Luck is believing you’re lucky.

—William Carlos Williams, 1947

The Finding of Moses, by Paolo Veronese, c. 1580. © Gianni Dagli Orti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

It is not difficult to be wise occasionally and by chance,

but it is difficult to be wise assiduously and by choice.—Joseph Joubert

The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins posts the odds on the chance encounter and then fertile union of sperm and egg in my mother’s womb at a number outnumbering the sand grains of Arabia. Long odds, but longer still because “the lottery starts before we are conceived. Your parents had to meet, and the conception of each was as improbable as your own.” Work back the thread of lucky breaks through all the antecedents animal, vegetable, and mineral that are the sum of mankind’s time on earth, and wherefrom consciousness and pulse if not at the hand of the bountiful blind woman, Dame Fortune?

The incalculable run of luck I’m unable to comprehend as a number; I hear it as a sound. Thirty-five years ago in a labor room at New York Hospital, the sonogram of my wife’s belly picking up the heartbeat of my youngest child on final approach to the light of the sun. He’d come a long way. Atoms wandering in the abyss, then in the womb for the nine months during which a human embryo ascends through a sequence touching on over 3 billion years of evolutionary change, up from the shore of a prehistoric sea, traveling as amphibian, fish, bird, reptile, lettuce leaf, and mammal to a room with a view of the Queensboro Bridge. I heard the sound then, hear it now, as the chance at a lifetime shaped from the dust of a star.

Albert Einstein didn’t wish to believe that God “plays dice with the world,” but the equations posted on the blackboards of twentieth-century physics—among them Einstein’s own proof of wave-particle duality, Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, Max Planck’s quantum mechanics—suggest that chance is a force of nature as fundamental as gravity. So does the consensus of opinion in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. Except for sixteenth-century theologian John Calvin, who believed there is no such thing as fortune and chance, that “all events are governed by the secret counsel of God,” the witnesses called to testify on the pages that follow regard Dame Fortune as a presence to be reckoned with, visible to the eye of history, glimpsed across the bridges of memory and metaphor in the words of the occasionally wise.

The Broken Mirror, by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, c. 1762. © Wallace Collection, London / Bridgeman Images.

Heisenberg conceived of all facts as momentary perceptions of probability; so did Titus Lucretius Carus, the Roman poet who in the first century BC composed the 7,400 lines of lyric but unrhymed verse On the Nature of Things infused with the thought of Greek philosopher Epicurus, who in the third century BC taught that the universe consists of atoms and void and nothing else. No afterlife, no divine retribution or reward, nothing other than a vast turmoil of creation and destruction, the elementary particles of matter (“the celestial seeds of things”) constantly in motion, colliding and combining in the inexhaustible wonder of everything that exists—sun and moon, the wind and the rain, “bright wheat and lush trees, and the human race, and the species of beasts.”

Thomas Jefferson, when asked for the source of his philosophy, identified himself as “an Epicurean,” listing On the Nature of Things among the books from which he never ceased learning. He borrowed from it in 1826 to petition the Virginia state legislature for permission to dispose by lottery enough of his property at Monticello to settle a $100,000 debt. The legislature twice denied permission on the ground that games of chance are immoral. Jefferson had posed the question:

But what is chance? Nothing happens in this world without a cause. If we know the cause, we do not call it chance; but if we do not know it, we say it was produced by chance…If we consider games of chance immoral, then every pursuit of human industry is immoral; for there is not a single one that is not subject to chance, not one wherein you do not risk a loss for the chance of some gain.

The legislature reconsidered its decision, but before a lottery could be held Jefferson died bankrupt, his family forced to sell the property at a price favoring the buyers. One man’s gain, another man’s loss, but no moral in the tale because reality makes itself up as it goes along, a near infinite number of atoms encountering one another at unstable moments in time, made temporarily manifest as bank balance, bonobo, or butterfly. If physics is nature and nature is God (three worknames for the same tradecraft), God is free to throw dice with cause and effect because all the skin in the game is his own.

E.M. Cioran, Romanian philosopher, writing in 1969, finds in the comfort of pagan wisdom an escape from the dungeons of Christian theology. If “there is no misfortune that we cannot refer as we like either to a distraction of Providence or to the indifference of Chance, or finally to the inflexibility of Fate,” we shake free of “the morbid optimism which, despite all the evidence, identifies progress with apotheosis.” The ancient philosophies found the best chance to lead a sweet life and generate offspring in the embrace of beauty and the pursuit of pleasure—pleasure not as sensual debauchery but as the sense of well-being embodied in living justly and lovingly in a generosity of spirit.

Christianity repositioned pleasure as sin, the meaning of life as pain, its enjoyments placed in escrow for redemption in heaven. A bait and switch, says Cioran, because if the celestial seeds of things are eternal, the time in being is all the time there is, was, ever will be. A nonexistent future can “add nothing essential to the existing data” and therefore loses currency as “an object of horror or hope.” No day of judgment, no pit of hell, no communist utopia or capitalist paradise. The notion fits with the letter of condolence Einstein wrote in 1955 to the sister of his friend Michele Besso: “Michele has left this strange world a little before me. This means nothing. People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction made between past, present, and future is nothing more than a persistent, stubborn illusion.”

The nineteenth-century philosopher

Arthur Schopenhauer borrows the wisdom of antiquity to name “sagacity, strength, and luck” as the three great powers in the world. He likens a man’s life to the voyage of a ship, luck acting “the part of the wind” that “speeds the vessel on its way or drives it far out of its course.” Going on to say that men owe whatever merit they possess to the “goodness and grace” of the bountiful blind woman, he concludes that the course of a man’s life

is in no way entirely of his own making; it is the product of two factors—the series of things that happened, and his own resolves in regard to them, and these two are constantly interacting upon and modifying each other.

The observation accords with the theories of wave-particle duality and quantum mechanics. Also with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. On the Origin of Species is subtitled “The Preservation of Favored Races,” the argument of the book employing the term natural selection to indicate the absence of intention or design, which, to say it more plainly, is the presence of luck. The favored races are those that bend the gifts of nature in the direction of what circumstances show to be their best interests.

At the age of eighty-one I still can’t say whether the vessel of my life is on or off course, but I do know that its design was none of my own doing. Born in San Francisco of sound mind and body to loving parents in a neighborhood under the protection of money, I understood before I was ten that I’d been dealt favorable cards; I also knew that the playing of them was another game of chance. The realization I count as a stroke of fortune (the happiest of the lot) because when and if I can bear it in mind it allows me to live in the freedom of the present and hold at bay the fear of death.

Looking for a how or where or why I came up with the idea, I see my grandfather at a card table constituted as he was in 1943, a Falstaffian figure then in his sixties, white-haired, round-bellied, and boisterous, fond of quoting the wise fools in Shakespeare’s forests. A captain of infantry in World War I, Roger D. Lapham had gone missing in the battle of Château-Thierry, after five days given up for lost and presumed dead, his family so notified and his personal effects shipped home to New York. Six weeks later he was found in a barn drinking calvados with the French peasant who had dragged him, unconscious and half-buried in mud, from the womb of a shell hole. Grandfather’s leg being broken, he was unable to walk, but he had emerged from the shadow of the valley of death believing it was better to be lucky than good. Before the war he conducted himself in the manner of a sober, self-denying Calvinist; he returned from France as a practicing pagan, reckless in pursuit of pleasure, ardent in his passion for gambling. At the bridge table he liked to bid his hand without looking at his cards, and between the ages of eight and ten I was often drawn into the game as his partner because nobody else in the family would play with him unless favorably situated as his opponent. His trusting to luck the family deemed immoral; I thought it deserved a medal.

Another of my early influences, Mr. Charles Mulholland, a robust and high-hearted Irishman, I see standing at a blackboard armed with a fistful of chalk. My grammar-school history teacher, he incorporated Homer’s Odyssey (vessel wandering before winds loosed by game-playing Greek gods) into the long course of military history, ancient and modern, that he spread out across grades five through eight from the walls of Troy to the wheat field at Gettysburg. Luck figured prominently in his after-action reports of battles won and lost, and, like my grandfather given to broad and theatrical gesture, Mr. Mulholland often interrupted his telling of stories to mock the scholarship that repositioned the study of history as science. He didn’t hold with epistemologies that identified “scientific progress” (social, political, economic, and aesthetic) as a steadily onward and upward advance toward earthbound apotheosis. The way of knowing—sicklied o’er with the pale cast of morbid optimism—he thought better suited to the tending of machines than to an understanding of the human predicament, unstable and subject to the rollings of dice.

Grandfather taught by example, Mr. Mulholland by precept, but as to where else I came by my childhood respect for Dame Fortune I can only guess at probabilities—surviving two bicycle accidents that should have proved fatal, not being touched by the illnesses that afflicted my brother, my mother reading to me at age seven Melville’s story of Moby Dick—Ahab bound to the whiteness of the whale in a twist of rope and fate, Ishmael risen on a coffin from the depths of the sea.

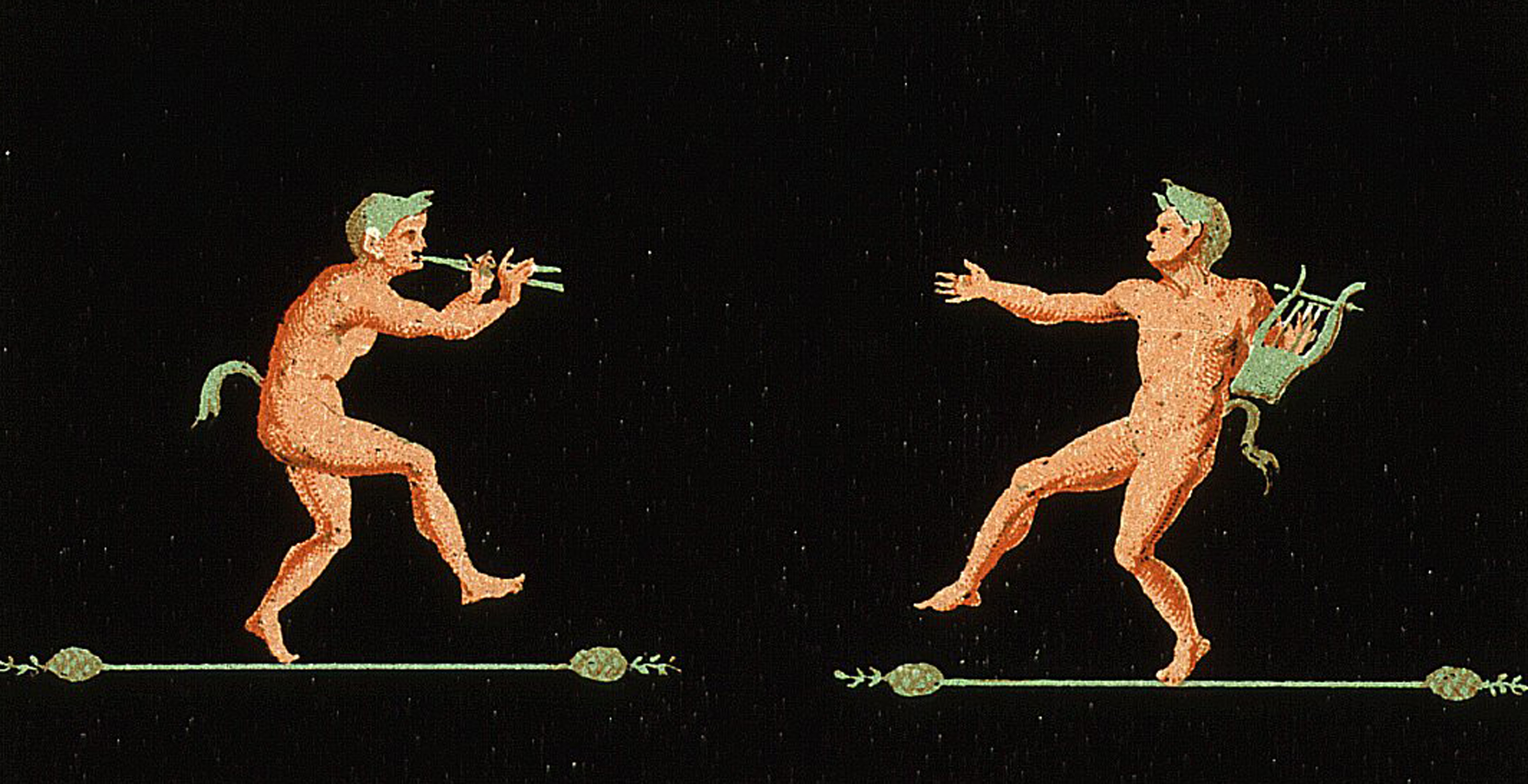

Tightrope walkers, reproduction of a Pompeian fresco from Houses and Monuments of Pompeii, by Fausto and Felice Niccolini, c. 1890. © Gianni Dagli Orti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

At prep school in northwestern Connecticut I spent entire afternoons on the bank of the Housatonic River gazing at the movement of clouds, of fish and ants and willow trees, seeing them at the varying distances of two inches, twenty feet, and 200 million years. My sense of an enormous wonder-working present interfered with my seeking to get ahead in the world. Get where? Ahead of whom or of what, if we’re all in the same boat at the same time?

Neither my father nor Yale College provided maps charting the voyage of a life or a career, and I wasn’t much good at making plans for the day after tomorrow, much less for a midterm examination. I pursued the course of my undergraduate reading for the pleasure in it and of it, with little or no thought of a grade point average. My grandfather’s passion was gambling, mine proved to be learning. Books I looked to as numbers in a lottery. I bet the favorites touted by the faculty, chased long shots on tips from students studying astronomy and Buddhist philosophy, played hunches gleaned from a footnote or bibliography. The cause for the effect I stumbled upon in sophomore year in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King. The novel in an early chapter locates the wizard Merlyn on a riverbank like the one in Connecticut, talking to young Arthur not about the choice of a career but about the hedge against misfortune. “You may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics,” and the best you can do is to “learn why the world wags and what wags it.” Learning “is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

So I have found it to be as both reader and writer. I never know what I know about anything until I frame it in a sentence, fish it into the net of a metaphor, never sure what the words mean until they show up as momentary probabilities on a page. Their appearance, reality making itself up as it goes along, is more a matter of luck than of conscious design.

“Our brains,” says Schopenhauer, “are not the wisest part of us.” A man deciding on an important step at the great moments of his life is “directed not so much by any clear knowledge of the right thing to do as by an inner impulse…proceeding from the deepest foundations of his being.” I don’t doubt him, but neither do I doubt the theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli, whose Seven Brief Lessons on Physics locates the deepest foundations of my being in a cloud of unknowing:

We have 100 billion neurons in our brains, as many as there are stars in a galaxy, with an even more astronomical number of links and potential combinations through which they can interact…“We” are the process formed by this entire intricacy, not just by the little of it of which we are conscious.

Combine the testimony of philosopher and physicist, and how else to regard my selection of sentence, occupation, and wife except as the trusting to luck? I left college for journalism on the chance of learning why the world wags and what wags it, and was impressed by the great number of stories that hinged, as did Mr. Mulholland’s battles, on a turn of good or bad luck.

So have the lives of every man, woman, and child I’ve come to know well enough over the last sixty years to hear tell of their travels on the roads from a once upon a time to a who knows where. I don’t think I’ve ever met anybody who didn’t set out in one direction to end up in another, happened to be sitting in row B instead of row A when the names were called for promotion or prizes, moved on impulse to a change of address, encountered by chance the chance of a lifetime.

Nor is it surprising that Americans are a species devoted to gambling, into the pit of which passion they poured at least $120 billion in 2013. The existence of America in the first instance is the gift of Dame Fortune, the celestial seeds of things colliding and combining in ways deemed by Richard Dawkins, “all but perfect for our kind of life: not too warm and not too cold, basking in kindly sunshine, softly watered; a gently spinning, green and gold harvest festival of a planet.”

We do not suffer by accident.

—Jane Austen, 1813Secondly, the bountiful wilderness that fell to the lot of the first settlers arriving in seventeenth-century New England possessed of the good grace to know it was none of their doing. Thirdly, their immunity against diseases imported from the Old World that killed off inhabitants of the new. Fourthly, the wealth of learning that is the record of what men on their travels across the frontiers of the millennia have found to be useful or beautiful or true—the spoils of the seventeenth-century scientific revolution and the eighteenth-century Enlightenment of Scotland and France offloaded onto the wharves of Philadelphia and Boston together with Seneca’s letters and Newton’s mathematics; the Chinese inventions of gunpowder, the compass, and the printed word; the writings of Machiavelli and Voltaire. America’s Founding Fathers exploited the natural resource of history as diligently as their descendants exploited the lands and forests of the Ohio River Valley and Trans-Mississippi frontier, well aware, as was E.M. Cioran, that the historical process oscillates “between determinism and contingency, accident and law, physics and fortune.”

The scientific notions of historical inevitability assume the existence of implacable abstractions (economic, social, and political) moving like tectonic plates far below the surface of the news. They propose a story with no people in it. The course of events is always contingent, reality making itself up as it goes along (sometimes merrily, more often not), and as likely to turn on the accidents of human character and personality as on the shifts in a market or the weather. If a heavy fog doesn’t drift into New York Harbor on the morning of August 30, 1776, George Washington’s retreating army, trapped by the British in Brooklyn Heights, doesn’t make good on its escape in rowboats across the East River to Manhattan; if that army doesn’t survive, neither does the American Revolution. Nor does the revolution succeed without the assistance of France, which wasn’t a gift from Adam Smith’s invisible hand. The Treaty of Alliance followed from the particular quality of Benjamin Franklin’s intelligence that allowed him to persuade an absolute monarch to bankrupt his kingdom in order to finance a democratic rebellion.

The State Lottery, by Vincent van Gogh, 1882. © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam / Bridgeman Images.

The signers of the Declaration of Independence staked it as a bet, placing “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor” under the protection of divine Providence without looking at their cards. The British Empire in 1776 was the world’s presiding superpower. The Americans invited war with no weapons in their hands—no army, no stores of shot and shell, no money to pay for uniforms or cannon.

The Constitution doesn’t come with a moral in the tale, doesn’t hold the liberties of the people in escrow for redemption on earth or in heaven. Relying on the pagan wisdoms of Cicero and Plato, the composers of the document established the American idea as an existential one, allowing the fragments of energy and light lucky enough to have been assembled under its star every chance in the deck to catch the train or miss the boat. Construed as a means and not as an end, the Constitution serves as the start-up of a story, not as the plan for an invasion or a monument, and not just one story but many stories, all of them in need of a lucky break (usually at least three or four) and more than a little help from one’s friends. None of them come outfitted with a guarantee that hard work and good behavior provides a decent living and a happy ending. The morbid optimism is what the preachers and politicians sell for a living, but I never know why anybody believes their sales pitch. Most stories end in failure and loss (Jefferson died bankrupt, as did Tom Paine and Herman Melville), but the assigning of misfortune to chance relieves the burden of self-hatred. Instead of finding fatal flaws in my unknown being, I can take comfort in the wisdom of Tom o’ Bedlam in King Lear:

To be worst,

The lowest and most dejected thing of fortune,

Stands still in esperance, lives not in fear.

The lamentable change is from the best;

The worst returns to laughter.