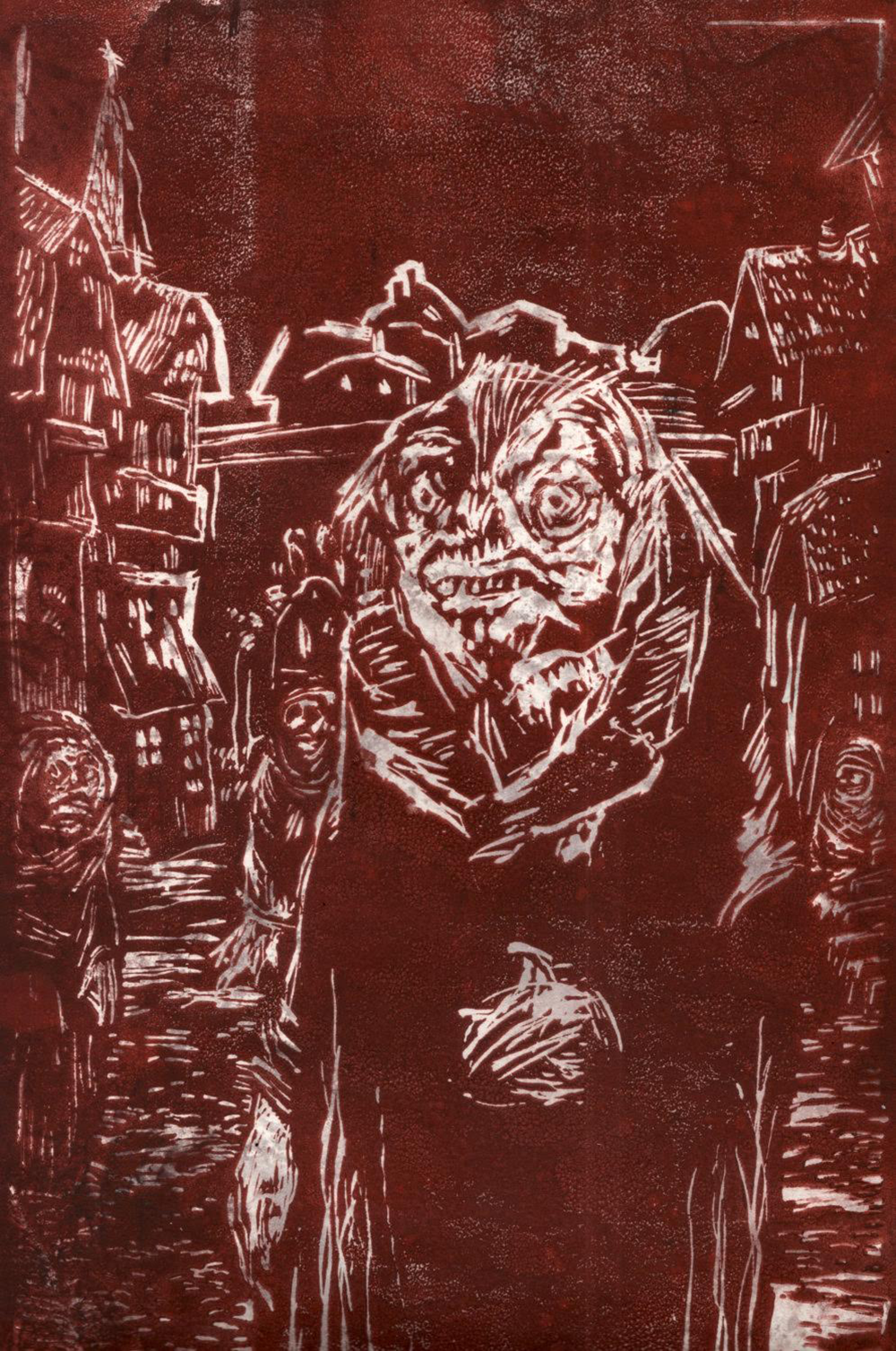

“The people of Innsmouth are not very friendly to outsiders,” by David Gassaway, 2011. Polymer clay, india ink.

“There are my ‘Poe’ pieces and my ‘Dunsany’ pieces,” H.P. Lovecraft wrote to a friend in 1929, “but alas—where are any Lovecraft pieces?” By the average standards of authorial self-criticism, Lovecraft was considered something of an extreme case. He would hold some of his stories, including those especially prized by fans today, from publication for years, and he was invariably disappointed with those he did see through to publication. Despite his wistful question, by then Lovecraft had already written many of his “Lovecraft pieces”—“The Colour Out of Space,” “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and one of his few novels, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, which he shelved for being “a creaking bit of self-conscious antiquarianism”—with more to follow. The more nagging problem was that they were not widely read, and that would not improve until after his death in 1937.

Lovecraft satisfies the great artistic creation myth that also befell contemporary outsiders like Franz Kafka and Nathanael West: falling in life only to rise in death, and all before reaching age fifty. Yet here, too, Lovecraft is an exceptional case. It is one thing to be critically canonized (both West’s and Lovecraft’s entire bodies of work—which are, admittedly, not extensive—have been published by the Library of America) and aesthetically codified (the adjectives Kafkaesque and Lovecraftian are dropped when no other words are able to capture something punishingly absurd or vividly horrifying); it is another to inspire something close to obsession in the annals of popular culture. Nor is Lovecraft’s presence limited to film adaptations and literary homages, though both are pervasive.

The arc of Lovecraft’s work over the past decades is both improbable and problematic. Casual consumers of his fiction find cathartic humor in the strangeness and bleakness of his creations, while dedicated readers are compelled by his imagination, portraying unearthly otherness with a singularly intense foreboding, but repelled by the elements that sparked it, chiefly an unshakable racism. Lovecraft at every level is an author more confronted than read—a peculiar and not altogether complimentary approach to one of the least avoidable authors of horror in recent memory.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft was born in 1890 in Providence, Rhode Island. When he died there forty-six years later, his headstone bore the epitaph “I Am Providence.” His love for his home city seems to have been matched by the unhappiness that dominated his experience of it. Lovecraft’s father, Winfield, a traveling salesman, died before his only child was ten, after being institutionalized for a syphilis-related mental breakdown. He was close with his mother, Sarah Susan Phillips, later writing that she “was, in all probability, the only person who thoroughly understood me.” But the traumas of her husband’s death and increasing financial insecurity cast dual shadows over the mother–son relationship. The two were largely reclusive for much of Lovecraft’s upbringing, and she would sometimes comment that her son’s face was “hideous.” In 1921, when Lovecraft was thirty, his mother died while institutionalized after a nervous breakdown.

A gifted child, Lovecraft was speaking by age one, reading by age three, and writing by age six, but he was not without his own maladies. It is believed that he was plagued by sleep paralysis and night terrors for much of his childhood. Frequent illnesses, some “probably nervous in origin,” according to critic and Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi, often kept him out of primary school, and he dropped out of high school after three years. Despite his intelligence, his academic output was inconsistent. The bulk of his immense learning was acquired on his own. He had a flair for science, producing multiple hectographed journals on the topic, starting with The Scientific Gazette, written when he was nine. An ambition to study astronomy at Brown was derailed by his lack of proficiency in mathematics, however.

Lovecraft’s literary interests were stoked by his maternal grandfather, industrialist Whipple Van Buren Phillips, who had amassed an extensive library where Lovecraft read Grimms’ fairy tales and The Arabian Nights before discovering Poe when he was eight. His grandfather regaled him with stories of the gothic and weird, a foundation on which he laid the sturdier work of authors across genres: the fantasies of Lord Dunsany and Arthur Machen, the ghost stories of Algernon Blackwood and M.R. James, and the macabre visions of Ambrose Bierce and Edgar Allan Poe.

Lovecraft’s entry into fiction writing conveniently coincided with the rise of pulp magazines, cheaply produced publications dedicated to salacious, tawdry, and formulaic but compelling genre fiction. It was an outlet with which he had a conflicted relationship. Though the magazines connected him with a small circle of admirers, they did not pay well, and the editors’ handling of his work sometimes infuriated him. Nor was he an ideal stylistic fit. His first contribution to a pulp magazine was a letter to the editors of Argosy attacking the hackish work of romance writer Fred Jackson. Jackson is forgotten now, but Lovecraft’s invective sparked a yearlong conflict with other readers, escalating into exchanges of satirical verse. It also paved a way for him to make his own contributions to the same magazine.

The problem with Lovecraft is that one does have to read him. Pulp fiction has always been a minefield of execrable prose, but Lovecraft elevates it to a high anti-art. At its most typical, Lovecraft’s work combines serpentine sentences, dry exposition, arcane vocabulary with pretentious British spelling, and questionable narrative devices. One representative passage conjures a grandiloquent phantasmagoria:

The aperture was black with a darkness almost material. That tenebrousness was indeed a positive quality; for it obscured such parts of the inner walls as ought to have been revealed, and actually burst forth like smoke from its aeon-long imprisonment, visibly darkening the sun as it slunk away into the shrunken and gibbous sky on flapping membraneous wings. The odour rising from the newly opened depths was intolerable…Everyone listened, and everyone was listening still when It lumbered slobberingly into sight and gropingly squeezed Its gelatinous green immensity through the black doorway into the tainted outside air of that poison city of madness.

Such elaborate convolutions make Lovecraft an easy and frequent target for parody. Among the earliest was Arthur C. Clarke’s 1940 story “At the Mountains of Murkiness,” which reads like something out of Mad magazine: “Surely, I thought, the mad Arab, Abdul Hashish, must have had such a spot in mind when he wrote of the hellish valley of Oopadoop in that frightful book the forbidden Pentechnicon.” The satirical website Clickhole gets even more in the spirit of things, describing an “off the chain” party at Lovecraft’s with “an undulating mass of celebs, Old Ones, studio bigwigs, and still viler beings whom I dare not consider, stretching indefinitely in all directions.”

More arcane than Lovecraft’s style are the mechanics of his storytelling. He relied almost entirely on first-person narration, often provided by the protagonist retelling his descent into madness in implausibly painstaking detail. Often in place of dialogue are long secondhand exegeses that tell rather than show. Lovecraft confessed his aversion to writing about “ordinary people,” and he consistently relied on the archetype of a cold, sexless, and cerebral man as the main character, a solitary academic so bereft of both interior and exterior life that he jitterbugs along the razor’s edge of total abstraction. It is easier to think of his protagonists as verbal wind-up toys subjected to whatever universal unknowns his stories throw at them. “The only ‘heroes’ I can write about,” Lovecraft wrote, “are phenomena.”

If there is one distinguishing feature of Lovecraft’s characters, it is a dogged inquisitiveness that never fails to undo them in the end. A banner example can be found in “The Call of Cthulhu.” A straitlaced Bostonian discovers a sculpture “of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature” among his great-uncle’s academic papers, sending him down a wormhole. His journey takes him across continents; dream visions, cult rituals, and encounters at sea all become tied to Lovecraft’s now iconic beast Cthulhu. “I have looked upon all that the universe has to hold of horror,” the narrator laments, “and even the skies of spring and the flowers of summer must ever afterward be poison to me.”

“The Call of Cthulhu” was not among Lovecraft’s favorite works—“middling,” he called it, but “not as bad as the worst”—and he had to submit it twice before Weird Tales accepted it. Yet the story was revered by his peers. Writing to Weird Tales, Robert E. Howard declared the story “a masterpiece, which I am sure will live as one of the highest achievements of literature.”

Howard was one of Lovecraft’s closest friends and most frequent correspondents. Like Lovecraft, he could be pigeonholed as a troubled misfit with mommy issues; he too died young but not before leaving behind an iconic creation, Conan the Barbarian. Yet there the comparisons end. Unlike Lovecraft, Howard was a gripping stylist and a natural, vigorous storyteller who honed his art by reciting his stories aloud as he typed them. Unapologetically virile, erotic, and violent, they fit Weird Tales’ visual aesthetic, and the screen adaptations entranced filmgoers. Howard was an entertainer, as were the majority of the writers who published in pulp; though more than mere hacks, they dwelled in Lovecraft’s shadow. Howard recognized the difference and wrote, “Mr. Lovecraft holds a unique position in the literary world; he has grasped, to all intents, the worlds outside our paltry ken. His scope is unlimited, and his range is cosmic.”

“All my tales are based on the fundamental human premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the cosmos-at-large,” Lovecraft wrote in 1927. “To achieve the essence of real externality…one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all.” His continual pursuit of knowledge—particularly regarding what Joshi called the “remarkable convergence of scientific advance in the course of the nineteenth century that systematically destroyed many previously unassailable pillars of religious thought” in his book The Unbelievers: The Evolution of Modern Atheism—took him away from his WASP heritage (his mother was Baptist, his father Anglican) and into mechanistic materialism: “In theory I am an agnostic, but pending any rational evidence I must be classed…as an atheist. The chance of theism’s truth being to my mind so microscopically small, I would be a pedant and a hypocrite to call myself anything else.” Though discoveries such as Einstein’s theory of relativity and quantum mechanics left him traumatized, he found a way to reconcile them that harmonized with his vision of the world: “The absence of matter or any other detectable energy-form indicate not the presence of spirit, but the absence of anything whatever.”

Therein you have what makes up “cosmic horror,” a term far more suitable for Lovecraft’s work than the usual “weird fiction” label. It is the bleakest vein of horror, in which innumerable imaginative avenues lead to the same destination: humanity’s revelation of its universal insignificance. “For Lovecraft, human beings are too feeble to shape a coherent view of the universe,” writes the philosopher John Gray. “Our minds are specks tossed about in the cosmic melee; though we look for secure foundations, we live in perpetual free fall.”

Lovecraft’s cosmic horror saw humanity not as the center of an intricate universe but as an aberration, pathologically error-prone. In stories including “Chtulhu,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and “The Whisperer in Darkness,” they willfully conjure extraterrestrial beings to absolutely no one’s benefit. “It might be best to recall how we treat ‘inferior intelligences’ such as rabbits and frogs,” wrote Michel Houellebecq in his book on Lovecraft. “In the best of cases they serve as food for us; sometimes…we kill them for the sheer pleasure of killing. This, Lovecraft warned, would be the true picture of our future relationship to those other intelligent beings.”

In this sense, “The Call of Cthulhu” reads more as a philosophical document, even a manifesto. The opening sentence—“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents”—does for cosmic horror what Breton’s “so strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life…that in the end this belief is lost” did for surrealism or even what Marx and Engels’ “a specter is haunting Europe” did for communism. Only instead of pledging to liberate humanity, cosmic horror puts it in its place.

In the conservative religious journal First Things in 2009 David P. Goldman wrote:

Among all the film genres horror began as the most alien to America…As Heinrich Heine once observed, the witches and kobolds and poltergeister of German folktales are remnants of the old Teutonic nature-religion that went underground with the advent of Christianity. The pagan sees nature as arbitrary and cruel, and the monsters that breed in the pagan imagination personify this cruelty. Removed from their pagan roots and transplanted to America, they became comic rather than uncanny. America was the land of new beginnings and happy endings. The monsters didn’t belong.

Lovecraft agreed. Dying from cancer in 1937, never able to make a living off his writing and admired largely only by other genre writers, he was convinced his stories would fade into obscurity, the same fate eventually met by all the other pulp hacks. Eight years later, Edmund Wilson exhumed his work only to tear it down: “The only real horror in most of these fictions,” Wilson wrote in The New Yorker, “is the horror of bad taste and bad art.” Yet Lovecraft’s work has not just persevered but thrived, and because of rather than in spite of the bleak view it espouses. But appreciating this achievement means reckoning at the same time with its darker underpinnings, which reinforce his legacy as much as it scandalizes.

Lovecraft’s admirers have long had to come to terms with his views on race. In one moment he could spin pseudo-scientific racialism: “Of the complete biological inferiority of the negro there can be no question—he has anatomical features consistently varying from those of other stocks, and always in the direction of the lower primates.” In another he could veer into murderous hate: “The white minority [in the south] adopt desperate and ingenious means to preserve their Caucasian integrity—resorting to extra-legal measures such as lynching and intimidation when the legal machinery does not sufficiently protect them.” Joshi and other admirers admit the ugliness of Lovecraft’s views while claiming they do little to detract from his work. The problem is that his racial fixations inform his writing; they are not discrete concerns. Nowhere is this more evident than in “The Horror at Red Hook,” which depicts New York as “a hopeless tangle and enigma; Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and Negro elements impinging upon one another,” the city teeming with “illegal immigrants…nameless and unclassified Asian dregs wisely turned back by Ellis Island.” The cultists in “The Call of Cthulhu” are “very low, mixed-blooded, and mentally aberrant.” “The Rats in the Walls” notoriously costars a cat named “Nigger Man.” The titular town in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” is populated by citizens with “queer narrow heads with flat noses and bulgy, starry eyes that never seem to shut” and possess the “fish blood” of a sea-dwelling amphibian-like race of “Old Ones.”

Lovecraft’s racial views are not only ugly and strident but also deeply contradictory. In his stories humanity is an unhappy accident in the universe, acting with no rhyme or reason; the same goes for the more powerful beings they encounter. Yet at the same time he also argued for a hyper-rational race-based hierarchy of humanity. “No anthropologist of standing insists on the uniformly advanced evolution of the Nordic as compared with that of other Caucasian and Mongolian races,” he wrote in a 1931 letter:

As a matter of fact, it is freely conceded that the Mediterranean race turns out a higher percentage of the aesthetically sensitive and that the Semitic groups excel in sharp, precise intellectation. It may be, too, that the Mongolian excels in aesthetick capacity and normality of philosophical adjustment. What, then, is the secret of pro-Nordicism among those who hold these views? Simply this—that ours is a Nordic culture, and that the roots of that culture are so inextricably tangled in the national standards, perspectives, traditions, memories, instincts, peculiarities, and physical aspects of the Nordic stream that no other influences are fitted to mingle in our fabric.

This pseudointellectual framework did not carry very far into reality, however. Lovecraft’s wife, Sonia Greene, recalled that on their walks in New York he would be “livid with rage” at the sight of the city’s racially mixed population: “He seemed to almost lose his mind.” Such visceral reactions poured back into his work, tainting it with racist bile. “Racial hatred,” wrote Houellebecq, “provokes in Lovecraft the trancelike poetic state in which he outdoes himself by the mad rhythmic pulse of cursed sentences.”

Lovecraft’s wild mystical racism coexisted in his fiction with his atheism, which was as unforgiving as it was logical. Though rooted in the rational triumph of science over the spiritual and in the assurance that beliefs in God, the soul, and the soul’s immortality were “clearly traced to delusive conditions, fears, and wishes of primitive life,” it offered none of the redemptive faith the New Atheists found in scientific progress. His works were steeped in fear and delusion, and their atheism turned out a synthesis of the bleak diagnoses of Schopenhauer—who saw existence as futile and humanity driven by irrational reflexes—and Nietzsche—who eulogized God and told humanity it had to do something about it. Lovecraft, then, saw humanity searching for any and all manner of deity in a vast, chaotic chasm and finding only indifferent leviathans.

It would seem ironic, then, that so unbelieving an author would also be considered the creator of the Cthulhu mythos, the overarching vision thought to arise out of Lovecraft’s literary canon. Encompassing all of his extraterrestrial creations, along with some outside additions, both the term and the concept came not from Lovecraft but from his fellow writer, correspondent, and admirer August Derleth, who assumed the Max Brod role of collecting and publishing his works in book form for the first time after Lovecraft died. Arkham House, the publishing company he cofounded in 1939 to bring out Lovecraft’s works, still exists, and continues to publish its own editions of Lovecraft as well as books by and related to Lovecraft’s pulp contemporaries Clark Ashton Smith, E. Hoffmann Price, Hugh B. Cave, and others.

Derleth is controversial among Lovecraftians. Though he has done more than anyone else to save Lovecraft from an otherwise assured oblivion, his authorial dalliances with Lovecraft’s ideas have been much less appreciated. Joshi found that Derleth propagated “numerous errors, distortions, and outright lies about Lovecraft’s fiction and general philosophy,” and Derleth’s creation and expansion of the Cthulhu mythos “widely depart from Lovecraft’s conceptions” and “are pretty awful in their own right.” Derleth’s mythos story “Ithaqua,” for instance, borrows more from the Wendigo legend than from Lovecraft’s cosmos. Derleth, moreover, was a Christian, and his mythos is cast—however willfully or haphazardly—in a decidedly moral light, with benevolent “Elder Gods” who “imprison” the malevolent “Old Ones” on earth. “The Cthulhu mythos is analogous to the Christian mythos,” Joshi wrote, “especially in regard to the expulsion of Satan and his minions from heaven.”

Still, the impact of Derleth’s heresies was limited by the lack of rigidity necessary to enforce his interpretation of Lovecraft’s creations. Other authors from Stephen King to Colin Wilson and Philip José Farmer have paid their own tributes in mythos-themed anthologies. The Cthulhu mythos has become less of a literary project than one of the highest classes of fan fiction ever conceived, offering a universal vision that fits more comfortably into a fantasy roleplaying game than a literary school. Derleth’s mythos speaks to a fan-driven impulse to contribute to a creator’s ideas rather than to understand them—not that Lovecraft was wholly averse to such enthusiasm. “It would be truer to say that Lovecraft encouraged some of his writer friends to include references to his inventions in their work, and he reciprocated,” author Ramsey Campbell wrote in a Reddit thread on the mythos:

It was conceived as an antidote to conventional Victorian occultism―as an attempt to reclaim the imaginative appeal of the unknown―and is only one of many ways his tales suggest worse, or greater, than they show. Alas, after his death other writers (sadly, me included) started codifying it until it grew just as conventional as the stuff he was trying to counteract.

Horror asks us to stare in the face an act that disgusts us, that reverses our placid expectations, uproots our moral foundations, or degrades our assumed dignity. In Lovecraft, readers find a horror that is less a well-told tale and more a deeply felt sensory onslaught. He is less akin to Edgar Allan Poe than he is to the Marquis de Sade. Both wrote with aggressively dense and atmospheric styles. Both depicted worlds of violence, elaborate fantasy, and unforgiving misanthropy. Both were perverse commentators on human freedom. Freedom was a kind of madness, but that madness split in opposing directions between willful and forcible. For Sade it was the only acceptable end of human striving; for Lovecraft it was the inevitable end of human folly. Sade’s humanity is depraved, its freedom bottomless; Lovecraft’s humanity is contingent, its freedom cavernous. In “The Colour Out of Space,” Lovecraft wrote:

This was no breath from the skies whose motions and dimensions our astronomers measure or deem too vast to measure. It was just a colour out of space—a frightful messenger from unformed realms of infinity beyond all Nature as we know it; from realms whose mere existence stuns the brain and numbs us with the black extra-cosmic gulfs it throws open before our frenzied eyes.