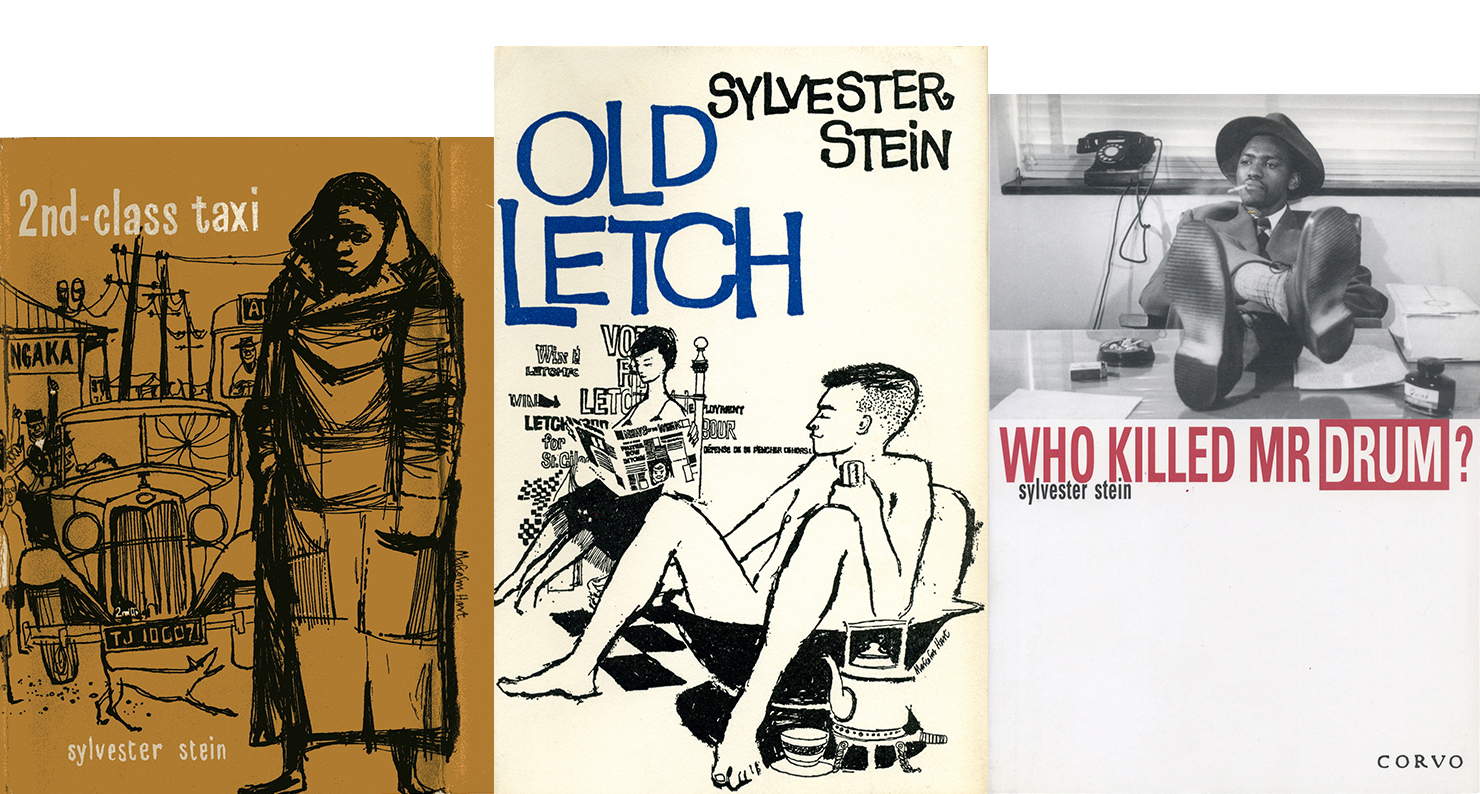

Covers of Sylvester Stein’s novels Second-Class Taxi (1958) and Old Letch (1959) and memoir Who Killed Mr. Drum? (1999). Courtesy of Sarah Cawkwell.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

When I met Sylvester Stein, I had no idea who he was, aside from my landlord. I stayed in the grand Victorian townhouse on Highbury hill where he and his third wife, the artist Sarah Cawkwell, lived. I was in and out of London researching a colonial history set in the British West Indies, and I constantly saw the city as if through a thin sheet of parchment, the kind used in scrapbooks to protect old photographs. If I lifted the semitransparent layer, every corner revealed its past. I kept imagining the Edwardian-era servants who must have slept in the basement, as I did in the summer of 2009. Whenever I walked past a fireman-red clock tower nearby, a memorial to Queen Victoria, it suggested empire. The name of an adjacent street recalled the grove where plantation owners whom I was pursuing in archives once lived.

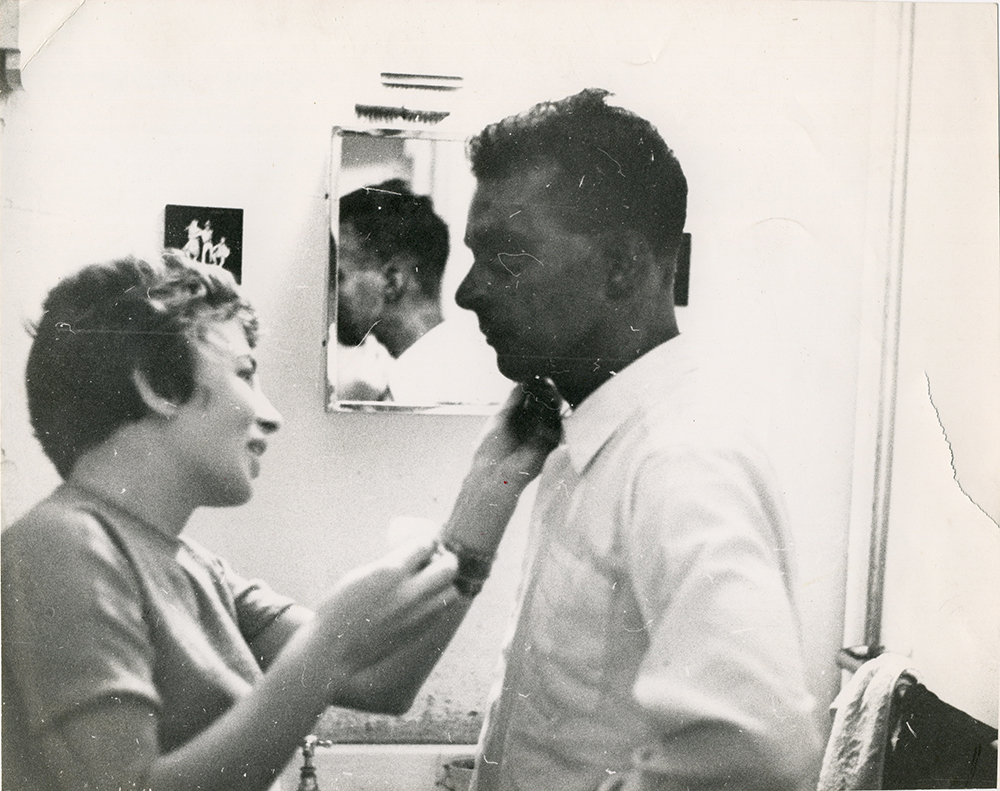

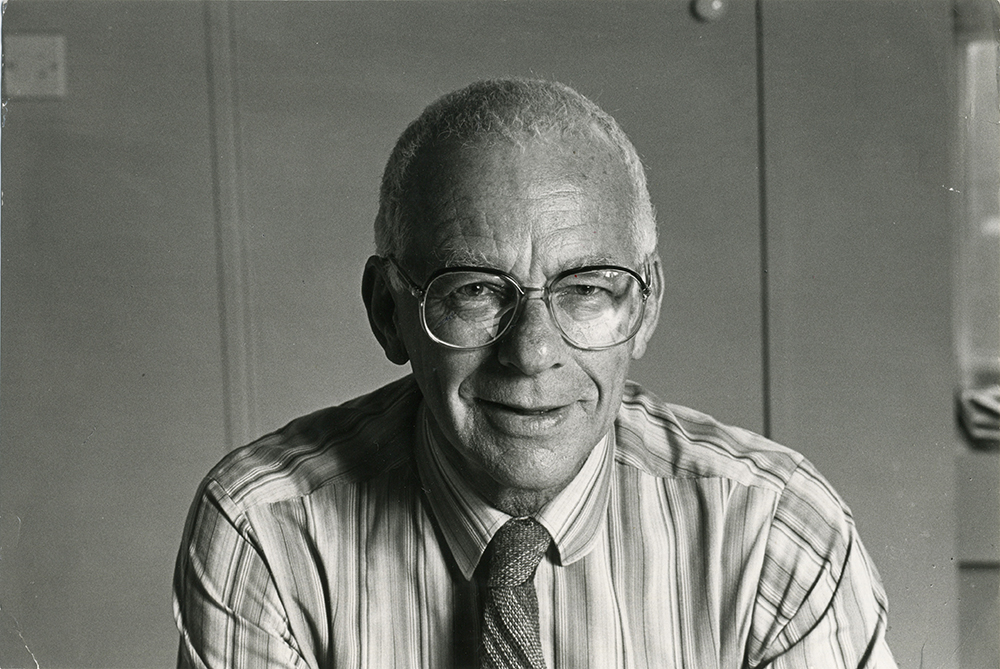

I chatted with Sarah sometimes, but Sylvester was remote to me. He was the octogenarian I occasionally glimpsed in the garden. In early 2011, when I shared an entrance to the house with the couple, Sarah asked that I not linger on floors other than the attic I rented because my presence might startle him. By then, Sylvester had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. The few times I did run into him, I had to remind him I was the lodger.

Once, when we all sat down to dinner together—our one formal date during that trip—he told me, repeating the title of a memoir he had penned a few years earlier, before his memory had started to ebb, “I danced with Mrs. Gandhi.” He had waltzed with the future Indian prime minister when she briefly stopped in South Africa on her way home from England during World War II. I realized then that I should have been pulling back the parchment to see more clearly the silver-haired man with roguish blue eyes in front of me, a journalist and writer whose contributions to the arc of history had been significant.

Yet in both his birthplace, South Africa, and his adopted home, Britain, public memory of him has faded—perhaps because the offbeat humor that characterizes his literary work was an odd match for the darkly serious political subjects he tackled. Sylvester died a relatively forgotten figure in London last Christmas, a few days after turning ninety-five. In the end, his memory played self-annihilating tricks on him. Slowly, he lost grasp of the details of his own legacy: as a comic novelist whose debut, a satirical romp about apartheid, was banned in South Africa the day it was published and as an editor of the storied anti-apartheid magazine Drum during its golden age.

Drum was part of a postwar flowering of publications (some CIA-funded, often a secret even to their editors) on Cold War battlegrounds from India to Latin America. Founded in 1951 as African Drum by white South Africans, the magazine at first alienated the black audience it targeted. Under its founding editor, cricketer Bob Crisp, it delivered patronizing pieces on tribal history and traditions in a feature titled “Know Yourselves.” Circulation languished as potential readers spurned this condescending approach. One said in a focus group, “Chiefs! We don’t care about chiefs!” Another pronounced, “Drum’s what white men want Africans to be, not what they are.” The second editor, Englishman and Shakespeare scholar Anthony Sampson, had never met an African person before turning up at the magazine. He had attended Oxford with Drum’s publisher and cofounder Jim Bailey, the younger son of a South African gold mining magnate. In his memoir, Sampson said he had to overcome rumors that the magazine was “a white propaganda sheet” run by the Chamber of Mines or the Colonial Office.

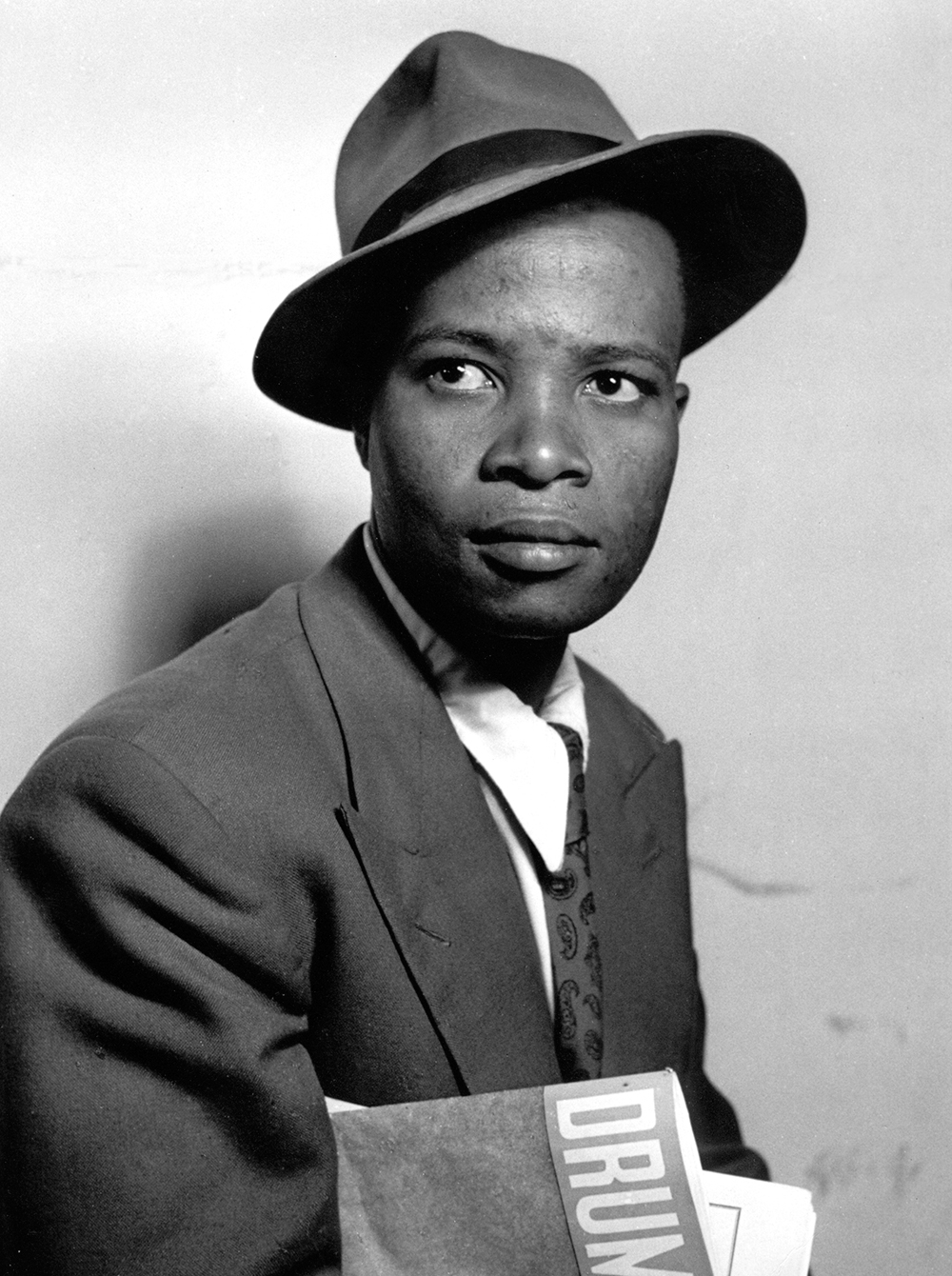

Yet over the next decade, the monthly magazine (which soon dropped “African” from its name) evolved into the voice of urbanized, cosmopolitan blacks in South Africa—a voice speaking brash English, its slang Americanized, its rhythms jazz-inflected, its attitude cheeky, and its reach extending outside the continent to the world at large. As early as 1952, Time called it “the leading spokesman for South Africa’s 9,000,000 African and Coloured populations.” Investigative reporting that was the first to illuminate the injustices of apartheid helped win the magazine its reputation. Star reporter Henry Nxumalo went undercover on a Boer potato farm where black laborers, coerced into exploitative contracts, had for years been flogged, handcuffed, and sometimes even killed. He then got himself arrested for walking the streets without a pass after curfew in order to document conditions in an infamous Johannesburg jail. Under the anonymous byline Mr. Drum, he also exposed sugar estates that trapped Indian workers into child labor and debt peonage and vineyards that paid their Coloured workers only in wine.

The magazine had styled itself as a rambunctious township rag reveling in sport, jazz, crime stories, slick ads, and sexy pinups. Its irreverence wasn’t meant to be directly political, but it couldn’t brand itself a black magazine in South Africa in the 1950s and not contend with politics. Government authorities had become increasingly repressive, and the African National Congress and more radical political parties responded with increasing confrontation. Simply by reporting on events, Drum regularly rattled apartheid’s architects and enforcers, including the police, the Nationalist Party, and the Dutch Reformed Church.

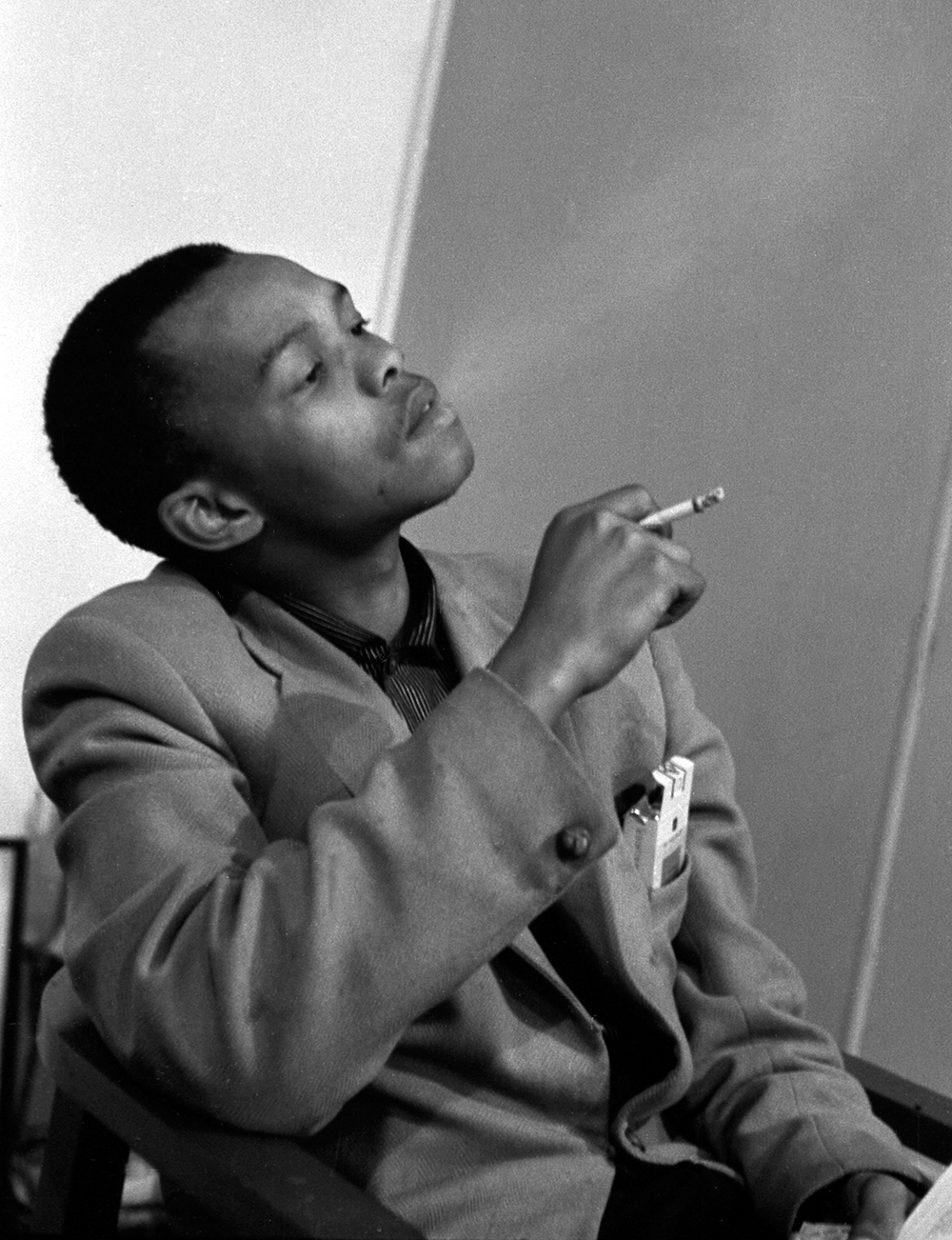

The magazine that Stein inherited in 1955 was, in his words, a “mighty little urchin.” Its music critic Todd Matshikiza, a jazz composer and pianist, was already writing reviews in his infectious, inimitable style: King Force the saxophonist “gulps giggle water by the gallon and makes greater and greater sounds with every additional drop.” Can Themba, a schoolteacher who was hired after winning Drum’s annual short story contest, was already crafting the brilliantly sardonic prose that later marked him as a forebear of the New Journalists.

Into the rumpus came Stein, nudging the magazine into a crusading role, encouraging his reporters to continue taking risks. He assigned one to sit in the pews of several whites-only churches to provoke (and photograph) a reaction. Under Stein Drum took an overt stance on racial equality in sports. He oversaw a page-one Mr. Drum feature calling for the inclusion of blacks on South Africa’s Olympic team, and his staff helped organize a delegation to FIFA to advocate for black representation on South Africa’s soccer team.

The magazine became more image-driven under his successor Tom Hopkinson, another Oxford man brought out from England and a former editor of Picture Post who redesigned Drum to resemble that revered photo magazine. Today much of Drum’s reputation rests on the brave, sensitive documentary photography produced by Jürgen Schadeberg, Bob Gosani, Ernest Cole, and others. This gifted group provided the definitive, iconic images of apartheid and the struggle against it, which were globally syndicated and communicated the system’s horror to the world. The only photos of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, when police shot dead sixty-nine peaceful protesters, were taken by Ian Berry, a Drum photographer hired by Hopkinson.

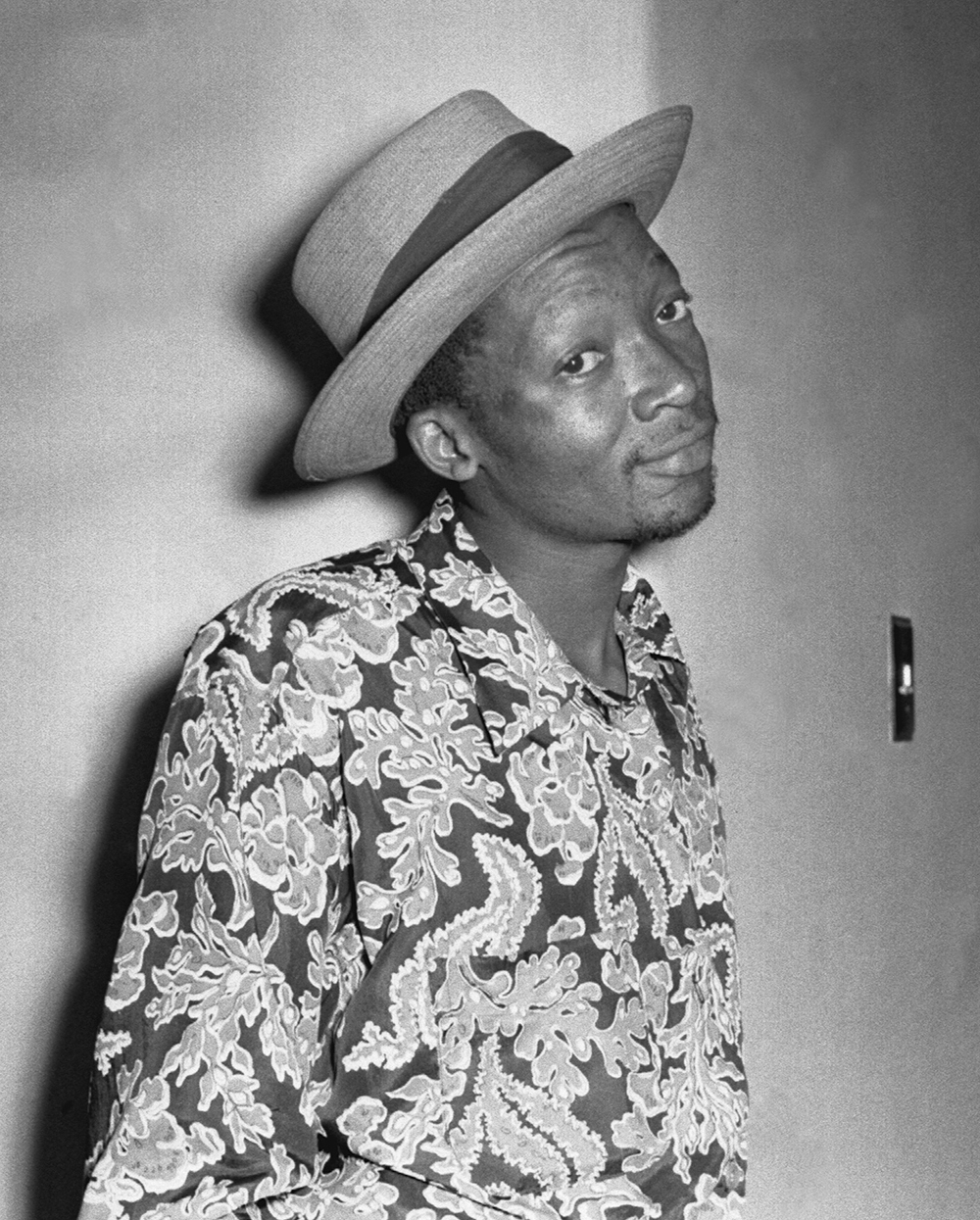

If Hopkinson’s era was distinguished by the photography and Sampson’s by the most audacious Mr. Drum exposés, then Stein’s own particular imprint was literary. He hired Es’kia Mphahlele, who later wrote the lauded novel The Wanderers, and made him fiction editor. With Mphahlele and Themba on staff and Stein at the helm, a crop of writers who went on to become some of South Africa’s most canonized were free to riff in an inventive, hybrid, syncopated style that came to be closely associated with Drum. They formed what was known as the Sophiatown Renaissance, named for the black township closest to Johannesburg that was a hub of black intellectual, cultural, and social life.

Of the three editors who presided during Drum’s most daring decade, the 1950s, Stein was the only South African. He nonetheless was conscious, then and in retrospect, that he was still a white man in charge of a mostly black staff. In the 1999 memoir Who Killed Mr. Drum?, he expressed some anxiety that Themba, perhaps expecting to be editor-in-chief himself, might resent Stein as no more than a figurehead. He joked that his true job was dealing with the white pressmen, who wouldn’t have accepted orders from a black journalist. He was aware that his staff, navigating a society that required them to perform the role of “good native,” probably also did so with him and Bailey. “Deep down maybe they cursed us, together with the whole white race, and deep down we recognized it,” Stein wrote.

He once had his face painted with permanganate to pass as Indian in Sophiatown, then filed a report for the BBC on the experience. He had been to gangster-filled shebeens before, of course, but had never felt as imperiled there as he was “without the natural protection that my white skin would have given me,” he wrote in Who Killed Mr. Drum?. Yet in borrowed skin, he felt he “could converse at ease with my constituents, without their being defensive before a lani, a white man.” Stein had worked as a stage actor in London for two years after being demobilized from the navy at the end of World War II. Whether the exercise of an actor or an undercover journalist, Stein’s use of brownface unsettles—but for him it was an attempt at empathy. In Who Killed Mr. Drum?, he explained that “to go native in that way, I believed, would help me to feel my way into the black skin that my colleagues and my readers lived in permanently.”

He considered himself an outsider, too. Roughly 45,000 Jews, as many as who went to Palestine, emigrated from Russia to South Africa. His grandparents were part of that exodus. In the 1890s, Stein’s grandfather Schlomo Stein escaped as a stowaway in the funnel of a ship. He earned the bribes needed to smuggle his family out of Lithuania by working as a peddler and an ostrich farmer in the Cape. Stein’s father had no schooling except in the Talmud before arriving in South Africa at nine years old but went on to become a professor. His mother was a baby when her family fled Eastern Europe, settling ultimately in Muizenberg, a beach resort and Jewish enclave known as “the shtetl by the sea”; she later helped resettle Jews in flight from the Nazis. When Stein was born, during a family holiday in 1920, his parents waited a month before sailing home rather than violate an Orthodox ban on travel immediately after childbirth. Their Jewish identity mattered to them.

It did to Stein as well, at least politically, shaping his leftist affiliations. He experienced anti-Semitism throughout his life. As a child in Durban, where his father taught university physics, he was subjected to slurs and once was hit “over the head with a knotted handkerchief…for crimes against Jesus Christ of long standing,” as he wrote in Who Killed Mr. Drum?. He explained, “When young, I gave no thought to blacks as a competing species. It was the Gentiles who were cast as the competing race.” As a young adult, Stein began to challenge the customary codes against interracial friendships. “We were growing up and there was no social mixing,” he told oral historian Louise Brodie in an interview. Later, when he was in college in the late 1930s, “Me and some of my friends, we decided to go and make friends with the Indians. They were down at the bottom of Natal. We went there. We managed to make a little social connection.”

Going brownface can be understood better in the context of this lifelong process of seeking connection, and it should perhaps be considered in the context of his family’s history in the Pale, the strictly defined geographical area to which Jews were restricted by law in tsarist Russia. The state regulated who belonged where by drawing lines on a map that couldn’t be crossed casually or legally, much as it did in South Africa. Under apartheid, Indians were barred from living in one province and from walking the pavements in another, while confined to ghettoes still elsewhere; and blacks and Coloured were restricted to separate townships, their presence in Johannesburg legitimate only by day and even then only as employees.

Stein argued that the discrimination South African Jews and their forebears had suffered led them to play a pivotal part in opposing apartheid, writing that they acted as a kind of “Trojan horse” in enjoying access to the ruling elite that allowed them to serve as go-betweens for nonwhites. He claimed that Jews were the whites who most frequently represented the African National Congress as lawyers, took stances against apartheid as journalists and academics, and provided funds and safe houses to the resistance. “They were or felt they were excluded from society, so they took up with this other lot who were excluded,” Stein told me the last time we met, a month before he died.

During Stein’s interviews with Brodie, archived at the British Library, he fitfully recalled his life with the frustration of a raconteur unable to summon relevant facts. He joined the military, he remembered, to escape either a girlfriend or his first wife—but couldn’t say which. Asked how he met the second of his three wives, he replied, rallying with a self-mocking spirit, “Yes, that’s a good story, if I can remember it. It’s one of my stories, but I’ve gone and forgot it.” Some details stubbornly stuck, but their context had receded. He knew he had once lived at 62 Regent’s Park Road, but couldn’t remember what country it was in. Was it South Africa? Or England? The memory persisted without a map.

Such lapses marred his final years. Sometimes he had no memory at all of writing his books. Cawkwell, who married Stein in 1985, was determined to ensure that others would not forget, even if he did. She built a website dedicated to his life and work and reissued his books in inexpensive floppy stapled editions under an imprint she created just for him, the Nononsense Press. In memoriam, she has set up a trust for journalists in South Africa.

Even before dementia’s onset, Stein felt mocked by the fallibility of memory, which exacerbated the creative toll that exile already takes. Decades earlier, he brooded over the fate of his friend Gerard Sekoto, a painter who continued to churn out portraits of his beloved South Africa while exiled in France but, as Stein lamented in Who Killed Mr Drum?, was “painting memories only, fading year by year, being copies of copies.” Stein, visiting him in Paris in the early 1960s, “saw the danger: his emotions were becoming memories of memories.”

Yet discrepancies between 2012’s I Danced with Mrs. Gandhi and 1999’s Who Killed Mr. Drum? suggest peril of another kind. Memory might become derivative with the distance of decades and oceans—or it might grow more vividly motley as the ties to its source loosened. One story Stein tells involves a horse-riding trip into landlocked Lesotho. Rapids from a storm wash away one of his riding party’s horses, its legs sticking up in the air, and delays Stein’s return home. In Who Killed Mr. Drum?, the delay means that Stein, then the political editor of the Rand Daily Mail, misses the phone call offering him the job of editor at Drum. In I Danced with Mrs. Gandhi, he is already employed at Drum when the trip occurs, and the delay precipitates the fight with its owner that leads Stein to quit: an issue went to bed without him when the storm held him up, and the owner spiked the cover photograph of a black American tennis champion kissing her white runner-up on the cheek, which Stein had chosen to be deliberately provocative. That was the crisis that forced him to leave in protest. Between the two texts, the memory floats dislodged from its rightful place, its legs also up in the air.

In 1957, after three years at Drum’s helm, with boycotts and treason trials roiling his native country, Stein left for good on a Royal Mail steamer bound for Southampton. In I Danced with Mrs. Gandhi, he wrote that police approached the ship as it weighed anchor and he entertained the thought that they might be coming for him—for unpaid parking tickets. In the earlier book, he presented that whimsy as fact in another show of memory’s prankster ways: parking police ran up the gangplank as the siren hooted farewell and made him sign a warrant before allowing him to sail into self-exile.

Stein was the first to leave South Africa, but he certainly wasn’t the last. The address without a country—62 Regent’s Park Road—was the house in Primrose Hill where other former Drum staffers, apartheid’s refugees, regularly began to appear in the late 1950s and early 1960s. They arrived missing the township jazz that “helped to pump the blood round the heart” and finding the “English way of life punishing, penalizing, and oppressing,” he wrote in Who Killed Mr. Drum?. Many settled in the basement apartments of posh Georgian houses in the neighborhood, home to a literary set including Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. In the early years, the expats participated in this milieu and enjoyed some early professional success. Matshikiza’s musical about a heavyweight boxer from the townships, King Kong, was produced in the West End in 1961 with Miriam Makeba as star. The marquis publishing house Faber & Faber released Stein’s novels in quick succession, one each year from 1958 to 1960.

The first, written and set in South Africa, came out shortly after Stein’s arrival in London and was a Book Society pick. Second-Class Taxi tells the story of Staffnurse, a dispossessed black man who fears arrest because he lacks a pass to be in Johannesburg. The novel pokes fun at him as a credulous bumpkin who falls in with an ANC-like group of great souls, who also happen to be great scamps, campaigning for the franchise and equality for black South Africans. Stein skewers every character, including Staffnurse’s boss, a liberal white parliamentarian who officially opposes the hard-liners yet holds racist attitudes. Within days of its UK publication, Second-Class Taxi was banned and pulled from shelves in South Africa. It took a quarter century for it to be available there again.

His other novels—Old Letch, a madcap satire about British leftists, and What the World Owes Me by Mary Bowes, the bildungsroman of a fatherless girl raised in South Africa—were rhythmic with onomatopoeia, snappy dialogue, and jazzy slang and peopled by the angry young men (and women) of the moment. The Times Literary Supplement characterized Stein’s humor as “halfway between a poet’s and a clown’s.” He played with form, experimenting with metafiction before such exemplars of the genre as John Barth, John Fowles, and Doris Lessing did so. Stein’s time as one of Faber’s “bright young men,” as Sarah described it, did not last long. By the mid-1960s, creative stagnation had set in, with depression in its wake.

Other Drum comrades, forced into exile by apartheid and unable to assimilate, found themselves similarly adrift in doldrums. If Stein stumbled—his way in Britain eased by an English wife, white skin, and connections—their footing was even less sure. One Stein hire, William Modisane, floundered after initial success in London in the 1960s as the author of the memoir Blame Me on History and as a stage and film actor. Modisane wound up drinking himself to death in Germany in 1986. Themba did the same back in 1968, in Swaziland. And another key hire by Stein, Nat Nakasa, the legendary reporter in whose name a prestigious South African award for journalistic courage is now given, jumped from a Manhattan skyscraper in 1965. South Africa had granted him a visa to attend Harvard as a Nieman fellow but barred him from returning, leaving him despondent in New York at the fellowship’s end. Stein counted Nakasa as one of apartheid’s casualties, along with the magazine itself. Drum was ultimately sold—“a corpse to its executioners” in his phrase—to an Afrikaans press closely tied to the segregationist regime.

Stein watched from afar as Sophiatown was razed and one after another of the former Drum staff died before his time. Long after leaving South Africa, he remained involved in its politics, secretly raising funds for the ANC and, as a world champion sprinter late in life and founder of the magazine Running, urging an Olympic boycott of South Africa in the 1980s. In 1983, David Philip Publishers seized on a slight relaxation of censorship to reissue Second-Class Taxi and several other books banned in South Africa. This led to some renewed attention there, while Stein, who by then made his living as the publisher of tax and property newsletters and athletic publications, continued to grow old fairly quietly in London.

The deaths of his Drum comrades haunted him. Four decades after his shining moment in literary London, the Mayibuye Centre at the University of the Western Cape—which is devoted to recovering neglected aspects of South African history—published Who Killed Mr. Drum?. Although Stein frames it as a whodunit about the unsolved murder of Nxumalo, who was stabbed in an alley on New Year’s Day 1957, the book explores how all of his colleagues met their premature ends. It reads like a series of epitaphs to all those who died too young, many of them because of alcohol-related accidents or diseases while in exile.

As for his own epitaph, Stein was self-deprecating. During our last meeting, he told me, “I don’t expect I’ll be remembered very much.”

Second-Class Taxi, arguably his best and most significant book, isn’t taught or much read in South Africa today. Ivan Vladislavić, the distinguished writer from Johannesburg, believes the ban prevented it from finding an audience. That Stein quit South Africa hurt its prospects, too. During the long years of boycott and isolation, his countrymen didn’t embrace authors who had fled. The novel also may have suffered for the very quality that distinguished it: its satirical tone, rare in South African fiction when it was reprinted. “Second-Class Taxi was reissued just as South Africa entered a particularly violent and unfunny era, and I can imagine that its humor was not to everyone’s liking,” Vladislavić explained by email. If remembered, it is as a footnote, one example of political censorship among many.

If Stein had receded for South Africans, the country never really receded for him. Sixty years after he left it, it persisted as an elongated shadow across the span of his life. During an epic party he threw in Primrose Hill in the 1960s, Stein was buoyed by the company of his fellow exiles and the hilarious, liquor-lubricated tales they told about apartheid and their vanished Johannesburg. These men and women without a country had found a kind of temporary shelter in remembering together at 62 Regent’s Park Road. “Inyani! (In truth.) It could have been Sophiatown,” declared Stein, nostalgically evoking the party three decades later in Who Killed Mr. Drum?. “Home sweet home reborn.”