La Sortie de l’opéra en l’an 2000 (People Leaving the Opera in the Year 2000), by Albert Robida, c. 1902. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Landauer Collection of Aeronautical Prints and Drawings.

We see those who created versions of the future in the early modern age in terms of adornments; a steampunk sky scattered with retrofitted airships, Tesla towers, and the ornamental addition of goggles and clockwork mechanisms to already largely fictive Victoriana. It is pantomime fashion and though fun in a tribal sense, it pales in comparison to the actual futurism of the time.

In France, the devastating social indictments of Victor Hugo and Émile Zola were joined by images of what could be when—as seemed inevitable to progressives—the rotten present was replaced. It was a profound critical and appreciative knowledge of the past and present that informed Albert Robida’s visions of a future Paris. Far from the merely ornamental, Robida built a vast three-dimensional world in his trilogy The Twentieth Century (1883), War in the Twentieth Century (1887), and The Electric Life (1892). Set in the far-flung 1950s, these are prophetic in terms of the real world and the future of futurology. He envisaged a tunnel under the sea linking France and England. He predicted the creation of man-made continents reclaimed from the sea (à la Atlantropa, the plans to drain the East and Hudson Rivers in New York and the reclamation of Doggerland by means of a ninety-foot-high Atlantic dam). He correctly envisaged cities growing skyward, even if the predicted levitating aerocabs, aerobuses, hot-air balloons, and zeppelins with docking stations on the tops of buildings (Paris’ Central Station atop Notre Dame cathedral) have remained elusive. As too has the ability to manipulate the weather and the mechanics of the solar system.

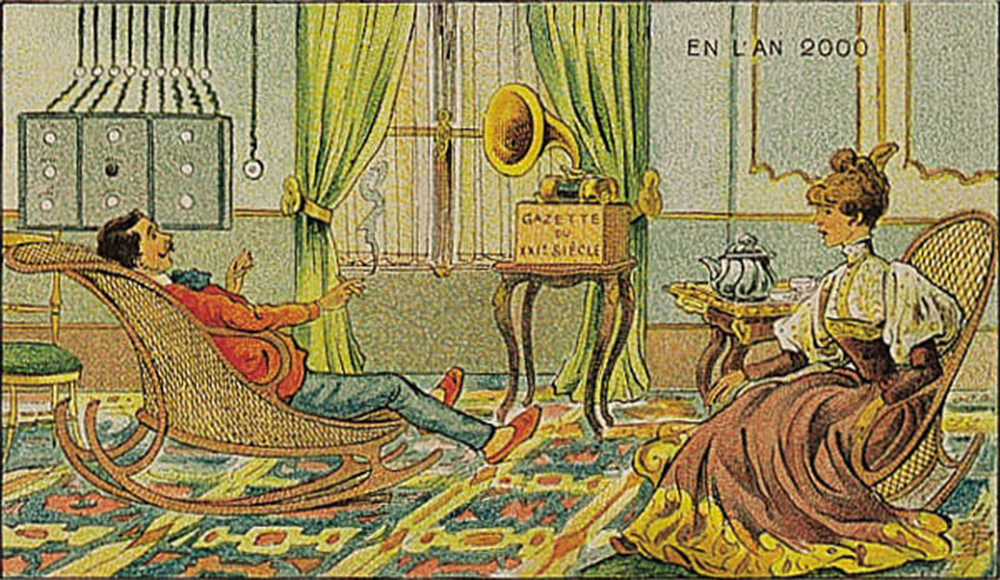

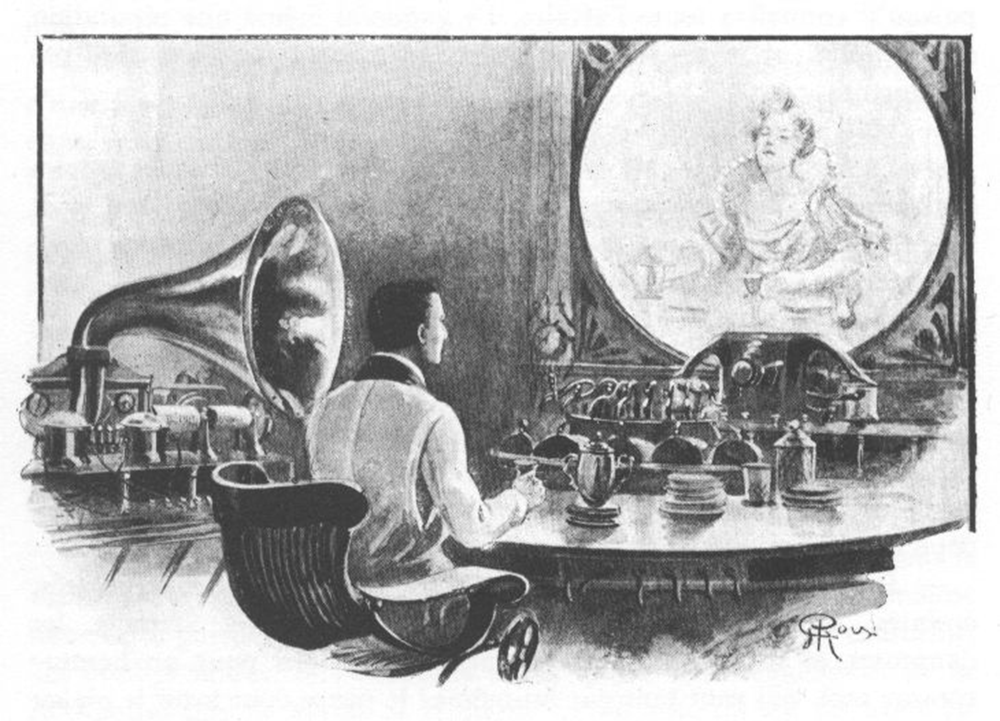

There were accurate predictions; women are more emancipated though insufficiently so, food is mass produced, advertisements have colonized public space (in Tony Garnier’s Cité Industrielle, instead of ads on facades there were utopian excerpts from Zola’s Travail and Saint Simon). There are approximations of television, telephones, computers, and the internet. Robida gets the substance right and the surface wrong. Despite being mid-twentieth century, his characters are manifestly fin de siècle in appearance; the women are frilly art nouveau ladies, the men top-hat-wearing bearded gentlemen. He forgets that the very definition of fashion is that it changes.

Yet this failure is one of the more endearing aspects to Robida’s work; it is a charming time-capsule future. At its best, it is a thing of flamboyant splendor; in his romantic vision of a future Paris skyline at night, flying machines with headlights for eyes are piloted, with a ship’s wheel, through a fog that seems almost submarine. The rich glide through the moonlight, the police watch over the city by the light of an artificial star. We are crucially high enough above the glittering electric lights of the streets to imagine that all is safe and serene.

Robida was unique but not alone. Across the English Channel, William Heath etched a strange early nineteenth-century view of the future. His Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK) lampoons technological advances with an apparatus-filled structure emblazoned “Acme of Human Invention. Grand Servant Superseding Apparatus for Doing Every Kind of Household Work.” The emerging globalized consumer culture was mocked with the ad “Patent Fire: Fresh imported from the interior of Mount Etna.” Technology that emerges after our youth always seems alien. Heath sketches, with incredulity, fantastical satires of his present: a pneumatic tube delivering people directly to Bengal, a bat-winged postal worker, “the steam horse Velocity,” a black mechanical bat taking convicts to New South Wales, a series of castles in the sky labeled sardonically “march of the intellect.” Heath manages a final sarcastic riposte in the title, though it is the lament of the powerless, Canute staring at a tide of time, “Lord how this world improves as we get older.”

Technology impacts not just directly but as side effect. In The Aerial Burglar by Percival Leigh, people “were favored with a peep into futurity” by means of mesmerism. In their visions, mankind had conquered the skies by the year 2000, with floating islands filled with cats and bathed in artificial daylight. Crime had however “soared into the sky; and theft and robbery contaminated the air.” As a consequence air police were required, with steam-powered vehicles “in the form of birds or of fishes, others resembled dragons, griffins, and other fabulous animals.” It did not end well for one fleeing thief. A policeman “drawing an electrical blunderbuss…discharged a flash of lightning at his guilty head…His hat, singed and blazing, flew to the winds, and his blackened and shattered form fell, with innumerable gyrations to earth.”

As much as the apocalypse industry proves perennially lucrative, sometimes pessimistic predictions are received with hostility. During economic boom, such are the invincible halcyon delusions that questioning voices are treated as treasonous. In 1989, a long-locked Parisian safe was seared open with a blowtorch. A manuscript was found inside, titled Paris in the Twentieth Century. It had been placed there over a century earlier. The tale was by Jules Verne. It had been rejected by the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel, who dissuaded Verne from writing such gloomy improbable visions of the future (the 1960s) in favor of sticking to rip-roaring adventures that were advertisements for the age (“Is Five Weeks in a Balloon a reality or is it not?”) rather than dissuasions. It will be unbelievable, claimed Hetzel, failing to realize that no one would believe the actual 1960s either.

Verne’s predictions are intriguing for their accuracy and the reasons behind their inaccuracies. Often it seems that his time has not yet come. His hydrogen-powered cars, magnetic and pneumatic trains, and synthetic foods seem perpetually imminent even if the latter is not extracted from coal as foretold. The man-made climate change he predicted is under way, and his unholy alliance of corporations and the state prevails. Verne’s assertion that culture would be controlled under a state bureaucracy seems an accurate reflection of the totalitarian regimes that would follow, while the dumbed-down entertainment-producing committees seem reminiscent of everything from sitcoms to tabloids. The belief that music would become a cacophony was somewhat realized, though harmony has survived. Verne failed to see that art would endure and indeed thrive, due to its role as an ever-inflating investment bubble. His claim that there would be no news seems naive given that we are conversely swamped by it daily, just as we are with the images he imagined would be telegraphically passed around the world. Technology has made the threat of extinction a possibility and also locked adversaries into positions of mutually assured destruction. Verne predicted both. The electric chair he foresaw has come and gone and may well come again. Indeed all surveys of prophecies are incomplete as time refuses to pause.

Verne’s most precise prophecies are observations that were just as true in his day. His protagonist is an artist who finds himself adrift and ridiculed in a world dictated by commerce and mercilessly formalist sciences (Verne had been pressured by his father into law and finance against his calling). Poetry is reduced to mechanical treatises, though Verne fails to see the evident appeal in tomes such as Meditations on Oxygen and Decarbonated Odes. The protagonist ends up with his tears frozen to the graveside of De Musset. The old writer famously wrote in L’Orfèvre, Lorenzaccio, “Great artists have no country,” which was as much a lament of creative exile (as obvious here) as it was an internationalist boast. Verne was voicing the unease of the dandy, who fears beauty will be abolished in the name of function and who defends the sanctity of art as defiantly, exquisitely useless (as Wilde and Ruskin did).

Verne knew the character of his age and how it would pan out. Others focused on the gadgets, the dazzling conveniences, and proved Verne’s fears of a tyranny of utility to be correct. These accounts, with their shopping lists of inventions, say more than they seem to, by omission and implication; a world where nothing else is needed or required and so real human concerns are silently excised, a world where those reporting unwanted side effects and consequences are the problem and not the issues themselves. Verne wrote another vision of the future (or purloined one from his son Michel). “In the Year 2889” provides a glimpse of future cities:

with populations amounting sometimes to 10,000,000 souls; their streets 300 feet wide, their houses 1,000 feet in height; with a temperature the same in all seasons; with their lines of aerial locomotion crossing the sky in every direction!… Think of the railroads of the olden time, and you will be able to appreciate the pneumatic tubes through which today one travels at the rate of 1,000 miles an hour.

There is an approximation of atomic power in the far-reaching inventions (the transformer and accumulator) of Joseph Jackson, the star inventor in the story, which extract energy from the sun’s rays and convert it to virtually any purpose. As much as nuclear power has been revolutionary (for good and ill), the evasiveness of the cold fusion adds disappointment to Verne’s claim that “they have put into the hands of man a power that is almost infinite” (“almost infinite” being an impossibility especially apt to futurology).

In this vision, Centropolis has usurped Washington, DC, as the political capital of the U.S. Newspapers come in audio form. Advertisements are projected onto clouds. Air is “nutritive.” Convenience has reached the stage of mechanical servants. “Why, Doctor, as you well know, everything is done by machinery here. It is not for me to go to the bath; the bath will come to me.” Verne is self-deprecatingly satirical, with his “hall of the novel-writers, a vast apartment crowned with an enormous transparent cupola. In one corner is a telephone, through which a hundred Earth Chronicle littérateurs in turn recount to the public in daily installments a hundred novels.” Information and its flow are critical, an accurate prophecy of the modern age. Verne pictures an eminent figure in a single day discussing signals of revolution on Jupiter, changing the borders of Europe, donating money to prospective innovators (one who wishes to engineer a synthetic human, another who is developing a transportable city), inspecting a vast array of accounts, visiting an electricity works at Niagara and undergoing a health check. Data would set us free, a message we still hear from Smart City and Internet of Things evangelists today, with little acknowledgment that it is what we do with the data that counts, who can access it, and for what purpose.

Verne and Robida’s visions move us, in part because of what they did not see on the horizon, namely the First World War, the cataclysm of which makes the world of the late nineteenth century seem almost mythic. Theirs is a world of style, daring, and chivalry (however idealized), which they were careful to retain, a world of evening wear and impeccable manners, architecture and machinery with a sensuality of form and florid embellishment. That this world was a largely illusory one accessible only to a privileged few does not matter. Perhaps they envisaged eventually an aristocratic life for all but visions can well be delusions. In La Caricature, Robida had ridiculed those modernist city planners pursuing the “holy straight line,” mocking the “patron saint of the good city, ideal of picturesque beauty, light of the magistrates, star of local councils! Cut, destroy, erase, rake, scrap, trench, align in the name of the very holy straight line and create the modern style, the grand, delicious, superb style of the nineteenth century, or cretinal flamboyant.”

Robida was worried that all sense of humanity would be lost in inhuman architecture and technology, not realizing that the organic too was artifice. We could not lose what we did not possess to begin with.

Reprinted with permission from Imaginary Cities: A Tour of Dream Cities, Nightmare Cities, and Everywhere in Between by Darran Anderson. Published by the University of Chicago Press in the United States/Influx Press in the United Kingdom. © 2015 Darran Anderson. All rights reserved.

Explore the Lapham’s Quarterly issue The Future.