to transmit just a hint of threat that he might walk out at any moment.” The contract negotiations were still under way—Louis wanted (and ultimately got) a high six-figure advance, which he again kept for himself—and he was using the tapes as a bargaining chip. Plus, he claimed he was worried about his own safety: should the Soviet authorities discover his role in the publication of Khrushchev’s memoirs, they might take drastic action. Perhaps even for Victor Louis—a seemingly untouchable figure who operated in a swampland of political intrigue, greed, and double-crossing—this was a bridge too far.

Meanwhile, Nikita Khrushchev had suffered a serious heart attack. He was convalescing in the Kremlin hospital when Sergei was called into the KGB’s Moscow headquarters in the infamous Lubyanka building. The officials went straight to the point: They wanted the tapes. They wanted the manuscript. One of the agents casually mentioned that they’d already collected a copy of the manuscript from the typist. They knew Sergei had the original. What seems certain is that they didn’t know Victor Louis also had the pages and a set of tapes.

Sergei had known for some time he was under KGB surveillance, but in the meeting he acted the naïf. “I was scared, but not as much as I showed—and I gave them everything.” The agents accompanied him home, where he retrieved the original recordings and the typescript. He returned to the headquarters and signed those materials over for “safekeeping,” knowing as he took the official receipt listing what had been collected that he’d never see the originals again. He did not tell them about the copies in possession of Louis—and, by then, of the editors at Time Inc. and Little, Brown, too.

At that point, Sergei Khrushchev knew he had to pull the trigger. He gave Louis permission to publish the manuscript abroad, fully aware that in the current environment the memoirs couldn’t be published in Russian. He knew the KGB’s advantage rested upon possessing all the tapes. The official organs of the Soviet Union were hardly likely to take reprisals against such public figures as the former premier and his family, especially, as Sergei reasoned, with the whole world watching. “If it was published, you can do nothing,” he told me. But he had to make the harrowing decision alone. His father was in a delicate state, and the doctors had warned against agitating him. It was, Sergei recalls, one of the most difficult decisions of his life, and he has doubts about it to this day. His father ought to have been the one to make the decision to relinquish the originals, not him.

Louis and Schecter wrangled over how the memoir would be presented in the United States. The Khrushchev family wanted no official ties to the book’s publication. Instead it would be billed as the unauthorized remembrances of Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev and his family could claim, in a half-truth, to have been ignorant of how the book made its way west, since they were unaware of the specifics of Louis’ dealings with Little, Brown, or even how he transported the tapes and manuscript overseas. Yet Schecter required a sign from Nikita Khrushchev himself that he was involved with the plans for the memoirs and had agreed to their publication. The last thing the Time editor wanted was for the book to come out and then have Khrushchev issue a statement claiming that the words were not his own, that the entire thing was a forgery, a CIA ruse. So he gave Louis two hats and asked for photographs of Khrushchev wearing them. They would be, in Schecter’s words, “confirmation that the special pensioner was in on the project.”

In November, only three months after the KGB thought they had confiscated the only two existing versions of the manuscript—the original and the typist’s copy—Little, Brown announced the forthcoming publication of Khrushchev Remembers. Sergei’s thinking was correct: there was very little the authorities could do at that point. A frail Khrushchev was called into the Central Committee one more time so that Brezhnev’s deputies could give a dying man a humiliating dressing-down. Sergei suffered no severe repercussions, protected by the fact that he’d turned over all the tapes in his possession to the KGB. He claimed he didn’t know how the tapes had made their way to the West, and in a sense he wasn’t lying—Louis hadn’t shared any specifics with him. The memoirs became both a New York Times bestseller and a feather in the cap for the United States during an era of intense propaganda. Not only was the publication proof of a repressive regime willing to silence its own former leaders, it also showed how a sinister enemy had been outfoxed. The book put Khrushchev’s name back in the spotlight at a time when the two nations were experiencing renewed tensions.

Khrushchev lived to see the publication of the first of two volumes, though it was a bittersweet experience for a man who’d been ensconced in party politics since 1921 and was now in the cold. When Sergei brought a copy of the book, with Khrushchev’s picture on the cover, to his father’s bedside, the reaction was subdued. “He leafed through it, looked at the photograph, and handed it back to me.”

Khrushchev died in 1971. His funeral was quiet, and the authorities unsuccessfully attempted to prevent any graveside speeches. Among the few who did speak, Sergei talked about his father primarily as a family man. There was no elaborate graveside memorial. Years later, the sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, at the family’s request, crafted a headstone for the grave, slabs of interlocking yet not quite perfectly fitted black and white marble. A bust of Khrushchev, either grimacing or slightly smiling, peers out from a gap in the stone, looking as though he’s a prisoner of the dark and the light. Neizvestny had been among the artists Khrushchev had excoriated for their anti-Soviet art, yet the sculptor recognized in Khrushchev a captain who attempted, if inconsistently and ultimately unsuccessfully, to right a sinking ship. He said the work was intended to depict the dualism inside Khrushchev’s soul. Or, as Talbott told me, the former leader of the Soviet Union “had some sense that the system was a disaster.”

Nikita Khrushchev didn’t live to see his memoirs published in Russian. They first began to appear in the glasnost era, but were available in full only after the Soviet system had entirely collapsed. The work that might have been a clarion call to save the system became a eulogy instead. As I sit across the table from Sergei, he tells me, almost in a lament, of his father’s one regret about the entire affair: “He did not read English. For him the book remained alien. If only it had been a Soviet book.”