Gentlemen:

It may not have escaped your professional observation that there are only two classes of mankind in the world—doctors and patients. I have some delicacy in confessing that I belong to the patient class—ever since a doctor told me that all patients were phenomenal liars where their own symptoms were concerned. If I dared to take advantage of this magnificent opportunity which now lies before me, I should like to talk to you all about my symptoms. However, I have been ordered—on medical advice—not to talk about patients, but doctors. Speaking then, as a patient, I should say that the average patient looks upon the average doctor very much as the noncombatant looks upon the troops fighting on his behalf. The more trained men there are between his dearly beloved body and the enemy, he thinks, the better.

I have had the good fortune this afternoon of meeting a number of trained men who, in due time, will be drafted into your permanently mobilized army which is always in action, always under fire against Death. Of course it is a little unfortunate that Death, as the senior practitioner, is always bound to win in the long run, but we noncombatants, we patients, console ourselves with the idea that it will be your business to make the best terms you can with Death on our behalf; to see how his attacks can best be delayed or diverted, and when he insists on driving the attack home, to take care that he does it according to the rules of civilized warfare. Every sane human being is agreed that this long-drawn fight for time which we call Life is one of the most important things in the world. It follows therefore that you, who control and oversee this fight and you who will reinforce it, must be among the most important people in the world. Certainly the world will treat you on that basis. It has long ago decided that you have no working hours that anybody is bound to respect, and nothing except extreme bodily illness will excuse you in its eyes from refusing to help a man who thinks he may need your help at any hour of the day or night. Nobody will care whether you are in your bed or in your bath, on your holiday or at the theater. If any one of the children of men has a pain or a hurt in him you will be summoned. And, as you know, what little vitality you may have accumulated in your leisure will be dragged out of you again.

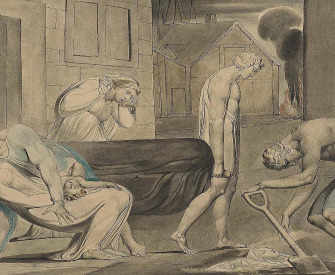

Achilles binding Patroclus’ wounds, from a kylix by the Sosias Painter, c. 500 BC. Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany.

In all times of flood, fire, famine, plague, pestilence, battle, murder, or sudden death, it will be required of you that you report for duty at once, go on duty at once, and remain on duty until your strength fails you or your conscience relieves you, whichever may be the longer period. This is your position. These are some of your obligations. I do not think they will grow any lighter. Have you heard of any legislation to limit your output? Have you heard of any bill for an eight-hour day for doctors? Do you know of any change in public opinion which will allow you not to attend a patient even when you know that the man never means to pay you? Have you heard any outcry against those people who are perfectly able to pay for medical attention and surgical appliances, and yet cadge round the hospitals for free advice, a cork leg, or a glass eye? I am afraid you have not.

To do us poor patients justice, we do not often dispute doctors’ orders unless we are frightened or upset by a long continuance of epidemic diseases. In that case, if we are uncivilized, we say that you have poisoned the drinking water for your own purpose, and we turn out and throw stones at you in the street. If we are civilized, we do something else. But a civilized people can throw stones too. You have been and always will be exposed to the contempt of the gifted amateur—the gentleman who knows by intuition everything that it has taken you years to learn. You have been exposed—you always will be exposed—to the attacks of those persons who consider their own undisciplined emotions more important than the world’s most bitter agonies—the people who would limit and cripple and hamper research because they fear research may be accompanied by a little pain and suffering.

You remain now perhaps the only class that dares to tell the world that we can get no more out of a machine than we put into it; that if the fathers have eaten forbidden fruit the children’s teeth are very liable to be affected. Your training shows you daily and directly that things are what they are and that their consequences will be what they will be—and that we deceive no one but ourselves when we pretend otherwise. Better still you can prove what you have learned. If a patient chooses to disregard your warnings, you have not to wait for a generation to convince him. You know you will be called in in a few days or weeks, and you will find your careless friend with a pain in his inside, or a sore place on his body, precisely as you warned him would be the case. Have you ever considered what a tremendous privilege that is? At a time when few things are called by their right names, when it is against the spirit of the times even to hint that an act may entail consequences—you are going to join a profession in which you will be paid for telling men the truth, and every departure you may make from the truth you will make as a concession to man’s bodily weakness, and not his mental weakness.

Realizing these things, as I have had good reason to realize them, I do not think I need stretch your patience by talking to you about the high ideals and the lofty ethics of a profession which exacts from its followers the largest responsibility and the highest death rate—for its practitioners—of any profession in the world. If you will let me, I will wish you in your future what all men desire—enough work to do, and strength enough to do your work.

From a speech delivered to the students of the medical school of Middlesex Hospital. Poet, short-story writer, and novelist, Kipling for four years in the 1890s lived in his wife’s hometown in Vermont, where he learned the art of the “small things … buying yeast cakes and being lectured by your neighbors.” Of the general opinion that only “lesser breeds” are born outside of England, he returned to the seat of the British Empire and published Captains Courageous in 1897 and Kim in 1901.

Back to Issue